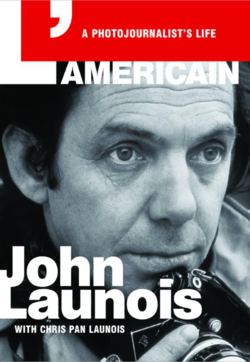

Читать книгу L'Americain - John Launois - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction INTRODUCTION DONALD S. CONNERY

ОглавлениеThe first American he ever saw fell out of the sky.

In 1943, John Launois was Jean René Launois, a rebellious, high-spirited, 14-year-old, who lived with his working-class family in a town near Paris in Nazi-occupied France. World War II was the terrible reality of his childhood: nearly five hard years of hunger, deprivation, oppression, and national humiliation.

One day, the boy watched as the crew of a B-17 Flying Fortress bailed out after being struck by antiaircraft fire. A parachute “wrapped around itself and one young airman fell straight to earth,” as John tells us in this book. He raced to the scene but the Germans had already removed the corpse. “Engraved in the soft grass was the imprint of a body.”

Ashamed of his country for collaborating with Hitler, the schoolboy despised the autocratic, class-ridden society determined to stifle his chances for a better life and marveled that a faraway country—the United States of America—would send its youth across the ocean to save France.

“I wanted to know more, but all things American were banned. In my mind, I began to create a mythical America. I told so many tales, real and imaginary, that soon my nickname became L’Américain.”

The youngster fantasized about going to the USA. He would shed his European skin and become one of the free and the brave. He would Americanize himself so completely that no one, not even his own family, would ever again think of him as anything but American.

He succeeded in this transformation far beyond his wildest dreams.

Before the ascendancy of television as the prime purveyor of images, Life, Look, Paris Match and the other great picture magazines in America and Europe captured world events for readers who numbered in the tens of millions. During the 1960s and 1970s, the final decades of the “golden age of photojournalism” that had begun in the 1930s, John Launois blossomed as one of the most resourceful, inventive, prolific, highly paid, and widely traveled of the elite corps of press correspondents and cameramen sent to the ends of the earth to record history in the making.

John made himself the master of the deeply researched photo essay and always clung to his independence, selling his pictures and photo essays through New York’s Black Star agency, with his published work appearing for over a quarter century in Life, the Post, National Geographic, Fortune, Time, Newsweek, Look, Rolling Stone, Paris Match, London’s Sunday Times, and many other American, European, and Asian publications.

I was Time-Life’s Tokyo bureau chief in 1960–1962, and before going on to Moscow to cover the Cuban Missile Crisis for Time Inc. and NBC, I worked with John soon after his emergence from poverty and obscurity. In the perilous Cold War summer of 1961, we teamed up for a month-long, round-the-world journalistic coup that propelled him to the top rank of his profession.

It was John—with typical initiative and cunning, his Gallic charm melting the frozen-faced Russian diplomats in Japan—who wheedled a way for us to do the seemingly impossible. Despite the ongoing Berlin Wall crisis that threatened to touch off World War III, we quietly entered the Soviet Union through its Far Eastern back door and rode the Trans-Siberian Railway 6,000 miles to Moscow.

At stops along the way, always under surveillance (and several times accused of being CIA spies), we recorded everyday life in cities and villages and on collective farms that had been closed to Western observers since the end of World War II.

Our editors expected the Trans-Siberian Railway, the world’s longest, to be the centerpiece of our story, but as our journey began, the Soviets said it was out of bounds for security reasons. We were forbidden to take pictures “of the train, on the train, or from the train.” As John explains in one chapter, we found ways to break the rules. Miraculously, considering the risks we took, we avoided arrest and flew away to Paris and New York with all of our film and notes intact.

That world scoop, told in a black-and-white spread in Life and in a lavish color section in Time, was promoted as “Two Yanks in Siberia.” For John, being certified as an American—a Yank!—by the world’s most powerful publishing company was fully as satisfying as his sudden new status as a top-gun photojournalist.

After Siberia, I could only keep track of him by reading the magazines that benefited from his workaholic ways. He seemed to be everywhere: from London with the Beatles, to Cairo with Malcolm X, to the jungles of the Phillipines with a lost Stone Age tribe.

With the passage of years, I found myself ever more fascinated by the makeover of the thin, ill-dressed, insecure, yet fiercely ambitious young man I had first met in Japan. The slight stoop of his nearly six feet, I later surmised, had been acquired as a boy hauling heavy sacks of potatoes for a grocer. His earnest hazel eyes, shaggy auburn hair, and his eagerness to get moving on a story gave him an aura of unstoppable purpose. He was more winsome than handsome. The longing and sadness of his expression—perhaps the result of his mother’s taunts that he would never amount to anything—aroused the maternal instinct of female admirers.

As John’s accent faded away, I came to think of him as “the un-Frenchman.” He smoked filtered American cigarettes instead of the stronger Gauloise or Gitane of his native land. He preferred Scotch over wine, and in ample quantities. He made no great fuss about food. He was more of an American prude, putting women on pedestals, than an all-knowing French lover. Nonetheless, he always had a sympathetic ear. In Kyoto for a Life cover story on actress Shirley MacLaine dolled up as a geisha, I observed John’s way of attracting the most intimate of confidences from new friends, as his look-alike, French actor Yves Montand, poured out to him his woes of romantic entanglements.

In the field, John wore the usual safari garb of his calling, but as success brought sophistication, his style of dress at home was strictly Ivy League. He was the life of any party, a convivial host, and the inevitable center of attention as he spoke of exotic lands that most people could only dream about. Yet his mood could shift in a week’s time from elation about a job well done to a desperate need to get back into action.

In time, as the mass-circulation picture magazines died off one by one, John found no satisfaction in corporate assignments or “just taking pretty pictures.” Always the photojournalist, believing in the power of images to expose, inspire, and help make a more humane world, he could not stomach being less a journalist and more a photographer.

At the turn of the century, John told me he was working on his autobiography. He would, of course, tell of his often perilous experiences as a globetrotting photojournalist, but uppermost in his mind was his unquenchable love affair with America.

As a self-described “American idealist,” he was forever loyal to the land of his childhood imaginings despite endless disappointments. As I knew from his frequent late-night transatlantic calls, he took personally every lapse of moral leadership in Washington, every display of military arrogance, every sign of hypocrisy by political leaders ignoring social injustice, and every departure from his vision of America’s destiny as the shining city on a hill.

I encouraged him to tell his story. The world should know him as a modern Horatio Alger—a striving, idealistic, romantic immigrant who was more American in his sensibilities than most native-born Americans.

As a freelancer who carried out demanding tasks for a wide spectrum of publications, John enjoyed maximum creative freedom, but it had come at a price. He was such a loner that he never became a celebrity. He did not benefit from the Life and Look practice of promoting their star staff photographers. Even so, editors recognized him as the consummate professional. On one occasion, Fortune advised its readers that pictures by John Launois, the “indefatigable and far-ranging freelancer,” could be found in four stories on four different subjects in that single issue.

I told John that there was value in his account of a photojournalist’s life in that demanding era before satellites, personal computers, digital cameras. and phones that now flood the world with instant images. Today’s amateur photographers can transmit pictures in seconds to anyone anywhere on earth, while yesterday’s crack photojournalists often found that getting exposed film shipped to the home office by mule or a military flight could be the most challenging part of the job.

What I did not anticipate in John’s manuscript was the naked honesty of his personal story. He exposes the demons that clawed at his mind. He is ruthless in blaming himself and his blinding drive to excel for so often distancing himself from his loved ones.

John virtually invites readers to dissect him psychologically as he lays out his contradictions. “An impossible man,” according to his son, he was intense, impulsive, generous, self-centered, compassionate, endearing, and infuriating.

John died at 73 in May 2002, his manuscript nearly finished.

Had I known then what I know now, reading his story, I would have told him not to be so hard on himself. He was cherished by those who knew him best. This book has reached publication only because of their devotion and their desire to see that his life as a good man as well as a vastly talented man be more widely recognized.

The dedication to John’s memory demonstrated by his first wife Yukiko in New York and his widow Sigrid in Liechtenstein has been critical to this work. His son, Chris Pan Launois, a Manhattan-based musician and song writer, helped create the manuscript, working on its completion as his father’s eyesight faded in the years before his heart stopped.

For all three, it has been a labor of love.