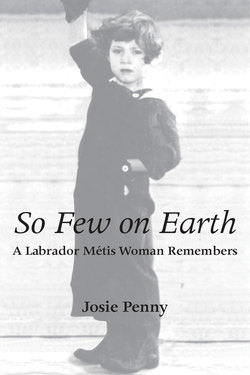

Читать книгу So Few on Earth - Josie Penny - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 Roaches Brook

In the early nineteenth century, as oral history came down to us, two Curl brothers came from England and married Inuit women. My paternal grandfather, John Curl, was a descendant of one of these brothers. Born in 1867, John Curl married my grandmother, Susan (also part Inuit), raised a family of five, and built the largest cabin in Roaches Brook.

I remember that their cabin overflowed with family. In true Labrador tradition all five of John Curl’s family lived at home with their own growing families. My father, Thomas, who was the eldest, had built a little cabin for us so we wouldn’t have to crowd in with our grandparents. Even though Roaches Brook was completely shut off from the outside world for 10 months, the people had everything they needed to sustain them for the winter.

The cabins were crudely built. They were merely tree trunks limbed out and placed together vertically, leaving many seams to be filled with moss to keep out wind and snow. Aside from cabins, the settlement contained a sawpit for sawing logs and a scaffold built high off the ground to keep fresh game and dog food out of the reach of animals. Around each log cabin were an outhouse, a sawhorse, a chopping block, a vertical woodpile, a water barrel, a dog-feeding tub, a komatik (a wooden sleigh), and a coachbox for transporting families on dogsleds.

Our motorboat was chugging along at a good pace as we made our way through the choppy North Atlantic. It was hard to talk above the noise of the engine, and the fumes were so strong that my nose stung. I kept staring at the trees on the hillsides. They passed us by as jagged sentries against the blue of the sky.

“Is we dere yet, Mommy?” I asked, tugging at her coattail.

“Awmost, Josie. Jus round dat point dere. See?” She pointed at a group of hills.

My heart pounded as we rounded the next point. There in front of me in all its beauty was Roaches Brook. It looked peaceful but lonely, with only four log cabins nestled in the shelter of the trees and hills, unlike the rocky landscape of Spotted Island. As we got closer to our landing spot, I could see the tall grass, higher than I was, swaying in the breeze. Although it was only October, the cove had sished over (formed a thin skin of ice). The fragile ice crackled as our boat entered.

Daddy eased the craft into the landwash, trying to keep the dogs from stepping on us as they piled out and disappeared into the grass. Our cabin was the longest distance away, and all our supplies had to be transported by hand for almost a quarter-mile. I didn’t want to carry anything.

“Josie, don’t go empty-handed if ya knows wass good fer ya!” Mommy called out.

Pouting, I grabbed a pillow and waded through the tall grass, bumbling my way along. “Weers ever’body?” I asked, staring up at the tips of the grass. “I can’t see ya, Mommy. Where is ya?”

“Careful ya don’t fall in de brook!” she shouted.

Everyone old enough to walk had to help. It was an arduous job, but after many trips back and forth, we finally finished carrying all our belongings from the boat.

We stumbled, tired and exasperated, into the tiny cabin that was to be home for the next six months. Although there was barely room to move, we were glad Daddy had built us our own cabin.

Everything was done in order of importance. There was no panic or confusion as Sammy and Daddy went about taking the boards off the windows, putting the dogs’ food up on the scaffold, clearing away the land from a summer’s growth of weeds and tall grass.

“C’mon, Josie, let’s go pick de moss!” Marcie hollered.

“Awright den. C’mon, Sally!” I yelled to my younger sister. “We gotta pick de moss.”

Off we ran to collect moss that grew in abundance in the bogs and under the trees. We brought home armloads, dried it, and stuffed it into the seams of the cabin to keep out the wind. Being a free-spirited little girl, I wanted to explore. Unlike the barren hills of Spotted Island, Roaches Brook was surrounded by forest. I stood in awe among the tall spruces, absorbing the wonderful aroma and the sound of the wind whistling through treetops. As I investigated my surroundings, I was fascinated to see willows growing up through the water.

At last all the supplies were put away and we were settling in. Our tiny cabin had two small windows in the front, and a little one at the back. We entered through a tiny unheated porch that served as a freezer. Dog harnesses, bridles, and traces hung on nails on the walls. The main room contained an old “comfort” stove, a crudely constructed table, a bench, and a couple of rickety chairs. A settle (settee) that Daddy had built for himself was squeezed into one corner. Mommy had made a feather cushion for it.

The bedroom at the back where Mommy and Daddy slept held a double-size bunk similar to a bin mounted on the wall about three feet off the floor. The space under the bed was used for storage. A feather mattress comprised of bleached flour sacks stuffed with feathers filled the bin. A long pillow also crammed with feathers spanned the width of the bed.

A ladder through a small hole in the ceiling led to the tiny half-loft where my sisters and I slept. It was only a crawl space. Colourful catalogue pages covered the rafters, and 12-inch-wide planks separated our feather mattresses. Like the mattress of our parents, ours were fashioned from bleached flour sacks packed with bird feathers. They had to be dragged up onto the loft and made up with flour-sack sheets and homemade quilts.

Above the stove, skimmed tree limbs were suspended with line to hang clothes on. Nails in the wall behind the stove were used to hang caps, cuffs, and socks for drying. Mukluks were placed beside the stove to dry out overnight. Mom’s iron pots were also hung on nails around the stove. They were so heavy I could barely lift them. The woodbox located behind the stove completed the room.

And so the winter days began. There was work for everyone, and no one was too young to help out. How well I remember the chores I had to do.

“C’mon, Jos, ya gotta help me wit de wood!” Sammy hollered.

“But, tis too cold!” I cried.

“Oh, Jos, yer some tissy maid,” he grumbled, giving me a smack. Freezing, I watched as Sammy’s saw went swish, swish through the wood. The ends of the wood fell to the ground. Often I held the tips to avoid having to pick them up. But Sammy, being only 12 or 13 at the time, hadn’t yet mastered his saw-cutting skills, and sometimes the saw would stick and I’d fly off into the snow.

After the wood was chopped, it had to be split. With the well-sharpened axe in hand, Sammy placed a junk (log) of wood on the chopping block, raised the axe high overhead, and slammed it onto the wood, splitting it wide open. Then he cut it in half again to make it small enough to fit into the stove, and we carried it into the house. I was cold and just wanted to go inside to play. To my mind, there was never enough time for play.

When supper was finished, there was no time for play, either. Exhausted, I was happy to climb the crudely constructed ladder and roll into my nicely made-up bed. I lay there studying the images in front of me, praying I wouldn’t pee in my bed during the night. Through the flickering of the oil lamp I reached up into the blackness and touched the rafters. My imagination went wild as the pictures turned into monsters stretching out to grab me. Once the lamps went out, I had nightmares of demons and ghosts in the absolute blackness.

“Mommy, tis too dark an I’m scared!” I cried.

“Yeh? Ya better be good, too, or de boogie man’ll get ya,” she replied to this foolishness.

Courtesy Them Days magazine and the artist Gerald W. Mitchell.

Sawing wood in the Labrador wilderness.

We got our drinking water from the nearby brook. Daddy chopped two holes through the ice covering the water. One spot was used as a well for drinking water, and farther downstream another hole was used for soaking the salted dog food.

To fetch water, Daddy lashed the barrel onto the komatik and headed for the steady. He chopped a hole through the ice, scooped bucket after bucket from the brook, and poured them into the barrel. The water was then transferred into the barrel on the porch, which froze over during the night and had to be chopped free each morning.

For firewood Daddy had to take a daylong trip to cut wood. To do that he had to get his ninny bag ready the night before. It usually contained his ever-present knife, chewing tobacco, shells for his gun, matches, a kettle, and a small pot.

In the morning, while Daddy ate his toast and sipped tea from his saucer, Mommy hustled about, stuffing food into his grub bag — fresh buns, tea, a little salt and sugar or molasses, and a piece of fatback pork. The grub bag then went into his ninny bag. If Daddy was going to cut wood, he would use the komatik box to put his things in. It was also used as a seat. He’d lash it tightly onto the komatik, along with his rackets (snowshoes), axe, and gun.

Courtesy Them Days magazine and the artist Gerald W. Mitchell.

Fetching water in Labrador.

If Daddy was going to haul the wood he’d already cut, he would tightly lash the horn junks (wooden cradles) to each end of the komatik. They were contructed from two large pieces of timber just long enough to span the width of the komatik, with a hole drilled in each end. A stick about three feet long stood up in them, providing a sturdy wooden cradle.

Eventually, the wood was cut, limbed out, and placed in a neat pile by the side of the wood path ready to be hauled out. After several days of cutting, the dogs were harnessed, the wood was piled into the komatik between the horn junks, and then it was transported home by dog team. Once the green wood arrived, it was placed in the vertical woodpile so it wouldn’t be buried in a snowstorm. Dry wood was stacked separately.

Courtesy Them Days magazine and the artist Gerald W. Mitchell.

Hauling home firewood in horn junks in Labrador.

At dusk until well after dark each day Daddy and Sammy had to feed the dogs, top up the water barrel, saw the firewood, and chop up two armloads of splits (dry wood cut into kindling), which were brought in and neatly stacked near the stove to dry out. In our house dry wood was like gold and was always kept away from the regular wood. Some of it was used to make wood shavings, and no one was allowed to touch it. The trick was not to let the fire get so low that we would have to use the dry wood.

To cut the wood shavings, Daddy used a drawknife, a tool ideally suited for the task. It had a large steel blade about a foot long, with wooden handles bent toward the sharp edge of the blade, designed to be pulled toward you. Daddy sat on the floor, facing the stove, and squeezed the kindling between his knees for stability. He then placed the drawknife three-quarters of the way up the wood. I always watched intensely as he pulled the drawknife toward himself, afraid he would cut right into his belly. But with great precision he never failed to stop an inch from his body. I can still hear the sound of the wood curls being separated from the junk as the sharp blade forced its way through the wood. Daddy cut into it with just enough pressure and speed to make a neatly curled shaving. He then put the next one behind the first, and so on, until there were several neat curls still attached to the wood. After that he started another junk until there was enough to start a fire. Daddy made it look so easy.

“I wanna do dat, Daddy,” I said. “Can I try?”

“No, Jimmy, ya can’t do dis. Tis too hard fer ya.”

“I can do it, Daddy,” I insisted, tugging at his arm. “Lemme try.”

“Awright den.”

Handing me the drawknife, he showed me where to place it on the wood. With great tenderness and patience he let me pull and struggle for a while. I couldn’t get the blade to move. “Tis stuck, Daddy!”

“I tol ya twas too hard fer ya,” he said. “Ya can try again when yer a little bigger.”

Every evening, after the dishes were cleared away, Mommy sat in her favourite chair with her sewing machine or knitting needles. Daddy, with all his outdoor work done and the shavings cut, lay back on his settle and had a little rest. If his day hunting in the woods was successful, we had roasted partridges for supper. After a short nap, he played a few songs on his accordion and Mommy danced around the room. We danced around the cabin, too, happy and secure with a belly full of food and a nice warm fire.

The husky dogs were our lifeline and had to be well cared for. Daddy made the dogs’ harnesses and traces and the bridle used to pull the komatik. The dogs’ harnesses were created from rope that had to be taken apart and braided back together to make it more pliable and softer around the animals’ bodies. The rope was then spliced at the end with a loop where the traces were attached. The traces were made of bank line, which was the size of a pencil and had a distinct tar smell. The bank line was tightly woven and quite rigid. The traces were then attached to a bridle, which was fashioned out of a larger rope braided together from three pieces of rope with a loop at one end for the traces. The other end was forked into two separate ropes, with each side attached to the first rung of the komatik.

Feeding the dogs was a daily chore for Daddy. He took the salted fish products down from the scaffold and soaked them in the brook for a day. Then he cooked food scraps and cornmeal in a big five-gallon bucket on the stove. Outside the dogs sniffed their food cooking and began howling and yelping. Once the cornmeal was cooked and poured into the feeding tub, Daddy added the frozen food to make a nourishing meal for the dogs. I enjoyed watching them crowd around the circular tub, gobbling their food in a feeding frenzy.

Courtesy Them Days magazine and the artist Gerald W. Mitchell.

Feeding sled dogs in Labrador.

By the time the dogs were fed, it was dark and suppertime. Mommy was busy cooking seal meat, rabbits, or some other game for supper. Daddy came in, washed his hands in the basin, and proceeded to his settle to wait for supper. After we ate, he cleaned his traps and guns.

“Whass ya doin now, Daddy?” I asked, leaning on his knee.

“Gettin ready ta set me traps, Jimmy,” he said, his gentle voice filtering through the tiny cabin.

“Where’s ya goin dis time?” I prodded, wanting to know his every move.

“Oh, jus in de woods lookin fer partridges, an I’ll set a few rabbit snares an a few traps.”

“Can I go?”

“No, Jimmy, yer too small yet. Maybe when ya gets a little bigger ya can go.”

I knew that would have to do, so I just sat and watched him. To clean the barrel of his gun, he took a long rod with a little piece of cloth like a bow attached to it. Once the barrel was cleaned, he poured gunpowder into it. It was a charcoal-grey substance and smelled strange. He then dropped in a wad, gently padded it down, and dropped in a piece of lead, then another wad. The gun was now ready, and he carefully stood it against the wall beside him.

“Dat’s not fer ya ta touch,” he warned.

“Why?”

“Cuz ya could blow yer head off, dat’s why.” Daddy never yelled at us. However, when he used a certain tone of voice, there was no questioning his authority.

In the dead of winter the temperature could dip to minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit. The frost got so thick on the windowpanes that it formed mounds of ice, making it impossible to see outside. When our mittens got wet, they stuck fast to the icicles. If we tried to pull our mittens free, they ripped.

“Don’t stick yer tongue on dem ol tings or ya’ll be sorry,” Mommy warned.

“Okay, Mom,” I piped up as I ran out the door to play. I admired the icicles hanging from the cabin. They glistened like glass as the brilliant sunshine shone through them. Holding a broken piece of icicle in my hand, I glanced at my sister. “What’ll happen I wonder?”

“Yer tongue’ll stick ta it,” she answered. “Dat’s what’ll happen, an ya’ll never git off.”

“Oh, yeh? Can I try?”

“No, Jos,” Marcie said. “Ya’ll be sorry.”

Always the defiant one, I touched the icicle with the tip of my tongue. It stuck. Solid! I couldn’t get it off at all. It hurt so much, and I was terrified of what my mother would do to me if she found out. I tried and tried, but my tongue wouldn’t come unstuck. I started to cry and now had no choice.

“Aw, Mommy, it hurts!” I cried, racing back inside the cabin.

“Good nough fer ya, ya bloody little fool. I tol ya not ta do it.”

“Aw, Mommy! Tis some sore an tis bleedin, too.”

“Serves ya right,” she said as she melted the huge icicle off my tongue. “Cuz ya won listen, will ya?”

Mommy didn’t remember a terrible incident that happened during the winter I turned seven. She might have been somewhere having a baby at the time. I’d peed in my bed again as I did every night. With my teeth chattering from the cold, I crawled across the floor, clambered down the ladder, and pushed aside the curtain Mommy used as a door to separate the bedroom from the kitchen. Daddy was putting wood in the stove.

“I’m cold, Daddy,” I murmured as I wrapped my arms around his legs.

“Awright, Jimmy, de stove’s getting hot now. Ya’ll be warm soon.” He put me on a wooden crate in front of the curtain to warm up. At that moment Marcie came out of the room, pushed the curtain aside, and accidentally shoved me onto the stove. I screamed. Daddy pulled me off so quickly that I didn’t burn too badly. I’m thankful that the stove wasn’t fully hot, but it was hot enough to give me nasty burns on both of my arms. I carry the scars to this day.

The long winter dragged on, and even though we were trapped inside the tiny cabin for weeks, we found ways to entertain ourselves. There was no electricity, radio, or television, no colouring book or crayons, no storybooks or board games. And there was no space for activities. So Daddy made us little toys — a spin top out of an empty cotton spool, a crossbow made from wood. When we found a piece of string, we played cat’s cradle and other simple games such as button-to-button or gossip. Cat’s cradle is simply a piece of string tied together. Using our fingers, we made different designs with it. Daddy also whittled little dolls from wood. We always managed to find something to do but certainly weren’t allowed to fight with one another. A crack on the head with Mommy’s knuckle taught us that early on.

Life in Roaches Brook was harsh and very primitive. The daily trip into the woods to cut enough firewood for both summer and winter was daunting. All the wood for Spotted Island had to be cut and hauled out to the landing point. Then we took it by boat to Spotted Island once the ice broke up in the spring.

Monday was washday, and with temperatures at minus 30 degrees, the clothes would freeze before Mommy even got them pinned on the line. Mommy had two bedwetters, so trying to keep Sammy’s and my beds clean of pee was a never-ending chore for her. She just couldn’t keep up. Consequently, night after night, I went to bed in my pee-soaked feather bed on the wooden floor of the loft. It was hard, cold, and wet.

The constant struggle for food was always foremost in my parents’ minds. Once food was provided and prepared, Mommy was busy sewing and re-sewing our clothing, fashioning mittens, socks, and caps, and darning everything we wore. Her tasks kept her working until she practically fell off her chair. They were such devoted parents and worked diligently to keep us alive.

We weren’t without fun, however. The few families in Roaches Brook whiled away the long winter nights by playing cards, making their own music, and dancing whenever they got the opportunity. And so the long winter passed.

Eventually, spring arrived and it was warm enough to snow. And snow it did! In spring we could go outdoors and play, and play we did! We climbed onto the mounds of snow and slid down on our small komatiks. We built houses of snow and snowmen and had snowball fights. It was so much fun! We’d go into the cabin with our clothes soaking wet, and Mommy would grumble at us for staying out too long. We were a happy family then.

“Yer gonna catch yer death,” Mommy would say, and we’d just grin.

Fierce spring storms buried our little cabin, plunging us into complete darkness. Daddy would have to dig us out. I didn’t know we were always on the brink of starvation. I didn’t know there was any other place in the world.

At night as I lay in my small bed in the half-loft, wishing I wouldn’t pee that night, I heard my parents talking softly to each other. In the flicker of the oil lamp I saw the pictures on the catalogue-covered rafters. They seemed to move, dance, and clutch at me. Daddy was probably nodding off downstairs and then they would bank the stove and retreat to their feather bed. Such was the life of a hunter and trapper.

Such was our life in Roaches Brook — place of my birth.