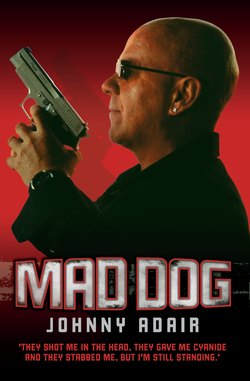

Читать книгу Mad Dog - They Shot Me in the Head, They Gave Me Cyanide and They Stabbed Me, But I'm Still Standing - Johnny Adair - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE BUZZ

ОглавлениеViolence was a way of life on the Shankill Road. Growing up there as a kid was like having the biggest and best playground right on your doorstep. There was always danger, always something happening, and that was what made it so exciting. I was born on Sunday, 27 October 1963, during a period when Northern Ireland was experiencing relative peace and stability. An IRA border campaign the previous year had disintegrated without getting very much support.

I was the seventh child of Mabel and Jimmy Adair. Our house off the Old Lodge Road in Belfast was right on the front line of the divided Protestant and Catholic communities, slap bang in the middle of what would descend into a war zone. West Belfast would remain my home until my family and I were forced to leave in 2003.

Like any other family in the area, we were poor. My parents, five sisters and one brother and me were all crammed into a traditional two-up, two-down terraced house with an outside toilet. Dad worked at the Ulster Timber Company on Duncrue Street in Belfast Docks, and did his best to feed his family and provide for us all. He was a very quiet man who didn’t drink or smoke, and there wasn’t a bitter bone in his body.

My family had no history of involvement with paramilitaries and there was certainly nothing there that hinted at the path I would later take. I firmly believe that if I had grown up anywhere but west Belfast I wouldn’t have got drawn into the Troubles and spent so many years behind bars, let alone become the leader of the UDA. Growing up on the Shankill wasn’t a normal childhood, but it was all I knew. There was no stage when I thought to myself, I want out of this place. Besides, we were a poor family, so where were we going to go? It was what I was born into and what I had to accept.

When I was very young, there was little of the vicious divide and hate-fuelled violence that would rip the area apart. The two communities lived side by side and I clearly remember playing with Catholic kids in the street when I was growing up. They lived alongside us and, as far I was aware, there was no difference between us.

All that changed during a week of violence in August 1969. Tensions had been bubbling under in Northern Ireland for most of the year. Leading Loyalists were unhappy with the liberal attitudes of the Prime Minister, Captain Terence O’Neill. They believed that his policies were far too moderate, and they were going to do something about it. Forces within the Ulster Protestant Volunteers and the Ulster Volunteer Force collaborated to stage a series of bombings that were made to look like the work of the IRA.

In March of that same year, the Castlereagh electricity substation, which supplied power to the south and east parts of Belfast, had been blown up. The following month, water pipes in Dunadry in County Antrim, the Silent Valley reservoir in the Mourne Mountains and at Lough Neagh were all targeted. The city was brought to its knees and the IRA were getting the blame. O’Neill resigned, but it didn’t stop the trouble. Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland were now on a collision course.

Trouble first erupted in Londonderry, where Harold Wilson’s Labour government had given the go-ahead for the annual Apprentice Boys’ march around the city walls on Tuesday, 12 August 1969. The march sparked two days of violence in the Catholic Bogside area of the city and, as word quickly spread, clashes flared up in Belfast.

The people on the Shankill began to feel they were under siege and that the IRA were coming to force them out of their homes. After seeing the trouble in Londonderry, the Irish Prime Minister, Jack Lynch, inflamed the situation in a television address by saying that action was needed and that a united Ireland was back on the cards. Within days, the two communities turned on each other. Rioting and looting left seven people dead. Protestants now knew they were under attack, and a backlash followed that led to Catholics being burned out of their homes.

Only five at the time, I understood very little about what was going on. I remember waking up and finding the street jammed full of police cars and fire engines as they attempted to deal with the mayhem from the night before. While I’d been asleep, a mob had gone to the homes of suspected Catholics and set them on fire. The kids I’d played football with were gone and their homes were still smouldering.

My age didn’t prevent me from knowing the difference between a Protestant and a Catholic. I knew also that it was the Catholics who had been forced out of their homes before they were torched. What I didn’t know was why.

I remember hearing people say, ‘The Taigs have been burned out,’ and I’m pretty sure that was the first time that I thought Catholics must be bad people. After that week of violence, everything changed for everyone, and soon it became the norm for us to hate them and them to hate us without question.

As I grew up, the differences between Protestants and Catholics became more extreme and increasingly violent. Our house was only a few hundred yards from the staunchly Republican Ardoyne area, on the front line, where the tension was worst and the conflict most ferocious.

Most nights, from my bed in the attic of the house, I could hear gun battles raging between the British troops and the IRA. My brother Archie and I would listen to the crack of automatic fire and try to work out what was going on. It was frightening and exciting at the same time. I would look out of the window and see the troops, crouching behind protective barriers, open fire, then take cover as their targets returned the attack. This wasn’t watching a film or playing with Action Man: it was right on your doorstep and better than any movie you were ever going to see.

When the gun battles really kicked off anyone who was outside was hauled back into the house. All the lights would be turned out and all the family would huddle together in the same room. The scream of the sirens and violent explosions meant that you did what you were told. There was always a risk that a stray bullet might get you, or that armed men might come crashing through the front door. It was so bad that we had to creep about hunched down to get from room to room. Despite the danger – which was the same for every family – you never wanted to miss out on any of the action. Whenever possible, someone would be stationed at the window and give us a running commentary.

The morning after a big battle was always something to look forward to. At first light, I would get up and scour the streets for trophies. Thousands of spent cartridges would be strewn everywhere, and the makeshift shelters that the combatants had used would be peppered with bullet holes. My pals and I would inspect the scarred stone and wonder how anyone had managed to make it through the night.

After a night’s trouble, we would also look for bullet heads that weren’t damaged, stick them in a glass of Coke to shine them up and put a hook on them so we could wear them on a chain.

The soldiers were on the streets all the time and any chance I got I would pester them. Most of the time they were happy to show you their guns, take out the magazine full of bullets and let you have a look. They were armed with SLRs loaded with huge brass 7.62mm bullets.

As well as the army, the Tartan Gangs would be roaming the streets. They were shaven-headed teenage Loyalists who hung around on street corners wearing Wrangler jackets and stonewashed jeans with tartan patches, Ulster badges or pictures of King Billy sewn on to them to make sure everyone knew what they were about. They weren’t paramilitaries, just teenagers out looking for a fight with Catholic lads. I would watch them getting ready for a fight, or winding up the opposition and think to myself, I want a bit of that action.

I was so in awe of the gangs that I would do everything I could to look the same. They were happy to get us involved at the age of ten, or sometimes even younger. At first, we did simple things, like tipping them off when a car would be coming out of a Catholic area so they could ambush it. There was no thought about who was driving the car; it had come out of a Catholic area so it was good enough to be targeted. They would lie in wait until the word was given the motor was on its way, then they would spring from their boltholes into action, peppering it with stones, bottles, anything they could get their hands on.

From there you graduated to the next level: making a petrol bomb. They taught us to get our hands on a large milk bottle, a small amount of petrol, a bit of sugar and a rag, and away we went. Whatever they wanted, sourcing missiles to be thrown or dragging petrol bombs down to the barriers, I was glad to do it. There were thousands of kids on both sides of the peace line who were delighted to get their hands dirty. It was a real buzz and we were proud to be helping the paramilitaries. Many boys want to be soldiers when they grow up. I wanted to be like the uniformed paramilitaries who roamed the streets to protect our community.

It was a war zone, a constant war zone. Almost every night the Tartan Gangs would gather at the top of our street, ready to cause mayhem. All I wanted to do was get stuck in. I was only a kid, but the feeling of running with hundreds of men spoiling for a fight was something else.

When the police or the army turned up to try to keep the sides apart we would just give them a hard time for as long as we could get away with it. Nothing beat getting close to an army vehicle, waiting until the last moment and then throwing your stone inside it as hard as you could. Hundreds of stones would be raining down on the vehicle, but, if you thought one was yours, it made your night.

It was also good to keep in with the UDA guys. As well as looking after the community, they also policed it. I remember wanting to help a guy called Kenny Slavin when I saw him tied to a lamppost. His fingers had been broken, his hands were secured behind his back and he was plastered in blue gloss paint. I used to hang about with his brother and I was about to help him but the UDA men who were standing near by growled at me that he was a housebreaker and sent me on my way.

One of the UDA guys I looked up to was Norman McGrath. I knew him because he lived on Cunningsby Street, round the corner from our house, and I would see him every now and then when I was hanging about on street corners with my friends. Norman was a teenager and the kind of bloke I respected as a role model. He was one of the guys who manned the barricades and defended us against whatever the other side were doing.

In 1971, Norman was gunned down in the street by Republicans who opened fire on him from a passing car. If he had been shot dead I doubt I would have remembered him: he would have been mentioned in passing as the latest man killed. But Norman survived, though he had to have his leg amputated. Before long he was back on the streets, and to me this made him a hero. The IRA had tried to kill him but failed. Norman, the guy who gave me a few pennies to go to the shops with, had taken a bullet for me.

On 11 June the following year, still only 18, Norman was shot dead by British soldiers on Manor Street. There was always trouble at this notorious flashpoint which had Protestants at one end and Catholics at the other. The night Norman was shot, one of the fiercest gun battles took place in Oldpark. At the time locals said he wasn’t armed when two soldiers from the Royal Regiment of Wales opened fire on him from close range. But the RUC claimed to have found seven 7.62mm bullet cases close to his body. Experts also told an inquest they couldn’t rule out that Norman had fired a gun during the rioting, because of the amount of residue on his cuffs.

What happened to Norman made no difference to our attitude. Nor did the shooting of a pal as we rioted as kids. I was hanging about on Manor Street one evening with my best friend Billy Rea, waiting for trouble to start. The two sides were locked in a face-off, waiting to see who would make the first move. There was the usual trading of insults and missiles. Then, out of nowhere, a gunman appeared. I remember him clearly because he wasn’t wearing a hood or making any effort to disguise who he was. He opened fire with a bolt-action rifle. Seeing the weapon and then hearing the bang as he let off a round scared us. Suddenly it was more than just throwing missiles. There was real danger and it was right in front of us.

We dashed for the safety of our end of the street. I was running for my life, with Billy in front of me. The next thing I knew he fell to the ground, almost in slow motion. He had been hit in the foot. My mate was screaming at me, ‘I’ve been shot! I’ve been shot!’ That was the danger of getting involved, but I still loved it. For me, the constant threat of serious consequences was far outweighed by the thrill of being out on the street seeing some action.

It was around that time that a feeling of bitterness started to grow in me. Seeing my community attacked and people getting killed made sure it kept eating away at me. There wasn’t a lot my parents could do to stop me getting involved, not least because it was right on your doorstep. It wasn’t as if I was getting on a bus and travelling miles to get involved in trouble. It was just there, all the time.

Everyone was in the same boat and the community stuck together. After a night’s trouble, the mothers would meet in the street and gossip about what had been going on as they swept up the bottles and rocks that littered the ground.

Whenever I got caught rioting by the police, they would bring me home rather than lock me up. My father cuffed me as much as any other dad, especially when I was getting escorted home by the coppers most nights of the week. But, even though I was the one causing the trouble, he was always sure to have a go at them first. He would give them a mouthful and ask if they had nothing better to do with themselves. I never got away with it, though, because once he was done with them I was next in line.

My father wasn’t at all interested in the Troubles. Most of his friends were Catholics, many of them members of the same pigeon club as him. I remember being taken to their homes and told that they were Catholics but they were OK and there was no need to be afraid of them. All the same, the thought was still in the back of my mind that we were on enemy territory.

My father felt that since he had no involvement or interest in any of the fighting he was immune from it. He thought, I’m not a bigot, so I can go where I want and do what I want. It didn’t always work like that. He was beaten up while walking his dog in the Waterworks Park because he was a Protestant in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was nothing too serious, just a couple of black eyes and some bruises. Had it not been him, it would have been someone else.

I was in no way a special case, or a kid who had strayed way over the line. There were plenty of other kids in Belfast who were up to exactly the same things.

With all this going on, it is easy to see why I was never really that interested in school. I started in 1969 at Hemsworth Primary School, just around the corner from my house. By the time I started at Somerdale School six years later, I couldn’t wait to get out of the system. The only thing that kept my attention was the fighting. On the bus that we took to school there would be Catholic girls going to Our Lady of Mercy School. There were fights nearly every morning. Spitting, kicking, anything went. At nine in the morning on the way to school, and then again at midday when you got lunch from the chippie, you would be fighting with the guys from St Gabriel’s. I was always getting brought into school by the police because I spent most of my lunchtimes fighting with Catholic kids from that school. It was petty stuff, but the cops would still lift me and take me back to face my headmaster. I still have scars from the constant fighting.

There were days when we couldn’t make it to school because the road had been sealed off after the fighting of the previous night. At other times we would be allowed to pass by burned-out cars, buses and other smouldering wreckage from the skirmishes that had raged just hours before. All the way to the school gates the consequences of the fighting were there in full view.

Most mornings I would get some sweets from the local shop to take to school. But it wasn’t always that easy. One day I couldn’t get into the shop because the body of a Catholic man had been dumped in the alley next to it. He had been repeatedly stabbed. The police were all over the place trying to stop people getting in the way of the forensic team, but I was still able to see the body lying on the ground, wrapped in plastic sheeting.

The older I got the more I wanted to know what the fighting was about and why our street looked like a war zone nearly every day. When you heard the family talking around the kitchen table about another Protestant man being murdered or wounded for no reason, that was when the hatred started to grow inside you and you wanted to know why it was happening. In fact, in Belfast it was easy to educate yourself. The gable ends of buildings were covered in huge murals that celebrated the heroes of the conflict and there were Orange Walk parades, which were all about displaying our culture. The city was stark in its contrasts, so becoming well versed in your side’s beliefs wasn’t difficult.

It was also a smart idea to make sure you were streetwise. If you didn’t, it was easy to get into all sorts of trouble. There were parts of the city that were no-go zones. Even on your own patch, there was absolutely no guarantee that you were safe.

I was only 13 when I saw the aftermath of the murder of 45-year-old bus driver Harry Bradshaw during the Loyalist workers’ strike in May 1977. I was messing about on the roof of the entrance to a derelict cinema on Crumlin Road when the noise of gunfire filled the air as the double-decker bus pulled up. I had the perfect view of everything. After hearing the crack, crack, crack of his weapon, I saw the assassin run up the street with a snorkel jacket done up tight to hide his face. I didn’t think twice about getting down off the roof to see what had happened. In situations like this, you had to get there as fast as you could, because the minute the cops turned up they told you where to go.

I remember looking at the driver, still seated at the wheel of the bus, and watching him turn grey in the daylight. One of the passengers had opened his shirt and was trying to help him. I could see the bullet hole, but there was no blood coming out of it. Thinking that this meant he would be OK, I legged it before the police turned up.

A coalition of the UDA and the Reverend Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party had organised the workers’ strike. It was designed to put pressure on the politicians who were running the country at the time, but, when it failed to get the community’s backing, intimidation tactics were rolled out.

Days before his murder, Harry Bradshaw had been attacked by a female passenger who hit him over the head with an umbrella and insisted that he should take part in the strike. The father of five decided to work instead and as a result was killed.

Kenny McClinton carried out the hit and also that on a Catholic man called Daniel Carville. McClinton was a founding member of the UFF’s C Company, of which I would later become military commander. He was one of the hardest men in Ulster, and even when they locked him up he was still fighting with Republicans. Then one day he found God, turned his back on all the violence and became a pastor. He knew my father, and I met him for the first time at my dad’s funeral. Throughout most of my time behind bars, he wrote to me telling me to take the route that he had. McClinton had hung around in the same places as I had and thought that for this reason I would respect him and listen to him.

Even as a kid I had the habit of being in the wrong place at the right time. Our main place for hanging about was outside the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes in Century Street. Known as the ‘Buff Club’, this was a favourite haunt of prison officers from the notorious Crumlin Road jail, which housed terrorists such as Lenny Murphy, who was one of the ‘Shankill Butchers’, and the IRA informer Sean O’Callaghan. Outside the Buff Club I would meet up with friends of that time like Jackie Thompson and Mark Rosborough. Sometimes William ‘Winkie’ Dodds would turn up and join in the drinking on the street.

One night a screw came out of the club, clearly having had a lot to drink. We started to take the piss out of him because he could hardly stand up straight. The next thing, he pulled out a gun and started firing at us. He didn’t miss by much. The police were called and later he was thrown out of the Prison Service.

When I was 15, I saw the dead body of George Foster at the same place just after he had been gunned down by the IRA. It was 14 September 1979 and I was with a couple of the lads at the usual spot when there was a loud crack of gunfire followed quickly by a screech of brakes. The first thing we did was rush round to see what had happened. I’m not sure what I thought I was going to do when I got there. Foster, who was married with two kids, and three other prison officers regularly went for lunch in the Buff Club and they were returning to work when the IRA gunmen made their move.

Earlier that day, the killers had hijacked the car that was to be used in the hit. Later, around the corner from the club, they sat in the orange Fiat Strada waiting for their targets. When the three men appeared, the IRA team followed them into Century Street and let them get into a car before opening fire wildly. Foster was struck in the head, while one of the other men was hit in both arms. When I got to the scene Foster was already dead, his body slumped in the car. Lying next to the dented car was his blood-spattered pack of Craven A cigarettes. He must have had them in his hand when the assassins struck. Another guy nicked the smokes and puffed away on them. Stealing from the dead – not even I would do that.

Foster, who was 30, had joined the Prison Service two years earlier, having previously been a member of the UDR, an infantry regiment of the British Army. A guy from west Belfast was later given 20 years after pleading guilty to his manslaughter. The gunman also got two life sentences for the killing of two soldiers, Private Christopher Shanley and Lance Corporal Stephen Rumble.

Five days later, just 200 yards away from where Foster was killed, the assistant governor of Crumlin Road Prison, Edward Jones, was shot by the IRA as he sat in his car at traffic lights. A car drew up alongside the father of ten and the gunman unloaded several shots from a large-calibre revolver. Sixty-year-old Jones had worked in the prison for 33 years when they took him out.

Growing up among the rioting and the mayhem that gripped the area was exhilarating for a kid. Of course it was frightening – the flashing lights, the explosions, the tension and hatred – but that was what gave you the buzz. The older I became and the longer I lived in the streets of Belfast, the more the bitterness got a grip of me. I didn’t wake up one morning and decide: I want to be a paramilitary. I went through a lot before I got there. The only difference between me and an IRA man is that it says ‘Roman Catholic’ on his birth certificate and ‘Protestant Presbyterian’ on mine. But that wasn’t going to stop the mutual hatred.