Читать книгу Seven Sisters and a Brother - Joyce Frisby Baynes - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDay One

Locked Inside

Members of the Afro-American Students Society took over the admissions office of Swarthmore College today and vowed to remain until they [were] given a voice in policy-making and more Negroes were admitted. About 40 students filed quietly into Parrish Hall, began locking doors and refused admittance to anyone.…”The police were not called in and I hope we never have to call them,” said the College vice president…[he] said he hoped the dispute would be “solved amicably.” Swarthmore has an enrollment of 1,024 students, 47 of them Negro.7

On a cold but gloriously sunny day in January 1969, a small cadre of black students took control of the Swarthmore College Admissions Office. We entered at lunchtime when most employees were on their breaks. While Harold began securing the doors, Aundrea and Marilyn A. approached each person still at their desks and asked them individually to leave. They had both practiced what they would say and how.

No one will get hurt. Please take your personal belongings. We are taking control of the office and it may be a while before you’re able to return.

They were all white women who were much older than we were, and they grabbed their coats and purses and scrambled out of our way into the hallway, leaving their paperwork behind. They had no idea that it would be more than a week before they would see their desks again. Neither did we.

A more non-threatening group of college students would have been hard to find. We were all in reasonably good academic standing at, arguably, the best small college in the nation. We had to prepare for fall semester final exams. We carried our books along with us, so we could keep up with writing final papers and test preparation in case the sit-in took a day or two longer than the one or two days we had anticipated.

Other SASS members waited at the back entrance for the signal to come in. Once all the office employees had left and Harold had secured the front door, Aundrea and Marilyn A. hurriedly unlocked the chained rear door and let in the rest. A flurry of activity followed as each one took in the premises and began settling in.

What needs to be done?

Help Harold tape the black paper to the windows and push the wedges under the door.

Organize the survival kit stuff and put it in one spot. We need to know how much we have so we can figure out how to make it last. How many cans of sardines did we list on that planning sheet?

Aundrea and Jannette will be in charge of food distribution to make sure we don’t run out. We know how to make food stretch.

Put the first aid stuff here, flashlights and batteries.

I brought my record player and Nina Simone, James Brown, Aretha, gospel music. Anyone else brought records? Put them over there.

Harold, do you have that guard duty schedule ready?

Yes, everyone has to take a turn at guard duty, all day and all night.

Two hours at a time. At the doors or at the window ledge.

The New York Times in 1969 was wrong in its estimate. It would actually be several days before the number of student protesters would reach forty. A 2019 New York Times profile of Ruth W., one of the freshmen occupiers, cited her fifty-year-old memory as counting twelve occupants. Perhaps twelve entered in the first hour, shortly after those who first secured the premises let them in. Before that first night ended, there were at least twice that many members of SASS who had brought sleeping bags, books, and enough snacks and personal essentials that would allow them to be away from their dorm rooms for a day or two. Other freshmen besides Ruth came inside on day one, despite some worrying about what their parents would say when they found out.

Setting the record straight may take decades. The official campus newspaper, the Phoenix, also got it wrong in many ways. Its coverage of the start of the admissions office occupation identified almost none of the students who led the action and invented an implausible narrative of the chain of events that claimed the spokespersons negotiated with the College dean to access the premises.

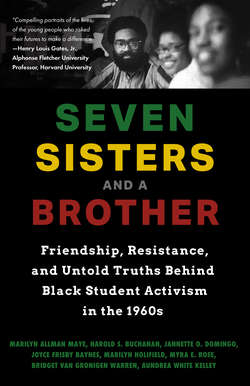

What we would later call the “Takeover,” but what the College administration dubbed the “Crisis” had just begun. While it was carried out under the auspices of SASS, in actuality the protest was the brainchild of a group of students known as the Seven Sisters, plus one Brother.

None of the media’s photographs or articles recognized that it was women who had organized and led the Takeover. No press accounts named or showed a woman. We had intentionally asked some brothers to be the media spokespersons. It’s likely the reporters never asked them who planned the Takeover, where or when.

Since its founding, Swarthmore College has had a mission of not just educating students academically, but of educating them to make a difference in the world. Swarthmoreans call it their “Quaker values.” It has historically been students of the College who have spoken out and protested about the apparent discrepancies between Quaker values and the College’s investments in things that don’t improve the planet, such as apartheid and fossil fuel. We were a part of that tradition when we peacefully took over the College Admissions Office in 1969. Little did we know that forty years later, the College administration would call our action the single most consequential event in its 150-year history. What they called the “Crisis” was the cataclysmic event that forced college administrators to wake up and respond to our demands for respect. Respect for black people. Respect for black history. Respect for black culture. Black students refused to be invisible.

The College would be put to a test of its values like never before. It had failed more than once in earlier tests.