Читать книгу Landscapes - John Berger - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. To Take Paper, to Draw

ОглавлениеI SOMETIMES HAVE a dream in which I am my present age, with grown-up children and newspaper editors on the telephone, yet nevertheless have to leave and pass nine months of the year in the school where I was sent as a boy. In the dream, I think of these months as a regrettable exile, but it never occurs to me to refuse to go. In life, I ran away from that school when I was sixteen. The war was on and I went to London. Between the air-raid sirens and amid the debris of bombing I had a single idea: I wanted to draw naked women. All day long.

I was enrolled in an art school – there was not a lot of competition; nearly everyone over eighteen was in the services – and I drew in the daytime and I drew in the evenings. There was an exceptional teacher in the school at the time, an elderly painter, a refugee from fascism named Bernard Meninsky. He said very little and his breath smelt of dill pickles. On the same imperial-sized sheet of paper (paper was rationed; we had two sheets a day), beside my clumsy, unstudied, impetuous drawing, Bernard Meninsky would boldly draw a part of the model’s body in such a way as to make clearer its endlessly subtle structure and movement. After he had gone, I would spend the next ten minutes, dumbfounded, looking from his drawing to the model and vice versa.

Thus I learnt to question with my eyes the mystery of anatomy and of love, whilst outside in the night sky, I heard the RAF fighters crossing the city to intercept the German bombers before they reached the coast. The ankle of the foot on which her weight was posed was vertically under the dimple of her neck … directly vertical.

When I was in Istanbul recently, I asked my friends if they could arrange for me to meet the writer Latife Tekin. I had read a few translated extracts from two novels she had written about life in the shantytowns on the edge of the city. And the little I had read deeply impressed me with its imagination and authenticity. She herself must have been brought up in a shantytown. My friends arranged a dinner and Latife came. I do not speak Turkish, so naturally they offered to interpret. She was sitting beside me. Something made me tell my friends – no, don’t bother, we’ll manage somehow.

The two of us looked at each other with some suspicion. In another life I might have been an elderly police superintendent interrogating a pretty, shifty, fierce woman of thirty repeatedly picked up for larceny. In fact, in this our only life, we were both storytellers without a word in common. All we had were our observations, our habits of narration, our Aesopian sadness. Suspicion gave way to shyness.

I took out a notebook and did a drawing of myself as one of her readers. She drew a boat upside down to show she couldn’t draw. I turned the paper around so it was the right way up. She made a drawing to show that her drawn boats always sank. I said there were birds at the bottom of the sea. She said there was an anchor in the sky. (Like everybody else at the table we were drinking raki.) Then she told me a story about the municipal bulldozers destroying the houses built in the night on the city’s edge. I told her about an old woman who lived in a van. The more we drew, the quicker we understood. In the end we were laughing at our speed – even when the stories were monstrous or sad. She took a walnut and, dividing it in two, held it up to say: halves of the same brain! Then somebody put on some Bektasi music and all the guests began to dance.

In the summer of 1916, Picasso drew on a page of a medium-sized sketchbook the torso of a nude woman. It is neither one of his invented figures – it hasn’t enough bravura; nor is it a figure drawn from life – it hasn’t enough of the idiosyncrasy of the immediate.

The face of the woman is unrecognisable, for the head is scarcely indicated. However, the torso is a kind of face. It has a familiar expression. A face of love, become hesitant or sad. The drawing is distinct in feeling from others in the sketchbook. The other drawings play rough games with Cubist or neo-classical devices, some looking back on the previous still life period, others preparing for the Harlequin themes he would take up the following year when he did the décor for the ballet Parade. The torso of the woman is very fragile.

Usually Picasso drew with such verve and directness that every scribble reminds you of the act of drawing and of the pleasure of that act. It is this that makes his drawings insolent. Even the weeping faces of the Guernica period or the skulls he drew during the German Occupation possess an insolence. They know no servitude. The act of drawing them is triumphant.

The drawing in question is an exception. Half drawn – for Picasso didn’t continue on it for long – half woman, half vase, half seen as by Ingres, half seen as by a child, the apparition of the figure counts for far more than the act of drawing. It is she, not the draughtsman, who insists, insists by her very tentativeness.

My hunch is that in Picasso’s imagination this drawing belonged to Eva Gouel. She had died only six months earlier of tuberculosis. They had lived together – Eva and Picasso – for four years. Into his famous Cubist still lifes he has inserted and painted her name, transforming austere canvases into love letters. JOLIE EVA. Now she was dead and he was living alone. The image lies on the paper as in a memory.

This hesitant torso has come from another floor of experience, has come in the middle of a sleepless night and still retains its key to the door.

Perhaps these three stories suggest the three distinct ways in which drawings can function. There are those that study and question the visible; those that record and communicate ideas; and those done from memory. Even in front of drawings by the old masters, the distinction between the three is important, for each type survives in a different way. Each speaks in a different tense. To each we respond with a different capacity of imagination.

In the first kind of drawing (at one time such drawings were appropriately called studies), the lines on the paper are traces left behind by the artist’s gaze which is ceaselessly leaving, going out, interrogating the strangeness, the enigma, of what is before his eyes – however ordinary and everyday this may be. The sum total of the lines on the paper narrates an optical emigration by which the artist, following his own gaze, settles on the person or tree or animal or mountain being drawn. And if the drawing succeeds he stays there for ever.

In his study Abdomen and Left Leg of a Nude Man Standing in Profile, Leonardo is still there – there in the groin of the man, drawn with red chalk on a salmon-pink prepared paper, there in the hollow behind the knee, where the femoral biceps and the semi-membranous muscle separate to allow for the insertion of the twin calf muscles. And Jacques de Gheyn (who married the heiress Eva Stalpert van der Wielen, and so could give up engraving) is still there in the astounding diaphanous wings of the dragonflies he drew with black chalk and brown ink for his friends at the University of Leyden around 1600.

If one forgets circumstantial details, technical means, kinds of paper, and so on, such drawings do not date, for the act of concentrated looking, of questioning the appearance of an object before one’s eyes, has changed very little through the millennia. The ancient Egyptians stared at fish in a way comparable to the Byzantines on the Bosporus or to Matisse in the Mediterranean. What has changed, according to history and ideology, is the visual rendering of what artists dared not question: God, Power, Justice, Good, Evil. Trivia could always be visually questioned. This is why exceptional drawings of trivia carry with them their own ‘here and now’, putting their humanity into relief.

Between 1603 and 1609 the Flemish draughtsman and painter Roelandt Savery travelled in Central Europe. Eighty drawings of people in the street – marked with the title ‘Taken From Life’ – have survived. Until recently they were thought to be by the great painter Pieter Bruegel.

One of them, drawn in Prague, depicts a beggar seated on the ground. He wears a black cap; wrapped round one of his feet is a white rag, over his shoulders a black cloak. He is staring ahead, very straight; his dark sullen eyes are at the same level as a dog’s would be. His hat, upturned for money, is on the ground beside his bandaged foot. No comment, no other figure, no placing. A tramp of nearly four hundred years ago.

We encounter this today. Before this scrap of paper, only six inches square, we come across him as we might come across him on the way to the airport or on a grass bank of the highway above Latife’s shanty-town. One moment faces another and they are as close as two facing pages in today’s unopened newspaper. A moment of 1607 and a moment of 1987. Time is obliterated by an eternal present. Tense: Present Indicative.

In the second category of drawings, the traffic, the transport, goes in the opposite direction. It is now a question of bringing to the paper what is already in the mind’s eye. Delivery rather than emigration. Often such drawings were done as sketches or working drawings for paintings. They bring together, they arrange, they set a scene. Since there is no direct interrogation of the visible, they are far more dependent upon the dominant visual language of their period, and so are usually more datable in their essence – more narrowly qualifiable as Renaissance, Mannerist, eighteenth century, or whatever.

There are no confrontations, no encounters to be found in this category. Rather we look through a window onto a man’s capacity to dream, to construct an alternative world in his imagination. And everything depends upon the space created within this alternative. Usually it is meagre – the direct consequence of imitation, false virtuosity. Such meagre drawings still possess an artisanal interest (through them we see how pictures were made and joined – like cabinets or clocks), but they do not speak directly to us. For this to happen, the space created within the drawing has to seem as large as the earth’s or the sky’s space. Then we can feel the breath of life.

Poussin could create such a space; so could Rembrandt. That the achievement is rare in European drawing may be because such space only opens up when extraordinary mastery is combined with extraordinary modesty. To create such immense space with ink marks on a sheet of paper one has to know oneself to be very small.

Such drawings are visions of what would be if … Most record visions of the past which are now closed to us, like private gardens. When there is enough space, the vision remains open and we enter. Tense: Conditional.

Finally, there are the drawings done from memory. Many are notes jotted down for later use – a way of collecting and of keeping impressions and information. We look at them with curiosity if we are interested in the artist or the historical subject. (In the fifteenth century the wooden rakes used for raking up hay were exactly the same as those still used in the mountains where I live.)

The most important drawings in this category, however, are made (as was probably the case in the Picasso sketchbook) in order to exorcise a memory which is haunting – in order to take an image out of the mind, once and for all, and put it on paper. The unbearable image may be sweet, sad, frightening, attractive, cruel. Each has its own way of being unbearable.

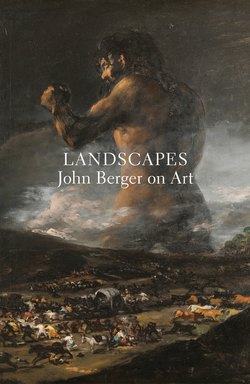

The artist in whose work this mode of drawing is most obvious is Goya. He made drawing after drawing in a spirit of exorcism. Sometimes his subject was a prisoner being tortured during the Inquisition to exorcise his or her sins: a double, terrible exorcism.

I see a red wash and sanguine drawing by Goya of a woman in prison. She is chained by her ankles to the wall. Her shoes have holes in them. She lies on her side. Her skirt is pulled up above her knees. She bends her arm over her face and eyes so she need not see where she is. The drawn page is like a stain on the stone floor on which she is lying. And it is indelible.

There is no bringing together here, no setting of a scene. Nor is there any questioning of the visible. The drawing simply declares: I saw this. Historic Past Tense.

A drawing from any of the three categories, when it is sufficiently inspired, when it becomes miraculous, acquires another temporal dimension. The miracle begins with the basic fact that drawings, unlike paintings, are usually monochrome.

Paintings with their colours, their tonalities, their extensive light and shade, compete with nature. They try to seduce the visible, to solicit the scene painted. Drawings cannot do this. They are diagrammatic; that is their virtue. Drawings are only notes on paper. (The sheets rationed during the war! The paper napkin folded into the form of a boat and put into a raki glass where it sank.) The secret is the paper.

The paper becomes what we see through the lines, and yet remains itself. A drawing made around 1553 by Pieter Bruegel is identified in the catalogues as a Mountain Landscape with a River, Village and Castle. (In reproduction its quality will be fatally lost: better to describe it.) It was drawn with brown inks and wash. The gradations of the pale wash are very slight. The paper lends itself between the lines to becoming tree, stone, grass, water, cloud. Yet it can never for an instant be confused with the substance of any of these things, for evidently and emphatically, it remains a sheet of paper with fine lines drawn upon it.

This is both so obvious and, if one reflects upon it, so strange that it is hard to grasp. There are certain paintings which animals could read. No animal could ever read a drawing.

In a few great drawings, like the Bruegel landscape, everything appears to exist in space, the complexity of everything vibrates – yet what one is looking at is only a project on paper. Reality and project become inseparable. One finds oneself on the threshold before the creation of the world. Such drawings, using the Future Tense, foresee, forever.