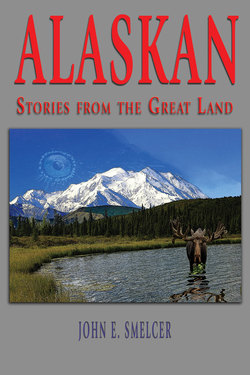

Читать книгу Alaskan: Stories From the Great Land - John Smelcer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction to Alaskan

This selection of stories represents almost thirty years of writing. Ronald Reagan was president when some of these stories first made their way onto paper. For me, the storytelling process began in the early-to-mid 1980s, when I was an undergraduate student majoring in anthropology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (my mother might say it began in the early ‘70s when I used to sit and write stories, some of which she kept). At the time, James Michener was prowling the university’s Rasmussen Library, researching for a historical nonfiction book about Alaska. Michener had a stark little office in the English Department, and I used to walk past it every day. Eventually, we struck up a conversation. For the rest of his residency, we spoke almost daily and lunched together often in the Wood Center, the university’s cavernous student union building. It was during those lunches that we brainstormed the title for his book-in-progress. I vaguely remember that one alternative we had discussed was “Russian America.” Michener eventually settled on ALASKA.

Michener became keenly interested in the Alaska Native side of my family. Spurred by his interest, I began to write some of the myths I had heard all my life, especially from my grandmother and uncle. I also wrote a couple of short stories based loosely on my own experiences in the wilds of Alaska. I’d sit impatiently on the floor outside his office while he read them. When he was finished, he offered generous feedback. By the end of our friendship, I had compiled a pretty good collection of myths. Michener asked the great mythologist Joseph Campbell to look them over. Both eventually leant their names to the project—Campbell writing a foreword and Michener a back cover blurb. The book, The Raven and the Totem, has now been through numerous re-printings and translations and is being expanded into a second edition.

But I’ve strayed from the history of the stories in this collection. Before he left Fairbanks, Michener encouraged me to add English as a second major and to keep writing fiction. That decision changed the trajectory of my life. Before that, I was going to spend my career as an officer in the U. S. Army, like my father. And although Michener had a good things to say about my short stories, I never felt as confident about them as he did. For the most part, I became a secret short story writer, rarely sending them out to magazines or journals. I was less unsure of my poems, sending them out in droves by wheelbarrow. Many years later, I took some of my best short stories and expanded them into my first novels. To the casual observer, it must seem that I went straight from poetry to the novel, but that’s not really the case. I spent years struggling with story and character. I still do.

In the decades since Michener encouraged me to write, some of America’s greatest writers have touched these stories. For instance, in 1999, John Updike arranged for me to meet J. D. Salinger in his hometown of Cornish, New Hampshire. Updike and I had served together as co-judges of the National Poetry Book Award in the mid 1990s. We met Jerry in town at a popular restaurant, downstairs of an historic bed and breakfast. While waiting for our guest, I was editing a spiral-bound, photocopied manuscript containing many of the stories that would eventually end up in this collection, which has had many tentative titles over the years, including River’s Edge and Darkness and a couple more I can no longer recall. When Salinger walked in, I put away the manuscript. During lunch, Salinger asked what it was I had been working on when he arrived. Updike complimented the stories enough so that Salinger asked to see them. After reading the first story at the table—while I fidgeted nervously and chewed off my fingernails—he asked if he could keep the bound manuscript, promising to make comments and to return it to me in a week or two. In my blithering attempt to seem grateful, I insisted he accept five bucks for mailing costs and wrote my address on the cover. Sure to his word, the manuscript arrived some weeks later with his very useful suggestions, including his recommendation to trash a few stories or to start them over from scratch from a different angle. I often wonder what he thought about my boneheaded offer of five bucks. I think he volunteered because I didn’t ask him in the first place and because he was legitimately interested, not so much in me but in Alaska.

Maybe he loved Jack London’s stories as a boy.

Others writers who played an important role in the creation of these stories include my friends James Welch and my one-time moose hunting partner Michael Dorris—two writers intimately familiar with the contemporary Native American experience.

Many of my stories are autobiographical. For instance, “The Awakening” is based on a caribou hunting trip where I witnessed firsthand the instant of a young shaman’s spiritual awakening. Chief Harry Johns was the grandfather-chief in the story. “River’s Edge” and “The White Hills of Denali” happened to me pretty much exactly as told. “Crash” happened on the Cassier Highway on my way home to Alaska. Believe it or not, “The Mammoth Eaters” is also autobiographical. During the summer of 1982, I walked every mile of the coast of the Arctic Ocean. One day, while exploring, I stumbled upon the unmistakable carcass of a woolly mammoth. Some stories are based on experiences as told to me by my Native friends or relatives. Some stories, like “The Walrus Hunters,” are drawn directly from Alaskan newspaper headlines. Most Alaskans know the incredible true stories behind “Sunday Drive” and “A Stroke Before Midnight.” Others are entirely fictional, though even they are rooted in a kind of truth about Alaska and its people. For instance, one day during the late 1980s, while searching the archives of the Rasmussen Library’s Polar Collection, I came across the journal of a Swedish expedition. Having lived in Sweden, I planned to translate the manuscript. Contained within its pages was an anecdote that eventually became the basis of “The Lost Journal of the Swedish Polar Expedition.” Annie Dillard echoes the story in her splendid The Writer’s Life. Some stories portray the danger of living in a place where winter temperatures can plummet to almost a hundred degrees below zero with a wind chill factor. One sad story is based on an interview with an elder who was taken from her village as a child and sent to a faraway boarding school in Oregon. I still have the audio-recorded interview. From 1879 until the late 1950s, Native American and Alaskan Native school-children were sent to distant boarding schools with the expectation of making them less Indian. Many of my relatives were among those taken. Finally, some lighter stories are thrown in for levity. A heart can take only so much despair.

From my decades of secret, closet writing of short stories, I learned enough of the craft to shape my first novel, The Trap, which won the James Jones Prize. The Trap received numerous national awards, including an award from the American Library Association and was named a Notable Book by The New York Public Library. My follow-up novel, The Great Death, also published worldwide, was a finalist for the William Allen White Award, one of America’s oldest and most prestigious awards for children’s literature. My third novel, Edge of Nowhere is loosely based on my own life and was named one of England’s best books of 2010. Both The Great Death and Edge of Nowhere were selected for England’s National Literacy Trust Booklist.

Still, I did very little with my short stories.

In closing, allow me these two points of advice for readers unfamiliar with Alaska’s history. First, Alaska Natives do not live on reservations like “Lower-48” Indians (there’s one exception, but that’s a different story). I would argue that, for this book, life on a reservation and life in a remote Alaska Native village are comparable: both are isolated, impoverished, and heavily subsidized by government. It’s also important to note that Alaska Native surnames are not stereotypic Indian names, such as “Red Hawk” or “Dances With Wolves.” Indeed, due to culturally insensitive practices in the past, many Alaska Natives have first names for last names, such as John George, George Johns, Walter Charley, Charley Peters, Frank Isaac, Isaac Frank, and so forth. Naturally, this isn’t always the case. Many Alaska Natives have Russian surnames for obvious historical reasons. Examples include Evanoff, Totemoff, Petrovich, and Demientieff. Early on, Western European traders callously listed in their record books the names of Alaska Natives with whom they traded by where it was they were from. For instance, an Indian from Gulkana might be called Gulkana Charley. My own surname derives from my father’s father, a German American who came to Alaska some time after the Gold Rush and eventually married my very young, full-blood Indian grandmother, Mary Joe. Her father, my great, great grandfather, was Tazlina Joe, so named because he came from Tazlina Village, where I built a rustic cabin on land given to me by my grandmother. His father, my great-great grandfather, was Old Man Lake.

All my life, I have known only the Alaska Native side of my family. I know almost nothing of my mother’s side, having only visited them once or twice for a holiday. For almost three years, I was the tribally appointed executive director of the Ahtna Heritage Foundation, a tribal nonprofit created to document and help preserve our customs, practices, and, most importantly, our language, which, with only about a dozen living speakers, is among the most endangered on earth. On a frigid day in 1999, Chief Harry Johns held a special ceremony in Copper Center to designate me a Traditional Ahtna Culture Bearer. In my lifetime, and from my travels to villages around Alaska, I have witnessed the slow erosion of Alaska Native traditional ways. Too much has been lost in this collision of cultures. The price is steep. Diabetes, obesity, domestic violence, rape, alcoholism, fetal alcohol syndrome, and suicide are among the highest rates in the United States. Part of the reason, I believe, lies in a lack of identity, in not knowing one’s place in the world or how to fit in.

And while some of the stories are beautiful celebrations of life in the North, many bear on this subject of disillusion. They are not meant to point out ugliness, failures, or fault. They are meant only as cautionary tales, as a window into our world as a wolf-fur-trimmed mirror in which we Alaskans may better see ourselves as those we have become. The scene beyond the window, as well as the reflection, can change.