Читать книгу So Few on Earth - Josie Penny - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 Before Memory

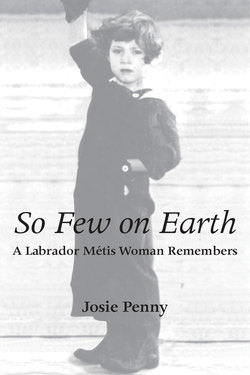

My family lived a primitive and extremely harsh existence where only the strong survived. I was born on January 15, 1943, in our winter home of Roaches Brook, Labrador. Mom decided to call me Josephine Mildred. My eldest brother, Samuel, was born out of wedlock and was adopted by my father when Mommy and Daddy were married. After losing their first daughter, Sivella, from unknown causes, I came along, third in line behind my sister, Marcella. I was blessed with good health, strong bones, olive skin, hazel eyes, and curly blond hair. strong bones, olive skin, hazel eyes, and curly blond hair.

“What was I like, Mom?” I asked many years later.

“Ya was beautiful, maid. Yer little head was covered wit yellow ringlets dat hung down round yer shoulders. An ya was a good baby, too. But yer lucky ta be alive.” She rocked back and forth, her eyes gazing far into her memory.

“Why?” I asked.

“Well, maid, ya was a happy, carefree little ting, always runnin about and gettin in de way. Ya shoulda been dead long ago!” As her eyes glazed, I knew what was coming, and I never grew tired of the story.

Mom settled back to tell me the tale of how I was attacked by husky dogs. The fire crackled, throwing shafts of light on the wall. Her voice grew dreamy as she spoke of the faraway times. Her story went like this.

We were living in our summer home on Spotted Island, a rocky place in the North Atlantic. My family went there every summer to fish for cod, our livelihood and a staple in our diet. On the island, children and dogs were able to roam at will. The dogs were free of harnesses and chains. During warm summer days, they lazed underneath the houses where sea breezes kept them cool.

To shop for supplies and food, the island residents had to make a run to the mainland by boat to Dawes Store in Domino. The sea raged constantly, and there were times when some of our people starved to death because they couldn’t get off the island for supplies. Often they had to wait for days or even weeks for the weather to become civil enough. That summer, when a calm day finally arrived, my mother left us in the care of Aunt Lucy, a neighbour, boarded a motorboat along with several others, and headed across the water.

I loved the new puppies that were born each spring, and being inquisitive I wanted to see them, so I meandered along the rocky path, munching on a slice of molasses bread. Unfortunately, I fell. The husky mother saw this as a threat to her litter and attacked me. The other huskies, always hungry for food, took advantage of the situation and joined in. I started screaming. Aunt Lucy heard the commotion and ran out. Her broom high in the air, she swiped at the dogs. Everyone within earshot dropped what they were doing and raced to the scene.

In just a few seconds I was mangled beyond recognition. There was panic and confusion. Seeing my grave condition, someone wrapped me in a white bedsheet, which soon was red with blood. They couldn’t tell at first how badly I’d been hurt. But on closer inspection they saw that all the flesh was torn away from the back of my head, exposing my skull.

As soon as the boat landed on the stagehead, my mother dashed up the hill. Everyone tried to shield her from the horrible sight.

“No, Flossie, don’t look!” they all cried.

Immediately, my mother realized that her worst nightmare had come true. Moaning and groaning like a crazed person, she grabbed her child and removed the sheet.

My mother came out of her reverie at this point. “I’ll never forget what I seen dat day. It’ll be in me mind ferever!” She shook her head, hesitating for a moment, then continued the story.

“As de boat got closer, I could see dat sometin awful happened wit de dogs. Lots of us had problems wit dogs before, so I was scared ta death! As I climbed de stage, I knowed t’was bad. People was screamin and cryin! As I ran up de hill, I could see someone was wrapped in a big white sheet, and it was completely red wit blood. Everyone tried ta stop me from takin ya. Dey tried ta shield me, but dey coulden. When I took de sheet off and saw yer little head, I fainted.”

“What did you do then?” I asked.

“Soon’s I come to, I knowed I had ta do somethin quick! I picked some juniper boughs, boiled ’em, and mixed ’em wit bread ta make a poultice. I put ’em on yer open cuts an bandaged ya up. I did dat fer t’ree or four days, till de steamer come and took ya ta Cartwright ta de hospital.”

Sarah Holwell, a Spotted Island resident who was working in the Cartwright hospital at the time, had come home for a short visit. She was asked to accompany me to Cartwright, about 60 miles away. We travelled on Dr. Forsyth’s schooner, the SS Unity. He was the resident doctor living in Cartwright then.

“What kind of shape was I in?” I asked Sarah many years later.

“Ya was some sick, my dear,” she said, “but ya was alert. Ya didn’t jus lie there. I changed yer dressing in Table Bay when we stopped fer the night and yer head looked terrible! We didn’t have any medicines or anythin! But ya didn’t cry much atall, just whimpered a little through de night. I’d seen dog bites before, but yers was de worst I’d ever seen.”

“How long was I in the hospital?”

“Oh … bout a month, I tink, but ya was a tough little girl. And I remember yer beautiful blond hair. Dey took a razor an shaved it all off.”

According to the story, when I arrived at the hospital in Cartwright, the doctor discovered my mother had done such a good job of dressing and treating my wounds that they couldn’t sew up the badly torn flesh. It had healed too well, so they decided to treat them as they were. Dr. Forsyth told Mom that my skull was too exposed and that a skin graft was needed to cover it.

“I’ll never ferget when ya come home. Ya looked so cute in yer little red-and-white polka-dot dress,” Mom told me years later. “But I was broken-hearted because all yer blond ringlets was gone. Jus gone! And now yer hair was real short an dark. Ya looked so different. Not at all like my little blond, curly-haired girl from a mont ago!”

My mother loved to reminisce about our reunion. “Even though ya was spoiled by de nurses,” she used to say, “we was happy ta have ya back home.” Then her tears would flow freely. Every time we had a visitor in our home, she’d gently pull up my hair to expose the terrible scars. Using her index and forefinger, she’d rub along my skull, feeling the deep grooves left by the bites.

“Dese rips on yer head was wider den two fingers,” she told me. “Dere was several teet marks as well as de two big ones dat went right round de back of yer head, but dere was no udder bites on yer body. No one could understan why de dogs only tore up de back of yer head.”

Later, while visiting Spotted Island on his regular trip along the coast, Dr. Forsyth told my mother the details. “The wound that came closest to killing Josie was the fang puncture behind her left ear that pinned her earlobe to her head. And there’s one spot where there’s a piece of skull missing. Both these areas will be susceptible to pain. However she’s a very tough and extremely lucky little girl.”

The community had to destroy nine dogs that had blood on them. Once a husky has tasted blood they can’t be trusted, so everyone knew they had to be shot.

As with children everywhere, accidents were common. The difference in our isolated communities was the difficulty in getting medical care. Often a home remedy had to suffice.

My mother used to tell of the time I fell from Aunt Lucy’s bridge, or verandah, into the slop hole. “Ya was foolin around out on de bridge, maid, an ya fell off an broke yer collarbone in two places.” She shrugged at the inevitability of childhood foolishness.

“What did you do?” I asked her.

“I took an ol’ sheet, tore it inta strips, an wrapped ya up till ya was healed.”

In later years my older siblings painted a picture of their life as it was before my memory. Their recollections offer glimpses into the primitive life of our family.

My sister, Marcie, recalled my father’s gift for song. “One of my favourite memories, when we was small, was Daddy lyin back on de settle. He’d sing ta us from suppertime till bedtime. I loved ta hear him talkin ta his dogs as he was drivin along. He’d talk an sing to ’em de whole time.”

Our winter home of Roaches Brook held special memories for Marcie. “When we moved inta Roaches Brook in de fall, de grass would be all grown up real tall over our heads. We would go an pick de moss from de bogs round de ponds an let it dry. Den we would use it ta stuff de seams of de cabin ta keep out de snow an cold.”

Marcie remembered one day when a hunt went very badly. “One day me an brother Sam was after a squirrel, an de squirrel bit his finger. It held on an woulden let go! He was screamin. De blood was flyin everywhere! I was toddlin long behind him scared ta death! Prob’ly screamin my head off, too!”

My mother and Marcie used to tell me often that Marcie fainted when she was hurt. Once I asked her if it was true. She laughed. “Yeh, ever time I hurt meself I’d faint. De first time I fainted, I was standin on de kitchen table. My finger was all gathered [infected and swollen]. I caught holda it, started squeezin real hard, and said, ‘It don’t hurt, it don’t hurt.’ De next ting I remember is wakin up in Daddy’s arms. After dat, every scrape an bump I got, I fainted.”

I asked about our brother, Sammy, who drowned tragically when he was 19. “Sammy was a good hunter even when he was small,” Marcie told me. When I asked what he hunted (besides squirrels!), Marcie said, “Mice. I member seein a pile a mouse skins on de windowsill. Dey’d be swarmin an he’d catch ’em, skin ’em, dry ’em, an sell ’em fer five cents each.”

I was intrigued by Marcie’s stories and wanted to know more about our home before I was big enough to remember. “Tell me about our mommy,” I asked her once.

“Mom was a good hunter, too. She used ta take off in de mornin wit her short little .22 rifle, an she always come back wit tree or four partridges, or tree or four rabbits. I used ta be lookin up at de hills, an lookin up at de treetops showin up against de white snow on de hillside, and thought dey was de partridges Mom used ta get.”

I asked Marcie if she was allowed to go ice fishing as a child. “Sometimes,” she answered. “I member me firs trout. Minnie Rose [a neighbour] an me went down to de steady [a quiet place in the brook] where we used ta get water. I caught a trout, an was I ever glad! I brought me trout home, cleaned it, an split it meself. Den I hung it up ta dry. I musta been on’y four years ol’ at de time. We had a lot a fun, us little ones growin up.”

And so it is with children everywhere. Even when our parents are struggling to keep the family alive, children can still find fun.