Читать книгу Skogluft (Forest Air) - Jorn Viumdal - Страница 8

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

THE STRUGGLE IS REAL—AND CAN BE OVERCOME

FATIGUE IS ONE OF THE MOST COMMON CONDITIONS IN MODERN SOCIETY

A gentle breeze blows across the sheltered bay. The sun warms your toes as you wiggle them in the soft sand. You’re sitting on your favorite beach looking out to sea, and the distant cries of the seagulls ring in your ears—

“Ahem! Ah-hem!” That was no seagull—it was your boss. She apologizes for disturbing you and asks: “Is that chair comfortable to sit in?” She thinks you look a little uncomfortable. Maybe you should be looking for a job somewhere else? Somewhere with more comfortable chairs, perhaps? You hurriedly assure her that the chair is excellent for sleeping—I mean, sitting in—and that, of course, you are content with everything. No, no, you weren’t sleeping. Yes, yes, you’re completely sure. The meeting continues. You sit up very straight in your (not very comfortable) chair and try to focus your wandering attention on the next agenda item. You were lucky. This time.

Some of what makes a vacation feel so different from everyday life can be brought back with you into your home and your place of work.

Important Info

If you’re the type who daydreams about the mountains or the sea or the forest instead of making that phone call, washing that load of laundry, or closing that deal, you’re not alone. Many people—including your boss—reminisce fondly about their vacations (and perhaps even a touch bitterly, because they seemed much too short).

At the risk of disappointing you, this book is not about showing how to turn every day into a vacation. Experiencing the peace and contentment of a vacation in the midst of a busy work life filled with obligations is difficult—if not impossible. But some of what makes a vacation feel so different from everyday life can be brought back with you into your home and your place of work. And doing this doesn’t require complicated feats of technical engineering or a steady drain on your bank account.

How often do you feel tired in the middle of your day, as if you can’t possibly take one more meeting or phone call? By late afternoon, have you used up every ounce of the energy you felt in the morning? Have you come to expect this lethargy as inevitable, with the only antidote being a cup of strong coffee or a large candy bar, the sweeter the better?

If your answer is “Why, yes, every day at around 2:30 I want to curl up under my desk or under the laundry hamper and take a long nap,” join the crowd—this is, unfortunately, an age-old problem in the history of the human race. More than two thousand years ago, the ancient Romans complained of fatigue as their towns and cities grew larger and their everyday lives became further removed from nature. Having recently shifted from an agrarian to an urban way of life, they felt the urge to travel out into green areas in search of rest and relaxation.

As in so many other realms, the ancient Romans were forerunners in stress reduction: They recognized that something crucial was missing from their lives and sought out solutions to the problem. Today, there is a plethora of solutions offered by scientific advances and a heightened awareness of the impact of environmental factors. But when you begin to sleepily count the hours to the end of your workday and yearn for a nice hammock in which to sleep the afternoon away, chances are you’re not thinking about what lies behind this onset of fatigue. But unlike the Romans, modern people have no idea what lies behind their ailments, and as often as not lay the blame on themselves.

I have a term for that nagging sense that something is missing: “lacking nature.” It is a term that gathers together the all-too-familiar symptoms that invariably appear under certain conditions.

What sort of symptoms? Through the thirty years in which I have been researching and developing healthy workplaces, the following symptoms are so common that they can be mistaken for everyday annoyances:

Headache

A groggy, heavy feeling

Fatigue

Respiratory tract irritations

UNDER WHAT CONDITIONS DO THESE COMPLAINTS ARISE?

During the winter

Usually indoors and in urban environments

When we cannot see, smell, or touch green, healthy plants

When the light around us is too weak or too bright

Have you noticed that the symptoms read more like a schoolchild’s excuses for staying at home on a particularly miserable autumn day? Compared to a broken bone or the bubonic plague, they really don’t seem to be a big deal. You’re right to be critical when someone comes along with dubious claims concerning some (usually expensive) means of curing quote common, “trivial” problems. But these small problems are what a great many people face on a daily basis. They aren’t excuses but symptoms we experience when we don’t feel ill enough to skip school or work (even though we would very much like to). And in many sectors, such as security and health, these problems are not at all minor matters. They can be the difference between a right decision and a wrong one—a choice that can be the difference between life and death.

Look again at the four types of conditions (see here). Note how two elements in particular recur—a lack of light and a lack of plants. And note another important distinction—there are conditions over which we have no control.

We can’t change the seasons of the year, for example, although some people are able to travel to seek out light and nature. And unless we happen to be high up in the command chain, we can’t do much about access to light and to nature in places where we work or in public spaces. But note there are conditions we can change. Hence the two reasons why I wrote this book.

The Number 1 Reason: WE NEED TO UNDERSTAND EXPERIENCING A LACK OF NATURE IN ONE’S LIFE IS A PROBLEM.

The Number 2 Reason: THIS PROBLEM HAS A SIMPLE SOLUTION.

So the next time you feel a headache, fatigue, or a nagging cough, don’t dismiss it. It’s easy to disregard these vague symptoms—when we can’t pinpoint a reason for why we feel bad, we presume that we’re imagining our symptoms or that we’re weak. And that is why we assume that the ailments will disappear if we just pull ourselves together. That is why we feel the solution is a matter of willpower.

WHERE THERE IS A WILL, IS THERE A WAY?

Willpower is like a modern-day superpower—we say it can conquer everything from obesity to addiction, clutter to bad grades. If you have used willpower to overcome a bad habit or to teach yourself something new—congratulations!

Willpower enables us to triumph over petty egoism and reach higher goals, for the benefit both of oneself and others. It gets us involved in issues that truly matter. And yes, willpower can also be put to such pursuits as competing with friends to see who can hold their breath underwater the longest, staying awake to binge-watch a favorite TV series, or scaling Mount Everest without oxygen. As fun or impressive as these feats might be, we could say that they take a lot of energy (or even waste it). The reverse side of willpower, so to speak.

We also use willpower to force ourselves to do things that might be detrimental to our health. Does it make sense to “pull ourselves together” in order to survive in circumstances that are harmful, just to demonstrate that we can? Would you, for example, sleep on a bed of nails every night simply to prove that—well, I really don’t know what that would prove, other than that you have a lot of nails.

Let’s look at another example. Suppose you’ve enjoyed a good night’s sleep. But by midmorning you’re nodding off. Yawning, rubbing your eyes, taking brisk walks to the coffeemaker, you stubbornly resist lying down and sleeping the rest of the morning away. At the end of a long, long day, you feel proud (because we all know that a person who can overcome tiredness has both good willpower and a strong character).

But there might be a very simple reason why you feel tired or unwell. Your body is trying to tell you something, sending subtle messages like “The light in here is very poor. Is it evening already? Might as well take a nap,” or “This place isn’t good for us. Let’s get out of here.” When the message doesn’t get through, then it resorts to stronger methods, bringing on headaches, a feeling of lethargy, or bouts of coughing. You begin to feel a little stressed or unwell. And if you ignore these messages, you have again demonstrated a willpower you can be proud of. But at what cost?

Think about using your prodigious willpower to some other end. After all, when you have to use great strength of will simply to accomplish a small task like staying awake, isn’t that a little like having to pay a fee every time you use your debit card at another bank’s ATM (I will do anything to avoid having to pay that fee, including going miles out of my way to find a bank that does not charge one.) And suppose the fee was as big as the amount you wanted to withdraw? Wouldn’t that just be a waste of money? Of course it would! And yet when it comes to our health and well-being, we allow this kind of energy drain to happen every single day of the year. The subtle yet powerful effects of this lack of nature forces us to make unnecessary and exhausting compensations to attain our goals.

The simple method that takes care of this problem was clearly recognized by the ancient Romans: Life is better when you’re close to plants. Many of you are nodding your heads and thinking, “Oh, I wish I could spend more time out in nature. I wish I could be surrounded by nature the whole day long.”

This is where the “recharging the batteries” argument comes in—the idea that we take an hour, a day, or a few weeks off in a beautiful spot in order to relax and replenish our stock of energy, which we then spread out through our everyday lives at work and at home. People refer to this all the time. Especially when talking about other people. (“Nina shouldn’t look so tired. She just got back from a vacation.”)

When people say “recharge,” they think of it like filling up with a green fuel, like having a large reserve of nature that they can run on a little at a time through the days, weeks, and months that separate us from our next immersion in green. It sounds fantastic, and it really is—it belongs in the realm of fantasy.

Don’t get me wrong, it isn’t imaginary that we benefit from a walk in the woods. And who regrets having been out in nature? The problem is that the effect does not last. You’ve had a lovely restorative break and you’ve dived right back into your day with great enthusiasm … only to find yourself drained of energy after a couple of hours.

Perhaps, as you again sink into lethargy, you are already telling yourself the usual solution. Like the annoying chorus of a tune you can’t get out of your head you hear that repetitive little refrain: “Show some willpower!”

Willpower works, no doubt about it. It helps us ignore our headaches, tired eyes, coughing, and more. But by using it we suppress the signals the body is trying to send us so that we can follow the short-term dictates of duty and responsibility. We can’t possibly lie down and sleep at our place of work, even if the light is so bad the body thinks it is night. We can’t possibly stop a task every time we get a headache. We can’t possibly go outside and breathe fresh air every time the air indoors becomes too dry or stuffy. We soldier on and carry out the everyday tasks demanded of us. Because we feel we must.

Please, I am not suggesting that we don’t use willpower. Don’t ever just sit down and give up (or fall asleep under your desk—that would not do). But imagine that the first thing you felt when you entered a room at work or at home was not “Oh no, not another day in this place,” but instead “I really look forward to getting started!”

Did you notice that? I wrote about what you felt when you entered a room. Whether your energy arrow points up or down is not a matter of personal choice. Even before you start consciously thinking, “Hmmm, the lighting is rather dim here,” or “The air is so stuffy,” or even that it’s too crowded or sparse, your body has already been paying attention and has made up its mind.

SPACE DRAIN

Your body is wise. Evolution has honed your senses into a razor-sharp analytical tool that needs just a fraction of a second to deliver an assessment of a situation. The forceful assessment “Get out of here” is still useful after millions of years of dodging predators and environmental hazards, but this course of action might not be a realistic alternative if the assessment comes in the middle of, say, delivering a PowerPoint presentation, negotiating a contract, or working through the umpteenth pile of laundry as a caregiver. But the fact that there are no obvious dangers present doesn’t mean that your body isn’t sensing something detrimental to your health. When the “fight or flight” response kicks in, being responsible bosses and coworkers and caregivers, we suck it up and pull on our energy reserves. Whether we want to or not, whether we feel “right” about being in whatever kind of environment is triggering the body’s response, we have to summon our last resources. Day in and day out.

Suppose we didn’t have to pay this price. Suppose we were spared from making this kind of effort (just to accomplish mundane tasks at home or at work, much less to do what we dearly would like to do). Imagine feeling that your workplace or your home rejuvenates you. Imagine that your senses are reassuring you that you are in a safe, healthy place. You would have plenty of energy for living the life you want to lead. For your interests. Your job. Your children. Your friends.

FACT: THE ENERGIZER BUNNY IS NOT A REAL PERSON

There must be a better analogy for our energy levels than rechargeable batteries. When I hear people talk about “recharging” themselves, I’m reminded of the old joke about the miser who kept running in and out of his house carrying an empty sack. Why? To save money he had built his house without windows, and now he had to gather enough sunlight for the evening! As any schoolchild knows, you can’t store sunlight in a sack. Likewise, you also can’t run out and gather up some energy from nature, store it, and portion it out to suit your needs—especially not if you find yourself in surroundings that drain you of energy.

We just have to admit that the term “recharging” isn’t accurate. Worse, it’s misleading. People don’t have anything like batteries for storing energy, so when we use that expression we’re actually making unreasonable demands of ourselves. The energizing, healthful effect we get from walking out in nature doesn’t last very long, and it cannot be stored in the form of a sort of dividend that can be paid out later. But are there positive effects to be gained from taking regular walks in nature—and, specifically, the forest?

I’ve been in the business of improving workplaces and homes for thirty years; time and again, I’ve seen that we need to “top up” our supply of nature every day, 24/7, in order to give our best, and, most of all, to feel healthy. And there is scientific research to prove this, as you will see. Scientists and researchers have documented a score of specific and measurable physical and mental health benefits from being out in nature. Walking along forest paths, breathing in forest air, and seeing the dappled play of light among the leaves definitely does a body good. However, the problem—which led me to develop the Forest Air method—is that this restorative energy cannot be stored and used later.

Because our bodies don’t act like a battery, we tend to be like the miser, scurrying in and out of our homes and workplaces hoping to capture some life-giving rays.

Important Info

A DEEP DIVE INTO FOREST BATHING

For years, Japan’s national health service has been encouraging people to indulge in shinrin-yoku, “forest bathing.” I love how the word evokes humans diving into the bushes and splashing about among the leaves, but shinrin-yoku simply means going for a walk in the woods (just as many Norwegians do!). The purpose of shinrin-yoku is not to lose weight or to get a stamp in your passport or to rack up steps on your Fitbit. (Although all of these, of course, can be part of a bath in the forest.) Instead, the walk should be short and leisurely; exercise is not the main aim. The ancient Romans instinctively turned to nature to feel better. The Norwegians have made a national pastime out of walking in nature. Immersing oneself in the atmosphere of the forest has become an integral part of preventive care and healing in Japanese medicine. What is it the Japanese know that the rest of the world doesn’t?

The unmistakable fragrance of a stand of evergreen trees is representative of the fact that all plants exude fleeting organic compounds called phytoncides, which are used not only as a defense against enemies, but also as a way to communicate with other plants of the same species. These compounds, such as the pinenes and limonenes of evergreens, form an aromatic cocktail that is regarded by the Japanese as highly beneficial for health. Immersing oneself in a forest doesn’t just feel calming and restorative; since 2004, researchers in Japan have investigated the effect plants have on health and well-being. Lower blood pressure and anxiety, less irritation and anger, and a strengthening of the immune system were found to be, literally, a walk in the park.1

Even in the sterile environment of a research lab, far from a forest, health benefits were noted. Experiments showed that just a photograph of a restful nature scene conveying shinrin-yoku was enough to cause a drop in blood pressure. Just the scent of certain ethereal oils from forest plants caused a greater drop in blood pressure than other smells. And just touching a natural material like an oak plank had the same effect—an effect that was not demonstrated when this same material was coated with a layer of paint.

Experiments were also conducted in the open air. In Chiba, Japan, a control group took a bracing stroll around the city’s railway station, while another group walked for twenty minutes in an oak forest in one of the city’s parks. The physiological and mental responses of both groups were then tested. The forest group not only showed clear signs of heightened cerebral activity but exhibited improved concentration. The forest group also had a lower count of cortisol compared to the control group. Cortisol is known as the “stress hormone” for good reason, as a high level of cortisol is one of the signatures of elevated stress. A short walk among the trees was all that was required to lower the concentration of this hormone—to de-stress.

Another of these experiments, carried out in 2010, tested the nervous systems of participants who were split into two groups, one walking in the forest and one walking through a built-up urban environment. The forest group had lower levels of cortisol, lower pulse rates, reduced blood pressure, an increase in the activity of the parasympathetic nervous system, and a reduction in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. These last two results were particularly exciting for me to see.

Remember learning about the nervous system in biology class? The sympathetic nervous system is the part of the autonomic nervous system that enables us to react swiftly to dangerous situations (the “fight or flight” response), while the parasympathetic nervous system is what calms us down when the danger has passed. So elevated levels of activity in the sympathetic nervous system means that you are prepared and ready for conflict. Our ancestors had to deal with fierce predators, while today our bodies seem to get keyed up to fight (or flee) at the drop of a hat. (Just think of the tension and anxiety you feel in a traffic-snarled commute.) Researchers were able to document a very important connection:

Shinrin-yoku soothes your unease and helps calm you down after agitation.

Later studies have also shown that green surroundings have a favorable impact on chronic stress.

Important Info

And for those who suffer from debilitating anxiety or illnesses, later studies have also shown that green surroundings have a favorable impact on chronic stress. An experiment carried out in the 1990s at Hokkaido University showed that shinrin-yoku led to a significant lowering of the levels of blood sugar in people suffering from type 2 diabetes, on average a change from 179 mg/dL (before a walk in the woods) to 108 mg/dL (after). Does the length of a walk matter? In this experiment, apparently not: Subjects walked between two miles and four miles, but the length of the walk had no impact on the results.2 Good news for those of us who just don’t have the time to walk for hours every day, as much as we would like to!

BUT YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU

Around the world, researchers back up the claim that a simple walk in the woods works wonders. As much of the world’s population now lives and works in cities, the question for researchers then became how different urban environments might effect one’s sense of well-being. Finnish researchers in Helsinki, in a study published in 2014, investigated just that. In three groups, participants traversed busy city streets, a green space in the middle of the city, or a wooded area. Would they feel restored? Filled with vitality? More creative? Hands down the wooded area made people feel the most restored, vital, and creative, but the city park also had a marked positive effect on the participants’ well-being. Another striking observation? Stress levels not only went down, they went down quickly.3

People feel better after taking a walk in a park, but can these feelings be measured? In the United States, researchers at Stanford University studied the psychological effects of experiences of nature on both thoughts and feelings. Subjects were divided into two groups, each of which was to take a fifty-minute walk in the Stanford area in either a high-traffic urban setting or in a park. A series of psychological tests was conducted before and after the walk. Those who had walked in nature reported lower levels of anxiety, fewer depressive thoughts, and fewer negative feelings. Higher scores in memory tests showed that their intellectual capacity had also increased. Another study made by the same group of researchers investigated the effects of walking in the woods on common urban ailments such as depression and negative thinking. This study too showed measurable physical effects on the activity of the brain: lower levels of activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex (sgPFC), the part associated with self-centeredness and chronic worrying.4 Walking in nature isn’t just a feel-good exercise.

A walk through the woods also helps those suffering from chronic physical pain. In a South Korean study, patients suffering from serious chronic pain participated in a forest-therapy program. These patients showed marked physiological improvement in two areas: heart rate variability (HRV)—the measure of time between each heartbeat and an important factor in maintaining the autonomic nerve system—and natural killer (NK) cell activity, which strengthens the immune system. Participants said they experienced lower levels of pain and felt less depressed, and they described feeling that their quality of life was better.5 Interestingly, these results are not about the effects of physical exercise or meditation in nature—just hanging out in nature, leisurely walking through the forest.

Don’t just take my word for it. Scientists have weighed in. Whether you call it shinrin-yoku or a walk in the woods, immersing yourself in nature will:

Strengthen the immune system

Ease pain

Lower stress

Have a calming effect

Control blood-sugar levels

Reduce depression

Improve mood

All from a walk in the woods!

You might have already discerned a small but important problem: You can’t take all of these positive benefits with you. On your lunch break, you’ve just walked out to a park and filled your lungs with the fresh scent of pine trees. You’ve returned feeling restored, soothed, and ready to tackle the afternoon’s tasks. But as you leave the green, light-filled setting and enter an unhealthy indoors environment, you begin to feel that familiar, dispiriting energy drain. It’s back to grabbing a chocolate bar or a cup of coffee and our old friend willpower again.

How can we break this cycle? Ever hear the well-meaning but impractical advice “Either you move to the country or you move the country to you”?

The first suggestion works for people attracted to the idea of sitting on a tree trunk in the middle of the woods whittling willow flutes, making calls on bark-hewn telephones, and now and then stirring to shoot a deer for dinner. But if you don’t have a job that puts you directly in touch with nature, then this solution is not feasible—most people need to live and work in urban areas. As for the second suggestion, the idea of bringing the country closer to the city and even indoors reminds me of tragic stories I hear about wild animals accidentally entering the world of humans. A raccoon can carry disease. A bear is cute until she is protecting her cubs. A wild animal can cause loss of life and property, not to mention the animal potentially losing its own life. Moving out to the country—or moving the country indoors—just isn’t feasible. So thanks for that advice, but no thanks.

WHAT YOU NEED, WHERE YOU NEED IT

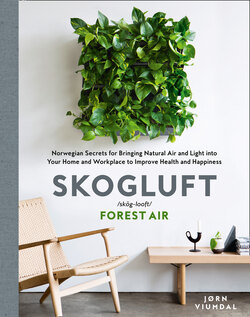

As I said before, our bodies are wise. What we most want around us is precisely what we need most from nature: light and plants. I’ve joined these into a single concept and developed a method: Forest Air.

Experts have demonstrated clearly that incorporating plants and specially adapted light indoors has a huge positive effect on people’s physical and mental health, almost as powerful as the effect of actually being out in nature. The effect has been noted in the workplace, in schools and institutions, and across people in all age groups, occupations, and life situations, from doctors, laboratory technicians, and teachers to students, children in preschool, and hospital patients. In essence, it can be argued that it is a universal medicine.

Not to be a contrarian, but I have to argue that no, it isn’t. Do you claim to have given medicine to a fish you’ve released back into a river, or to a captive mouse you’ve set free in a forest undergrowth, or to a disoriented bird you’ve helped get out of a house? What you deserve real praise for is that you returned them to the environment to which they are best adapted to live—the only surroundings in which they can grow and thrive. And I think you deserve no less for yourself.

YOUR NATURAL ENVIRONMENT AT HOME, YOUR NATURAL ENVIRONMENT AT WORK

I’m not suggesting that you carry whole trees into your house (although by all means do so, if you have the space). Nor am I talking about putting some sad little potted plant in a corner. What you get with Forest Air is a small area of living plants that grow in a controlled and predictable way and that you can take care of yourself with minimal effort. And you’ll get the same health benefits as you would from a walk in the woods. You experience a shinrin-yoku just where you are, every day, without having to go out into the woods.

Say you get a headache while you’re hard at work at your desk. You could just take an aspirin, but if you notice that your computer screen is too far from your eyes or your chair is too low, contributing to the headache, you would try to adjust them. We often try to organize elements of our environments so that they are in harmony with our bodies’ wants and needs. It is a course of action that will potentially stop you from feeling ill in the first place—quite different from taking an aspirin. In the same way, give yourself the chance to see, smell, feel, and touch plants in your everyday environment and provide yourself with good lighting. You will agree: It is not a luxury but rather a daily ingredient that gives you an improved quality of life. Which is something you deserve.