Читать книгу My Dear Ones: One Family and the Final Solution - Jonathan Wittenberg, Jonathan Wittenberg - Страница 10

3: THE ROOTS OF A RABBINICAL FAMILY

ОглавлениеThe first time I explored the old Jewish Quarter in Kraków was at night, walking along Szeroka Street past the Remu Synagogue, losing my way in small alleyways to find myself at the back of the ancient cemetery, staring through the railings at the worn gravestones of generations of scholars of Torah. I searched for the marks in the entranceways to courtyards and houses where the mezuzot, cases containing the tiny roll of parchment inscribed with the injunction to write on the doorposts of every home the command to love the Lord your God, had once been affixed. In my mind was the picture taken in secret by Roman Vishniac in the late 1930s of an old Jew studying Kabbalah by candlelight. Not long afterwards he, his world and virtually all its inhabitants were destroyed. Yet I imagined I might somehow encounter his spirit, together with the souls of those who had for generations devoted themselves to the love of Torah, among these places of prayer and learning, now empty of the Jews who had imbued them with their yearning and devotion.

I had also noticed the sign above an unobtrusive entrance in Jozefa Street: Kove’a Ittim LaTorah (‘establish fixed times for Torah’), a name taken from the Talmudic dictum that every Jew must fix regular hours of the day and night for learning Torah. The building had once been a Yeshivah, a school for the intensive study of the classic Jewish texts and teachings. But I had no idea that there was any family connection. Here, however, was where my great-great-great-grandfather, head of the Rabbinical Court of Kraków, had taught his students Torah every day.

Among his children were Avraham Chaim Freimann, who would become the father of my great-grandfather, and Yisrael Meir Freimann, who was to be the father of my great-grandmother. Avraham Chaim remained as a rabbi and teacher of Torah in Kraków. After learning intensively among the greatest Torah scholars in Hungary, Yisrael Meir studied philosophy and oriental languages, receiving his doctorate from the University of Jena in 1860. He was called to the rabbinate of the beautiful old town of Filehne in the district of Posen in the same year. Also in that year he married Helene, the third daughter of the famed teacher Rabbi Yacob Ettlinger of Altona. When Steffi died and before it emerged that there was a plot available close to her sister on the Mount of Olives, I had been advised to tell the Burial Society that she was his great-great-granddaughter; such ancestry, even after four generations, would encourage them to accord her a place of honour in the ancient cemetery.

A single surviving photograph of Helene shows her to have been a beautiful and dignified lady; she was popular and much loved in the family. My great-grandmother Regina was born in Filehne on 12 January 1869. She was still a small child when the family moved to the nearby town of Ostrowo where, after a unanimous election, Yisrael Meir was appointed rabbi, serving there until his death. He was held in such esteem not only by the Jews but by the entire local population that in 1900, over fifteen years after he died, a street was named Freimannstrasse in his honour.

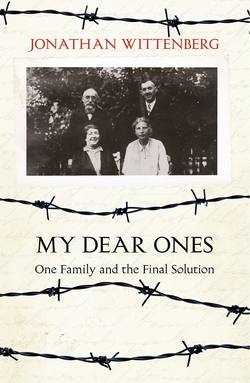

Rabbi Yisrael Meir Freimann and his wife Helene.

My great-grandfather Jacob was born in Kraków to Avraham Chaim and his second wife Sophie on 1 October 1866, Shemini Atzeret, the conclusion of the harvest festival. Jacob grew up in the heart of the culture of intense and assiduous devotion to traditional Talmudic study which characterised much of the Jewish world of Eastern and Central Europe in the mid-nineteenth century. Among his teachers were the greatest analysts of Talmud and Jewish law of their generation. ‘The boy received from his father the foundations of his Jewish education, that girsa deyankuta, that ineradicable childhood understanding of the Rabbinic-Talmudic way of life and thought,’ wrote the editor of the Festschrift, the collection of scholarly essays presented to him as a tribute on his seventieth birthday.1

Jacob lost his parents at a young age; his mother Sophie died of typhoid fever in 1875 when he was only nine, and his father Avraham Chaim of cholera in 1882. I had visited the old cemetery, stopping by the burial places of the famous sixteenth-century scholar and legalist Rabbi Moses Isserles, before wandering off the trodden pathways into the grass to try to decipher the Hebrew inscriptions on the worn-down sandstone of the graves of the less illustrious dead. But in fact my great-grandfather’s parents, Rabbi Avraham Chaim Freimann and his wife Sophie were not here. They were buried in the so-called ‘new’ cemetery, which was destroyed by the Nazis who used the gravestones to pave the nearby concentration camp of Plashov. After the war, when an attempt was made to restore them to their proper location, the family tried to find the headstones, but to no avail.

Jacob’s brothers and sisters went to live with their uncle in America, a decision which would later help save the lives of part of the family trapped in Europe. A different existence beckoned to them in the new world. But Jacob preferred to remain within the trusted ambience of an intensely Jewish culture rooted in love and boundless dedication to Torah. He therefore chose to travel to his uncle Rabbi Israel Meir in Ostrowo, under whose direction he would be able to continue his studies.

Before leaving Kraków, Jacob, who was only sixteen when he was orphaned, noted down the inscriptions on his parents’ graves in his beautiful cursive Hebrew script:

My mother:

in the midst of her days died a most honoured lady,

young children seven she left behind;

all who knew and cared for her wept and mourned …

My father:

here lies a most precious man

who walked in the path of the perfect-hearted.

In this manner he carried his parents’ characters and culture with him for the rest of his life.

Jacob had already earned a reputation as a matmid, a scholar devoted day and night to Torah. He took to Ostrowo a letter from some of the most famous teachers of the generation, testifying that he had ‘an understanding heart to attend to and comprehend his studies’.

In his uncle’s house Jacob completed his schooling and pursued his Talmudic education. Here, too, he met his future wife, his first cousin Regina. He would have been drawn to her not only on account of her personality, but because of the rich ambience of Jewish living and learning in which they had both been raised. Reflecting on God’s promise to Adam that he would make him a fitting helpmeet, Jacob noted that ‘whoever considers the upbringing of the woman he wants to marry, the education she received from her parents and the merits of the previous generations of her family, chooses well.’2

By the time he enrolled in the University of Berlin at the age of twenty, he was already in possession of a Hatarat Hora’ah, a diploma recognising him as an authoritative teacher of rabbinic Judaism. Since the middle of the nineteenth century traditional Jewry in the German lands had been influenced decisively by the philosophy of Samson Raphael Hirsch with its slogan of ‘Torah together with the way of the world’, combining unwavering adherence to Jewish law and ritual with full participation in the life and concerns of the culture and society in which one lived. For almost the first time in the long Jewish experience of exile it was possible to be a Yisroelmensch, a faithful Jew and a full citizen of one’s country, equal among others. This outlook became a cornerstone of German-Jewish Orthodoxy. It was partly also a response to the attrition suffered by the traditional community when, with the attainment of increasing civil rights through the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, German cultured society and its professions became accessible to Jews, many of whom aspired to its ways and were assimilated within its ranks. Hirsch’s philosophy was embodied in the educational principles of Ezriel Hildesheimer, in whose name a seminary was established in Berlin for the training of orthodox rabbis. It was here that Jacob Freimann came to study. He also took courses at the university; the German authorities required religious leaders in official positions and thus salaried by the state to possess a university education to doctoral level. Freimann followed courses in literature, oriental studies and philosophy before writing his thesis at the University of Tübingen on a Syriac translation of the Book of Daniel.

On 5 February 1891, equipped with his doctorate and his Semichah, his rabbinic ordination, he married his cousin Regina Freimann in her home town of Ostrowo. Her father had meanwhile died, but her mother, Helene, would live to be a much-loved grandparent. The marriage was close, respectful and happy. In a comment on the verse from Genesis, ‘It is not good for a man to be alone’, Rabbi Jacob noted the Talmud’s observation: ‘If your wife is low and gentle, bend down and seek her counsel in domestic matters.’ Photographs show that Regina was indeed considerably shorter than her husband, and she was certainly gentle in spirit. By ‘domestic matters’ a patronising confinement of the woman’s role to the kitchen was not meant, but rather the spirit and values of the home and what it represented, the heart and kernel of the Freimann couple’s life. One sensed that they were rarely, if ever, geographically, intellectually or spiritually apart.

After a brief period in Kanitz they settled in Holleschau with their two small daughters, Sophie, their eldest child, and Ella, who would become my grandmother. Soon after their arrival, on 3 September 1893 a new synagogue was dedicated. I was proudly shown the list of dignitaries in attendance; Rabbi Freimann’s signature appeared in the middle and it was he who conducted the opening ceremony. Sadly, the building was not destined to reach its half-century; it was burnt down by the Germans in 1941.

Not long after the dedication, a new house was constructed for the rabbi and his family. A graceful building, it stood opposite the synagogue, separated only by a vegetable garden. Ernst remembered it warmly:

It had eight rooms. In one of them the roof could be lifted up by springs and was used as our Sukka [the booth roofed with branches in which the harvest festival is celebrated]. Between this house and the synagogue was a garden with flowers and a part with vegetables. In the back was a shed for wood and coal, and for chickens, turkeys and ducks, a coop for the geese, and a laundry room. There were also trees: one plum tree, one pear tree, and one ‘Reine Claude’, a kind of plum. There were two toilets, a cellar and an attic.3

Water was drawn daily by the maid from a well near the entrance to the house and stored in a large covered barrel. The surrounding lands were fertile; local farmers came to the market to sell poultry, vegetables and fruit. In a letter to her mother in the summer of 1938 Sophie referred to the cherries, blueberries, blackberries, raspberries and damsons that she had bottled or turned into jam.

But life in Moravia was by no means always easy for Jews, as Jacob Freimann recorded in his history of the town. The community was probably first formed after it was driven out of nearby Olmütz in 1454. By the seventeenth century it was thriving, but the congregation had constantly to renew its privileges, as the local rulers kept changing. A document from 1631 listed the conditions under which it was tolerated: Jews were permitted to maintain a school, synagogue, hospital, ritual baths, cemetery and houses. They were allowed to practise their ceremonies and pursue their trade in cloth, wool, leather and linens. In return they had to provide the duke and a large number of lesser dignitaries with numerous gifts, anything from geese for Christmas to sugar, pepper, saffron and spices. In 1899 a blood libel led to pogroms across the Czech lands; in Holleschau hundreds of people went on the rampage, invading the Jewish quarter and robbing the houses, creating a challenging crisis for the still young and relatively inexperienced rabbi. It wasn’t until the birth of Czechoslovakia in 1919 as an independent nation that the autonomous Jewish community, effectively a twin settlement existing in parallel to the Christian town, merged with it into one civic entity.

These were good years for Rabbi Jacob and his wife. It was here that their third daughter Wally was born in 1894. Ernst, the first boy, followed in 1897, Trude in 1898, and their youngest child, Alfred, in 1899. The rabbi was able to find time to follow both his professional duties and his academic pursuits. He had a deep interest in history and became an important contributor to the work of Mekitsei Nirdamim, an international society devoted to the publication of scholarly editions of classic Jewish texts. He was appointed inspector of religion for the Jewish schools of northern Moravia and became chairman of the union of rabbis of Moravia and Silesia. It was in this capacity that he received a telegram from the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef in 1906 thanking him for the ‘patriotic tribute’ he had offered on behalf of his colleagues, though it was not clear what the occasion was on which he had contributed these congenial greetings.

Rabbi Jacob Freimann teaching in the synagogue.

In 1914 Jacob Freimann was called to the rabbinic seat of Posen, made famous by his illustrious predecessor Rabbi Akiva Eger. Twenty years later, in an accolade on his seventieth birthday, an admirer described his life there:

… his outstanding diplomatic skills, and above all the exemplary and deeply Jewish rabbinical home, run with tact and dedication by his life’s partner, created the atmosphere of his rabbinic incumbency. Then came the war years; it was necessary to look after wounded soldiers, prisoners of war and brothers in occupied lands. More than ever before, the troubles which afflicted the surrounding communities with their rich Jewish life poured into Posen. All important legal and political issues came before the Posen rabbinate for resolution.

When Posen became part of Poland as a result of the Treaty of Versailles following Germany’s defeat in the First World War, most of the city’s Jews, who spoke German, identified with German culture, and who felt threatened by the rising anti-Semitic tones of Polish nationalism backed by major elements of the Catholic Church, left to live in the Reich. However, Jacob and Regina remained until 1928, when they eventually moved to Berlin after he was offered the position of rabbi of the city’s oldest synagogue in the Heidereuterstrasse. ‘The Nazis destroyed it; there’s nothing left of it,’ my father told me. Nevertheless I went to visit the site where it had once stood. My father was correct; all that remained was a plaque noting that this had been the first of Berlin’s many synagogues: ‘Consecrated in 1714, the last service was held here in 1942, before the building was destroyed in 1945.’

Though he was sixty-two when he came to Berlin, Rabbi Freimann’s energies were in no way depleted. He taught history, literature, and practical rabbinics at the Hildesheimer Seminary where he himself had studied forty years earlier. He was appointed Av Bet Din, head of the rabbinical court. His reputation and authority extended well beyond the city, and beyond Germany itself; questions of Jewish law and scholarship were sent to him for his opinion from all over the world.

The early years in Berlin should have been a period of profound satisfaction for Jacob and Regina. Their six children were well settled in their lives; they were all married and their sons and sons-in-law were successful at their occupations. Their eldest daughter, Sophie, had remained in Holleschau where she had married Josef Redlich, grandson of the town’s former rabbi, whose family had been manufacturers of spirits for two generations. According to one account they possessed a rum distillery. But it seems more likely that they produced a variety of liquors. They were wealthy, but, after almost two decades of marriage, not blessed with children. They felt deeply at home in Czechoslovakia and had a wide circle of clients and friends across the neighbouring towns and villages. Trude had stayed in Poznań where she married Alex Peiser, a doctor at the city’s Jewish hospital; they had one child, Arnold, born in 1928. Jacob and Regina’s older son Ernst had studied medicine and, after serving in the Austro-Hungarian Army for the duration of the First World War, settled in Frankfurt, the city with Germany’s second largest, but oldest and most famous, Jewish community. Despite his professional obligations he was an ardent student of Judaism; in his memoirs he carefully recorded the names of all the major scholars and teachers with whom he had learnt Torah in every city in which he had lived. He had married Eva Heckscher, the daughter of a banker from Hamburg, and they soon had a thriving young family. The youngest of Jacob and Regina’s six children, Alfred, had completed his studies and was shortly to be appointed to the judiciary in Königsberg. Although it had been the city of Kant, it wasn’t renowned for its Jewish community, but the government had posted him there and events were soon to prove that the move to East Prussia was beschert (ordained in heaven) – as the Yiddish term succinctly put it. For it was here that he would meet his future wife. Wally too was married, to an eminent doctor; he had a passion for song- birds which, to the horror of other members of the family, he allowed to flap freely around their home. Wally was the only one of the six siblings later to be divorced. Sadly, she had no children. I remember visiting her when she was an old lady, a wizened figure who made a living by administering injections, existing in rather Spartan style in a flat on King George Street in the centre of Jerusalem. In fact, she had really wanted to become a doctor but because at the time women were apparently not allowed to study medicine, she had to settle for being a nurse instead. She was a brilliant cook. I stayed with her on my first ever visit to Israel when the somewhat grim asceticism of her manner rather frightened me. I never met her at her best or had the opportunity to appreciate the person she really was.

Ella and Robert Wittenberg, my grandparents, had initially settled in the small town of Rawitsch, where my grandfather owned a timber mill. My father once showed me a picture taken after the war, possibly as late as the early 1960s. The name Wittenberg was still displayed in large letters on a board by the entrance; nobody had thought it necessary to take it down. Evidently the possibility that any members of the family might one day return was too remote to merit consideration. After he died I searched every folder of my father’s papers but was not able to recover that photograph. My father was born in Rawitsch in 1921; two years later the family moved to nearby Breslau. My father would have been too young to understand but the move was probably occasioned by the election of a nationalist mayor, Kazimierz Czyszewski, in 1922. The Polish Nationalist Party was notoriously anti-Semitic. The Jews of Rawitsch suffered discrimination and persecution, including the refusal to hand them the keys to the synagogue. In October 1923 the Jewish community of Rawitsch was formally dissolved and its properties made over to the State Treasury.

Ella and Robert Wittenberg, my grandparents.

Breslau, a beautiful city on the Oder, had a substantial Jewish population and a famous rabbinical seminary named after the nineteenth-century founder of Conservative Judaism, Zecharias Frankel. I visited the town in 2010 for the rededication of its best-known synagogue, Zum Weissen Storch (At the White Stork). I wasn’t even able to look for ghosts; my father had never told me where they lived or what synagogue they had attended. I only knew that he had been a pupil at the Jewish school; a small photograph showed a rather bare and miserable playground. It was there that he and his classmates used to play football whenever their Jewish studies teacher was called to the phone in the middle of the lesson, according to my father a rather frequent occurrence. He vividly remembered how those boys too slow to return to their seats on time would be lifted back through the window by their ears. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘It did hurt.’ The family had been prosperous. ‘At midnight we would break for a large meal, with goose fat,’ my father said, remembering how they had honoured the custom of studying Torah all night on the festival of the Giving of the Law. ‘My mother’s recipes would say “Take twenty eggs,” he recalled, listening to my brother or me as we read out the more modest list of ingredients for a cake from some new-fangled, cholesterol-conscious work. ‘Who would dream of doing that today?’

It appeared too that the Wittenberg parents rather spoiled their children, as the disapproving tone of a letter from Sophie to Alfred in September 1937 indicated:

The Wittenbergs are finally on their way to join you [in Palestine]. Hopefully they’ll all soon find occupations. It’s particularly important for the children so that they can finally understand the seriousness of their situation. For the money they spent on their stay in Basel they could have lived for half a year. Sadly, Robert and Ella don’t seem to be very firm with the children and indulge them in things which don’t suit with their situation, like excursions, bike riding and so forth, instead of mending clothes, ironing and such like.

I remember my father telling me that after fleeing Breslau they had indeed gone to stay with relatives in Switzerland while waiting for their visas to come through, no doubt so as to be out of the way of the Gestapo. But nothing about my father suggested a spoilt childhood.

In 1936 Jacob Freimann marked his seventieth birthday; Alfred was already in Palestine, but no doubt the rest of the family gathered in Berlin for the occasion. It was the end of the summer during which the city had hosted the Olympic Games. Hitler had been at pains to show the world only the positive face of Germany; there had even been a brief reprieve in the more public measures against Jews. For the Freimann family, this would prove to be the last ever major celebration. The rabbi’s colleagues prepared a Jubilee volume in his honour; a family friend, Harry Levy, wrote the foreword:

Alongside an inherited rabbinical bearing, he possessed an even temperament, a psychological gift for empathy and relating to people, and most of all a flexibility of spirit which had its roots in the natural piety of a secure personality, as well as a powerful measure of common sense and understanding which matured increasingly over the years into wisdom. Added to that, he was equally well rooted in two almost diametrically opposed worlds, the eastern world of the Talmud, where he rejoiced in the minutiae of its argumentation, and the scholarly culture of Western Europe. Only such an inner harmony could render the sheer quantity of his achievements comprehensible.

In that suitcase in Jerusalem had been letters of tribute from colleagues and institutions of learning all around the world. One was even written on parchment. The event was to prove the crowning acknowledgement of his life’s work.

A little over a year later Jacob Freimann was dead. The Israelitisches Familienblatt carried a gracious obituary:

Others are noted and respected for their knowledge and learning, but he was loved by all who were privileged to draw close to him for his human qualities first and foremost, for his simplicity, his nobility of character, his inability to do anything unjust, his love of fairness and truth. It wasn’t at the pulpit, nor in his writings, nor at meetings that Jacob Freimann was most completely himself; he was truly himself in his own home which was as simple as he was, when he guided a small circle of people through the teachings of Judaism.

Though she was not mentioned directly, the words were clearly also an acknowledgement of his indebtedness to his wife. But no tribute is ever as honest, or as meaningful, as that of a person’s own children. Fifty years later, when he himself was in his eighties, Ernst made no distinction between his parents when he wrote about their values and their way of life:

It is hard for me to describe the unique characters of my parents. They were both meticulous in preserving the Jewish way of life in all its fine details. At the same time they showed tolerance towards all people, even those far from keeping the commandments. They were full of love for their children. They were very generous to the poor who came to their door; most of whom were given food to eat. They succeeded in helping to resolve the problems faced by many people in all their different aspects.

In a sermon dated 1929 on the opening chapter of Genesis, Rabbi Freimann noted:

Scripture tells us that ‘God saw that [creation] was good’ with the sole exception of man … All other creatures have just the one sole option – to remain at the level on which they were created and behave according to their inborn nature. To man alone is given the capacity for choice, the possibility of determining the course of his life according to his own free will. To man alone the task is granted of aspiring to perfection, of diligently devoting all the days of his life to its attainment.

A few lines further on he considered God’s famous question to Adam after he had eaten from the tree of knowledge:

‘God called out and said to the man, “Where are you?”’ This is no mere enquiry about his physical location but an expression of surprise and admonition: ‘See to where you have come by forsaking the path along which I commanded you to walk!’

He died before the depths to which that abandonment could lead were revealed in the destinies of his widow and their children.