Читать книгу Canoeing with Jose - Jon Lurie - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE SEVAREID LIBRARY

When I catch wind of a newsworthy story, I feel like a burning man seeking water, driven to hit the road and investigate. I have experienced this compulsion repeatedly, working as a freelance journalist for magazines and newspapers across North America. It has motivated me to cover stories from Canada to Mexico, and from Washington, DC, to the Alaskan Arctic. But the first time it happened was in September 1988, weeks after the start of my first semester at the University of Minnesota.

The initial spark occurred when I took in a speech at Coffman Memorial Union. The speaker was a fiery Nicaraguan, a Sandinista rebel with a red beret. She railed against abuses inflicted upon Central Americans at the border. “The United States is starting wars against democratically elected governments in Central America,” she proclaimed. “The American government is backing violent dictatorial regimes and then imprisoning the individuals who arrive at the border seeking simple human dignity.”

Intending to write a paper based on this talk for my History of Civil Rights class, I scribbled notes on a yellow legal pad. The speaker was deadly earnest—the way people are when they’ve experienced war. And when she referred to the detention centers that had popped up in Texas as concentration camps, I knew I had to go.

My grandmother, Paulette Oppert, had lost a husband to the Nazis, placed her children (including my mother) in hiding during the occupation of France, and seen trainloads of Jews deported to the East. Maman had always taught me that my greatest responsibility was to remain vigilant against genocide. I was on this Earth above all, she often told me, to help make certain there was never another Holocaust. To this end, she had always encouraged me to write, and to keep a gun in the house.

Three days after hearing the Sandinista speak, I set out for the Rio Grande River Valley, 1500 miles south of Minneapolis. As I accelerated onto Interstate 35, blasting punk rock mixtapes, I felt as if I were finding my destiny. I had interviewed Maman extensively over the years, and I intended to write her biography. After years of searching for an identity, and having exprienced dozens of instances of anti-Semitism myself, I had settled on a personal narrative based on my grandparents’ involvement in the French Resistance. Maquis members served as guerilla fighters, underground newspaper publishers, and manufacturers of forged government documents. They fought alongside the American and British soldiers who liberated France from the Nazis. As I headed for the American concentration camps, I finally had a mission that paralleled this history.

Back home in Minneapolis after a week on the road, I submitted a 5000-word story to the professor who taught my History of Civil Rights course. He encouraged me to publish it, and so I addressed a copy to Steven Lorinser, editor in chief of the student-produced Minnesota Daily. I was ecstatic when he phoned to arrange a meeting.

I found Lorinser waiting for me at a secluded table in the Eric Sevareid Journalism Library. He was dressed in slacks, loafers, and a crisp shirt. His hair was neatly parted on the side and he comported himself like a professional. My head was shaved and I showed up in Chuck Taylors, a tattered sweatshirt, and frayed jeans.

Lorinser was impressed with the reporting I had done from Texas, and asked about my other interests. He called me gutsy, committed to printing my story in the Daily, and promised more opportunities for me to write for the paper.

I described my backpacking journeys in South America and Europe, and the extensive road trips I’d taken to every corner of the United States. As we talked, we discovered a shared love of the Northwoods and canoeing. I told him I’d spent five consecutive summers at a canoe camp on the Canadian border as a teenager, culminating in a 30-day paddle across northern Ontario. I went on to explain how those experiences had led to employment guiding youth on canoe and backpacking trips.

Lorinser’s face lit up like a match to birch bark. He asked if I knew of a book called Canoeing with the Cree.

I shook my head.

“It was actually written by that guy,” he said, pointing to a bust in the middle of the library. He went on to explain how Eric Sevareid had paddled from Minneapolis to Hudson Bay with his friend Walter Port, a distance of some 2300 miles. They undertook the expedition when they were just 17 and 19 years old.

After the journey, Lorinser continued, Sevareid graduated from the University of Minnesota, and went on to become one of Edward R. Murrow’s courageous correspondents, the first to report on the fall of Paris to Nazi forces in June 1940. When I learned that Sevareid had been denied the editor in chief position at the Daily following a controversial column he’d written in 1934, my admiration for him was boundless. And according to Lorinser, Canoeing with the Cree was his first published work.

I pumped Lorinser for details of Sevareid and Port’s route, astonished that there was a passage by waterway from Minnesota to Hudson Bay. But it had been years since he read the memoir, and he couldn’t recall much more than he’d told me already.

Animated by the exchange, Lorinser and I searched the Sevareid Library for a copy of Canoeing with the Cree. According to the card catalog, the book should have been shelved and available. But apparently I wasn’t the only one interested in this audacious trip.

We queried a librarian, who smiled unexpectedly. She called the book “a regional classic” and “Minnesota’s version of Huck Finn,” before apologizing sheepishly for the missing volume. “Some people forget to sign it out,” she explained, and then suggested that I check the university bookstore.

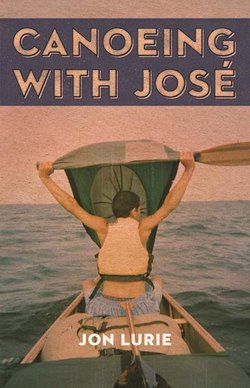

I hurried across campus and found a short stack of tan paperbacks on the “Minnesota Interest” table, surrounded by books on Vikings football greats, classic hot dish recipes, and the Twin Cities’ best fishing holes. The cover featured a photograph of a strapping Sevareid wearing baggy pants tucked into knee-high boots and a button-up khaki shirt, posing jauntily with hands on his hips. He could have passed for a Mountie, and he appeared to be at least 30 years old.

At the time, I was living in a dingy apartment above the CC Club. Every night the seedy Uptown tavern was crowded with punks, hipsters, and blue-collar regulars drinking Grain Belt from plastic pitchers and listening to the jukebox—a catalog of the thriving punk scene that pulsed on the streets of Minneapolis’s south side. Many of the musicians playing on these records were CC regulars: Grant Hart from Hüsker Dü, Bob Stinson from the Replacements, members of Soul Asylum, Blue Hippos, Run Westy Run, and Babes in Toyland.

I was generally seething at the state of the world, and when the jukebox rumbled with livid punk rock, crackling the linoleum tile on the kitchen floor until well after midnight, it resonated like the beat of my heart. But on the cool October night when I returned home from campus with a copy of Canoeing with the Cree, I longed for silence.

Had I judged the book by its cover, or by its opening lines, I would have rejected Canoeing with the Cree immediately. While I was just a few weeks into my first Native American studies class and my awareness of the history and culture of Minnesota’s indigenous people was still embryonic, I knew enough to dismiss the cover copy’s assertion that Sevareid and Port were the first to paddle from Minnesota to Hudson Bay. Given the long history of Native peoples and voyageurs traversing the vast system of waterways extending from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes, I was confident that this journey had been undertaken long before Sevareid and Port. Nor was I particularly impressed by the citation from Kipling that begins the first chapter, with its reference to “Red Gods making their medicine.”

As I turned the pages of Canoeing with the Cree that first time, however, I suspended judgment on the book’s grandiose claims, and on the racist attitude of its author. After all, when Sevareid and Port made their journey in 1930, indigenous people had only been granted American citizenship for six years (the Indian Citizenship Act having passed in 1924), their religious practices were strictly outlawed, and their culture had been decimated by government policies that forced thousands of Native children into boarding schools, where they were held away from their families, made to dress like white people, and severely punished for speaking their languages.

Instead, I read Canoeing with the Cree that first time as an adventure story. I burned to know the boys’ route. After launching at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers in Saint Paul, they had paddled up the Minnesota River and its tributary, the Little Minnesota River, to Browns Valley, Minnesota. From there, the boys portaged over the Laurentian Divide to Lake Traverse and descended the Bois des Sioux River to the Red River of the North, which led to Lake Winnipeg. Then they had paddled down the Nelson River, across a series of small lakes and portages to Gods River, and down the Hayes River to York Factory on Hudson Bay.

Canoeing with the Cree supplied me with something I had never experienced: a homegrown mythology. Theirs was not the tale of 17th-century voyageurs paddling 600-pound Montreal freighter canoes on the Great Lakes, nor the Anishinaabe’s sacred migration from the mouth of the Saint Lawrence through the Great Lakes to the land where food grows on the water. Sevareid and Port had grown up in a neighborhood less than five miles from my own and sought adventure in a used canvas canoe. They had embraced an ambitious vision and found the nerve to follow the water.

When I turned the last page of this extraordinary tale, the floor pulsing beneath me, I silently declared my intention to retrace their path to Hudson Bay as soon as possible. Little did I know that it would be 15 years before I realized this dream.