Читать книгу Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire - José Manuel prieto - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеST. PETERSBURG

It was raining in St. Petersburg. The city was suspended from the sky by dark gray threads that melted onto its sidewalks and zinc-covered roofs. I caught a cab at the metro entrance, and we drove down Nevski, through raindrops spattering on the asphalt. I told the driver to let me out on Liteinaya, the booksellers’ street. I wanted to visit Vladimir Vladimirovich, an elderly gentleman always bent over a book, his back to the bookstore’s main room. Which was in a small cellar beyond the sound of the rumbling streetcars; you got to it through an arch that opened onto a patio with crude bars on the first-floor windows and drain pipes whose ends were cemented to the ground by silver icicles. The basement was in a second patio—there was also a third, through which you could exit, escape to the next street if necessary—behind a door covered with layers of pasted-up signs. They were the work of the girl who watched the cashbox, the girl I had discovered one afternoon passing a colored pencil over a plastic stencil of the alphabet. They ran because of the constant humidity in St. Petersburg, which soaked right through them and even dampened the pages of books that sat too long in unheated basements. Like the copy of Diurnal and Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire, for example, which I found on a shelf near the door. In the same room one afternoon I found a book that I didn’t dare return to the shelf once I held it in my hands and leafed through it, that I kept clutched to my chest, exultantly. I remember it perfectly well but won’t say what it was. This had to be the best bookstore in St. Petersburg, which at the time was called Leningrad, an ugly name. So when my new business interests forced me to embark on a preliminary study, following the trail of the yazikus through the Public Library and the used bookstores, I remembered this man, who spent hours—the time I lost sniffing around the shelves—bent over a book, like any other customer, even though he was actually the owner, the principal investor, so to speak, in the bookstore, and Liena, the girl with the cashbox, who colored a new sign for the door every few months, always switching the store hours. Later I learned that these changes reflected the hours she closed to meet her lovers, with their various occupations. She took me, for example, to her house, which was close by, in the Fontanka, from 1:30 to 2:25, and then closed at 6:00, even though it was spring, and the days were getting longer, so there were still customers at 7:00. The old man, I remembered as the door opened with a jerk and warm basement air hit me in the face, was named Vladimir Vladimirovich. I had never spoken to him, but Liena often complained about him after the short midday break in her room, half dressed, throwing on her clothes, pulling up her stockings, putting on makeup at the mirror, bra straps cutting into her back: “Vladimir Vladimirovich is going to kill me. I can’t go on like this, always getting back late, changing the hours. You know though?”—and she sought my eyes in the mirror—“He doesn’t even notice. He has tea and biscuits in his office, never comes out till closing time. God, he must be eighty years old.”

I found him in his office sipping tea from a discolored cup that could have come from an imperial service.

“Vladimir Vladimirovich! I don’t know if you … Look, I have a job. A Swede, a rich man, has hired me to capture a butterfly, a rare specimen. I’ll tell you the whole story if you have the time … Do you know that in Finland they still have stands of pine grown for masts, with thick trunks, no twists? Of course you know that: I’ve read it, too, actually, wait … Right, in a book I bought here a few months ago. Peter had them planted, but by the time they were big enough, fifty years later, there was no use for them. But no, that’s not true. They were still making ships with masts. Even today there are a few left, old-time ships … No, I had some before I left home … Okay, one cup … I was just considering a catalog of butterflies that you have. But maybe you know a better one. Yes, you’re right, a butterfly that’s almost extinct, what book would that be in? Thanks, Vladimir Vladimirovich. It seems I’m going to the Caspian Basin and from there to Istanbul. I have some books I’d like to leave on consignment, for you to sell. I’ll stop by before I go.”

Talking to Vladimir Vladimirovich, into his big octogenarian ears, made me nervous. We had never had a real conversation. One day he told me that he was planning to write a book about Nevski Avenue, about a house on Nevski, number 55. The one that has some dancing birds, griffins, a pattern, you know, from Scythia. That’s right, was all he said. He never lingered on the salient points in my remarks, like he did on the winged griffin, the animal motifs of Scythia. I hadn’t told him what I did (at the time I was moving sides of beef in a packing plant on the edge of town, awful, terrible pay). I had never seen him outside this store, behind his stands. One afternoon, it’s true, I saw a very old man, in a moth-eaten greatcoat, crossing Liteinaya, just about caught between the tracks as two streetcars went by. He managed to get through first. Vladimir Vladimirovich had never asked me, like the police, for example: “And you, young man, where are you from?” That was a subject completely immaterial, irrelevant to him.

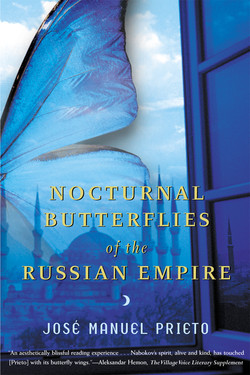

On the same thin stiff translucent paper that he used for labels (writing the names of his butterflies on narrow strips in India ink) Stockis had copied down the distinguishing marks of the yazikus, in English, in the neat hand of a professional clerk. Wingspan: 30 to 40 millimeters. Wing pattern: dorsal, pale yellow background with a pattern of angry eyes, a defense mechanism, inspiring the concept of danger in its predators (this unnecessary explanation and the ticklish term “concept” puzzled me). The description I found in Diurnal and Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire, by V. V. Sirin, was less “psychological,” more nineteenth century (St. Petersburg, 1895). It agreed for the most part, but the ink drawing by Rodionov, S. V., illustrator, was clearly superior to the photographs in modern catalogues, like Stuart’s.

He used the same paper to explain how to preserve the specimen if I should capture it. First I should kill it by putting it into a wide-mouthed bottle full of ether, being careful not to touch the wings and spoil their fine iridescent powder. Once it was dead, I should pick it up by the thorax, the top part, and fasten it horizontally, somewhat loosely, so it could be moved when it was in the collection … He broke off in the middle of the instruction. Put two thick lines through it. Resumed more confidently, taking a different approach, from the word bottle. Use it to carry the captured specimens (now plural), so they would not get dislodged and damaged during transport. From where to where? I thought. We had spoken of only one point: Istanbul. He would prefer that the sale occur there, rather than somewhere too dangerous, like Russia, since the violent explosion of the mafia, or too safe, like Sweden, where the cops could not be bribed: forget Sweden.

I bought a Handbook for the Young Insect Collector, too, for a thirtieth of what I paid for Diurnal and Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire. I thumbed through it right there in the bookstore. How to prepare a mount. Materials needed. The insect or butterfly net … It’s better to make your own net … I didn’t have time for that. I bought one with an adjustable handle, the kind they sell in Yuni naturalist stores (for “The Young Naturalist”: me, for one).

At last I had my hands on a detailed description: it lived in sunny open spaces, border areas, its wings deeply cut on the outside edge, two series of submarginal spots, bright yellow. A verbal portrait complementing the photos from Stockis and the beautiful illustration in Diurnal Butterflies, a full-page vellum sheet, behind which pen-and-ink butterflies seemed to be flying in the morning mist, or just the way I saw them now, through half-closed eyes, lying on my back in a field in Livadia, only half-looking, sure that yazikus were long gone: whether killed by DDT, intensive farming, or seventy years of Soviet rule.

The Natural History Museum would probably have one on display. I had studied every detail of the yazikus picture: the tiny legs that the illustrator must have painted with a fine sable-hair paintbrush, the antennae … they were engraved in my mind all the way there in the cab.

Still inside, I stared out at the streetcar landing by the Winter Palace, at the women with raincoats and umbrellas rushing to board the trolleys. I began the climb, my black shoes glistening from the rain against the horizontal gray lines of the stairs going up to the museum.

Leaving behind the moth-eaten bones of mammoths, their skeletons clumsily resting on bony feet, unable to take flight, I began the dizzying descent to the winged simplicity of the lepidoptera. Right at the door, eye-catching, a huge example of Lepidoptera fenestra. I drew closer to look, pinning it down in the middle of the multicolored flutter in the other glass cases, the silent flapping of the vanessas.

There were no yazikus on display. I carefully checked all the little labels, straining to bend over them. I seemed to see a reflection of myself in a low genuflection, but quickly realized it was a live specimen of the local fauna, a little old attendant, slowly shifting in her chair in the corner, her soft cheeks puffed out by the gob of caramel she was sucking placidly. I stepped forward to look at her face. Her eyes were shut and she seemed asleep, but her jaws kept working automatically. She did not open them when she heard me talking to her. Just stopped sucking since the interior roar from that activity isolated her sonically from the room: Ya slushayu Vas (I hear you). I asked to see the yazikus: she was as slow to answer as if a team of stagehands had to roll back the tarpaulins and pick up the instruments that an orchestra had left in the rain at a summer concert. She blinked, opening just one eye, and studied me for a moment: “There is no such thing. I have never heard of such a butterfly. Who said we had one here? Konstantin Pavlovich … Well, he is not here today … Our nauchni (scientific) konsultant could explain it better, but he has Sundays off. He gave me strict orders … I mean, there is no such … If there was one, wouldn’t we have it here, in the best museum of entomology in Russia?”

The whole time she spoke she was darting back and forth in her chair, peering around, trying to watch the corners behind me, since I could be part of a gang, the one who keeps the guard busy with friendly chatter while his accomplices ransack the display cases. After all, museum robberies were on the rise in Russia. But it never even crossed my mind to steal the yazikus from the Natural History Museum, even though it would be a lot less work and a much shorter trip—a few trolley stops from my home—than organizing an expedition to the Volga delta.

That trip held the opposite appeal: tramping around in my tarred boots, hiking through the trees. If the Russian state, in the person of some anonymous hunter, had gone ahead and bagged a couple of specimens of yazikus for its collection, then I don’t see why I should have to get them by force, stealing them instead of winning them honestly, playing by the rules. I had had no plans to use a handkerchief soaked in ether on the old lady who had been so slow to open her blue eyes, eyes that were strangely bright, probably in mint condition from how little work she gave them. But she was sure I was a foreign occupier, she’d seen plenty of movies about partisans, and during my interrogation she had to lie at any cost, even her life; so she just kept talking, that is, zagoborit menia, misleading me with aimless remarks, denying any knowledge of where the weapons were hidden, or the yazikus, those were her instructions, she had gotten them from Konstantin Pavlovich, the konsultant: “Nadieshda Ivanovna, you know that this is a terrible time for our country. We have been hit by a crime wave, youthful crooks attracted by our wealth, anxious to enrich themselves, as you well know. This new tide comes from the West. They will ask about certain specimens from our collection. I will mention no names because then you can’t remember them. This is all you need to know: deny everything. You know nothing. The specimen they want does not exist; you have never heard of it. There is one butterfly in particular … But no. You only have to say (playing dumb, you know): No, I don’t know what you’re talking about. Yazi? Kuz? Well, no, never …”

It was obvious she was lying. She was agitated, like a person not used to it. She kept rocking in her chair, as if an accomplice behind me was busy filling his sacks. Not too long ago, some thieves—very polite, attentive young people, eager for knowledge, like so many previous generations of pioneering youth who had toured the museum in big groups, totally innocent in appearance—had come into one of these rooms and stolen some mammoth teeth. I had read it in the newspaper before I left for Helsinki. I did not, however, draw any practical conclusions from that item in the Sankt Petersburkie Vedomosti. True, there was no reason for such considerations at the time, when I was at the station, waiting to board the train to Helsinki, but when Stockis gave me a list of the butterflies he wanted, and I decided to visit the Natural History Museum, back in Petersburg, it had not yet dawned on me that the Volga expedition was completely unnecessary, since the specimens Stockis wanted were all in that museum, caught by the long arm of the state, conveyed from their far-flung confines to the former capital of the empire and confided to the feeble custody of a frail old lady, easy to knock out with a handkerchief soaked in ether. Instead of knocking out dozens of butterflies, that is, moving tortuously across the irregularities of the map, burned brown by the sun, breaking ground in my hob-nailed boots, I could reduce my ether overhead to the few drops it would take to put this old crone to sleep and then board the trolley outside the museum, blending in with the raincoats, and cross the city on the bus. Much shorter, and much safer, than a trip to the Caspian Basin.