Читать книгу Proust Was a Neuroscientist - Jonah Lehrer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Emerson

ОглавлениеWhitman’s faith in the transcendental body was strongly influenced by the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson. When Whitman was still a struggling journalist living in Brooklyn, Emerson was beginning to write his lectures on nature. A lapsed Unitarian preacher, Emerson was more interested in the mystery of his own mind than in the preachings of some aloof God. He disliked organized religion because it relegated the spiritual to a place in the sky instead of seeing the spirit among “the common, low and familiar.”

Without Emerson’s mysticism, it is hard to imagine Whitman’s poetry. “I was simmering, simmering, simmering,” Whitman once said, “and Emerson brought me to a boil.” From Emerson, Whitman learned to trust his own experience, searching himself for intimations of the profound. But if the magnificence of Emerson was his vagueness, his defense of Nature with a capital N, the magnificence of Whitman was his immediacy. All of Whitman’s songs began with himself, nature as embodied by his own body.

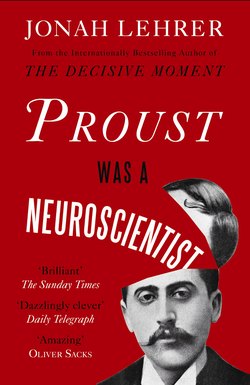

An engraving of Walt Whitman from July 1854. This imageserved as the frontispiece for the first edition of Leaves of Grass.

And while Whitman and Emerson shared a philosophy, they could not have been more different in person. Emerson looked like a Puritan minister, with abrupt cheekbones and a long, bony nose. A man of solitude, he was prone to bouts of selfless self-absorption. “I like the silent church before the service begins,” he confessed in “Self-Reliance.” He wrote in his journal that he liked man, but not men. When he wanted to think, he would take long walks by himself in the woods.

Whitman — “broad shouldered, rough-fleshed, Bacchus-browed, bearded like a satyr, and rank” — got his religion from Brooklyn, from its dusty streets and its cart drivers, its sea and its sailors, its mothers and its men. He was fascinated by people, these citizens of his sensual democracy. As his uncannily accurate phrenological exam put it,* “Leading traits of character appear to be Friendship, Sympathy, Sublimity and Self-Esteem, and markedly among his combinations the dangerous fault of Indolence, a tendency to the pleasure of Voluptuousness and Alimentiveness, and a certain reckless swing of animal will, too unmindful, probably, of the conviction of others.”

Whitman heard Emerson for the first time in 1842. Emerson was beginning his lecture tour, trying to promote his newly published Essays. Writing in the New York Aurora, Whitman called Emerson’s speech “one of the richest and most beautiful compositions” he had ever heard. Whitman was particularly entranced by Emerson’s plea for a new American poet, a versifier fit for democracy: “The poet stands among partial men for the complete man,” Emerson said. “He reattaches things to the whole.”

But Whitman wasn’t ready to become a poet. For the next decade, he continued to simmer, seeing New York as a journalist and as the editor of the Brooklyn Eagle and Freeman. He wrote articles about criminals and abolitionists, opera stars and the new Fulton ferry. When the Freeman folded, he traveled to New Orleans, where he saw slaves being sold on the auction block, “their bodies encased in metal chains.” He sailed up the Mississippi on a side-wheeler, and got a sense of the Western vastness, the way the “United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.”

It was during these difficult years when Whitman was an unemployed reporter that he first began writing fragments of poetry, scribbling down quatrains and rhymes in his cheap notebooks. With no audience but himself, Whitman was free to experiment. While every other poet was still counting syllables, Whitman was writing lines that were messy montages of present participles, body parts, and erotic metaphors. He abandoned strict meter, for he wanted his form to reflect nature, to express thoughts “so alive that they have an architecture of their own.” As Emerson had insisted years before, “Doubt not, O poet, but persist. Say ‘It is in me, and shall out.’”

And so, as his country was slowly breaking apart, Whitman invented a new poetics, a form of inexplicable strangeness. A self-conscious “language-maker,” Whitman had no precursor. No other poet in the history of the English language prepared readers for Whitman’s eccentric cadences (“sheath’d hooded sharp-tooth’d touch”), his invented verbs (“unloosing,” “preluding,” “unreeling”), his love of long anatomical lists,* and his honest refusal to be anything but himself, syllables be damned. Even his bad poetry is bad in a completely original way, for Whitman only ever imitated himself.

And yet, for all its incomprehensible originality, Whitman’s verse also bears the scars of his time. His love of political unions and physical unity, the holding together of antimonies: these themes find their source in America’s inexorable slide into the Civil War. “My book and the war are one,” Whitman once said. His notebook breaks into free verse for the first time in lines that try to unite the decade’s irreconcilables, the antagonisms of North and South, master and slave, body and soul. Only in his poetry could Whitman find the whole he was so desperately looking for:

I am the poet of the body

And I am the poet of the soul

I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters

And I will stand between the masters and the slaves,

Entering into both so that both shall understand me alike.

In 1855, after years of “idle versifying,” Whitman finally published his poetry. He collected his “leaves” — printing lingo for pages — of “grass” — what printers called compositions of little value — in a slim, cloth-bound volume, only ninety-five pages long. Whitman sent Emerson the first edition of his book. Emerson responded with a letter that some said Whitman carried around Brooklyn in his pocket for the rest of the summer. At the time, Whitman was an anonymous poet and Emerson a famous philosopher. His letter to Whitman is one of the most generous pieces of praise in the history of American literature. “Dear Sir,” Emerson began:

I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of “Leaves of Grass.” I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit & wisdom that America has yet contributed. I am very happy in reading it. It meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile & stingy nature, as if too much handiwork or too much lymph in the temperament were making our western wits fat & mean. I give you joy of your free & brave thought…. I greet you at the beginning of a great career.

Whitman, never one to hide a good review from “the Master,” sent Emerson’s private letter to the Tribune, where it was published and later included in the second edition of Leaves of Grass. But by 1860, Emerson had probably come to regret his literary endorsement. Whitman had added to Leaves of Grass the erotic sequence “Enfans d’Adam” (“Children of Adam”), a collection that included the poems “From Pent-up Aching Rivers,” “I Am He that Aches with Love,” and “O Hymen! O Hymenee!” Emerson wanted Whitman to remove the erotic poems from the new edition of his poetry. (Apparently, some parts of Nature still had to be censored.) Emerson made this clear while the two were taking a long walk across Boston Common, expressing his fear that Whitman was “in danger of being tangled up with the unfortunate heresy” of free love.

Whitman, though still an obscure poet, was adamant: “Enfans d’Adam” must remain. Such an excision, he said, would be like castration and “What does a man come to with his virility gone?” For Whitman, sex revealed the unity of our form, how the urges of the flesh became the feelings of the soul. He would remember in the last preface to Leaves of Grass, “A Backwards Glance over Traveled Roads,” that his conversation with Emerson had crystallized his poetic themes. Although he admitted that his poetry was “avowedly the song of sex and Amativeness and ever animality,” he believed that his art “lifted [these bodily allusions] into a different light and atmosphere.” Science and religion might see the body in terms of its shameful parts, but the poet, lover of the whole, knows that “the human body and soul must remain an entirety.” “That,” insisted Whitman, “is what I felt in my inmost brain and heart, when I only answer’d Emerson’s vehement arguments with silence, under the old elms of Boston Common.”

Despite his erotic epiphany, Whitman was upset by his walk with Emerson. Had no one understood his earlier poetry? Had no one seen its philosophy? The body is the soul. How many times had he written that? In how many different ways? And if the body is the soul, then how can the body be censored? As he wrote in “I Sing the Body Electric,” the central poem of “Enfans d’Adam”:

O my body! I dare not desert the likes of you in other men

and women, nor the likes of the parts of you,

I believe the likes of you are to stand or fall with the likes

of the soul, (and that they are the soul,)

I believe the likes of you shall stand or fall with my

Poems, and that they are my poems.

And so, against Emerson’s wishes, Whitman published “Enfans d’Adam.” As Emerson predicted, the poems were greeted with cries of indignation. One reviewer said “that quotations from the ‘Enfans d’Adam’ poems would be an offence against decency too gross to be tolerated.” But Whitman didn’t care. As usual, he wrote his own anonymous reviews. He knew that if his poetry were to last, it must leave nothing out. It must be candid, and it must be true.