Читать книгу My Dear Ones: One Family and the Final Solution - Jonathan Wittenberg, Jonathan Wittenberg - Страница 8

1: THE GRAVESTONE AND THE TRUNK

ОглавлениеMy father’s family had felt at home in Germany. They were leaders in the highly cultured world of German Jewry. They fought on the German side in the First World War; my grandfather’s brother was welcomed home to great acclaim as a hero twice-wounded. They spoke German, wrote in German and baked kosher cakes according to German recipes. ‘You have good family connections,’ my father told me. His mother’s father was a world-famous authority on Jewish law, from a dynasty of rabbis.

In 1945 all that was left of my father’s family in Europe were scattered ashes, one grave, their former homes, of which the surviving members were never able to regain possession, and memories. ‘So that you will know where to look for us afterwards,’ his aunt Sophie had written in a final letter informing her brother of her impending deportation. But in her case, and that of her sister Trude and their families, there was no one left for their relatives to find.

‘At first they did it all within the sanction of legality,’ my father used to say. Step by step, in small measures which initially sometimes showed little of outright violence, the Nazis and their supporters removed the Jewish populations in their midst from their positions, hemmed them in with restrictions, laid claim to their belongings, stripped them of their savings, dispossessed them of their homes, isolated them from those they loved, starved and tortured them, robbed them of their lives and turned them into ashes.

Of course I knew as I was growing up that my father’s family had come from Germany and that they had fled when he was in his teens. But I didn’t understand about his part of the family in the same way as I knew the story on my mother’s side. Her parents, also refugees from Germany, lived around the corner and I saw them several times each week. My father’s relatives resided in faraway Jerusalem; his father had died even before my older brother was born, and I had met his mother only two or three times, on her occasional trips to London. She had struck me as generous, gentle and kind, but quiet and self-contained. It never occurred to me, a teenager absorbed in my own life, that it could be important to traverse her quietness and listen to who she was. She used to send us big wooden cases of oranges or grapefruits, an exciting treat from an Israel which I had never yet visited.

I knew, but I didn’t really know; perhaps it would be more honest to say that I didn’t pay sufficient attention or care. There are many things of which one is aware, but only at the periphery of the mind. They never properly penetrate the consciousness, but hover like a distant landscape beyond the parameters of one’s immediate concerns. It doesn’t occur to one to ask the important questions; nothing provokes one to enquire. Only after it is too late is one overcome by a compelling urgency, and in retrospect the failure to have shown sufficient curiosity while there was still time seems as inexplicable as it feels inexcusable: why did I never trouble to ask, before those who could have answered were all dead?

But my brother and I grew up safe in England, a long way away from the past, too far to be minded to put the difficult questions while those who could have responded to them were still alive.

I remember one occasion when my father was in the scullery; I was in the kitchen rehearsing the script for the school assembly which was to be led the next day by the A level German set to which I belonged. It included a mocking comment about the Nazis. ‘Don’t forget that Hitler murdered millions of people,’ my father, who wasn’t in the habit of intervening, quietly observed. ‘He turned thousands of them into bars of soap, including several of your relatives. Don’t ever have anything to do with anyone who makes light of it, even in a joke.’ I felt instantly ashamed.

A few years before he died, my father instructed me to make a record of all the family members who had perished in the Holocaust and Israel’s wars. He carefully dictated their names in the vernacular and Hebrew, including the patronymic by which a person is referred to in formal Jewish documents. Slowly I typed them out, creating a testament which, following his wishes, I placed on the table every year on the bleak fast of the Ninth of Av, the date on which the Jewish people remembers its martyrs, and on the atonement fast of Yom Kippur. Then I would light a memorial candle and often, after coming home from the synagogue, sit and watch it flicker in the darkness, briefly illuminating the names, the walls and the small Ark containing the Torah scroll rescued by his family from the devastation. It was when he gave me that list that I understood for the first time the relationships between him and those people whom I had heard mentioned, though only infrequently and in passing, but never properly located on my internal family tree, his aunts Sophie and Trude and their families, his uncle Alfred, his grandmother Regina. It was then too that I began to realise quite how many of his family had perished and to ask myself what this must have meant to him and where in his heart he stored the sorrows of so much loss.

By then I understood his family better. I had stayed many times with his sisters Hella and Steffi in Jerusalem. There had been a third sister too, Eva, who had died very young, during the war. ‘She had leukaemia. The doctor said, “She needs red wine and chicken.” We can afford them now, but at that time in Palestine we had no money for such things. Who did?’ I’m not sure my father ever showed me her picture. But she was more important to him than the paucity of his references suggested and in his final illness he would often call out, ‘Eva, Eva, help me,’ raising his arms and stretching out his bent hands as if his long-dead sister would reach down and raise him from his sickbed. It struck me as I listened to his semi-conscious pleading that the two of them must have been closer companions in those impoverished years in Palestine than he had previously allowed anyone to perceive.

I learnt equally little from my father about his grandmother Regina. From time to time he would refer to the famous rabbinic lineage to which the Freimann side of the family belonged. Regina had been married to the distinguished rabbi Jacob Freimann, of whom I had sometimes heard my father speak with deep respect and quiet pride. But that was virtually all I knew.

My father’s reticence may also have been due to the complex geography of his life. From Breslau, then part of German Silesia, he had fled with his parents and sisters to Palestine when he was only sixteen; from there he had gone in 1955 to Glasgow with my mother, Lore, three years after their marriage and, after her death at the age of only forty-four, had moved with my brother and me to London in 1963, where he married Isca, Lore’s younger sister, who now became my second mother. It took me a long time to realise how many losses had ruptured his life.

I find it hard, too, to understand my own ill-timed curiosity. Why had I asked him so little about his relatives, and why was I so full of questions now, when he was no longer there? Or maybe my need to explore the destiny of my father’s family was part of my own mourning, both a tribute to him and an attempt at the impossible task of forming some kind of tally of what was lost. Or maybe there are questions that cannot be framed, not, at least, until long afterwards. ‘Many people come to see me with their enquiries,’ the German holocaust historian Goetz Aly told me. ‘They almost all have one thing in common; they’re over fifty, mostly over sixty, and those from whom they could once have enquired are dead.’

I was there in Jerusalem when Steffi died. The youngest of the four siblings, she’d been just ten when the family fled in 1937. She’d fallen in love at once with the new life in the developing Jewish homeland with its vital spirit, enthusiastic youthfulness and warm outdoors culture. She’d trained as a nurse and worked in Cyprus with the thousands of refugees held there by the British. Hoping to put the horrors of Nazi Europe behind them, they set sail from ports on the Black Sea or the Mediterranean, illegal immigrants on overcrowded boats, desperate to reach the shores of Palestine and begin fresh lives in the incipient Jewish state. Some made it safely to the new homeland; some drowned in sight of ports which offered them no anchorage; some were intercepted by the Royal Navy and interned. ‘Whenever she was home for the weekend they’d come for her passport and use it to smuggle in new immigrants,’ my father recalled; ‘she’d have it back the following day.’ Later she served for years in a small clinic in the Old City of Jerusalem. ‘The first nurse in the Jewish Quarter’, read the simple inscription Michal, my one and only cousin, later chose for her tombstone.

It was a burning June day when we buried her in the ancient Jewish cemetery high on the Mount of Olives overlooking the city she had loved. Few friends joined the small cortège of cabs which followed the hearse; this was East Jerusalem and the steep, narrow lanes bounded by high stone walls could not be considered completely safe. It would have been more convenient to have arranged the funeral elsewhere, but it felt appropriate to lay Steffi to rest in the same cemetery where Eva had been buried back in the Mandate days, before the State of Israel had been declared in 1948 and the city riven in two by the War of Independence. Remarkably, a space had been found where the two women could lie not quite next to each other but at least head to foot, and resume after sixty long and battle-ridden years their sisterly companionship in their final resting places.

After the grave had been filled with dust-dry soil and the memorial rites completed, I went for the first time to visit Eva about whose early death my father had so rarely spoken. I read the words on her gravestone:

Our precious daughter and sister

Chava Elka Wittenberg

daughter of Raphael z’l,

born on the 18th of the month of Menachem Av, 5682 (1922)

and taken in the midst of her days

on the 22nd of the month of Tammuz 5704 (1944)

This was puzzling. The letters ‘z’l’ stood for zichrono liverachah (‘may his memory be for a blessing’). Eva’s father Raphael, my grandfather, must therefore have been dead when these lines were composed. Yet he only passed away in 1954, ten years after Eva, a time in which those extra letters could scarcely have been added since the Mount of Olives was under Jordanian rule from 1948 until 1967 and Jews were allowed no access, even to the cemeteries. The inscription continued:

Granddaughter of the great Rabbi Jacob,

son of Rabbi Avraham Chaim Freimann,

who was born on the 21st of the month of Tishrei 5627 (1866)

and died on the 19th of the month of Tevet 5698 (1937)

and of Rebbetzin Rachel, daughter of Rabbi Yisrael Meir,

who was born on the 1st of the month of Shevat 5629 (1869)

and killed in the Holocaust for the sanctification of God’s name,

in the month of Shevat 5704 (1944),

may God avenge her blood.

May their souls be bound up in the bond of life.

‘For the sanctification of God’s name’ was the traditional phrase with which those killed for their faith were honoured. The objection that the Nazis persecuted the Jews not on account of their beliefs but simply due to their Jewish blood could not be raised here: my great-grandmother had perished not just because of, but deeply immersed in, her faith. As for the words ‘May God avenge her blood’, they had been found scrawled in blood itself on the insides of cells and on the stony surfaces of fortresses where Jews had been shot, kicked or bludgeoned to death.

I walked slowly through the rows of graves to the wall at the edge of the ancient terrace, looking out over the Temple Mount and the city beyond. When did the family first learn of my great-grandmother’s fate? I remembered how my father had shown me a copy of the postcard she sent from Theresienstadt late in 1943, at the Nazis’ behest of course, explaining to her family that all was well and that conditions in the town were perfectly satisfactory. But when did they know for certain that she had been murdered? It could not yet have been in that summer of 1944 when her granddaughter was laid to rest. The brutal facts of the Final Solution were not then understood in their entirety and the family wouldn’t have relinquished prematurely the hope, however improbable, that they might yet hear when the war was over from der lieben Mama, their beloved mother, and that somehow she might have managed to survive.

It struck me then that years later, sometime after 1967 when the Mount of Olives was once more a part of Israel and she could again visit her daughter’s grave, my grandmother must have chosen to commemorate her parents and her husband here, where her precious child already lay, bringing together in death all her loved ones who were prevented by visas, quotas, and decisions the ill-fated nature of which would only be revealed with hindsight, from ever meeting again while they were still alive. Her thoughts would have taken her not only to the memory of her beloved daughter, but of her whole family as once it had been, her father, mother, sisters and an entire world destroyed.

My father’s last remaining sibling, Hella, died nine months after Steffi, just before the carnival festival of Purim. She too was buried on the Mount of Olives, close to her sisters. I went to Jerusalem for the funeral, then hurried home to be with my father during the shivah, the seven days of prescribed mourning. He was suffering from an unspecified illness associated with an autoimmune condition and had been growing progressively weaker for several years. But, as all the family agreed, it was the news of Hella’s death which destroyed his will to live.

Before I left Israel, my cousin Michal and I met at the flat in Jerusalem where the family had lived since the end of the 1930s to go through their remaining possessions. It was the close of an era, especially for my cousin, to whom that apartment, on the first floor of 29 Rechov Ramban, the main route through the centre of the Rechavia district where so many German Jews had settled, had been home from her earliest childhood.

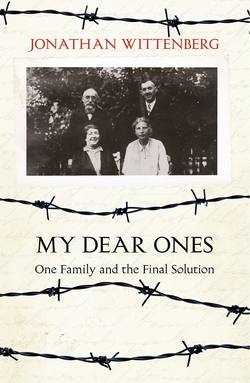

I too had strong associations with that apartment, where I had stayed many times on visits to Israel. There was the bookshelf with the old prayer books from Germany, most of which are now in my own home in London; here in the dining room hung the portrait of Rabbi Yacob Ettlinger, known after his chief work as the Aruch LaNer; outside on the balcony was a pile of old suitcases. As I remember, the case we opened that afternoon was one of those large wood-ribbed travelling trunks that used to be fashionable in the days when railway stations still had porters. Inside was a smaller suitcase in which we found an inauspicious-looking off-white linen bag. In it was a bundle of old papers, letters, bills and documents. In another package were notebooks written in a small, tidy hand. A quick examination showed that they were commentaries to verses from the Bible and jottings for lectures, presumably by my great-grandfather Rabbi Jacob Freimann.

But it was the letters that captured my curiosity. I picked up random envelopes and began to unfold the delicate sheets they contained. A brief glance showed that they were mostly written in German; the paper was thin and time had turned the ink of the addresses on the envelopes from blue to fading turquoise. It was the dates which caught my attention: June 1938; November 1938; March 1939. I began to read. Much of the handwriting eluded my first, hasty efforts to decipher it, but some of the letters were readily legible and a few were typed. I sat for several minutes absorbed and oblivious.

17 June 1938

Dear Mama,

Hopefully the parcel arrived safely. This Saturday is going to be sad for you … What’s happening about your coming to visit us, dear Mama? Have you still not received any information?

The sender was Sophie, my father’s aunt. Scarcely a month later she wrote again:

11 July 1938

Dearest Mama,

The weather has become so nice and cool that I’m going to send off a small box tomorrow. It’ll hopefully be a duck and a chicken, and I’ll pack the gaps with Omega and flour.

What, I wondered, was Omega, and why was her eldest daughter sending poultry to her mother through the post?

There was a list several pages long in pale black ink; the letters were slightly blurred around the edges indicating that this was probably a second or third copy, made by inserting a sheet of carbon paper between the pages. Every conceivable household object was itemised: one clock, twelve knives, twelve shirts, two belts. No doubt the top version had been sent elsewhere, or handed in at some office to satisfy its tedious bureaucratic requirements.

So far all the letters were from 1938. But then I drew an equally thin but larger sheet of writing paper out of its envelope; it was dated 10 January 1947:

Dear Frau Ella,

I received your letter of the 14 September at the end of November. I beg you not to be angry that I’m only answering it today … Your dear mother wrote the following words: in spite of everything my faith in God remains unshakeable. These words accompanied me through the long years of persecution and bombing, when more than once our life hung by a silken thread, and gave me the strength to bear it all and come through.

Ella was my grandmother; this letter had been posted in Berlin to her Jerusalem address. But who was the sender, Charlotte Tuch? This was not a name I had ever heard mentioned before. And what relationship did she bear to my great-grandmother that she should be aware of her innermost thoughts before she died?

‘If it’s all right with you, I’d like to keep these,’ I half asked, half told my cousin as I returned the bundle to its off-white bag. I did not realise then the depth of the journey on which they would lead me.

I took the bag back with me to London, where we were all absorbed in caring for my father during his final days. I remember asking him about his aunt Sophie shortly before he entered that domain in which it was no longer possible to elicit the kind of information which is dependent on a practical and sequential awareness of the affairs of this world. ‘She came to visit us in Palestine in 1937,’ he said. ‘We told her not to go back to Europe but she wouldn’t listen. Her husband was a Czech nationalist; he believed they would be able to fight the Germans off. They were very wealthy in Czechoslovakia. “It isn’t safe there; stay here with us,” we told her. She wouldn’t hear of it.’

That was the last time I was able to ask my father about such matters, or about anything else.

It was the following year, on the night of the fast of Tishah Be’Av, next to the light of the memorial candle and in the presence of the list of names of the martyred members of the family, which my father had enjoined me to place there, that I began to organise and file the papers I had found in that trunk. Now at last I could begin to study them.