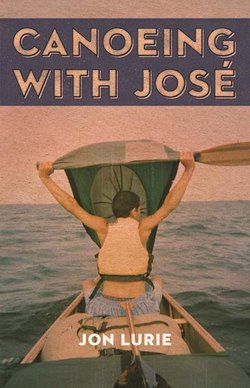

Читать книгу Canoeing with Jose - Jon Lurie - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJOSÉ

The spring of 2002 was brutal. I had lost my editorial job in Alaska, and it was obvious that my marriage of 13 years was swirling down the drain. I was 34 years old, and I decided to return to Minneapolis to write for the Native newspaper where my career in journalism had begun a decade before.

Over the course of the previous decade, my work for The Circle, Indian Country Today, the Sicangu Sun-Times, and other Native publications had led me to places and provided me with experiences accessible to few white people. I had met and befriended Native elders and philosophers, professors and activists, medicine men and political leaders. I had participated in Lakota ceremonies and learned from ordinary tribal citizens in cities and on reservations, from Rosebud to Pine Ridge, and from Arctic Village to White Earth, Upper and Lower Sioux, Isleta Pueblo, Bad River, and many others. These experiences had taken me far from my upbringing in a conservative Jewish household in Minneapolis, fulfilling in many ways what I longed for as a young man: to live a deeply meaningful life connected with the land of my birth. I had also come to understand the extent to which mainstream Americans were beneficiaries of the genocide of indigenous peoples, and it didn’t sit well with me. It never had, even when I was too young to know why.

In addition to reporting, The Circle had hired me to teach in their youth journalism program. I met José on the first day of the summer session, at The Circle’s office in south Minneapolis. He was sitting at a desk with two other interns, eyeing me suspiciously from beneath a powder-blue baseball cap. The program director introduced me, running down a list of my accomplishments: several hundred published articles in over two dozen papers and magazines, three nonfiction children’s books, 12 years reporting in Native American communities, and a brief tenure as the editor in chief of Alaska’s second-largest newspaper.

José kicked his Adidas up onto the table and leaned back in his chair. He yanked at a silver pistol that hung from a chain around his neck, and raised his hand as if saluting the Führer.

“Yes?” I nodded.

“Got just one question. Why they had to get some Nazi up in here to mess with our writing? You ever read New Voices? It says right there on the cover, The Voice of Native Youth. By the looks of things, you ain’t knowing a damn thing about Native youth.”

José’s hostility didn’t surprise me. I used his charge as an opening.

“I’m no Nazi,” I replied. “I’m a Jew. The only reason I’m in this country is because Hitler tried to kill my people in Europe. And I’m not here to mess with your writing. I’m here to help you say whatever you want to say.”

José pulled his feet off the table and let them land with a thud. “You tryna say you down and all that, tryna come off like you ’bout it? First off, I don’t need no editor. At Heart of the Earth Survival School, I’m the editor of the school paper. And I don’t need no thought police stepping on my First Amendment rights.”

The program director glanced at the clock. “It’s time to get working on your stories. Each of you will take a turn working with Jon. Who’s ready to go first?”

José stood, his bravado bolder than his lanky frame would suggest. “I’ll go. Ain’t no one gonna fuck with my shit.” He breathed up at my chin, then swaggered into the conference room with a cherry iBook under his arm.

José set the computer on the mahogany table and opened the lid. “You can’t say nothing ’bout this. You gotsta be down with the hip-hop game before you can say word one.”

A document titled “Ja Rule and 50 Cent Leave Blood on the Tracks” filled the screen. As I read the article, it became clear that this was José’s commentary on the latest feud between rival hip-hop artists. Such conflicts had led to the murders of some of rap music’s biggest stars in recent months.

José pulled a butterfly knife from his back pocket and whipped it around above his head like a rodeo ninja. “What can you even say? You ain’t down with the game, the youth, the Native Americans.”

“These gangstas gots to be bigger than that,” he wrote. “They gots to leave the beef char-broiling at Burger King and stick to making dope records. We all remember those who been felled by the bullet: Biggie Smalls, Tupac Shakur, and Notorious BIG. But ain’t nothing ever gonna bring ’em back. We can’t afford to lose no more of our voices from the ghetto to senseless murder and mayhem. I got a message for all you rhyme-slingers out there thinking you badder than Ice-T in NWA: Leave the damn blood on the tracks.”

I was impressed with the piece. José was writing in the language of hip-hop. He had a clear sense of intended audience. And he was good with metaphor.

There were some glaring factual errors that I hoped to take up with him, but in the meantime, the verbal battery went on. “You gotsta have street cred ta fuck with my shit. Man, they’d tear your punk ass up on the mothafuckin’ block.”

“You little bitch,” I interjected. “I was listening to rap music while you were still shitting your diapers.” I was genuinely irritated, but I was also taking a calculated risk. When I lived on the Rosebud Reservation I had worked part-time as a substitute teacher, and I quickly learned that one way to win the respect of a streetwise teen was to get in his face.

Occasionally, though, the strategy backfired.

José wasn’t laughing. He jumped out of his chair and stood over me, butterfly knife resting at his hip. “You calling me a little bitch?’

“That’s right,” I said. “Professionals understand that editing is part of the business.”

“You little bitch,” José hissed back at me. He put his hands on a long aluminum cabinet that stood against the wall by the door, then lowered his head and went silent.

The sudden hush worried me, and I took a more conciliatory tack.

“Come over here and sit down,” I said. “Let me show you how a few small changes could improve your article.” I scrolled down a page on the iBook. “In the final paragraph, where you say Ice-T was in NWA? He was never in NWA. You must have been thinking of Ice Cube.”

José pushed off the cabinet and clapped like a boxer doing push-ups.

“And here, where you list the names of the rappers who have been murdered: Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur, and Biggie Smalls? That’s not right. It’s true they were murdered, but Biggie Smalls and Notorious B.I.G. were the same guy.”

José’s cheeks went scarlet, and he squealed in falsetto, “Whaaat?”

“Fact checking–”

“Whaaat?” he sang out again, then bounced his backside off the aluminum cabinet. It rocked against the wall and tilted forward. The doors swung open and office supplies crashed to the floor.

“What the fuck,” José yelped, dancing out of the way. He tripped on a cardboard box, stumbled over a chair, and fell to the floor, surrounded by ink pads, manila envelopes, and computer cords.

He ignored my help, pushed himself to his knees, and rifled through the debris.

His knife was missing, replaced in his right hand by a long eagle-feather ink stamp he had uncovered among the office supplies. A group project from days gone by, the stamp was made from a rectangle of rough-edged steel. I saw beside it a shallow ink pad encased in tin.

“Let’s do those changes you came up with, dawg. But hit me with this first.” José rubbed the rectangular stamp in black ink and handed it to me.

“Hit me!” He slapped his sinewy left shoulder, flexing. “Do it!”

I took a breath and jabbed the stamp home. When I pulled back, an eagle-feather tattoo appeared near the top of José’s shoulder.

“Now you, dawg,” he giggled, smothering the stamp in ink.

I rolled up my sleeve and flexed.

José took three giant steps backward. “Hang on. I’m gonna do this.”

He ran at me, the stamp cocked above his head, and brought it down on my shoulder, the sharp corner piercing my flesh.

I doubled over in pain. “What the hell!”

I pulled tentatively at the gash on my shoulder. My eagle feather was smeared, the black ink mingling with bright blood. It hurt, but I also felt relief as a red stream wound down my arm.

José beamed at his handiwork, and after a second of hesitation, we laughed together like maniacs.