Читать книгу Canoeing with Jose - Jon Lurie - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOLD HAL AND HAWK’S CANOE

The nights following this drama with José were stormy, with violent winds that lulled me to sleep the way unsettled weather always has. I didn’t hear much from him after the night he went after Sonic and crashed at my place, and I prayed that no news was good news.

In the meantime, I had decided that I was going to Hudson Bay, and José had agreed to join me. Planning for the expedition was still in the early stages when, on a morning that smelled like lightning and damp earth, I received a call from my friend Greeny, whom I had known since nursery school. He reported that a massive branch had fallen and smashed through my canoe, which was resting on sawhorses behind his house in Minneapolis.

I exhaled in a vaguely accusatory way. “Now what the hell am I going to paddle to Hudson Bay?”

I sped across the Lake Street bridge to his house on the other side of the Mississippi. The canoe, a 17-foot Royalex hull with ash seats, thwarts, and gunwales, had been with me since my sister Hawk gave it to me more than a decade earlier, when she moved to Colorado.

Growing up, Hawk was my idol. As a boy I shared a bedroom with my younger brother, Adam, but I preferred to sleep in Hawk’s room, on the floor beside her bed.

When I was 11 and Hawk was 13, she registered for a two-week session at a YMCA canoeing camp on West Bearskin Lake, along the Minnesota-Ontario border. I tagged along.

In subsequent years we camped with groups of kids our own age, but that first summer we went into the woods together. Sitting on a piney point on West Bearskin Lake, Hawk taught me how to smoke cigarettes and weed. She shared secrets that boys my age weren’t supposed to know, and showed me menstrual blood as it traveled down her leg following a midnight swim. Out on trail in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, she was always much tougher than me. She paddled harder and complained less about grueling portages, hunger, mosquitoes, and wet sleeping bags. I had always looked up to her, and the canoe she gave me had special meaning.

Greeny and I used handsaws to extricate the mangled boat from the leafy fist that had impaled it through the stern. When we yanked the offending branches from the hull, the gashes, two jagged wounds the size of apples, appeared to be terminal. Nearly certain that Hawk’s canoe would never float again, we gently loaded it onto my car.

I drove along River Road to downtown Saint Paul, and parked next to an unmarked loading dock behind an old brick warehouse. I climbed up a crumbling concrete lip and pounded on the garage door. Behind it I heard the proprietor of this underground repair shop bark impatiently, “Coming!”

Old Hal maintained no particular schedule, so I was thankful to find him at work. He opened the door and glared at me as if he were looking into the sun. The previous summer he had replaced the rotted gunwales on Hawk’s canoe, so I knew this was just his gruff way.

I wandered around the shop while Hal examined the canoe. There were three wood-strip canoes on the floor in various stages of completion. These were Hal’s projects, and they would eventually join the curvaceous masterpieces hanging on ropes from the ceiling. I couldn’t help but wonder if Hal was grouchy because his love of canoes and skill in building and repairing them had led to his imprisonment in a dusty warehouse just two blocks off the Mississippi River, which he rarely got to paddle.

I looked at a grainy color photograph on the wall. It was an image of a covered one-man canoe rigged with a sail, beached on the sandy shoreline of a large lake surrounded by pine trees.

“I designed that boat,” Hal offered half-heartedly. He went on to explain that the guy it belonged to had passed through Saint Paul recently. He was paddling from Patagonia to Alaska in stages.

“He came to me and asked for a canoe he could sail on the big waters up North,” Hal continued. “The guy takes winters off, but apart from those breaks he has been paddling constantly for four or five years.”

This seemed like a real achievement to me, but Hal quickly discredited the effort. “He’s a rich man and his kids are out of the house. He isn’t married. No pets. No one to take care of but himself. What the hell else does he have to do?”

I thought about what I had to do. I took care of my three daughters and my son four days and three nights a week. I was constantly struggling with my ex-wife for custody of the kids. I had to figure out what I was going to do now that my three-year graduate program at the University of Minnesota was nearing completion. And I had to get a job in order to begin to repay my $30,000 student loan.

“Once I’m finished with it, this canoe will take you anywhere you want to go,” Hal said.

“Even Hudson Bay?” I replied.

Hal’s eyes softened. He invited me back to his office, set down a blue plastic barrel of the sort used in Minnesota to distribute salt on the roads, and ordered me to sit. He described how he had paddled many venerable waterways, including Great Slave Lake, the Yukon River, and the Border Route from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods. The Sevareid route had always loomed above all others in his imagination, but he was getting too old to even think about it now. He offered me a grimy can of Diet Coke from the shelf above his computer.

“You’ll need a shotgun: double-barreled, 20-gauge minimum, pump action. Anything smaller will just piss off the bears,” he said. “The Canadians are insane about guns. They’ll make you fill out a pile of paperwork before they let you bring one into their country—and even then they’ll probably deny you entry.”

Hal interrupted himself, logging onto the Web site for the Canada Firearms Centre and printing out a one-page declaration form, along with two pages of instructions.

“And when that polar bear attacks,” Hal continued, as if it were inevitable, “you’re going to have to unload on him. Pump and unload, right in the skull.”

I couldn’t help but smile. I had never seen Hal emote, but the thought of fighting off a polar bear had him really worked up.

“I don’t care if that goddamn bear looks like a rug,” he went on. “You just reload and empty, again and again. You can’t be too careful. It’s your life or his.”

Hal calmed down slowly, then conceded that there “might not be bear issues,” but only if proper care was taken.

I described my strategy for keeping predators out of camp. “I always string my food pack out of reach, between two trees.”

“Suicide,” he cried out in response, shaking his bald skull and wagging a finger. “You can’t hang your food in the subarctic. The few trees on the tundra aren’t tall enough to hang food out of reach of a polar bear. You lose your food supply, you starve. You need to carry your food in one of these things.”

Hal pointed at the salt barrel I was seated on. Its thick plastic shell and metal locking ring would keep my food safe. He explained how a friend of his at the Department of Transportation had donated the barrels. Hal turned around and sold them to canoeists. He normally cleaned them up and charged $50 each, but he was offering to sell me two for that price, so long as I was willing to wash them myself.

When he was finished repairing Hawk’s canoe, Hal proclaimed nonchalantly, it would be more durable than it was before the accident. Just in case, however, and in light of the fact that there were plenty of treacherous rapids and nasty waterfalls up on the Hayes River—the leg of the Sevareid route running some 500 miles northwest from Lake Winnipeg—he offered to sell me a patch kit that could be deployed easily in the backcountry.

“It may not look pretty,” he explained, “but this stuff will firm up hard as nails over any puncture.” I promptly paid for the kit, and agreed to return for the salt barrels and Hawk’s canoe.

Ten days passed before Hal called to say that the canoe was “ready to paddle to the end of the Earth.” It was a time of intense negotiation. After battling my ex-wife for 50 percent custody, I was asking our kids to stay with their mother for at least a dozen weeks while I inched up the globe in a canoe, a notion that prompted considerable indignation. Our two youngest kids, 6-year-old Malcolm and 13-year-old Martha, protested with particular vehemence. Only Gemma, our second child, encouraged me to go.

I concocted a ridiculous itinerary in an effort to satisfy everyone. I would shove off from the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers on April 15, return to Saint Paul from southwestern Minnesota two weeks later for Gemma’s high school graduation, resume paddling for three weeks, and return home from the Canadian border for Martha’s 14th birthday. Then I would go back to the river for three weeks, return home from northern Manitoba for Malcolm’s 7th birthday, put in four more weeks on the river, and return home again on August 6, for Allison’s 18th birthday. Finally, I would return to northern Manitoba for the last weeks of the trip, which I hoped to finish before Malcolm’s first day of school, just after Labor Day.

When I described this plan to my old friend Kocher, hoping to find validation, he raised his eyebrows. “I don’t think you should leave from Minneapolis. José isn’t going to tolerate paddling upstream on the Minnesota River for three weeks. It will take you five days just to make Mankato, which is only an hour’s drive from here. What’s to stop him from calling one of his homies at that point and arranging for a pickup.”

I was irritated by this insight, but I also knew that Kocher was right. He and I had been on enough expeditions to understand the screaming agony long-distance canoeing produces in the mind and body, and the overwhelming impulse to quit. I had to get far enough away so that José wouldn’t have a lot of choices when he inevitably realized that paddling 35 to 40 miles a day was truly torturous.

Back at Midwest Canoe, Hal cleared paperwork from his desk and scribbled out my invoice. Then—after I had explained the situation with José, my insane itinerary, and my inability to come to terms with a starting point for the expedition—he set me straight. “You’re not Sevareid,” he spat. “You’re not some teenage kid with nothing else to do. Who are you anyway?”

When I told him I was a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, Hal unleashed a tirade on the state of modern literature. It was “self-indulgent,” he complained, and only reflected “the failure of our society to create original thinkers.” I was astonished that this grumpy man who built and repaired canoes was so passionate about literature.

Hal went on to explain that paddling the nearly 500-mile stretch from Lake Winnipeg to the sea on the Hayes River was “like climbing Mount Everest, except that far more people summit Everest every year than reach Hudson Bay on the Hayes. It’s the crown jewel of the canoeing world. The rest of Sevareid’s route, the 1500 miles leading to the Hayes, is really just a driveway to the north end of Lake Winnipeg.”

I confessed to Hal that I was unsure what the trip would accomplish if we didn’t start in Minneapolis and end at Hudson Bay, as Sevareid had done.

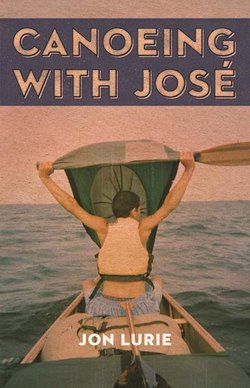

This was the most preposterous thing he had ever heard. “Why would you want to do what someone else has done? Totally unoriginal. Are you Eric Arnold Sevareid? For Christ’s sake, didn’t you say you were a writer? Take this Indian–Puerto Rican kid, this José, and make the journey your own. Canoeing with the Cree has already been written. Write your own story. Write Canoeing with José!”

Over the following days, I checked out nearly 20 topographical maps covering Sevareid’s entire route from an obscure campus library for geography majors. I took them home and pored over the charts, which were covered by blue veins of water and the green flesh of mother earth.

And then one afternoon, I dropped in to see José at Pawn Minnesota, as I had done almost every day since he agreed to come on the trip. Dressed in his freshly pressed uniform, a white shirt with narrow black tie, he bought and sold just about everything: hand tools, DVDs, video games, guitars, televisions, stereos, computers, MP3 players. My repeated visits provided opportunities to remind him about our impending departure, and to implore him to get a pair of glasses for the trip.

Nearly blind, José never noticed me until I was next in line at his counter.

“Good afternoon, sir,” José said professionally.

“Did you get the stuff yet?” I whispered confidentially. I had given him a list of items to acquire before the day planned for our departure.

Each time I asked he seemed surprised, and each time his reply was the same: “No, dawg, not yet. But I will.” It was unnerving to be putting so much energy into researching the route and acquiring gear, unsure if José was serious about going.

When I unrolled the maps for him later that night at my apartment, José seemed uninterested. He looked away and changed the subject. His older brother had been released from prison recently after having raped an adolescent cousin, and he and José had met two young women, wealthy members of one of Minnesota’s casino-rich Dakota tribes. They had moved in with these women, using them for their Escalades, condos, and booze. It was a cushy setup, and I feared José might never leave.

I pointed to the region north of Lake Winnipeg, where we would encounter treacherous white water and long stretches of wilderness. I also explained how we would have to be particularly mindful of polar bears.

“Oh, hell no, bro,” he cried, “I ain’t going into no polar bear territory. That ain’t even close to how I’m going out. You for reals?”

I assured him I was, and went to the computer to search polar bears. The first listing was a polar bear fact sheet. Up came a colorful page from Ranger Rick magazine, illustrated with endangered species from around the world: a mountain gorilla bared his teeth and pounded his chest, a komodo dragon swiped the air with its razor-sharp claw, and a massive polar bear stalked a field of snow and ice.

José leaped back from the screen and backed away to the far side of the living room, shouting, “Hell no. Hell no. I ain’t canoeing through no jungle with dragons and gorillas. Oh, fuck no. Are you insane, dawg? I ain’t going.”

I laughed aloud at the notion that these equatorial creatures would haunt our northern journey, then promised that there would be no gorillas or dragons, and that, in the unlikely event we were attacked by a polar bear, I would fill said predator with all the lead at my disposal. José seemed appeased for the most part, and we agreed again on the date of our departure, just a few days away.

Finally, the day before we were to set out, I left José in a van idling outside my ex-wife’s building in downtown Saint Paul and climbed the five flights to her apartment. The ink was still fresh on our divorce, and I dreaded every interaction with Jane. I was 20 and she 24 when we first met in a Native American studies class at the University of Minnesota. She was pretty and outgoing, I was lonely and increasingly estranged from my family. And I couldn’t help but fall in love with Jane’s two-year-old daughter, Allison. In that brief initial period of purity in our relationship, I committed to raising Allison, and it was this that had kept us together through a series of moves across Minnesota, Spain, South Dakota, Texas, and Alaska.

We had shared incredible intimacy in our marriage, but in recent years Jane and I had come to distrust each other. And now I resented her for hovering as I hugged the kids and said a silent prayer. Having long subdued my emotions in her presence, I said goodbye without shedding any tears. But I couldn’t help but linger at the door as Malcolm and Martha pleaded with their eyes for me to stay.