Читать книгу So Few on Earth - Josie Penny - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6 Hunting and Trapping

The Labrador fur trade started legally around the middle of October, but the actual beginning of the season was variable. It took time for the animals to grow their winter coats. Therefore trappers waited until later in the fall when thicker furs brought better prices. From year to year the success of the fur trade varied. The quantity of fur-bearing animals always ran in cycles. Some years were extremely good, while others were very poor, so there was constant concern for the survival of our people. Weather played a major part in the success of the season and the quality of the furs. The distance and frequency that the trapper was able to attend to his traps were always factors. So, too, was knowing the right place to set the traps.

The local custom was never to set foot on another trapper’s territory. Many trapping grounds were kept in the family for a century or more and were passed down from generation to generation. A trapping ground was never intentionally infringed upon by another trapper. The closest trading post was many miles away. The nearest one to Roaches Brook was Cartwright, which was 60 miles distant. The forest brought everything we needed to sustain us for the winter — wood for heat, animals for food, and fur to trade for clothing and essential items.

Leg-hold traps were the only type in existence at the time. The different sizes were geared to the size of the animal. The bigger traps were used for lynx, beaver, wolf, and fox, while little ones were for mink, martin, weasel, and squirrel. Aside from trapping for the fur trade, it was crucial to go hunting each fall for edible animals. Gaming licences and permits weren’t required in the 1940s and 1950s. There were no laws or law-enforcement officers to be seen. People were free to hunt at will.

Some hunting memories are very clear. I was skipping up the path toward our Spotted Island cabin one day when I heard Sammy yelling. “Der’s a walrus in de boat! De men gotta walrus! Boy, oh, boy, tis some big, too!”

“Whass a walrus, Marcie?” I asked.

“Dunno, maid,” she answered.

I ran as fast as my little legs could carry me down to the stage to see what the commotion was about. It was the biggest thing I’d ever seen!

“Whass dem big white tings stickin outta his mouth?” I asked, fascinated by two long curved white bones bigger than my body.

“Der tusks!” Sammy hollered.

I thought my big brother knew everything. I didn’t understand tusks, so I shut up and marvelled at the scene in front of me.

It took all the men in the community to haul the gigantic carcass up onto the beach. As always, when they were needed, every able-bodied man was there to help. The carcass was carved up, and the blubber was set aside for the dogs. The remaining meat was shared with the whole village. The walrus provided a lot of meat, and it left a big mess on the beach.

My memories of Roaches Brook are equally clear. I adored my father and followed him around whenever possible.

“Whass ya doin now, Daddy?” I asked as he limped around the porch and reached for a wooden box and a tin can high on a shelf.

“I’m cleanin me guns now, Jimmy. I’m goin huntin tomarra marnin.”

“Whass dat fer?” I asked, pointing at the tightly lidded can.

“Gunpowder. An tis not fer ya ta touch if ya wanna keep yer head on yer shoulders.”

“Why? What’ll happen ta me head?”

“Never min why, Jimmy. Jus don’t ever touch it.”

A hunting trip was a major undertaking, especially if the men went inland for several days to search for bear and caribou. Those trips were usually made in the winter or early spring around March and April and involved several hunters. Each hunter borrowed extra dogs from other men in the community to be sure they could transport their game back.

Hunting for small game such as partridge, porcupine, and rabbit was almost a daily event. In the fall it was mainly seabirds and seals that the hunters brought home. Daddy would return with lots of birds. Turrs (murres), geese, and ducks were the most plentiful.

The next job was to pick (pluck) and clean them. Mommy had her work cut out for her again. To pluck dozens of birds she had to get the stove hot. Once the stove was hot enough, she hauled her sleeves up, straightened her pinny, slicked back her hair, and got to work. With her left hand she held the wings and neck while her right hand kept a firm grip on the feet and tail feathers. This grip exposed the full breast area. I watched as she dipped the bird into a large pan of water and then rubbed it across the hot stove in a fast, vigorous motion. Water bubbles danced across the stove. The steam penetrated the feathers and scalded the skin of the bird, which allowed the feathers to be plucked more easily. Mommy was fast and could pick a bird in a few minutes.

The smell of scalding skin and scorching feathers was nauseating. “Pooh, dat stinks, Mommy,” I grumbled.

“Yeh, Josie, it do stink. But dey’ll taste good on yer supper plate, won dey?”

“Oh, yeh, Mommy. Can hardly wait.”

In late October winter set in quickly. The damp frost that started in late August was thick on the ground and clung to everything. By December it became extremely cold, but the air was very still and bright with sunshine. On a calm, frosty morning the air was so still that smoke from the stovepipes floated skyward straight as an arrow. On a clear, frosty night the stars, the northern lights, and the full moon shone so brilliantly that newly fallen snow sparkled like diamonds. Glittering light blanketed my world, making it as light as day.

After Daddy secured enough wood and water for a few days, he settled down to prepare his traps. He lifted the huge bundle off the nail in the porch, which looked to me like a snarl of rusted metal. The jingling and banging stirred my curiosity.

“Whass ya doin now, Daddy?”

“Cleanin me traps, Jimmy.”

“Why?”

“So dey’ll work right.”

He opened a huge bear trap, cocked it, then tripped it shut with a loud bang. It terrified me.

“Oh, Daddy! Better not put me fingers in der, hey?”

“Not less ya wants ta lose em,” he said calmly.

When he finished cleaning all his traps, he was ready. “Everything’s ready ta go,” he said with a satisfied look on his face. He then retired to his settle for the evening.

“Can ya play us a song, Daddy?” I asked, tugging on his pant leg.

He picked up his accordion and began playing a tune. I danced happily around the floor.

“Time ta go ta bed now, maids,” Mommy piped up after a time.

Oh, why did she have to spoil everything? I thought. But I knew there was no arguing with her. I climbed the ladder to the half-loft and crawled into my feather bed. As I snuggled under the weight of Mommy’s homemade quilts, I felt sad. I didn’t want Daddy to go away. I listened to him play for a while and then everything became quiet and very, very dark. It was too dark to see the printed catalogue paper that covered the rafters just above my head.

The next morning it was still dark when I awoke to the delicious smell of freshly steeped tea and homemade toast. I heard the crackling of the splits as they quickly burned away, and felt warmth filtering into my loft. Daddy had already lit the fire, boiled the kettle, and made his breakfast of tea and toast. My parents were talking softly.

I felt so scared about my daddy going away. The smell of toast made me hungry, so I crawled down the ladder and stood on the orange crate beside the stove. I watched Mommy bustle about, getting everything ready for Daddy. I wanted to see him off. Mommy had made pork buns for him, his favourite.

Daddy took his ninny bag from the nail beside the stove and laid it on the table. Into his bag he put a tiny homemade stove, a blackened kettle, a small cooking pot, some snare wire, a small ball of line, ammunition, fish hooks, and a skinning knife. Into an old shaving kit bag he placed his chewing tobacco and matches. Before he left he used a whetstone to sharpen his axe and all his knives.

“Whass ya doin now, Daddy?” I asked as he spit on the stone to wet it.

“I’m sharpnin me knife, Jimmy,” he said, swirling the blade around and around in a circular motion and making a soft, grinding sound.

“Wha fer?”

“So it’ll cut better.”

My father worked efficiently and effortlessly, almost as if in slow motion, very focused and methodical. He picked up his axe and braced it between his knees to check the sharpness of the blade. Then he pinned the handle on his thigh with his elbow, held the heel of the axe in his left hand for stability, took his sharpening stone, and pushed it across the blade. He started from the inside corner and pushed outward, making that soft, grinding noise. Spit and grind, spit and grind. I could see the tip of the steel blade start to gleam.

“Looks sharp now, Daddy,” I said, my face close to the blade, studying it.

“Yeh, Jimmy, tis,” he said, wiping it clean and leaning it against the wall. “Don’t touch it,” he added, looking at me with a warning grin.

Daddy then double-checked his supplies. He was ready. With quiet anticipation he hung his ninny bag and his traps on his gun barrel, slung the gun over his shoulder, and set out. Swoosh, swoosh went his rackets, rubbing together as he limped through the snow. I could hear the traps jingling, and a tear trickled down my cheek as I watched him disappear into the woods.

Everything became silent as we wondered if he would be safe. He might travel several miles in a day, setting his traps as he went. It was a time-consuming job, and finding the right place to set each trap was critical.

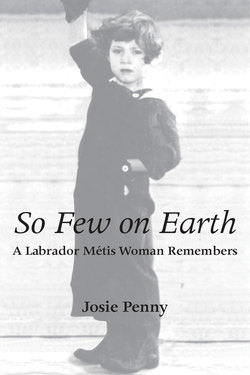

Courtesy Them Days magazine and the artist Gerald W. Mitchell.

Loading up a komatik for a trapping trip in Labrador.

For fox and mink a trapper would usually set traps along the shoreline under a large tree or in the mouth of a burrow. Mink traps could be set in a river in air pockets where the animals travelled in and out for food. A trapper had to know the habits of the animal. The better he was at predicting the animal’s behaviour the better chance he had of trapping it. Lynx preferred heavily wooded areas. Mink and weasels were the easiest to trap. Weasels were plentiful, and since they weren’t suspicious, the trapper didn’t have to conceal the traps, which was a difficult process. However, traps for fox and lynx had to be hidden because they were such crafty animals. For fox and lynx a trapper had to be sure to leave as few clues as possible. After the traps were set on the initial run of the line, the trapper had to wait overnight and hope he would get something. Exhausted and weary, he would put up his little canvas tent, cover the floor with boughs, and set up his tiny stove. All these items he carried with him. There were no sleeping bags then and none of the warm synthetic clothing we have today. In order not to freeze to death the trapper had to keep the stove going all night.

First thing in the morning the trapper made the rounds, checking each trap, emptying and resetting them as he went. The animals were frozen solid and remained that way until he got them home.

Daddy hung the frozen animals near the stove to thaw out before they were skinned. The few animals not yet frozen were skinned right away. The skin was turned inside out and pulled and stretched over special boards carved in the shape of the animal. Little nails tacked the skins to the end of the board to keep them from shrinking while drying. They were then placed high on the cabin beams to dry. Once thoroughly dried, they were turned right side out and kneaded until they were soft and supple. The pelts had to be cleaned thoroughly. Not doing so would leave an odour and reduce the quality of the fur. Traders wanted only clean, odourless, well-cured pelts.

Getting to the trading post was another feat because the closest one was a two-day trip to Cartwright, 60 miles away. Winter storms were brutal and could come without warning. During a major storm or a cold spell, we were trapped for days inside the cabin. With the temperatures at minus 50 degrees and winds up to 100 miles per hour, nothing moved. A mound of snow was all we could see of the dogs as they were completely buried.

The silence was deafening after a storm. It was dark, but not like the darkness of night. This was different, like a grey hue everywhere. Many times I heard Daddy get up from his quilts, limp to the window, blow a peephole through the frost to check the weather, and see nothing but a wall of snow.

“Der’ll be no wood cuttin or huntin taday, Mammy,” he’d say with a sigh.

“Is we buried again, Tom?” she’d ask Daddy from her bed in the darkness.

“Yeh, Mammy, and tis too starmy ta go anywhere.”

“My, oh, my, whass we gonna do I wonder? We got nuttin fer de youngsters ta eat.”

“We needs ta get sometin soon or we’ll starve,” Daddy would answer, concern evident in his voice. The possibility of starvation was very real.

To go hunting for big game involved several men in the settlement as a group, and they could be gone for a week or more. Daddy used all his dogs to hunt big game, and any spare dogs he could borrow, especially if they went inland for caribou.

The hourglass was the only way to monitor the weather. So if it looked favourable for several days, the men geared up. To prepare for such a trip, Daddy cleaned his guns and loaded them and checked his harnesses and any other supplies he might need. Mommy packed his grub bag with flour, molasses, salt, fatback pork, and tea. She made sure he had a change of clothes in case he got wet.

Daddy was up well before dawn to harness his dogs in the darkness. They ran around in a frenzy, anxious to get going. Daddy had to place a heavy chain under the runners as a brake to hold them back. Hunters loaded the komatik boxes and lashed them down. They took snowshoes, axes, guns, ammunition, food, extra clothing, and stoves. They had to be well prepared. Survival depended on it.

The dogs were pulling, trying to get going, as Daddy loaded the komatik. When everything was lashed down, Daddy lifted the chain and off they went, racing at full gallop into the forest on the well-beaten path.

“Bye, Daddy!” I hollered as the komatik raced effortlessly over the newly fallen snow.

“Be careful!” Mommy yelled.

With a wave of his hand he was gone.

We were left alone again. I have often wondered how we survived, how Mommy kept us alive in the total isolation of the wilderness. I have often wondered how she felt. Was she terrified that Daddy would get hurt and never return? There were so many things that could have happened to him all alone in the forest. A trap could accidentally snap shut, he could cut himself with the axe, he could fall through the ice, and he could get knocked of his komatik and freeze to death.

When Daddy was gone for several days, it was essential that Mommy go hunting, as well. She was very capable of keeping us alive under extremely adverse conditions.

“Weers ya goin, Mommy?” I asked as she hauled on her pants, dickey, and sealskin boots.

“Jus goin in de woods ta try ta fin sometin ta eat,” she answered as she slung her rackets and .22 over her shoulder. She was accurate with that gun and seldom missed. We all knew we would have partridge, rabbit, or porcupine stew for supper that night.

By this time Sammy was 11 years old (five years older than I), and old enough to set a few rabbit snares close to the cabin. He checked them each morning and often brought a few rabbits home.

When Daddy returned from a hunting trip, we watched anxiously as the team approached the cabin to see if he brought fresh game. We were hungry! The dogs started yelping as they approached the settlement as if to say, “We’re back! Get the food ready!” They were always happy to get going but just as delighted to return home. When Daddy came to a stop, they rolled gleefully in the snow, grooming and licking their fur, content that they’d gotten their master home safely.

The caribou carcass was unloaded and placed on a scaffold out of reach of wild animals and dogs. The small game was stored in the porch where it stayed frozen. This time the hunters had had a successful trip, and it was a joyous occasion for all of us. The meat was shared among everyone in the settlement.

On stormy days when my father couldn’t go into the woods to cut wood or check his trapline, he worked on his furs or made a pair of rackets, new harnesses for his dogs, a new bridle, or a whip. Sometimes he knitted a fishnet for the summer fishing season or even built a new komatik. One day he brought two long pieces of wood into the cabin.

“Whass dey fer, Daddy?” I asked as he laid them along benches he’d placed at each end of our tiny cabin.

“Gonna make a komatik now, Jimmy, an ya better stay outta de way,” he warned. With his hand drill he punched out a line of holes down the edges of each plank. He was very careful not to break his drill bit.

“Whass all de holes fer?” I asked.

“Jus watch an ya’ll see.”

I sat and watched my father work for hours on end. It was a big undertaking to build a komatik. For the sides he used two straight pieces of timber about eight to 10 feet long. Several days earlier some neighbours had helped him rip (cut) the planks on the huge pit saw set up in the centre of the settlement. The first thing he did was plane the wood. Once the planks were planed out and smooth, he attached a curved nose piece to them. Then he had to saw and cut all the wooden bars, the end of each piece carved similar to the cap on a bottle. He drilled two holes in the ends of each board. He didn’t use nails. Nails were hard to come by and they cost money, which we didn’t have.

To assemble the komatik he lined the boards up along the sides and threaded babbish (sealskin strips) through the two holes in the board and down through the holes in the sides of the komatik until all the bars were snugly in place. As the babbish dried, it shrank a little, making the construction quite sturdy. Once all the bars were strapped firmly to the sides, Daddy turned the komatik over to attach the steel runners along the edge of the wooden sides.

“Whass dat?” I asked as he placed a runner along the side and drilled the holes to attach it.

“Runners. Makes her slide better in de snow.” Daddy glanced at my big brother. “Tis awmost done now. Can ya help me turn it over, Sammy?”

When they turned it right side up, it looked huge.

“Tis some big, hey, Daddy? Looks beautiful, too. Will ya take me randying [sledding] now?”

“No, Jimmy, not now,” he answered a little sharply. He was tired, so I sat quietly, thinking in my little six-year-old mind of the wondrous thing he had just accomplished.

In the darkness each day when Daddy arrived home, he unharnessed the dogs and fed them. Then he unsnarled the harnesses and gear, hung everything on the nails on the porch, cleaned out his komatik box, sawed the wood, brought it inside, and fetched water from the brook. When all that was done, Daddy was finally able to come inside, wash up at the basin, and sit down at the table for supper.

After supper he skinned the animals he’d trapped that day and cleaned the fur. Mommy placed his clothing around the stove to dry, turning his sealskin boots inside out. All the work was done systematically and in order of importance. Nothing could be left undone.

Hunting and trapping were very hard jobs. And even though Daddy was partially handicapped from polio, he still had his work to do. He had only shrivelled flesh on one leg. When he walked, his foot flung outward as if there was a spring in his knee joint. In spite of his condition there was no such thing as being too tired or too cold or too hungry.

To stay alive every task was important and had to be done.