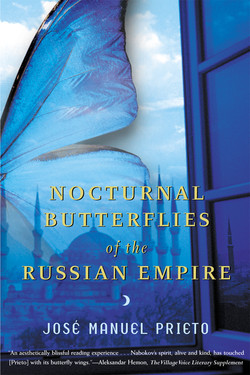

Читать книгу Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire - José Manuel prieto - Страница 16

4

ОглавлениеCASPIAN BASIN

We would land somewhere between the mouths of the Volga and the Astrakhan. Traveling through the tangle of the delta’s canals in a coastal steamer, I saw the Caspian as an empty wineskin, with the steamboat dropping down into it through the narrow neck. I would leap ashore, into a patch of reeds in some spot not marked on the map, and a week later I would be at some other beach waiting for the same steamer, which would take me home, fabulously wealthy, my saddlebags stuffed with rare specimens.

But first I had boarded the boat in Astrakhan, at a dock so full of barges that it looked to me—viewing the countryside from the heights of the city—like it would be possible to walk across the Volga without ever touching the water. I began my descent to the dock down a poorly paved street, positive I was headed in the right direction because a thin stream of water was running down-street, too, trickling along the edge of the sidewalk. That water could hardly be wrong about the way to the Volga, from which it had so recently ascended to heaven, then fallen to earth again and been dammed. Deep in a cold storage room someone had opened the tap, I thought, like releasing a bird to return to the woods, and the water now led me to the Volga: flowing along, following the course of gravity. I stopped in the middle. Water swirled around my heels and I felt a chill from deep in the Volga through my leather boots. In a shed near the shore, some workers were stacking barrels of pickled fish. I got within twenty meters of it and was about to ask how to get to pier no. 5, where the steamer was docked. I had already taken a big breath and picked out one of the workers—the man standing in the doorway of the shed cupping his hands to shield the flame of a match, who would raise an arm when he caught my question and point either to the right, fifty meters beyond the shed, or to the left, past the building with the barred windows—when I saw the sign myself, nailed to the top of a post, over the head of the worker, almost scraping it: “River dock no. 5,” written in rustproof paint. The man finished lighting his filter-tip and went back in the shed.

The low light at that hour made me look even more like a criminal, a sturgeon poacher, a member of one of the huge gangs trafficking in Caspian caviar. The steamer let off dozens of silent men who tossed their packs ashore and then jumped after them surefootedly and took off without a backward glance, their sights already on the banknotes snaking through the reeds. I didn’t turn back either. I moved toward the riverbank feeling the eyes of the captain on my back. My equipment differed considerably from that of a sturgeon fisherman, but I chose not to disillusion him. He would not have believed me anyway, even if I spread the contents of my pack on the cabin floor: no clubs to stun the poor sturgeons, nor curved knives to slit their bellies: just flasks of ether, two butterfly nets with adjustable handles, an acetylene torch for night hunting, and an inflatable rubber boat, to cross the delta’s numerous waterways. V. V. Sirin’s Diurnal and Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire says two yazikus were captured in one of the fields in this delta, in the Caspian Basin, in 1893.

Standing in the reeds, I saw the steamboat move away. I watched it back up, testing the depth of the river with its propellers, then straightening its course and continuing its trip.

By eleven that morning I was on the edge of a field, dark green with hundreds of butterflies floating above it, but no yazikus in sight. The heat kept intensifying, rising gradually, like the sounds from the orchestra pit at the opera. Without daring to leave the protection offered by the trees, I opened Diurnal Butterflies and flipped through it like a conductor glancing over the score one last time before striking the music stand with his baton. None of the butterflies paid any attention to the stick (of my net), which I slowly drew out after five minutes scanning the book, trying to match a butterfly from the page with the one that landed a few inches from my eyes, on a branch. When I found it at last, a common colias, I waved my net, desperately hoping that the butterflies would synchronize their flight across the field, get into formation, glide along the ground, rise in a loop-the-loop, pair up to waltz past me, prettily, then get in line and drop into the bottles of ether, one per bottle, with me cavorting joyfully, like a faun, blowing a panpipe, sealing the bottles, holding them up to the light, admiring each specimen before setting it in the bottom of my pack.

The music (Disney) disappeared as soon as I swung the net, missing completely, and started racing around the field, in giant strides (Chaplin), scaring off the colias, streaming with sweat, and getting stung by mosquitoes—they were nowhere to be found during the waltz of the butterflies, but when I stepped into the grass, breaking the luminous skin of my field of dreams, they swarmed up and rushed toward me like a group of ugly actresses, with no talent, mobbing the producer at a casting call, hoping to win the role of Sleeping Beauty. Dying to go to an eternal sleep at the bottom of my ether bottles. I had to postpone my career, start hunting mosquitoes, an easy job, slapping. They died without having sucked my blood, empty, insensible. The colias, more peaceful, came back and landed on some nearby flowers, to tempt me.

The Volga was shining through the trees: I could always leave this island, throw my rubber boat in the water, let the current carry me along. I thought of Stockis. Not cursing him, simply thinking he was the only person who could make sense of the mosquito bites and sweat running down my spine. To me they were just butterflies: I had no idea how to exchange them for holidays on Niza, books or oil paintings. The design on their wings held no interest for me—unless it earned some real interest. I needed an expert in the field, an experienced hunter, but then I’d have to split the profit.

I saw one right next to me, exploring a flower with its delicate feet. Not a yazikus, but I hoped that focusing on a single specimen might save me from despair. I followed it all over the field, past lots of other butterflies that I could easily have had, ignoring them because if I lost sight of it, if I wandered for a moment, I’d be doomed to chaos, the dozens of colias flying over the grass sipping nectar from the flowers. I took my time, trailing it like a hunter after a hare, matching its zigzags step-for-step in an attempt to wear it out. I saw only the shifting backdrops that framed the desperate beating of its wings, small squares of sky, grass, trees. Sweat dripped from my eyelashes, but I didn’t raise a hand to wipe it away, obsessively wielding my net, moving forward. I caught a glimpse of the steel belt of the river. Refreshed by the breeze, I cut through the trees, the flashing point of its flight leading me on.

I had seen too many movies to not see myself, running forward exhausted, sawed-off Colt in hand, ignoring the small-time crooks, pursuing the arch-villain, who’d given me a deadly look before the chase, before fleeing the scene of the crime, police cars closing in, sirens wailing. The sand slowed my pace, the breeze checked its flight: a gust of wind forced it to fold itself against a tree trunk. I pounced with the butterfly net, pulled tweezers from my pocket, and seized it: the glint of the steel, the enormous hand, gigantic, it threw me one last terrified look and hid its head between its wings, its fear reflected in the thousand octahedrons of its eyes. Glazed over.

I raised the flask and held it to the light. The breeze blowing off the river finally dried me off and I called it quits, staring at the silhouette of the other island covered with pines, which seemed to be floating past, carried along by the current.