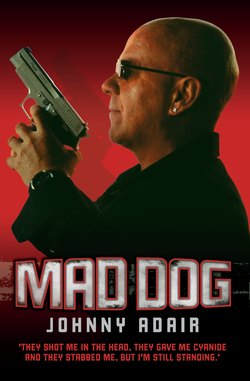

Читать книгу Mad Dog - They Shot Me in the Head, They Gave Me Cyanide and They Stabbed Me, But I'm Still Standing - Johnny Adair - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

OLD GUARD, YOUNG TURKS

It wasn’t long before I started getting noticed by the UDA leadership. The Shankill is a pretty small place and it was no secret that there was a hard core of us who were regularly fighting with Catholics. They saw me as someone who was bitter and game to get his hands dirty. That was just what they wanted.

The problem at the time was that the UDA was a shambles run by drunks who were little more than small-time bullyboys. The last thing they were was a military organisation who were able, or even willing, to take on the Republicans. Virtually no operations were being carried out and the commanders were more interested in making sure that they had enough money to cover their drinks bill in whichever of the 86 pubs on the Shankill that they used.

If they weren’t boozing, they were in the bookmaker’s placing bets, or coercing kids into petty crimes to fund the rest of their day. My father, on his way home from work, would walk past them as they lay slumped in doorways. He used to say they were nothing more than ‘scumbags who never worked or wanted’.

None of us had any interest in signing up to become part of that. If I was going to volunteer, it would be to join the UVF, as at the time they were the only ones taking the fight to the Nationalists. But in the end I didn’t have a choice. One night I was summoned off the streets to the UDA headquarters and told that I had to sign up.

The guys in charge stank of booze and barked at us that they knew everything we were up to. The first time they asked us to join I managed to dodge it. But within days I was hauled back in and it was made clear that unless I did what I was told I would be taking a bullet.

Donald Hodgen, Jackie Thompson and Skelly were all in the same boat. None of us wanted to get involved with the UDA but we were all made an offer we couldn’t refuse. While the UDA guys were drunks, they would still have had no problem shooting you if you didn’t do what you were told. The four of us were told that we had to be back at the headquarters in a week for the swearing-in ceremony, otherwise there would be trouble.

In reality, what was supposed to be an initiation into a paramilitary organisation was little more than a shambles that confirmed what we all thought about the UDA. There were no hoods or guns, just two men holding a bit of paper. One by one we were made to read out the oath and soon it was my turn:

I, Johnny Adair, am a Protestant by birth and, being convinced of a fiendish plot by republican paramilitaries to destroy my heritage, do swear to defend my comrades and my country, by any and all means, against the Provisional IRA, INLA, and any other offshoot of republicanism which may be of similar intent. I further swear that I will never divulge any information about my comrades to anyone and I am fully aware that the penalty for such an act of treason is death. I willingly take this oath on the Holy Bible witnessed by my peers.

It was all a load of nonsense and I saw nothing in the early days that convinced me otherwise. The only reason they wanted new faces was to bring them more of the £1 weekly dues that had to be handed over by each member. But there was no way to get out of it. The last thing they were going to let you get away with was not turning up with the money. If you let them down, they wouldn’t think twice about coming round to your house, dragging you into the street and battering you senseless in front of your wife and kids.

I still desperately wanted to see action and take on the IRA, who were slaughtering our people. But the UDA in their present state weren’t going to allow me to do that. Skelly, Hodgen, Thompson and I were all placed in the C8 brigade. The only way I could see us breaking free of the mess was to get into the Ulster Freedom Fighters, the UDA’s military wing. But the UFF hadn’t been seen or heard of in years. The rest of the organisation was rotten and choked with intelligence informants, so with no alternative on the horizon I just got on with being an ordinary member, paid my dues and kept my head down.

I remember one of the senior members walked into a room half-cut and assembled a sawn-off shotgun. He put two cartridges in before turning round, pointing the weapon at us and slurring, ‘I’m looking at all youse now. If anybody ever thinks of escaping, or gives a statement when arrested, I’ll blast you to death myself.’ That was the extent of their military ability.

The first time I was called on to carry out any sort of operation was when I was told to help hijack a bus. The UDA were fighting for segregation for Loyalist prisoners, who were mixed in with Republicans in Crumlin Road jail. We were sent out to hijack a bus to help create the pressure they wanted to put on the authorities. A number of operations had been planned for that night, but ours was the most elaborate. Everything went according to plan and we caused a bit of grief.

A couple of weeks later, one of the guys from the hijacking team was lifted by the police for something unconnected. He cracked and, in exchange for dropping the other charges he was facing, offered them details of who had been involved in grabbing the bus. Within hours the police broke down my father’s front door, arrested me and took me to the Castlereagh Holding Centre under the Prevention of Terrorism Act of 1974.

It was the first time I was lifted under the Act and I felt proud. But at the same time I’d heard the stories about the infamous Castlereagh. Suspected terrorists from both sides were taken there and interrogated. If the authorities didn’t get what they wanted that way, it was beaten out of you.

I managed to get through the first interview. I was asked if I was a member of any paramilitary organisation. I denied it. They put it to me that I’d hijacked the bus. Again I denied it. I was beginning to feel I had nothing to worry about, as they were giving me everything they had yet they had nothing on me.

Then the pressure was turned up. The detective leading the questioning was a tall thin guy with swarthy skin. Just before the first session ended, he said to me, ‘Now listen, you. I’m going to lock you up now, and when I come back I’m going to show you the proof that you hijacked the bus, and when I do that you’re going to be in trouble.’

I was still convinced they had nothing, so by the time he came back in to have another go I was feeling pretty cocky. I’d made it through the first interview and I hadn’t been battered or nailed to the table. Clearly the stories I’d heard were wrong, or I was too smart for them.

Then the copper came back into the room. He was pretty casual, peeling an orange and drinking milk from a carton. Then he threw a bit of paper down on the table and asked me to read it. It was a blow-by-blow account of what had happened, signed by the guy who had cracked. It was authentic and I knew I was in trouble. I had no idea what to do. The UDA hadn’t given us any schooling on what to do if you were arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. I thought the statement meant that I was done and there was no way out of it. I decided to try to bluff my way out of it. I told the detective that his source must be lying. For that I got a cuff across the side of the head, then another. It was the first time I’d been put under any sort of pressure, and I coughed to the lot.

The result was that I was remanded until my court date. Although I had ‘previous’, it was all minor offences, and when I appeared I was handed a suspended sentence.

While I was on remand, one of the guys went to see the commander of C8 to get my welfare money, which is paid out to prisoners while inside. All he was told was that he would see what he could do. It would have been just £7 a week, but it was drinking money that they were losing out on. To make matters worse, the rat who had stuck me to save his own skin was left alone. I was promised that retribution would be handed out, but nothing happened. All it did was make me realise more and more that the UDA was decaying at the core. All I could do was hope that somewhere down the line the UFF would make a reappearance and offer me an out. During the 1970s they had been the main players in carrying out anti-IRA operations. A resurgence of the UFF would let me get away from the deadwood, who were just in it for the free booze.

Things improved when I was asked to try out for the elite Ulster Defence Force. It had been set up in 1983 and was the brainchild of the UDA’s number two, John McMichael. The idea was to take the youngest and keenest volunteers and see what they were made of, while at the same time training them up in combat techniques. A camp was set up at Magilligan Point in County Londonderry and was run by former British Army soldiers sympathetic to the Loyalist cause.

Among them were a former Royal Marine and UDA member, and Brian Nelson, who had served in the Black Watch. It later emerged that Nelson was an agent for the British Army’s Force Research Unit, or FRU. He had been brought up on the Shankill and signed up at the age of 17. When he was discharged in 1969, he signed up for the UDA. Five years later he was convicted of kidnapping and sent down for seven years. On his release Nelson had a change of heart and decided that he wanted to help the army and offered his services to the FRU. He was to become a major influence on the early operations of C Company, providing a lot of the intelligence, but he was also inadvertently to help get rid of the old guard of the UDA and clear the path for me and other new blood, together known as the Young Turks, to take over.

When McMichael decided it was necessary for the UDF to be set up, there was a real fear that we were getting ready for all-out war with the IRA. His plan was to make sure that we were ready for it. Every Sunday I would volunteer to go to the military camp and take part in training. We were given military uniforms and camping gear, and taught map-reading, survival techniques and surveillance. At the end of 18 weeks, you were tested on what you had learned and from that the leadership decided if you were going to be part of the elite unit.

With Nelson one of the main players in the running of the camp, and the rest all being former armed forces men, I believe that the whole thing wasn’t the idea of McMichael, but in fact the British intelligence services. They wanted to have a set of people they could call on for operations that they couldn’t be seen to be carrying out themselves.

These secret training sessions lasted about four hours, although occasionally we would be taken away on exercise for the weekend. Davey Payne, from Crumlin Road Opportunities, was now back on the scene and was heavily involved in deciding who made the grade. The good news for me was that he remembered me from the youth project and made sure that I wasn’t held back. Others who had been asked to try out were asked if they were prepared to put their life on the line for the UDF.

While the intelligence services were almost certainly behind the training camp, the UDF’s course still enabled its leaders to sort out who were the good men who could be trusted to take on major jobs. I was at the top of their list.

At the end of the training, Andy Tyrie, the Supreme Commander of the UDA, came and oversaw a passing-out parade and presented the successful trainees with their silver or gold wings. Only one in five of those who tried out for the UDF actually made it through to the end.

There was one crucial problem with the whole thing: there were no weapons or explosives training. How were we going to take on and defeat a well-armed and trained organisation like the IRA? If they had seen what we did instead, they would have pissed themselves laughing. There were guys running about with sticks pretending they were guns and motioning like they were lobbing grenades to simulate an ambush. It was embarrassing, like kids pretending to be soldiers. That would change, though, with a change in the leadership.