Читать книгу Landscapes - John Berger - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

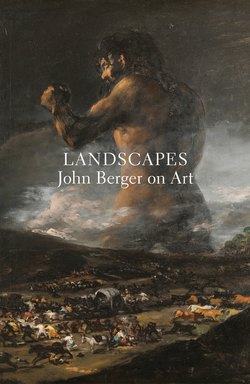

Introduction: Down with Enclosures

ОглавлениеWHAT DOES IT mean for a piece of writing to be on or about art? This book’s companion volume, Portraits, was one answer, assembling the variety of approaches John Berger has taken to individual artists. A timeline structured by dates of birth and death made space for evaluations and re-evaluations of lives and works by the light of different written forms, and changed historical and personal contexts.

Their structure meant excluding texts such as ‘The Moment of Cubism’ (1966–8), in which Berger argues that, though there might be individuals we associate with developments in art between 1907 and 1914,

Cubism cannot be explained in terms of the genius of its exponents. And this is emphasised by the fact that most of them became less profound artists when they ceased to be Cubists. Even Braque and Picasso never surpassed the work of their Cubist period: and a great deal of their later work was inferior.

This extract is about art in the sense that the author is trying to reveal what circulates and forms it – searching for the conditions from which it arises, or the climate into which it was received. Berger came to intellectual maturity in a post-war London subculture of refugees from European fascism, and the pieces of writing in which he looks beyond England and processes the thought of Brecht, Lukács, Benjamin, Frederick Antal, Max Raphael, Rosa Luxemburg and James Joyce are other omissions from Portraits.

Another aspect of the relationship between ‘The Moment of Cubism’ and art is that, by documenting a startlingly fertile period of history in which ‘there was no longer any essential discontinuity between the individual and the general’, Berger inaugurated such a period in his own work.

The essay appeared in the March–April 1967 edition of New Left Review. Later that April, it was followed by an extract in New Society from A Fortunate Man – a new book, made with the photographer Jean Mohr, which described the life of a GP in the Forest of Dean through a series of fictionalised case histories. As a work somewhere between biography and portraiture, A Fortunate Man shares an outlook with ‘No More Portraits’, the August 1967 New Society essay in which Berger announced: ‘We can no longer accept that the identity of a man can be adequately established by preserving and fixing what he looks like from a single viewpoint in one place.’

At the time, Berger was also writing G. (1972), a novel about modernism, published at the moment of postmodernism. The work turned this insight into a motif, repeated throughout the book: ‘Never again will a single story be told as though it were the only one.’

Berger repeated entire chunks of text from G. in his most famous book and TV series about art, Ways of Seeing. The title announced a pluralistic approach, and reflected the collaborative way in which it was made (with Mike Dibb, Sven Blomberg, Chris Fox and, in the episode on the male gaze, Eva Figes, Barbara Niven, Anya Bostock, Jane Kenrick and Carola Moon). At the end, part-way between soliciting disagreement and pre-empting it, Berger expressly shows the book and series to be a meeting of makers and audience: ‘I hope you will consider what I arrange, but please, be sceptical of it.’

Berger was again trying to live up to what he had identified in ‘The Moment of Cubism’: a ‘new scientific view of nature which rejected simple causality and the single permanent all-seeing viewpoint’. This struck him as an encouragement to greater self-reflexivity: ‘The Renaissance artist imitated nature. The Mannerist and Classic artist reconstructed examples from nature in order to transcend nature. The Cubist realised that his awareness of nature was part of nature.’

All the way through his writing life, Berger has written texts that take this broader, more synoptic approach to an historical period, past or present. Landscapes suggested itself as an obvious title around which to organise them. Like Portraits, it seeks sympathy with the tenor of Berger’s technique, because it is an animating, liberating metaphor rather than a rigid definition (some texts could have argued their way into either book, not least because it is so often artists who teach us how to look at art). It frees us to consider texts across genres. There are poems here as well as uncategorisable prose. And though this second volume can be read alongside the first, a landscape can be more than simply the backdrop, or ‘by-work’, of a portrait.

The word landscape is also, like many of the texts in this book, a record of the horizons of writing being broadened. The Oxford English Dictionary records various ‘landschap’ and ‘landskip’ forms being adopted from Dutch in the 1590s, before the spelling ‘landscape’ arrived in 1605. At that point, John Barrell points out,1 it was a piece of jargon specific to painting. But though Christopher Marlowe (1564–93) wrote of ‘Valleys, groves, hills and fields’ as apparently autonomous units of land, by the 1630s John Milton (1608–74) could write in ‘L’Allegro’:

Streit mine eye hath caught new pleasures

Whilst the Lantskip round it measures.

Russet Lawns, and Fallows Gray,

Where the nibling flocks do stray.

In Landscape and Memory (1995), Simon Schama argues that ‘landscapes are culture before they are nature – constructs of the imagination projected onto wood and water and rock’. The best place to explore this in Berger’s work is the discussion of Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (1727–28) in Ways of Seeing. Here, Berger made the painting pivot between the traditions of portraiture and landscape as part of a broader argument that oil painting became a dominant form because it corresponded to a certain phase of capitalism – a way of turning the visible world into tangible property. Again with an eye to plural ways of seeing, Berger packed a variety of different perspectives into this description. Kenneth Clark’s Landscape into Art (1949) provided him with a quote weighing up two of Gainsborough’s opinions on the painting of landscape, from a famous letter about ‘being sick of portraits and wishing to take his Viol de Gamba and walk off to some sweet village where he can paint landscips’ to another in which the painter writes:

Mr Gainsborough presents his humble respects to Lord Hard-wicke, and shall always think it an honour to be employed in anything for His Lordship; but with regard to real views from Nature in this country, he has never seen any place that affords a subject equal to the poorest imitations of Gaspar or Claude.

In the TV version of Ways of Seeing, the director Mike Dibb superimposed a ‘Trespassers Keep Out’ sign on the tree above the heads of Mr and Mrs Andrews, emphasising Berger’s point that the couple wanted to be painted in the land they owned because it defined their gentility. Only those with property could vote, and the poachers on their land could be deported.

Berger’s conclusions raised varied criticisms. The book incorporated the artist and art historian Lawrence Gowing’s written objections to Berger imposing himself between the ordinary art lover ‘and the visible meaning of a good picture’:

May I point out that there is evidence to confirm that Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews were doing something more with their stretch of country than merely owning it. The explicit theme of a contemporary and precisely analogous design by Francis Hayman suggests that the people in such pictures were engaged in philosophic enjoyment of ‘the great Principle … the genuine Light of uncorrupted and unperverted Nature’.

Berger’s counterargument was that one form of enjoyment does not preclude the other. If the couple are enjoying nature philosophically, they are only able to do so because they are not distracted by the possibility of being chased off it with shotguns and horse whips.

Also in 1972, the academic John Barrell published The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place. In 1980 he followed it with The Dark Side of the Landscape, in which he asked whether, when looking at the works of Gainsborough, Constable and George Morland, we ‘identify with the interests of their customers and against the poor they portray’.2

Barrell and Berger each developed their ideas on landscape through critiquing the other’s. They share some of the same motivations – Berger declared himself ‘still among other things a Marxist’ as late as 2005,3 Barrell is a ‘leftist’. But their differences become clearer in Berger’s review of The Dark Side of the Landscape, which concludes ‘Mightn’t the slogan be: Down with Enclosures! Intellectual as well as rural?’ Berger found ‘the English academic role (so dependent upon the voice and syntax)’ preserved in the book, and lamented its tendency ‘to encourage specialisation at the price of isolation’. On balance, he thought,

John Barrell’s book is a brilliant reading of certain sets of pictorial conventions (signs) and how they changed during a given historical period. But it gives little indication of knowledge, or even curiosity, about the two practices which lie, as it were, on either side of the sign. In this case the practice of painting on one side, and the practice of poor or landless peasants on the other. And so, though the book discloses and denounces an ideological practice, it contributes to and confirms the closed intermediary space in which such ideology operates.

These two practices are forms of work. Berger’s preoccupation with the work done by artists was shaped early in life. As a teenager, Berger wrote vivid short stories about the music hall and the French Resistance. But, as he describes in ‘To Take Paper, to Draw’, he went to art school (the Central and then Chelsea schools) rather than university, and, though he gave up painting around the age of thirty, his writing seems always to be accompanied by drawing. Sometimes this is purely imaginative, in much the way that say Ruskin’s or Hazlitt’s criticism is often nuanced by the experience of having made art. In the case of Berger’s Bento’s Sketchbook (2011), or ‘A Gift for Rosa Luxemburg’ (2015, collected here), the companionship of drawing is, though the term seems counterintuitive, literal: Berger’s drawings are reproduced alongside the text.

We have to be careful here not to oversimplify the relative merits of practising and non-practising critics. In ‘The Function of Criticism’, T. S. Eliot described moving from ‘the extreme position that the only critics worth reading were the critics who practised, and practised well, the art of which they wrote’ to demand for ‘a very highly developed sense of fact’ – for critics who could offer ‘interpretation’ in the sense of ‘putting the reader in possession of facts which he would otherwise have missed’. Berger’s critical dialogue with Barrell was bound up with his most sustained engagement with the idea of landscape, the Into Their Labours trilogy (1979–91).4 Through imaginative, fictional writing, these three books – Pig Earth, Once in Europa and Lilac and Flag – engage with the work of the peasants among whom he went to live in the 1970s, and whose companionship he has called ‘my university’.5 The ‘Historical Afterword’, extracted here, gives an outline of the approach to history that the trilogy takes. This is a landscape in the sense my title proposes: metaphorical perhaps, but equally alive to those who control both the appearance and the actuality of the terrain, and to those who live in it. A Fortunate Man puts it like this,

Sometimes a landscape seems to be less a setting for the life of its inhabitants than a curtain behind which their struggles, achievements and accidents take place. For those who, with the inhabitants, are behind the curtain, landmarks are no longer only geographical but also biographical and personal.

BERGER’S WORK IS an invitation to reimagine; to see in different ways. Accordingly, the texts here are divided into two parts. The first collates a range of pieces that tell us about the individuals – not necessarily visual artists – who have shaped Berger’s thought. Some – Antal, Raphael – are straightforwardly art critics; others – Brecht, Barthes, Benjamin – do not fit easily into that category, but nevertheless demonstrate how early Berger came to much of what now constitutes the expanded art-school reading list. They all play their role in shaping the self-definition as a storyteller with which, as I noted in the Introduction to Portraits, Berger frames the diversity of his written output. To consider these relationships as ones of influence would be inconsistent with this self-definition. Rather than the collective, collaborative act of storytelling, the idea of ‘influence’ seems more associated with the individualism of novel writing, and a capitalist logic of debt and restitution that Berger rejects.

The remainder of this section freely explores the limits of how writing can be about art, and the way in which Berger had been led by his painter’s eye towards storytelling. It ends with ‘The ideal critic and the fighting critic’, a kind of manifesto for how to put these examples into practice. By the end of Part I we see how, particularly in ‘Kraków’, the felt presences of Joyce, Márquez, and the tradition that now includes writers like W. G. Sebald, Arundhati Roy, Ali Smith and Rebecca Solnit have led Berger to tell the story of one of his very first teachers, his ‘passeur’, Ken, in the way that he does. The section’s title, ‘Redrawing the Maps’, originally comes from Geoff Dyer’s suggestion that ‘it is not enough simply to lobby for Berger’s name to be printed more prominently on an existing map of literary reputations; his example urges us fundamentally to alter its shape’.6

In 2012, as part of the celebration of the fortieth anniversary of Ways of Seeing and G., ‘Redrawing the Maps’ was the name given to a ‘free school’ in London that brought together an astonishingly broad range of people loosely inspired by Berger’s work to teach and learn from each other. With none of the rigidity the word might imply, Part I is a kind of syllabus, while Part II represents its application. The title of the latter is taken from one of Berger’s poems, ‘Terrain’. Here, the list of guides and maps gives way to the territory Berger uses them to navigate. Laid out in roughly chronological order, these pieces become less categorisable as they proceed, and less obviously ‘art writing’ about landscape. Yet ‘The Third Week of August 1991’ is among other things an attempt to understand the meaning of public sculpture in post-Soviet Europe. ‘Stones’ (2003) refracts contemporary Ramallah and its visual culture through some of the earliest sculpture – a cairn in Finistère. Finally, ‘Meanwhile’ (2008), the long essay that concludes the collection, defines our contemporary landscape as a prison. These pieces can be read as a sketch of art history – not that this is ever how Berger would describe his work – or as background for the individual texts of Portraits: in the sense of either the period in which they were written or the period they describe. ‘Without landmarks’, Berger writes in ‘Meanwhile’, ‘there is the great human risk of turning in circles.’

In the recent film The Seasons: Four Portraits of John Berger (2016), the actor Tilda Swinton notes that she and Berger share a birthday, 5 November (remember, remember). She reads ‘Self Portrait 1914–18’ (1970), his poem stressing how much the Great War shaped him, through his father, and the wider world into which he was born in 1926. Landscapes, then, is published to mark his ninetieth birthday. But, even alongside Portraits, it represents only a part of a much broader and still ongoing achievement – albeit one that it nourishes, and has been nourished by.

One aspect of this achievement which seems especially vital in 2016 is the great arc of Berger’s work that connects his decision to share the proceeds of his 1972 Booker Prize with the Black Panthers and his project on migrant workers, A Seventh Man (1975), through the Into Their Labours trilogy, which explored where these workers came from, and into the present via And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos (1984). There he writes,

Emigration, forced or chosen, across national frontiers or from village to metropolis, is the quintessential experience of our time. That industrialization and capitalism would require such a transport of men on an unprecedented scale and with a new kind of violence was already prophesied by the opening of the slave trade in the sixteenth century. The Western Front and the First World War with its conscripted massed armies was a later confirmation of the same practice of tearing up, assembling and concentrating in a ‘no-man’s-land’. Later, concentration camps, around the world, followed the logic of the same continuous practice.

If, as Berger writes, ‘to emigrate is always to dismantle the centre of the world, and so to move into a lost, disoriented one of fragments’, then we are all in great need of new maps.

Tom Overton, 2016