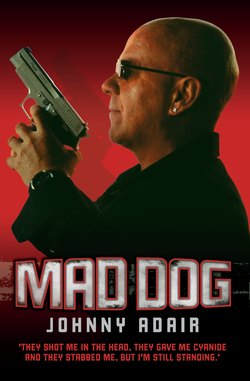

Читать книгу Mad Dog - They Shot Me in the Head, They Gave Me Cyanide and They Stabbed Me, But I'm Still Standing - Johnny Adair - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеI didn’t see the gunman coming. It was over an hour into the gig when he made his move. The only light illuminating the faces in the crowd came from the stage. My features were slightly disguised by a beanie hat pulled down on my head, but he knew it was me.

I heard the bang of the gun a split second before I felt the pain. It was excruciating. Pulling my hand back from Gina, my wife, I clamped it to the side of my head. I knew what was happening. I was sure I didn’t have long left.

Gina spun round to see what was going on. I could see her lips moving but there was no sound. I wasn’t going to collapse to the ground and no way would I scream and shout. If these were my last seconds, I was going to be strong.

As the people around me struggled to work out what was going on, I felt my hat being removed; it was saturated with blood. Everything was happening in slow motion. I turned round to eyeball the gunman but he was gone.

With my hat off, people realised who I was. It was clear I wasn’t going to get any help. One guy hurled a pint of beer in my face while the others kicked me to the ground. They weren’t part of the murder bid but they couldn’t believe their luck. Johnny ‘Mad Dog’ Adair, maimed with a bullet in the head right in front of them: time for some revenge.

I could see even less lying on the ground surrounded by the furious mob. Shafts of light came and went as kick after kick shook me. Gina and a friend were trying their best to hold my attackers back. I was hemmed in by a security barrier, but as the blows rained down I managed to prise it apart. I stumbled into an open patch and got a moment’s respite. But the mob poured through the gap after me and tried to inflict more damage. Twice more I was taken down but I managed to get back on my feet and broke free again. I staggered away, occasionally stopping, turning and trying to fend them off, before moving away as far as I could and then repeating the manoeuvre.

All the while I could hear Gina screaming for help. Nobody wanted to know. I managed to grab her and we headed for the protection of a security man in a fluorescent jacket. My face was covered in blood, so at first he didn’t recognise me and I hoped there was a chance he might get me out of there. But the IRA were running security that night and he turned his back and walked away. Gina and I were on our own now.

As fast as we could, we made our way out through the exit and on to the road. I clocked a taxi sitting at a give-way waiting for the traffic to clear. Frantically, I shuffled over, opened the door and jumped in. The cabbie knew who I was and did what he was told. The crowd threw some rocks at the car but we were in the clear. The driver, who I later learned was a Catholic, asked if I wanted to go to the hospital. That wasn’t an option. If it was the IRA who had been behind the hit, they would find out where I was and finish off the job. It was back to my house off the Shankill Road.

I’d believed I was no longer seriously at risk. It was April 1999 and Northern Ireland was in the middle of the peace process. Sure, there would always be a Nationalist who would have killed me, given the chance, but they weren’t competing with one another for the honour, as they had done in the early 1990s.

Even so, when the security team arrived to pick me up from the Maze Prison the day before the concert, some measures had to be taken. Around 15 men kitted out with radios and earpieces kept an eye on what was going on as I walked through the gate and got into one of the cars.

Coming out of prison was always a bit dodgy, as gunmen would have a good idea where you were going to be and when. But afterwards I would have the protection of the Loyalist community where I lived.

Once the UDA’s C Company security team were ready, we sped off back towards my home. In more dangerous days, it was common for a switch to be done en route so that any spotters waiting outside the prison would pass on incorrect details to any ASU planning an ambush. But I was happy that no change-over was needed now and I was convinced there was no risk in going to the gig. I couldn’t believe my luck when Gina told me that UB40 were playing in Belfast on a day when I was out on pre-release parole. I’d always been a big fan and I thought we would have a great night out.

By contrast, my minders weren’t at all happy about me going to the concert. Even though I wasn’t going into the heart of Republican Belfast, they were convinced there was a chance of trouble and wanted to send a team along with me. I wasn’t having any of it. Being surrounded by minders and heavies was only going to attract more attention. The guys had bought me a new Vauxhall Vectra, so Gina and I travelled in it to Belfast’s Botanic Gardens and planned to drive back. That way I was out in the open for less time.

That evening, the sun was still shining and I could hear the PA system as we got closer to the venue. As we made our way through the security check, I spotted a few faces I knew, all friendly, so there was nothing to worry about. Gina and I stood at the back of the venue, ready to enjoy the gig.

When the first band came on, a couple in the crowd started to look out of place. A tall guy and a woman had walked past us a couple of times, clearly checking me out. At first I hadn’t noticed them, but Gina was suspicious. Then they made their move. They strode towards me, the guy in front and the woman right behind him. I took a couple of steps forward to take any fight away from Gina. As I got closer to the man, he shouted out my name and nodded. I was relieved. It turned out I’d met him on a previous parole day. He was a friend of someone who knew my family and had come round to the house to have his picture taken with me. It was the only time during the whole evening that I was suspicious of anyone.

After the attack, the taxi driver took us to the home of trusted UDA man William ‘Winkie’ Dodds. My face was swollen from the beating and I was covered in bruises, but I could live with the pain. The C Company security team were brought together and it was decided I should be taken to the Ulster Hospital on the outskirts of the city. There were three other hospitals the IRA would check before that one if they were looking for me, and now I had the team with me to watch my back.

When I got to the hospital, I was expecting to be briefly looked at and taken straight through to surgery. As it happened, the hospital had very little experience in dealing with gunshot wounds. The nurses looked at me bemused as I explained that I’d been shot in the head, that there was only one hole and this meant the bullet was still lodged in my skull. They weren’t convinced. When I told them the round must have been damp, which would have prevented it from doing proper damage, it confused things even more and I got the impression they didn’t believe me. Eventually, I was taken for an X-ray and the slug showed up. Only then did they realise there was a problem.

‘Mr Adair, we have discovered a round in your head,’ the doctor told me. Well, I knew that. ‘The good news is it’s safe. You can have a bed for the night here or you can go home and come back in the morning, when there’ll be a surgeon here’.

It was a night of freedom from my cell in the Maze, and the last thing I wanted to do was spend it on a hospital ward. It was a tough night. I didn’t get home until the early hours and then, every time I put my head down, the pounding pain came back, so I hardly slept at all. My thoughts were veering from who was behind the attack to how lucky I’d been.

In the morning, I was re-examined, this time by a specialist, who told me that I would have to have the bullet taken out at some point but there was no hurry. I didn’t see the point in hanging on. If it was going to have to be done, it might as well be then and there.

In the theatre, I was given a local anaesthetic and so I was awake throughout the procedure. Although I couldn’t feel any pain, I could hear the medical instrument scraping my skull as the surgeon tried to get the bullet out. At one point, the medical team had to stop and give me another painkilling injection because the slug was deeper than they thought.

I saw the bullet when it was removed and dropped into a shiny silver dish. It was huge, a big lump of lead, and I was shocked. I knew my stuff and I’d guessed I’d been shot with a .22 round. This was way bigger than that. The doctor put it into a test tube and it was taken down to the police and we all had a look at it. Our best guess was that it was from a .38 and had been lying around getting damp since the Second World War.

When I got back to the Maze, I was sent for by the governor, who told me that he couldn’t believe the call when it came through from the hospital. A nurse had telephoned to say I was going to be late returning as I’d been shot in the head, but not to worry: I would be back. The governor didn’t know whether it was a wind-up or not.

The next concern was the backlash. The peace process being brokered by the British and Irish governments was at a delicate stage and the last thing the security services wanted was a witch-hunt. There were a number of reprisals without my knowledge but I called a halt to them as soon as I could. I met our spokesman, John White, and said, ‘I am alive, I have been through this before, and I don’t want the peace process wrecked.’

Word came through from the Republicans that the attack was nothing to do with them and I believed them. It was the best opportunity anyone ever had to kill me. He was firing from point-blank range and if it had been the Provisional IRA they wouldn’t have made a mess of it. Alternatively, they could have left a bomb under my car and blown me to bits.

The police were panicking and weren’t convinced that I wouldn’t let it escalate. The last thing they wanted was bodies turning up all over the city while the talks were going on. Two senior detectives came to question me in the Maze and let me know they had no evidence to suggest it was Republicans behind the hit. They were anxious to see what I was thinking about it, but I had no idea and told them so.

After showing me my beanie hat with the bullet hole in it, they asked me, ‘OK, what about Eddie? Do you know Eddie?’

My first thought was Eddie Copeland, a leading Republican activist in north Belfast, but again they insisted it was nothing to do with him. They were certain it was Catholic hoods who had seen an opportunity to kill me and given it a go. Did they have a weapon on them at the gig? Or did they spot me and send out and get one? I was there for hours, so they would have had the chance. Whoever it was had the nerve to get close to me and hold the gun in the middle of a packed concert. He knew what he was up to. Only one round was fired, but the guy knew that from close range this was all that was required. To have fired more would have given him less time to flee the scene.

The IRA murdered one of the main suspects. Ed McCoy was a 28-year-old drug dealer from the south of the city who was killed by IRA men masquerading as Direct Action Against Drugs. In May 2000, he was drinking in the pub with friends when two gunmen wearing false beards walked up behind him and shot him in the head and body. The gunmen’s getaway car was later found abandoned. McCoy was given a massive blood transfusion but died the next day. Other drug dealers that he had links to were also killed by the IRA.

The other name I was given came from a Catholic prisoner in Maghaberry. He came into my cell one day and threw down a newspaper that contained a memorial notice for someone called Whiteside. He was probably the guy who had shot me, and now he had committed suicide. His name meant little to me. I was just glad to be alive.