Читать книгу L'Americain - John Launois - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

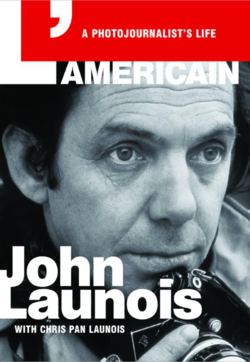

Prologue PROLOGUE CHRIS PAN LAUNOIS

ОглавлениеL’ Américain is the story of my father, John Launois, an impossible man with a beautiful heart. For most of his life, my father was far away from me, either on assignment or living abroad, but he’d call often to stay connected, exchange perspectives, or simply to say, “I miss you. I love you.” On my repeated visits to him in Europe, he’d recount stories of his life with the humor and gravity of a passionate adventurer who had followed his dreams and lived to tell the tale.

As a poor boy in France, he faced a childhood that could have been imagined by Dickens. He once cut off the leather straps of his mother’s whips to stop her from using them on his younger brothers and sisters. She constantly told him he was worthless: “You’ll never amount to anything.”

World War II brought the worst of times. Poverty for the least privileged of the French during Nazi occupation became life threatening, and John’s father feared that his children, even if they survived, would never be free. Oppression fueled John’s rebellious nature: as he defied the Germans at every turn and listened to clandestine broadcasts about the approaching liberation by U.S.-led Allied forces, the boy fell in love with America.

When free-spirited GIs finally arrived, personifying a democratic society so different from his class-ridden homeland, John was already such an enthusiast for all things American that his friends called him L’Américain.

Soon he had developed a grand vision of his future. Idealizing the land of his dreams, he vowed to turn himself into a “Yank” and work for Life, the greatest of the picture magazines. With nothing but $50 and a borrowed camera, he crossed the Atlantic. In time, after working a series of menial jobs in California and learning photographic skills, he would cross the Pacific as well.

John finally gained his citizenship while serving as a U.S. Army soldier, then struggled through his “noodle years” of low-paying photographic tasks before advancing to the highest ranks of international photojournalism during its “golden age.”

Freelancing for Life, The Saturday Evening Post, National Geographic and many other leading publications, he traveled to the ends of the earth—always enterprising, creative, and fearless in a risky profession.

He covered wars, riots, and natural disasters; mingled with the rich, famous, and powerful as well as the downtrodden; and always marveled that he had come so far from the lower depths.

John was the picture of the globetrotting adventurer—photographing conceptual essays around the world, interviewing presidents, befriending the Beatles and revolutionaries like Malcolm X.

Ultimately, John was a Romantic who loved, lost, and loved again. His two greatest loves—my Japanese mother and my Austrian stepmother—became close friends upon his death. The three of us, drawn together by our affection for such a passionate, contradictory man, had urged him on as he devoted himself to telling the story of his life.

For seven years, my father and I worked on his manuscript. Sometimes it flowed easily; often the task was challenging. He persevered because he felt he owed a debt to the nation that had liberated France and shared her liberty at home. Alongisde so many other brave hopefuls who dared to carve out a better destiny, his name is proudly engraved on Ellis Island.

He once promised a dear friend that he would write this book. It’s a memoir of a rebel and adventurous man. To keep a promise, this is the story of L’Américain.