Читать книгу Proust Was a Neuroscientist - Jonah Lehrer - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Social Physics

ОглавлениеIn Eliot’s time, that age of flowering rationality, the question of human freedom became the center of scientific debate. Positivism — a new brand of scientific philosophy founded by Auguste Comte — promised a utopia of reason, a world in which scientific principles perfected human existence. Just as the theological world of myths and rituals had given way to the philosophical world, so would philosophy be rendered obsolete by the experiment and the bell curve. At long last, nature would be deciphered.

The lure of positivism’s promises was hard to resist. The intelligentsia embraced its theories; statisticians became celebrities; everybody looked for something to measure. For the young Eliot, her mind always open to new ideas, positivism seemed like a creed whose time had come. One Sunday, she abruptly decided to stop attending church. God, she decided, was nothing more than fiction. Her new religion would be rational.

Like all religions, positivism purported to explain everything. From the history of the universe to the future of history, there was no question too immense to be solved. But the first question for the positivists, and in many ways the question that would be their undoing, was the paradox of free will. Inspired by Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity, which divined the cause of the elliptical motions found in the heavens, the positivists struggled to uncover a parallel order behind the motions of humans.* According to their depressing philosophy, we were nothing but life-size puppets pulled by invisible strings.

The founder of this “science of humanity” was Pierre-Simon Laplace. The most famous mathematician of his time, Laplace also served as Napoleon’s minister of the interior.† When Napoleon asked Laplace why there was not a single mention of God in his five-volume treatise on cosmic laws, Laplace replied that he “had no need of that particular hypothesis.” Laplace didn’t need God because he believed that probability theory, his peculiar invention, would solve every question worth asking, including the ancient mystery of human freedom.

Laplace got the idea for probability theory from his work on the orbits of planets. But he wasn’t nearly as interested in celestial mechanics as he was in human observation of those mechanics. Laplace knew that astronomical measurements rarely measured up to Newton’s laws. Instead of being clocklike, the sky described by astronomers was consistently inconsistent. Laplace, trusting the order of the heavens over the eye of man, believed this irregularity resulted from human error. He knew that two astronomers plotting the orbit of the same planet at the same time would differ reliably in their data. The fault was not in the stars, but in ourselves.

Laplace’s revelation was that these discrepancies could be defeated. The secret was to quantify the errors. All one had to do was plot the differences in observation and, using the recently invented bell curve, find the most probable observation. The planetary orbit could now be tracked. Statistics had conquered subjectivity.

But Laplace didn’t limit himself to the trajectory of Jupiter or the rotation of Venus. In his book Essai sur les Probabilités, Laplace attempted to apply the probability theory he had invented for astronomy to a wide range of other uncertainties. He wanted to show that the humanities could be “rationalized,” their ignorance resolved by the dispassionate logic of math. After all, the principles underlying celestial mechanics were no different than those underlying social mechanics. Just as an astronomer is able to predict the future movement of a planet, Laplace believed that before long humanity would be able to reliably predict its own behavior. It was all just a matter of computing the data. He called this brave new science “social physics.”

Laplace wasn’t only a brilliant mathematician; he was also an astute salesman. To demonstrate how his new brand of numerology would one day solve everything — including the future — Laplace invented a simple thought experiment. What if there were an imaginary being — he called it a “demon” — that “could know all the forces by which nature is animated”? According to Laplace, such a being would be omniscient. Since everything was merely matter, and matter obeyed a short list of cosmic laws (like gravity and inertia), knowing the laws meant knowing everything about everything. All you had to do was crank the equations and decipher the results. Man would finally see himself for “the automaton that he is.” Free will, like God, would become an illusion, and we would see that our lives are really as predictable as the planetary orbits. As Laplace wrote, “We must … imagine the present state of the universe as the effect of its prior state and as the cause of the state that will follow it. Freedom has no place here.”

But just as Laplace and his cohorts were grasping on to physics as the paragon of truth (since physics deciphered our ultimate laws), the physicists were discovering that reality was much more complicated than they had ever imagined. In 1852, the British physicist William Thomson elucidated the second law of thermodynamics. The universe, he declared, was destined for chaos. All matter was slowly becoming heat, decaying into a fevered entropy. According to Thomson’s laws of thermodynamics, the very error Laplace had tried to erase — the flaw of disorder — was actually our future.

James Clerk Maxwell, a Scottish physicist who discovered electromagnetism, the principles of color photography, and the kinetic theory of gases, elaborated on Thomson’s cosmic pessimism. Maxwell realized that Laplace’s omniscient demon actually violated the laws of physics. Since disorder was real (it was even increasing), science had fundamental limits. After all, pure entropy couldn’t be solved. No demon could know everything.

But Maxwell didn’t stop there. While Laplace believed that you could easily apply statistical laws to specific problems, Maxwell’s work with gases had taught him otherwise. While the temperature of a gas was wholly determined by the velocity of its atoms — the faster they fly, the hotter the gas — Maxwell realized that velocity was nothing but a statistical average. At any given instant, the individual atoms were actually moving at different speeds. In other words, all physical laws are only approximations. They cannot be applied with any real precision to particulars. This, of course, directly contradicted Laplace’s social physics, which assumed that the laws of science were universal and absolute. Just as a planet’s position could be deduced from the formula of its orbit, Laplace believed, our behaviors could be plotted in terms of our own ironclad forces. But Maxwell knew that every law had its flaw. Scientific theories were functional things, not perfect mirrors to reality. Social physics was founded on a fallacy.

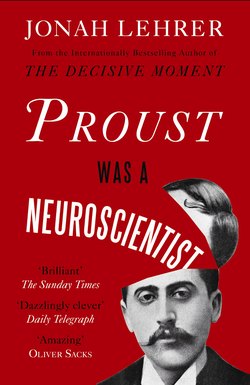

An etching of George Eliot in 1865 by Paul Adolphe Rajon, after the drawing by Sir Frederick William Burton