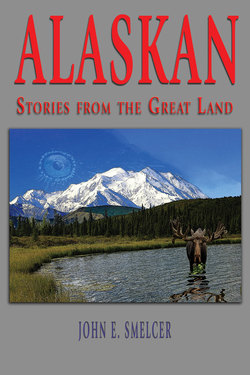

Читать книгу Alaskan: Stories From the Great Land - John Smelcer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Pond

George Joseph plunged through the ice when he reached for the exhausted dog, which tried frantically to climb onto the man’s head to keep from drowning, the front paws scratching the man’s face and scalp. George grabbed hold of the dog and held him close to his chest, keeping the animal’s head above water. At first the dog struggled but then relaxed.

“It’s alright boy,” said the man, feeling the dog’s deep trembling. “I’ve got you.”

The man and his dog had been on their daily walk along the shoulder of the road when the dog ran down the hill toward a frozen pond after a rabbit.

“Heel boy! Heel! C’mere!” he had shouted, whistling and clapping his hands.

But halfway across, the heedless dog had crashed through the thin ice. No matter how many times the dog tried to pull himself out, the edge broke away.

George had run down the hill, found a long branch under a tree, and with it had shuffled over the ice toward the dog. The ice moaned when he crept close to the middle, so George got down on his hands and knees and crawled as far as he dared go, holding out the branch, encouraging the dog to bite hold of it so he could pull him out.

“Grab on, Boy! Come on!” he shouted.

But the frightened dog didn’t understand. Every minute, he became weaker and weaker, until even the dog understood that his feeble attempts to climb out became futile. He was so tired and his muscles so cold that he could barely keep his head above the surface.

But George wouldn’t give up.

He had bought the dog as a puppy for his daughter’s sixth birthday. Tabitha carried the squirming little puppy all day long, hugging and kissing it. She named him Sam. The girl and dog were inseparable. He followed her everywhere, escorting her each morning to the end of the driveway to catch the school bus, carrying her sack lunch in his mouth. He was always waiting at the same place when the bus returned in the afternoon. At night, he always slept curled up at the foot of her bed.

By the time Sam was three years old, he out-weighed the girl by a good ten to twenty pounds.

One summer day, Tabby was riding her bicycle along the edge of the road with the dog trotting in a field beside her smelling everything, when a blue van came speeding over a blind hill, swerving across the center line into the oncoming lane and then back again, the tires kicking up rocks and dust when they hit the gravel shoulder.

The police report said Tabby died instantly from the impact. It also said she was thrown thirty-seven feet and that when the police arrived on the scene the two men, Thomas Two Fists and Victor Crow were sitting in the truck with the doors closed, while the dog stood over the wreckage of the girl, protecting her, licking her face, whimpering and whining and occasionally nudging her with his black nose.

The police had contacted George and his wife from the address on the dog’s tag.

Two Fists, who was driving, was sentenced to five years in prison for involuntary manslaughter. It should have been a lot longer, but although police could smell alcohol on his breath, they couldn’t get the breathalyzer to work properly. As a result, the inconsistent blood-alcohol level readings were thrown out. Thomas was released after serving only three years.

George had heard that Two Fists was back in town and that he had beat up his wife for seeing other men while he was in prison. But she was too afraid to report the abuse, so she just moved away one night—just packed a little bag and left with some man she had met at the diner where she worked as a waitress.

She left like a take-out order.

The first year after Tabby’s death, George and his wife shuffled from room to room as if haunting one of those old boarded-up houses with white sheets draped over all the furniture, dust settling on the silence. They were two ghosts occupying the same empty space, each unable to see the other. And like a ghost, one day the apparition that had been his wife simply vanished.

But Sam remained, with the needs of the living. George mechanically remembered to feed the dog, to provide water, and periodically to let him out to do his business. But he didn’t pet him or talk to him or play fetch with him like he used to. Sometimes the dog only sensed that the man was in the same room, the way they say dogs can sense the lonely spirits of the dead.

A year or two after his wife left, George began to breathe again, to gain solid form until he was able to move things. He stopped sitting in Tabby’s room for hours weeping and praying that everything could be like it used to be. Everything in the room had been left the way it was the day she died, a ten-by-twelve-foot museum to grief and guilt. George’s vanished wife hadn’t taken a single thing from the room.

A van, a slow-moving blue van, drove by on the road above the pond, then stopped for a moment before backing up. Two men stepped out from the idling vehicle. Even from that distance George recognized them. Two Fists ran down the hill without a jacket. Victor followed, carrying a coiled rope over his shoulder.

Both men stood at the edge of the pond.

“We’re coming to get you, George!” shouted Two Fists.

“Hold on, George!” shouted Victor.

Quickly, Victor tied the long rope around Two Fists’ waist, leaving about thirty feet of rope in Two Fists’ grip, more than enough to reach George and the dog. While Victor stood safely on dry ground firmly holding one end of the rope, Two Fists shuffled out across the ice toward the struggling man and dog, holding the loose rope in his hands as he moved.

“Hang in there, George, I’m almost to you,” he kept saying.

When he was as close as he dared go—the ice threatening to break beneath his feet—Two Fists slung the coiled end of the rope toward George. It continued to unwind as it slid across the pond’s frozen surface, its long end splashing into the icy water within easy reach.

“Grab on!” he yelled. “You can do it!”

Still holding Sam against his chest, George grabbed the rope, gripped it as tightly as his cold hand would permit.

Two Fists pulled in the slack and began to back up, each step finding thicker ice. Digging his heals into the firm crust of snow-covered ground, Victor pulled in the slack between them. Together, they pulled George and his dog from the water, the way Eskimos pull a walrus or a whale from the icy sea. They kept the tension until George was able to get to his feet and stumble to shore, still gripping the rope. Sam walked beside him, shuddering.

“Shit, Man,” said Two Fists to George when he was safely off the pond. “You’re freezing. Let’s get you to my van and take you home.”

The two Indians helped George up the hill and into the warm van. Two Fists climbed into the driver’s seat, turned up the heater to full blast, and drove down the road.

Victor stayed in the back of the van helping George.

“I gotta get you out of these soaking-wet clothes,” he said, as he carefully removed George’s coat and red flannel shirt. “Here, Man, put this on,” he said, placing his own jacket around George and then patting him on the shoulder. “You’re gonna be alright.”

Sam lay on the floor shivering and licking ice from between his paws.

“Hey, George,” said Two Fists, turning his head just enough to see the freezing man behind him, “sure is lucky for you that we was driving by, eh?”

Victor agreed. “Yeah, Man, you sure are one lucky dude. Another minute and you’d have been dead.”

George nodded. He could smell alcohol on their breath.

When they arrived at the house, Two Fists led George to the bathroom and started a hot shower for him. He helped him take off his boots and socks while Victor made a pot of coffee and dried Sam with a towel he found hanging in the kitchen.

“Hey, George,” said Two Fists before he closed the bathroom door, “don’t forget to put something on those scratches when you’re done. Damn dog got your face pretty good.”

The two men sat in the kitchen drinking coffee laced with shots of whiskey from Victor’s flask until George finally came out wearing a bathrobe and warm house slippers.

“I want thank you guys,” he said, pulling out a chair and sitting at the table.

Two Fists poured a cup of coffee and slid it toward the man.

“Drink up, George. It’ll warm up your insides.”

George drank from the hot cup, holding it with both hands, warming them.

No one said a word after that. It was so quiet that the ticking clock on the wall filled the room.

“Listen George,” said Two Fists after a while. “I’m sorry about what happened, Man. You know, about your kid and all. It was an accident. Maybe we’re even now, eh?”

“Yeah, Man,” said Victor nodding in agreement, “we’re real sorry about what happened. We didn’t even see her until it was too late. Shit happens, you know?”

George stared into his cup, rubbed a thumb along the rim. He didn’t breathe until the clock’s ticking again filled the room.

“Did you hear us, George?” said Two Fists, placing a hand on George’s arm. “We said we was sorry.”

“I’m tired,” said George without looking up. “I think I’ll take a nap.”

The two men stood, gathering up their coats from behind the chairs.

“That’s a good idea, George. You get some rest,” said Victor. “We gotta get going anyhow.”

Two Fists turned before he closed the door.

“Remember, George,” he said. “We’re even now.”

He closed the door, and a moment later George could hear the sound of snow crunching beneath tires as the van backed into the road and drove away. He sat at the kitchen table. After a while, he got up and walked into his daughter’s room. He sat on her bed holding a picture that was taken on her sixth birthday. In the photograph, Tabby is holding the puppy against her chest, while George and his wife are kneeling beside her with their arms around her. Everyone is smiling.

Sam ambled in, his nails clicking on the wood floor, and plopped down on the hook rug with a sigh.

George knelt beside the dog and petted him. He wrapped his arms around the dog’s neck and held his head close to his own, weeping for all he had lost. He wept for the long-abandoned bird nest that was his heart.

The dog occasionally licked the man’s face.

Later, as the sun began to set, George got up, wiped his face, dressed, and put on a dry coat, boots, and a hat. He called to the dog, still sleeping on the floor.

“Come on, Boy. Let’s go for a ride.”

The dog followed him outside and, when George opened the creaking door, jumped into the truck. At ten ripe years, jumping up onto the bench seat was getting harder and harder for Sam.

George drove to the pond with Sam sitting on the seat beside him, watching the white world pass by. The night was clear, and the moon shone with a hard-edged clarity, casting shadows. When they arrived, George parked along the edge of the road, near to where the blue van had pulled over. Although it was dark, he could see the footprints leading out to the pond, see them vanish at the thinly-frozen place where he and Sam had fallen through. For several minutes he sat in the warm truck and stared at the scarred surface of the pond. He was struck by how the recently formed ice gave the appearance of something solid, solid enough to bear a man’s weight. He laid a gentle hand on Sam’s head. The dog turned and looked into the man’s eyes.

George climbed out and let the dog jump down. He reached behind the seat and pulled out his rifle, checked to make sure it was loaded.

“Let’s go for a walk, Boy,” he said, without looking at the dog.

Eagerly, the dog trotted toward the pond, occasionally turning around to make sure he had not lost the man.