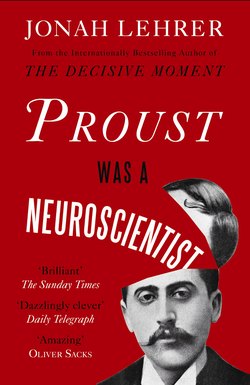

Читать книгу Proust Was a Neuroscientist - Jonah Lehrer - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Walt Whitman

ОглавлениеThe Substance of Feeling

The poet writes the history of his own body.

— Henry David Thoreau

FOR WALT WHITMAN, the Civil War was about the body. The crime of the Confederacy, Whitman believed, was treating blacks as nothing but flesh, selling them and buying them like pieces of meat. Whitman’s revelation, which he had for the first time at a New Orleans slave auction, was that body and mind are inseparable. To whip a man’s body was to whip a man’s soul.

This is Whitman’s central poetic idea. We do not have a body, we are a body. Although our feelings feel immaterial, they actually begin in the flesh. Whitman introduces his only book of poems, Leaves of Grass, by imbuing his skin with his spirit, “the aroma of my armpits finer than prayer”:

Was somebody asking to see the soul?

See, your own shape and countenance …

Behold, the body includes and is the meaning, the main

Concern, and includes and is the soul

Whitman’s fusion of body and soul was a revolutionary idea, as radical in concept as his free-verse form. At the time, scientists believed that our feelings came from the brain and that the body was just a lump of inert matter. But Whitman believed that our mind depended upon the flesh. He was determined to write poems about our “form complete.”

This is what makes his poetry so urgent: the attempt to wring “beauty out of sweat,” the metaphysical soul out of fat and skin. Instead of dividing the world into dualisms, as philosophers had done for centuries, Whitman saw everything as continuous with everything else. For him, the body and the soul, the profane and the profound, were only different names for the same thing. As Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Boston Transcendentalist, once declared, “Whitman is a remarkable mixture of the Bhagvat Ghita and the New York Herald.”

Whitman got this theory of bodily feelings from his investigations of himself. All Whitman wanted to do in Leaves of Grass was put “a person, a human being (myself, in the later half of the Nineteenth Century, in America) freely, fully and truly on record.” And so the poet turned himself into an empiricist, a lyricist of his own experience. As Whitman wrote in the preface to Leaves of Grass, “You shall stand by my side to look in the mirror with me.”

It was this method that led Whitman to see the soul and body as inextricably “interwetted.” He was the first poet to write poems in which the flesh was not a stranger. Instead, in Whitman’s unmetered form, the landscape of his body became the inspiration for his poetry. Every line he ever wrote ached with the urges of his anatomy, with its wise desires and inarticulate sympathies. Ashamed of nothing, Whitman left nothing out. “Your very flesh,” he promised his readers, “shall be a great poem.”

Neuroscience now knows that Whitman’s poetry spoke the truth: emotions are generated by the body. Ephemeral as they seem, our feelings are actually rooted in the movements of our muscles and the palpitations of our insides. Furthermore, these material feelings are an essential element of the thinking process. As the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio notes, “The mind is embodied … not just embrained.”

At the time, however, Whitman’s idea was seen as both erotic and audacious. His poetry was denounced as a “pornographic utterance,” and concerned citizens called for its censorship. Whitman enjoyed the controversy. Nothing pleased him more than dismantling prissy Victorian mores and inverting the known facts of science.

The story of the brain’s separation from the body begins with René Descartes. The most influential philosopher of the seventeenth century, Descartes divided being into two distinct substances: a holy soul and a mortal carcass. The soul was the source of reason, science, and everything nice. Our flesh, on the other hand, was “clock-like,” just a machine that bleeds. With this schism, Descartes condemned the body to a life of subservience, a power plant for the brain’s light bulbs.

In Whitman’s own time, the Cartesian impulse to worship the brain and ignore the body gave rise to the new “science” of phrenology. Begun by Franz Josef Gall at the start of the nineteenth century, phrenologists believed that the shape of the skull, its strange hills and hollows, accurately reflected the mind inside. By measuring the bumps of bone, these pseudoscientists hoped to measure the subject’s character by determining which areas of the brain were swollen with use and which were shriveled with neglect. Our cranial packaging revealed our insides; the rest of the body was irrelevant.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the promise of phrenology seemed about to be fulfilled. Innumerable medical treatises, dense with technical illustrations, were written to defend its theories. Endless numbers of skulls were quantified. Twenty-seven different mental talents were uncovered. The first scientific theory of mind seemed destined to be the last.

But measurement is always imperfect, and explanations are easy to invent. Phrenology’s evidence, though amassed in a spirit of seriousness and sincerity, was actually a collection of accidental observations. (The brain is so complicated an organ that its fissures can justify almost any imaginative hypothesis, at least until a better hypothesis comes along.) For example, Gall located the trait of ideality in “the temporal ridge of the frontal bones” because busts of Homer revealed a swelling there and because poets when writing tend to touch that part of the head. This was his data.

Of course, phrenology strikes our modern sensibilities as woe-fully unscientific, like an astrology of the brain. It is hard to imagine its allure or comprehend how it endured for most of the nineteenth century.* Whitman used to quote Oliver Wendell Holmes on the subject: “You might as easily tell how much money is in a safe feeling the knob on the door as tell how much brain a man has by feeling the bumps on his head.” But knowledge emerges from the litter of our mistakes, and just as alchemy led to chemistry, so did the failure of phrenology lead science to study the brain itself and not just its calcified casing.

Whitman, a devoted student of the science of his day,† had a complicated relationship with phrenology. He called the first phrenology lecture he attended “the greatest conglomeration of pretension and absurdity it has ever been our lot to listen to…. We do not mean to assert that there is no truth whatsoever in phrenology, but we do say that its claims to confidence, as set forth by Mr. Fowler, are preposterous to the last degree.” More than a decade later, however, that same Mr. Fowler, of the publishing house Fowler and Wells in Manhattan, became the sole distributor of the first edition of Leaves of Grass. Whitman couldn’t find anyone else to publish his poems. And while Whitman seems to have moderated his views on the foolishness of phrenology — even going so far as to undergo a few phrenological exams himself* — his poetry stubbornly denied phrenology’s most basic premise. Like Descartes, phrenologists looked for the soul solely in the head, desperate to reduce the mind to its cranial causes. Whitman realized that such reductions were based on a stark error. By ignoring the subtleties of his body, these scientists could not possibly account for the subtleties of his soul. Like Leaves of Grass, which could only be understood in “its totality — its massings,” Whitman believed that his existence could be “comprehended at no time by its parts, at all times by its unity.” This is the moral of Whitman’s poetic sprawl: the human being is an irreducible whole. Body and soul are emulsified into each other. “To be in any form, what is that?” Whitman once asked. “Mine is no callous shell.”