Читать книгу Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire - José Manuel prieto - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеLIVADIA

The girl in the Post Office handed me a second letter from V. She watched with a smile as I turned it over in my hands, incredulous. Out in the street, a cloud of children swirled around me, Greeks, Armenians, Tartars with biblical curls. A youthful chorus asked the time, but I opened the envelope, oblivious to their cries, as if I had jumped up to close a door, shutting out music that was too loud. V.’s greeting resounded in my ear, like in those movies where the offscreen voice descends on a character, getting too close for comfort. Or like that old tapestry (in the north wing of the Hermitage?), an angel unrolling a parchment for a boy in a saffron toga and sandals, his bowed lips at the ear of the rapt youth. When my eyes had made their way to her name on the last page, after reading a letter perhaps more beautiful than the first, I stood stunned for a moment, scarcely aware of my surroundings, immersed in absolute silence, her words of farewell ringing in my ear like a glass bead bouncing around the walls of a seashell, speeding through the spiral chambers. My eyes lifted from the page, darting around, where was I? where had my walk taken me? not really a walk, a glide past walls, entrances, standing at the crossroads, watching two cars go by, then a wagon, pulled slowly by a Percheron (its flanks and feet covered with long hair), as if I was running on automatic pilot, like ships use on the high seas, functioning only enough to move forward, to get around without bumping into things. I blinked and my eyes were caught by something vertical, which got bigger and bigger; then I was hit by a wave of images, breaking over me in a dizzying flood, indistinguishably. They were clear signals of where I was, but only images, no sounds, and they slid past my retina so fast my head spun, each vision of the place rushing past before a single thing, any detail, could pull up on my memory bank. I knew that I must order my ears to reconnect to the exterior if I were to have any hope of grasping some part of the tide of images coming at me, so I went back to open that door and was struck by bursts of sentences, the music (a Greek melopoeia) of the place, and heard clearly: “Two octopus in ink for table five,” and there in front of me stood the person who had turned to shout (I had seen it a second before: the mouth appearing over the shoulder, opening, yelling, the vein in the neck distending—all of which was captured by my ears after a slight delay and subsequently deciphered by my speech centers as an order that this man, the waiter, was shouting to the kitchen).

The crystal bead crashed against the nacreous shell one last time. As if awakening from a dream, I saw the mocking face of Diodore (Diodo), the Greek, and knew I was in the restaurant with the bay window, and I ordered: “A beer. Dark. Draft.”

I had stopped at this restaurant many times. I had spent hours reading letters, copying sentences, whole paragraphs, with the secret hope that if I repeated those words written one, two hundred years ago (and more), my hand would acquire the skill of the ancients. I hoped, for example, to acquire a sense of freedom by copying a passage from Petrarch, describing the ascent of Mount Ventoux, from a letter dated April 26, 1351, into the reply I was starting to draft, sitting in the bay window of the restaurant, looking down on Livadia. The Faustian impulse, the craving for travel of this “first modern man”: “Inspired only by a desire to contemplate the lofty elevation of the place, I have today climbed the highest mount in the region, known, not without cause, as Windy … I stood astonished and overwhelmed by the vast panorama and by the unusual breeze that was blowing …”

I too was “astonished and overwhelmed by the vast panorama” from the Greek restaurant high above Livadia, the spot on the globe I had chosen to see. V.’s letters completely altered this setting. Instead of a simple nature preserve (for yazikus butterflies) I now saw beeches, oaks, cypresses—a row of tall cypresses marking the end of the gentle slope on my left—and the harbor in Yalta, boats anchored there, boulevards running down toward the sea. The octopus I impaled on a broad fork with large tines and raised to my lips came from this very sea. I chewed it slowly, its thick sauce spreading an oily cloak over my taste buds.

With my back to the little restaurant where Diodo was moving between the tables, I leaned over the balustrade and studied the afternoon light, just a hint of the shadow of the hour floating in it: the rays of sun slanting through the clouds and growing shorter, the pyramids of poplars growing less sharp, withdrawing slowly into a larger darkness in which it was impossible to distinguish the branches, their foliage dissolving into a green-blue mass. It wasn’t that everything had become obscured (it was far from totally obscured), no, the initial change here was just as fast as a nightfall farther south, but then a brighter twilight lingered as long as another five hours, with the sun hanging a few meters above the sea.

I rested in my room for a few hours. It was already dark, but for me a good night began at midnight, when no light at all filtered through the curtains. I surveyed the garden in front of the pension, leaning over the rail around the veranda, toward the beech trees in the distance, my eyes wide open, pupils dilated in the low frequency light, infrared. In the painfully harsh light of day, I could not help noting the differences between Crimea and the outskirts of Stockholm, for one example. During the day I registered every detail with my eyes half-closed, hidden like some bird’s behind a double eyelid (or the lace-curtain shutter of a camera), the disk of the sun suspended in a deep blue sky, the bright colors of the bikinis on the beach. I had lived in the north for years, traveling in geographic zones, regions that received less light for most of the year, but more rain and snow, often visiting cities where it snowed as late as May, Stockholm, for example; if I was going there in May, I would certainly take my warmest overcoat, wear it when I left St. Petersburg, to board the train in the Finland Station, and then keep it near me in the luggage rack, so I could put it back on in Helsinki, to board the ferry to Stockholm. I would open it when I got inside, in the glassed-in cabin, pulling the zipper down without taking my eyes off the black rocks along the coast, the dark cold water, the gray sky, good indications of a northern country, no palm trees, no yellow orb throwing thousands of watts on them. A breath of cold air, at last. Yes, I should turn up the collar on my overcoat.

A trip should be traced beforehand in a traveler’s soul, in a tiny polygon like a Wilson camera, where you can follow the trajectory of an atomic particle, to arrive at the state of satisfaction that awaits on the other shore, the water boiling in the kettle, the sun hidden behind the trees, the bashkir guides chatting quietly a few steps away, in their makeshift stores. Because of the importance of the physical, of skin exposed to the wind and sun through the eyelids. But the mental and spiritual are just as important, the heightened experience that allows us to watch entranced as bubbles rise through liquid, to see the universes contained within their narrow walls. An idea that is elusive and fragile, the wings of a butterfly, a dream. Two dreams winged my feet, speeding my descent from the platform. The first, a Chinese parable, I will not repeat, as it is commonplace; the second, maybe less so. (I felt so alive throwing my knapsack onto the luggage rack, drinking homemade liquor with the chance companions on my trip, some Cossacks from Zaporoshets, wrapped in red kerchiefs, just a masquerade for the weekend; it’s true, but so what?)

A man travels to the past like a light ray, cutting through time as easily as a hot knife though butter, as cleanly as night-vision goggles penetrate the darkness. That ray lights the part of the Jurassic forest he is moving through. The traveler can’t leave the path, can’t join the flutter of birds and butterflies on either side, it is forbidden. But he happens to stumble and accidentally steps on a butterfly. That’s all he does. Returning to the present he discovers that his momentary interruption has not only had unfortunate consequences for the trampled butterfly—its death—but he has come back to a very different world, which has spun far off its previous orbit. We cannot know the position and spin of an electron (or a butterfly, in this case) at any given moment—I knew that when I decided to go to Astrakhan. I trampled on the order in my life more and more often, straying farther from the path each time: the Caspian Basin, for example, was almost on the complete opposite side of the earth from my birthplace. Even if nothing had made me think I would wake up someday believing I were a butterfly dreaming it was a man, I still have to worry about breaking some law and getting stuck here, alone on the delta of the Volga River, on an island swamped by a rising tide, slipping and sliding into outer space, penetrating the night like a sounding device that was sent out to photograph Venus, or a few hundred kilometers of its surface, the Venusian seas, obtaining images of unsurpassed beauty and then going too far, and unable to correct its course, flying over Saturn, beyond all hope, to discover more heaps of dust, new rings, all useless, all destined to be lost to the world and its people, to be swallowed up forever in the galactic night. As I passed across Istanbul, V. saw my solitude, and I was saved, caught by the heavy mass of a woman who drew me with the full gravitational force of her belly dance, her omphalic wisdom. The letters she sent me were like new directions, page after page, the binary sequence I needed to correct my course.

Why had I traveled to Stockholm (and then later to Istanbul)? To get rich. Inspired by base instincts yet again—I should write that down, to explain to V., and to myself, how I had arrived at that table in the café in Istanbul. The account I gave of my travels at that time was quite brief and largely false. Now I could describe them in detail, scrupulously, like an eye following the sinuous Cufic writing on the doors of some Tartar houses (the Tartars from Khanato in Crimea) here in Livadia. In her second letter she told me about her trip back: how she traveled across Russia to get home, how her mother clapped her hands to her cheeks, speechless with amazement. I should begin with the trip that brought me to Istanbul, the chain of purchases (and sales); list the transactions that eventually led me to that café by the Saray, the nightclub with exotic dancers and strippers.

Because before the butterfly business, I had sold glasses for seeing at night (natt kikare, in Swedish). And before that—just to give her a sense of the turbulent atmosphere in Russia at the time—I told her I had laid eyes (and hands) on the skins of Amur tigers, on the endangered species list; the tusks and teeth of mammoths, preserved in the permafrost on the banks of the Liena, in Yakutiya; new antlers from young reindeer (for months my refrigerator held a bottle of blood obtained when the horns were sawed off, blood that had medicinal properties, scientifically proven); also snake venom (from the Karakorum desert in central Asia); and red mercury, a mineral no one had seen before, worth hundreds of times its weight in gold. On one occasion I was contacted in Tallinn by a potential buyer, a Scotsman, redheaded and red-blooded, with a dagger in the bag he wore over his kilt, not a knife, but a dirk, which he pulled to intimidate me: he wasn’t going to fall into a trap in Russia, so far from Scotland. It’s not so much whether you deal (obey the laws) as what you deal (maximum gain with minimum risk).

My list—the preceding one—is considerably shorter than Amerigo Vespucci’s. Did V. know (no, of course not, I’d just learned it myself) that the continent where I was born owed its name to a letter, one Amerigo Vespucci sent to Lorenzo de Medici in 1501? I’ll copy his list, Amerigo’s merchandise, for the sake of comparison. Here is what the Italian wrote, his mouth watering: “The aforementioned ships carry the following: They are laden with immeasurable cinnamon, fresh and dried ginger, abundant pepper and cloves, nutmeg, mace, musk, civet, liquidambar, benjamin, purslane, mastic, incense, myrrh, red and white sandalwood, aloe wood, camphor, ambergris, sugar cane, much lacquer-gum, mumia, indigo, tutty, opium, aloe hepatica, cassia and many other drugs that would take too much time to record … I do not wish to go on because the ship does not allow me to write.” You see, behind every voyage of discovery is hidden (that’s it! hidden!) some low motive, a little spice and “immeasurable cinnamon!” All I had wanted was to make a little money, a small fortune, just enough for a modest palace, a couple of balconies, some grandly appointed rooms, where I could live in style. At night, as I passed through my billiards room, I would pick up the cue, idly run a few balls, then go out to the balcony and stare off at the horizon, penetrating the darkness, cutting through it smoothly, like a warm knife through butter, or those night-vision goggles, the kind helicopter pilots use, with a thousand-meter range, which would also come in handy for observing the flight of certain nocturnal butterflies, their iridescent wings.

“In total darkness, Herren, the lenses in these goggles pick up the very lowest rays, invisible to the naked eye, a wavelength below infrared. Behind the lens the photons are focused and then accelerated by a high-voltage current. Hear that faint buzzing? Same principle as a television, cathode ray tubes. The photons are propelled onto a phosphorescent screen, agitating it, creating the image on it. Like this. You look through here, through this opening. No, you can’t see anything, because it’s not dark yet. It’s turned off. No. Impossible. It would burn out. The photon current is very strong this time of day, bright as it is. Your eyes would be burned out, permanently damaged, like a man who’s been in prison for years. Gets blinded when he’s let out, his retinas ruined. Actually, that’s what I just explained … A steal like this and you stand here trying to make up your mind!”

“With these goggles you could go out on the Baltic, the high seas, in the dark of night, keep watch for the coast guard, sail to some designated spot, some buoys marked with paint, only visible through these goggles, my cargo floating safe and sound in a watertight container …” He was thinking out loud, the smuggler who bought the first pair from me, a Pole, pushing a lock of blond hair off his face, a gesture that would allow me to identify him later, in case of trouble, a grilling from customs agents.

“Or you could spend as much time as you like spinning the dial on a safe, again in perfect darkness, your ears tuned to the click of the correct combination, or else stand and watch your prey, man or animal, through this scope, attached to a high-powered rifle, using this silent lantern to light the scene with infrared rays, invisible to the naked eye …”

I was pointing at a battery of gunsights made for the assault troops of the Russian army. But the Red Army was now completely bankrupt, infantry, motorized, aerotransport units all liquidated, selling their privori nochnovo videnia (night-vision equipment), top quality but ten times cheaper than Western stuff, a price difference that gave me a nice profit margin.

I lost count of the trips I made carrying this illegal military equipment, traveling to Hamburg, Vienna, Amsterdam, Stockholm, so many other northern European cities, feigning sleep during customs checks at 3 A.M., enduring dozens of searches that didn’t get to the bottom of my deep bags. I had passed through the smoking ruins of the Eastern Empire, from Varsovia to Cracovia, from Buda to Pest. And in the best plazas of those capitals, I had learned how to spot a buyer a long way off, to pick one out of the slow parade of passersby inspecting the merchandise suspiciously. The Swede I saw come around the corner one afternoon, walking toward me, smoothly slicing through the sea of heads—his walk, his bearing, gave him away. I broke off my pitch, wasting no more time on cash-poor gawkers, I practically pushed them aside, clearing the ground for this man with a pile of crowns in the bank, a BMW owner, but not flashy, dressed in a worn overcoat and cloth cap. After just a couple of questions, he picked up the goggles to take a look (but didn’t get one), a ring inexplicably dancing on his finger (thick as a Viennese sausage), which told me right away that his overcoat held a checkbook, and that he was going to buy them.

He took his eyes off the goggles and raised his eyebrows, sure my answer would be close to the sum he was secretly willing to pay. No fear of a trick: the price I asked for the goggles eliminated that possibility. I told him how the goggles worked, in no hurry—not pressured like those hawkers who tell nothing but lies—explaining it in detail (sometimes I even draw a diagram if I suspect the buyer knows anything about the Second Industrial Revolution). I told him about their military origins and brought up the problem of darkness, the very problem the goggles were designed to solve. The man in the cap, a large heavy gentleman (like a Viking), interrupted me: “Will you take a check?” and before I said yes—with no doubt in my mind he could cover it—he started to reach toward the inside pocket of his overcoat, only to have his hand pulled away, by two mastiffs tugging on a leash. No problem, the deal was far enough along. I was feeling relaxed, almost friendly toward him—he had shown confidence in me and I in him. How sweet it is to close a deal, watching the fountain pen smoothly inscribing the specified amount (no small sum, that’s all I’ll say) and figuring how much more it is than the price I paid just a few weeks ago, not too far from here, at the dark edge of that garrison, at the hour I had chosen for testing the goggles, quickly focusing them on a little patch of woods across the highway, afraid of getting collared, and then ripped off, by second lieutenant Vinogradov, an official who was making a killing on the illegal sale of Red Army equipment. A man with a pack was coming toward me through the woods. Suddenly I saw him stop and look up, staring right at me, standing outside the garrison wall. I lowered the goggles and couldn’t see a thing; it was pitch black; the man couldn’t have seen me either.

The Swede, Stockis was his name, wrote his phone number on the back of the check, so I could call if I had problems at the bank, if the teller pressed the alarm button surreptitiously because of the incongruence between the clarity of the figure stamped on it and the opacity of my non-Nordic eyes. It may have been a mistake, but I trusted this man who was walking off with my goggles under his arm, pulled along by his dogs. So I brushed off a curious guy, one of those browsers with nothing but questions: “Could you do me a favor and keep your hands off?” I bellowed. Tyrannical as any Moscow shopkeeper, I was already gathering up my merchandise, sure there’d be no more buyers today. One more lesson: always leave after a big sale, there’s never more than one a day.

I still hadn’t cashed the check two days later. The paper lent a certain immateriality to my sale, a certain flash of intellectual effort that would fade when it was exchanged for cash, reduced to the singularity of a few bank notes, the biggest ones they have in Sweden, it’s true, the same bills, I thought, that King Gustav got paid in, if a king would bother … Well, haven’t we all learned the surprising fact that Olof Palme goes to the movies just like any ordinary citizen? Those bills with Selma Lagerlöf on them—Gustav could well have held them in his hands.

Five days later, when he came back to the same spot on the plaza, I showed him the check. He liked that.

I had decided suddenly to change the course of my life, to take to the sea. I had spent nights in railway stations, covered thousands of kilometers by train, made five plane trips in a week. Now I found myself steering a yacht through the maze of islands around Stockholm, at the invitation of this great big man, a Viking with a gold hoop dangling from his ear. We were headed to his house to discuss a subject that needed a place like this, covered with pines and completely surrounded by water: an island.

We docked off a narrow pebble beach: water quietly lapping against the rocks, wind whispering in the pines. I jumped down from the yacht. Stockis had a proposal, he had said, something that might interest me. And while we went up some wooden steps to a terrace overlooking the beach:

“On dark nights I come out here and keep an eye on my yacht with the goggles you sold me …”

“Are the dogs yours?” I shot back quickly, because my English wasn’t up to the circumlocutions of normal conversation, forcing me to latch on to a subject directly, like a mute. The blunt question stood for this long speech: “You have two mastiffs, don’t you, the spotted ones you had in the plaza, so why do you need night-vision goggles to guard your property? You may be fabulously wealthy, you certainly seem it, but isn’t that rather extravagant?”

Stockis had been to China (and in China, to Manchuria); I mean, he’d been around, all over the world, and he obviously knew how to carry on a conversation, however rudimentary the English. He came back with an explanation.

“You can’t even see your hand in front of your face some nights here in Stockholm. It’s dark by three in the afternoon in the winter. I don’t think you could have picked a better place to sell these goggles. I have a yacht and don’t sleep well. Sometimes I get up early and watch the sunrise from this terrace. But come, we’re not here to talk about that …”

We went into the house. Through a service door in the back. On the kitchen table I saw food-caked dishes, a half-eaten box of chocolates, candy wrappers all over, as if there’d been an explosion. We went to the study, down a hallway littered with beer cartons, stepping over ads for pizza parlors with Swedish names, with the mastiffs (which did belong to Stockis) nipping at my heels. The mess suited me fine, I’m the same when I’m home alone and end up drowning in magazines, pants, shirts I can wear one more day, clean enough, hung on the backs of chairs, glasses still holding the dregs of tea, but on top of it all anyway. I know what it’s like to let myself go, to slide down that slippery slope of slovenliness. Between trips I often find myself watching television, which I detest, until four in the morning, a book open in my lap, bored by whatever’s on, knowing the bad cop will betray the good one several dull speeches before it happens. And never anything about smuggling, there’s almost never a show with anything about smuggling, much less smuggling bugs or butterflies.

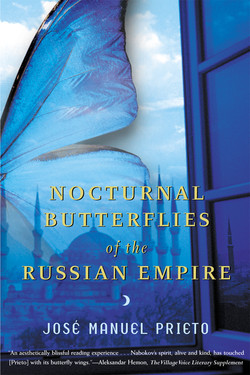

“Russia has several rare butterflies, extinct in the West …” he began. “There is one type in particular, the yazikus, which lives only from the end of May to mid-September. I would give everything to possess it.”

“Everything is not anything,” I replied, and then, to his broad chest, “How much?” because I do not believe in a numerical infinity, which I consider an intellectual concept, nothing more.

“Stockis is also a trade name,” he said, as if confident this would add some weight to his proposal, but not explaining why. I had followed him into the study, preceded by the panes of the plaid lumberjack shirt stretched across his broad back. When he turned to see what effect this revelation had on me, I climbed up on tiptoes and peered over his shoulder, to expand my field of vision. My gaze slid along glass display cases hung from every wall. There was just one window, in the north wall, and, on both sides of it, innumerable cases full of butterflies, glowing with a soft light.

Sure, we were here to look at butterflies, and for him to propose some deal with butterflies, I knew that, but he could still have some other field, and I said, “So, you have a business … that sells … ?”

He stopped in front of a case and tapped the glass, answering me without saying the word “butterflies.”

“I will be sailing to Istanbul at the end of May, on the Vaza. I have clients in the Middle East who are going to meet me on an island, on Crete, but before that we can look around Istanbul, you and I. Have you ever been to Istanbul?”

I had not been to Istanbul.

From floor to ceiling, up to the rafters, the study walls were covered with cases full of butterflies, which were held down, I noted, with round-headed pins, easy to get hold of. I did not know a thing about butterflies at the time, on that day near the end of winter.

“No questions until they make the first offer,” he lectured. “That way, you’ll know what kind of number: tens, thousands, tens of thousands. There are innumerable orders of butterflies. If a collection has specimens from a single order, it’s no good. It’s worth much more if it contains examples from various orders, organized lowest to highest…. By the way, there’s a forest in Finland, near Carelia, planted by the Russian army for the production of masts. A friend of mine got the mast for his yacht, a sailboat, there … I don’t know Russia. But they say it still has some yazikus, butterflies that are worth a lot of money” (or did he say “a fortune”? I don’t remember). “And they say Czar Nicholas II was the last person to capture one. He was the last czar, too, right?”

(Who says? I felt like asking Stockis, who told you that?)

He was thinking, about to add something, maybe about the offices the Nobel brothers had in Baku and St. Petersburg, but out came:

“Wait,” he struck the arm of his chair, worried, and asked me: “How will you recognize it?” like in some detective novel, so that I pictured myself waiting in some nightclub or restaurant, with a copy of Botanic World Illustrated spread out on my table. But I wouldn’t have any trouble identifying the insect: it would show up for our meeting with a green umbrella tucked under its right-front leg, in outsize boots that rattled around on its last pair of tiny legs. And it would have its wings folded, so that if not for its skinny thorax it could have been some flashy cowboy in a sunflower overcoat.