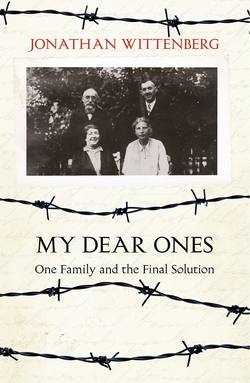

Читать книгу My Dear Ones: One Family and the Final Solution - Jonathan Wittenberg, Jonathan Wittenberg - Страница 11

4: ‘DISCHARGED FROM YOUR DUTIES’

ОглавлениеOn 16 July 1938 a friend working for the Palestine Office in Berlin replied to Alfred’s urgent enquiries on behalf of his mother, about whose situation he was deeply worried:

Dear Alfred,

Many thanks for your lines. They led me to make a long-intended visit to your mother to discuss her situation with her. Sadly, the matter is in several respects more difficult than it looked back in May because circumstances have become significantly worse in a number of ways.

The letter explained in great detail the various options which might still remain open; its author was closely conversant with the advantages and disadvantages of each of the categories under which it was possible to apply to the British Mandate authorities for a visa to Palestine.

Of all the six children it was Alfred who was most aware of the urgency of getting his mother out of Germany and who was most able to act. By now two of his sisters had joined him in Palestine, but he was the longest settled in the country and his legal background equipped him best to understand the numerous difficulties which had to be overcome.

The youngest of the Freimann children, born in 1899, Alfred had thrived in the atmosphere of intense Jewish study in his parents’ house. ‘As he was always at home he learnt much more from my father than I,’ his older brother Ernst recalled. ‘He was always reading or learning.’ Whereas Ernst had been obliged to serve during the First World War, Alfred didn’t turn eighteen until close to the end of hostilities and the Jewish farmer to whom he was sent for war work allowed him to stay at home with his books. This enabled him to write, at the age of just eighteen, a highly commended biography of the famous thirteenth-fourteenth century legal authority, Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel. Throughout his life his great love was Jewish scholarship. In the autumn of 1922 he wrote to the committee of the nascent Hebrew University, then based in London; he had heard that the department of philosophy was looking for teaching staff. ‘I trust you won’t think me, most respected sirs, over-bold in turning to you in this regard,’ he began. He described his studies with his father, ‘where I drank my fill of the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds and numerous legal works. My longing for Torah grew ever stronger; I laboured in it and found reward.’ He wrote of his fascination with the history of Hebrew literature; he mentioned his book and noted that it had been favourably received by the leading scholars of the generation. But his real passion was Hebrew jurisprudence; it was to this subject that he wished to dedicate his life. Alfred was not quite twenty-three when he wrote the letter. Almost two decades would pass, bringing with them events unimaginable at the beginning of the Weimar Republic, before he was eventually invited to join the Faculty of Humanities of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

In the meantime he opted for the law as a way of earning a living. He was made Gerichtsassessor in 1926, a two-year probationary placement, and was scarcely thirty when he was appointed to the Prussian judiciary. The constitution of the Weimar Republic made discrimination in access to the professions illegal, affirming that ‘admission to public office was to be independent of religious affiliation’. His certificate of appointment, dated 25 June 1928 and written in magnificent Gothic script, declared that ‘Probationary judge Dr Alfred Freimann in Tilsit is herewith appointed to the position of regional, and at the same time that of district, judge.’

He was sent by the Prussian Ministry of Justice to Königsberg in East Prussia, where he met and fell in love with a friend of the daughter of the lady who managed the establishment in which he took lodgings. Nelly Basch, originally from Luxembourg, had lost her parents at an early age and was brought up in an orphanage. The couple were married in the summer of 1928 in Posen. The civil certificate was stamped with the seal of Alfred’s father; officiating at the wedding of his son must have been one of Jacob Freimann’s last, and happiest, duties before leaving for Berlin.

I remember Nelly well; she was a kind, homely, down-to-earth and practical woman, devoted to her family, and served wonderful cakes. She possessed great strength of character, no doubt forged in her challenging childhood and toughened by the subsequent tragedies which continued to punctuate her life.

In 1933, when the Nazi party came to power, there were more than three thousand Jewish lawyers in Prussia, over a quarter of the total number of practitioners in the region. This ‘over-representation’ was resented; on 31 March the Prussian Minister of Justice, Hanns Kerrl, announced measures dismissing most Jews working in the civil service and the law, ordering that ‘only certain Jewish attorneys shall practise, generally corresponding to the proportion of Jews in the rest of the population.’ This figure would have stood at less than one per cent. It seems that Kerrl took these steps on his own initiative, prior even to the promulgation one week later by the Nazi government of the Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service that mandated the dismissal of all non-Aryans. The latter category was defined as excluding ‘anyone descended from non-Aryan, particularly Jewish, parents or grandparents’. To lose one’s job, just one ‘wrong’ grandparent sufficed.

Alfred had been practising his profession for scarcely three years when he was removed from his post. A subsequent letter from the Prussian Ministry of Justice, dated 3 July 1933, by which time he was already in Berlin, informed him of the supposedly ‘initial’ duration of his ‘retirement’:

By means of this letter, you are discharged from your duties as of 7 April 1933 until 1 November 1933, on the basis of section 3 of the Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service. Your retirement will continue until this date.

Referring to a series of bye-laws, the letter made it clear that ‘no severance payments are due’. The signature was illegible. The envelope was marked persönlich, followed by an exclamation mark. One might wonder why; Alfred’s colleagues would surely have known exactly what the receipt of such a missive meant. Perhaps the sender didn’t want other eyes to see the cold details of how the ministry dismissed its faithful servants. It would be hard to imagine a letter which showed less personal concern.

Letter to Alfred Freimann discharging him from his post in the Prussian judiciary.

The act in question, the Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service, was to affect many thousands of people, often costing them the positions to which they had given decades of diligent service. In Frankfurt, Alfred’s uncle Aron, a notable scholar who had devoted his life to developing the Judaica collection in the municipal library into one of the finest and most extensive in the world, was summarily ‘retired’ and shortly afterwards required to hand in his keys to the building.

Soon after receiving notification of his dismissal, Alfred was tipped off by a non-Jewish colleague who had seen his name on a Gestapo list. He advised him to leave Königsberg at once. Alfred departed for his parents’ home in Berlin with little more than the coat on his back. Nelly followed two days later with their three-year-old daughter Ruthie. They, too, took no luggage; nobody could be trusted, not even the nanny. Safer in the comparative anonymity of the capital, and close to the offices of the Treuhand-Stelle, they applied, successfully, for certificates for Palestine. Parting from his parents must have been hard; Alfred was perhaps the closest to his father of the six children in temperament and interests and even in 1933 it must have been far from certain that they would ever see one another again.

A year after arriving in Palestine Alfred left the country, albeit temporarily, drawn by the opportunity of teaching at the University of Rome. But it was not to prove an attractive option. ‘We went to Italy,’ Nelly told me. ‘Mussolini was already in power. I said to Alfred: “We’re not staying here. We’ve seen it all before. There’s only one place we’re going to live.”’ They returned to Palestine where, with no opportunities available in the academic sphere, Alfred took a position as legal advisor to an insurance company. At night he followed his passion for scholarship. Paper was in short supply; he used the backs of insurance forms, covering them with notes for the book he was preparing on Jewish marriage law, to this day considered a classic study on the subject. Further jottings showed that he was already at work on the sequel, a history of the Jewish law of divorce. All through his life he had a passion for Jewish books, which he collected avidly despite the limited means at his disposal.

In 1935, Nelly gave birth to their son Dani, the first member of the family to be born outside Europe. Alfred’s parents travelled from Berlin to join them for the celebration of the circumcision. It was a journey Regina would longingly recall:

This week brings Passover … In the year of ’35 we arrived in Palestine during these very days; the joy of our dear departed Papa when he saw the land from the ship was indescribable. What has happened since that time!

Had it not been for his sense of duty towards his beleaguered congregants back in Berlin, Rabbi Freimann would have remained in Palestine, Alfred’s daughter Ruthie told me as we sat in her home in Tel Aviv seventy-five years later. She must have been just five when they came to visit; it was the last time she would ever see either of her grandparents.