Читать книгу Seven Sisters and a Brother - Joyce Frisby Baynes - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFlood Gates of Memory

After my father died in 2008, I was going through his things and found a letter that I had written to our family. Although the year was 1969, the letter is incorrectly dated January 31, 1968 and starts out:

January 31, 1968

Dear Everybody,

I finished my last exam yesterday so now I finally have time to write to you. I know you were all concerned over my actions and their possible consequences in the past month, so I am writing this letter to try to explain.

When I first entered Swarthmore College, I did not know what to expect. True, I had gone to a white high school before coming here but somehow I expected it to be different. For about two months my roommate and I went everywhere together, the whole bit strictly “integrated.” I saw other black people on the campus but did not associate with them. Although [she] and I did have a few things in common I never really felt comfortable and felt very lonely. Then I met Bridget, Aundrea, Janette and other black girls who were freshmen. Being with them was just like being at home and things began to look up. Also, during this semester SASS (Swarthmore Afro-American Students Society) was formed. I believe I wrote you all about that. Since that time (Fall 1966) SASS has been trying to effect changes on campus for black students. Nothing really radical like a black dorm or things like that, just simple things like course(s) in Afro-American history, literature, philosophy, etc., that would benefit the whole school. When we bring speakers to the campus, white students come in droves, they even outnumber us. SASS also asked that they be consulted about anything on campus that affected black people. The school did not do this. Last year they had a South African (white) speaker that everyone was supposed to hear. Black students staged a peaceful walkout on the speaker at that time and still the school refused to listen to our requests and continued to walk over us. We were called “militants” and given all kinds of labels—even in the national news because we refused to listen to that man.

This year things really came to a head.… The Admissions Policy Committee, headed by Dean Hargadon, issued a report on black admissions…did not consult any black students when writing the report…and proceeded to write a very subtle racist document. What I mean is he used confidential information about our family backgrounds, incomes, etc., which really served no purpose and put them in the report (we could all identify each other).… Needless to say, all the black students on campus were very upset. An expert in black admissions, a woman from NSSFNS (a Negro scholarship group that helps black students get into white Ivy League colleges) offered to come down from New York to talk to the committee about the problem—they refused to see her. Their behavior indicates that they do not respect us enough to consult us on basic issues that concern us. They were ignoring our requests. Finally, we issued a set of demands in November about our grievances. The Student Council even endorsed our demands. The Dean of Admissions wrote them a scathing note saying in effect that he was sorry that he had let them into Swarthmore. President Smith asked for a further clarification of our demands… just one of their techniques to stall us. The final re-clarification was made just before Christmas and presented to the administration as non-negotiable demands. We still were given no answer. Two days after the deadline we held a meeting with the whole school to further express our grievances. The next day an effigy of the school was burned. The next day we occupied the admissions office…

Our occupation did what it was planned to do. We had finally shocked them into some action. Faculty meetings were held every day—an unprecedented fact. Administration efforts to alienate white students from us failed. Most students were in agreement with our demands. Others saw that the success or failure of our efforts had definite implications for student power. People from the black community helped tremendously and brought food and anything else we needed especially the moral support. …[Through] the news media we have been called everything from extremist black militants and murderers (as if we had control over Smith’s heart) to being a part of a Communist conspiracy. They will do whatever they can to discredit you and make you seem like an extremist when in reality SASS is one of the more conservative black student groups. I am enclosing a copy of the Phoenix, the school newspaper. It has the most accurate coverage of what really happened.

At any rate, we have not given up our objectives and we continue to press for them. The faculty is meeting at least twice a week now to bring about a settlement of the issues. I will tell you if anything new develops.

Our scholarships are not in jeopardy. The administration would look bad in the students’ eyes if it did something like that.

My arm is getting tired of writing, so I guess I will stop…

Keep the faith babies!!!

Myra

After reading the letter, I realized that now it’s an artifact, a hand-written record of what happened and why we did what we did. I read and re-read the letter and immediately telephoned Marilyn A. “You’ll never believe what I found,” I told her. That letter opened the flood gates of memory.

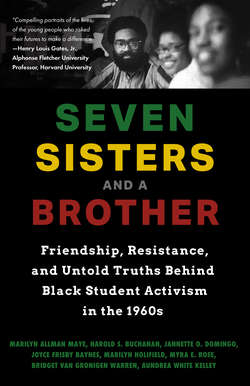

We were known as the Seven Sisters back then, but were actually the “Seven Sisters + Harold.” My experiences with this band of believers at Swarthmore pointed the way for me professionally as I learned to always seek the truth, stand for what is right, and model collective leadership long before I had heard of the concept.

Growing Up

I had a happy childhood and was the oldest of four children raised by Joseph and Ednae Rose. I was “the different one.” I was the brown one, the fat one, the ugly one who did not look anything like either my father or my mother. We lived in Liberty Park in Norfolk, Virginia, a Depression-era, pre-war housing project of pasteboard homes. The houses were connected with ribbons of asphalt on tar-based streets that wound through what had once been a large wooded area complete with ditches, winding streams, and lots of trees. We even had our own elementary school and city-run recreation center. The only black hospital in town, Norfolk General, was next to both the edge of the projects and one of the in-town enclaves of the black middle-class.

I never knew my maternal grandparents as they had died long before I was born. My mother and her four sisters were left to raise each other beginning in their late teen years. Ednae is my stepmother, the only mother I have ever known. She was short, light-skinned with full lips, a big nose, no hips, and short nappy hair that she did not like, but she was the prettiest woman I have ever known. She was a great dresser and the very definition of “style,” although she made almost all her clothes. She was never seen without makeup until her later years. I did not know that she had full dentures until I was a teenager. The fact that she was my stepmother only bothered me in that I did not look like her and did not have her style, her beauty, or her way of existing in the world. Ednae was an outgoing, gregarious person who “never met a stranger.” When she was in college, she was voted Miss Morgan State. Her confidence was awe-inspiring, and if she had any major insecurities other than some of her physical attributes, she hid them well. When her hair did not please her, she colored it or wore a wig. She was a master at makeup and had some foam rubber inserts that fit into the girdle that all women wore those days to give her hips. She was something else and my father loved her.

My father was a plasterer who learned the trade from his father. He did the best housing construction and decorative circle ceilings. He owned his own construction company. He was a true Renaissance man, born in the country, who later migrated to the city with his family. He graduated from college with a degree in animal husbandry, was a member of the Navy shore patrol during World War II, and organized and played with the Brown Bombers, one of the pre-integration black football teams. Daddy always took care of his birth family. He spent a lot of time helping my grandmother, who in my early childhood years lived with two of her daughters and my three cousins in a four-room house. We saw Grandma nearly every Sunday at Sunday School, church, and sometimes after church. She was a mother of the church, a deaconess, and quite formidable. Daddy was always respectful to his mother whom I later learned was largely responsible for my being raised by my father.

My real mother was named Marian and died in childbirth at the age of thirty. Her family lived across the water in Hampton. I never knew how my biological parents met, but I understand that she was a schoolteacher. They had been married for a few years before I was born. I look just like her, as people who knew her said—like she had spit me out. My parents’ wedding photo looks like my father could have been marrying me with an old-fashioned hairstyle. For most of my life, I believed that my mother died in the throes of childbirth without ever getting to see me. I later learned that I was born via C-section and that my mother died of complications a day or so later. So, she probably got to hold me and name me. My father gave me this information when I was middle-aged. I cannot tell you how it comforted me to know that I was not a truly motherless child.

Apparently, her death was a big surprise to the doctor and my father who was called in the middle of the night and told that his wife had died. He walked around in a daze for several days and forgot that I was in the hospital. There were plenty of people who were willing to take me and raise me as their own. Apparently, I was quite the prize because I was an exceedingly adorable baby. Daddy was so distraught that he was really considering these options when Grandma told him to bring the baby to her. I lived in my grandmother’s house for the first few years of my life. Grandma wanted to keep me, but when Daddy remarried, Ednae stated that I was to come home with them. I think that this was the only family battle my grandmother ever lost.

So, I had a happy childhood: loving parents, one sister, and two brothers. I was the oldest, but definitely not the leader of the pack. That title will always belong to my sister Joanne, who to this day is the boss of us. I was the smart one, the quiet one who stayed in the background, the one who read all the time. I felt invisible in this family of extroverts who were physically beautiful and gifted in their own right. My brothers were excellent football players: Allen, the high school quarterback in a predominantly white high school, and Don, who excelled in college and went on to a short career in the pros.

The world we grew up in was Southern, segregated, and insular. We lived in public housing until I was fifteen. School, church, buses, the eating establishments that we could frequent, and our hospital were all black. The mailman, the bus driver, the teachers, local shop keepers, the staff at movie theaters , amusement parks, beaches—everything and everyone was all black except the white department stores downtown and of course everything on television. We were aware of the white world, which we had to interact with from time to time. This was always anxiety-provoking because you knew that they had the best of the best (they showed that on TV) and ultimately all the power over you. Nonetheless, we were happy. My father had his own business and was able to support his family. We grew up safe and protected in the projects. We had a car, a sandbox and picnic table in the back yard, a three-foot-deep plastic swimming pool, a green Plymouth convertible, a pickup truck, a console radio and record player, and a television when they became available.

This was a time when people who were black middle-class lived side by side with others who were on welfare. Our family was part of the black bootstrap generation that pulled itself up by its own efforts. Both of my parents were college graduates and higher education was always stressed and assumed. As the “smart one,” I always knew that I would go to college and that I would need a scholarship. I excelled in my segregated public school and was offered advanced placement to skip a couple of grades. My family wisely declined as other intellectual prodigies in the community did not fare well, developing “nervous breakdowns” and never quite living up to their early promise. I spent a lot of time in the library in elementary school to keep from being bored. I participated in local and statewide sponsored enrichment programs from junior high school onwards.

In addition to running his business, organizing/participating in early black football, and serving as a deacon in our church, my father was a prolific writer, philosophizer, and wannabe politician. He was concerned about the plight of the Negro (as we were called in those days) and was active in the community. He wrote and published a book in which he proclaimed that the solution to the race problem would be solved with miscegenation. He sent free copies to anyone that he thought might have some power or concern over the situation including every POTUS and major politician he could access. He wrote letters to the editor of the local white paper, wrote opinion articles for the Journal and Guide (the local black newspaper), and had a talk show on local black radio called “Joe Rose—Tell It Like It Is.” We had lots of lively conversations from which I learned to think critically and seek to understand issues at their most fundamental levels. He encouraged me academically and helped me get a couple of writing assignments from the editors of the Journal and Guide. Some of my fondest memories are of sitting around the kitchen table reading and reviewing his writings while I was in high school as well as on breaks from college.

My mother encouraged all of her children to excel in school and participate in social and extracurricular school activities. She encouraged me to sing in the church choir, sing in a local operetta (which I did), and join black middle-class social clubs like Jack and Jill (I did not). I was never a social butterfly and declined most of these activities, though I did become a debutante during my last years of high school. My mother made time to pursue postgraduate educational opportunities in oceanography and eventually returned to teaching in the only black high school in town. She was an excellent biology teacher and was one of the first black teachers to integrate the white high school in my hometown.

The integration of the public school system was a major event in Norfolk; white schools closed down for a year or two rather than submit to desegregation. After fifteen years in my insular black world, my parents decided to move out of the projects to a more suburban setting. White flight was out of control and previously unavailable housing areas were open to black families. My father moved us when I was preparing to go to Booker T. Washington High School. I was upset to learn that instead of going to that Mecca of black teenage life, I would have to go to the local white high school. Talk about culture shock. Up until then, I had limited contact with white people, but would now be surrounded by them. There were only ten black students in the tenth grade class, only two of us were in AP classes, and I had only one class that had another black face. Even though I was never a social butterfly, I did miss being a part of the black world.

I was largely ignored in high school. I learned to adjust to a different style of teaching and learning. I had taken two years of French in junior high school, but imagine my surprise when my high school French teacher only spoke French to the class and gave homework and all instruction in French. I failed the first “dictée” largely because I did not know what was happening, but I eventually caught on. Most of my other classes were uneventful, and I did well in high school without any validation or encouragement from most of the teachers. By the time I started looking at colleges, I had decided to apply to schools away from home.

Applying to Swarthmore was pure serendipity. I was sitting in the guidance counselor’s office—she thought I should go to trade school—when I saw the College catalogue, picked it up, and thought it looked nice, so I decided to apply. I had never heard of the school, nor had my parents. As far as I knew, no one in Norfolk had heard of the school. I applied to seven or eight schools and was accepted to each one. The final decision rested on the scholarship money that was offered. Swarthmore offered full tuition and two hundred dollars for books, so they got me sight unseen.

The Road to Swarthmore

Going to Swarthmore was to be the big adventure of my life. I always knew I would go to college, but never anticipated the path I would take. I always thought I would go to one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) like Howard University or Hampton Institute, which was right across the water from Norfolk and was essentially a local college. I knew that I could meet academic expectations anywhere with no problem, but I was never socially adept and basically felt like an outsider wherever I was. I was not looking for a husband or the usual social life that was an integral part of the HBCU experience.

Leaving home was harder than I expected. My brothers were too young to fully understand what was happening, but my mother and my sister did. We all cried and hugged each other several times that morning. My last image of the day I left is of my mother and sister standing outside on the walkway to the driveway, past the white wooden rail fence that my father loved and my mother hated. That is when I first really felt the loss of my family and all the love and security that they represented. I experienced a strange combination of sadness and anticipation.

My daddy and my uncle brought me to Swarthmore. They packed up my uncle’s big green Cadillac for the road trip. We left early in the morning and drove until we reached the Pennsylvania countryside. I had never been that far from home. The campus was beautiful with rolling hills and lots of trees. We arrived sometime late in the day. My daddy and uncle unloaded all my stuff in my room on the third floor of Willets Hall. Swarthmore had previously sent me my room location and the name of my roommate. Susan was already there and had placed her stuff on the left side of the room, so I took the right side. My daddy and uncle kissed me goodbye and headed back home. Then I was really alone.

All first-year women were required to meet with Dean Barbara Lange in the Quaker meetinghouse for some type of orientation. I had never been in a meetinghouse. It was spare, cold, undecorated, and not at all like any of the Baptist churches I had visited over the years. If there was a cross there, I did not see it. The wooden benches were hard and uninviting.

Dean Lange was a middle-aged white lady with white hair, a blue suit, and pearls. I felt like I had been transported to June Cleaver, no, Donna Reed land. Dean Lange embodied the spirit of those true representatives of the white women of middle America, portrayed on late 1950s’ black and white television, and I felt like I was in a foreign land where I barely understood the language. House dorm rules for freshmen were discussed. She talked about how fortunate we were to matriculate at Swarthmore. That Swarthmore was equivalent to Ivy League schools like Harvard, Yale, and the Seven Sisters women’s colleges, but with a smaller, more select student body. That was the first time I realized what kind of reputation the school enjoyed. When I looked in the Cygnet, the freshman handbook, complete with pictures and school of origin, most of the students were from the Northeast and had gone to Country Day Schools and prep schools. I had graduated from the public school system and attended segregated schools until the tenth grade. At that point, I felt like Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz and knew that I was not in Kansas anymore. I was disoriented and apprehensive. It became clear just how fortuitous it was that I applied and was accepted to Swarthmore College, unless you believe in destiny, and of course, I do. Dean Lange’s cold, ruling-class demeanor and her declaration that Swarthmore’s academic rigor was comparable to Harvard’s had scared the bejesus out of me for sure. The pressure to succeed became real to me.

I bonded with my roommate, Susan, who was from Ohio. We were both science majors and had many of the same introductory science classes. She was going to medical school, and I was going to teach high school chemistry. Susan was the person who would eventually introduce me to my best friend, Bridget, the first black person I spoke to at the College. Bridget was also studying to be a doctor and was taking the prerequisite science and math courses. For a while, the three of us associated mostly with each other as Bridget also lived in the same dorm. First semester of freshman year was intense for everyone as we were all trying to prove that we belonged there, could do the work, and most importantly for me, that I could keep my scholarship.

College Life Before SASS

My science classes began at 8 a.m. and afternoon labs were always required. My roommate and I went to dinner and attended several social and musical activities together. I was focused on doing well in class and tried to fit into college life as seamlessly as possible. The early part of the first semester was filled with learning my way around campus and meeting all academic requirements.

I was seventeen years old and I loved being alive. Magill Walk perfectly captured the majestic campus scene lined with oak trees and steps cascading down to the train station and the tiny commercial strip called the Ville. I have lots of memories of climbing the hill beside Willets Hall to get to campus for science classes. I have always loved the early morning sun, fall season on campus with leaves beginning to fall and blow around everywhere, me carrying the green drawstring bag full of heavy science books, dragging the bag up the hill behind me.

My green Swarthmore book bag was square camouflage green with a drawstring. It was waterproof and could hold all my textbooks along with several spiral notebooks and other school supplies. I remember thinking that you could always tell the science majors from the social science majors—the science majors all had a hump in our backs. It was sometimes necessary to change shoulders or drag the bag along because it was so heavy. Remembering that green book bag makes me feel that I have always been prepared to carry the load, whatever it might be.

Susan played the cello, which I had only seen occasionally on TV. I loved music, all kinds of music, and tried to be open to whatever music was around: organ music at Collection, bagpipes, hootenanny, even white rock and roll, but the string quartet concerts were my undoing. Susan loved the string quartet classical music concerts that were given in Bond Hall. At first, I thought these gatherings were okay. The music was melodic, peaceful, and played with passion by the student musicians. I tried to follow along and thought I did fairly well for the first couple of concerts, but then my mind began to wander, and I almost fell asleep during one of the recitals. Science courses and labs took up all my time, and I think that an innate appreciation of classical music was not in the cards for me. Susan soon realized this, and I stopped attending those recitals with her. Occasionally, I could pick up an R&B radio station from Philadelphia on my clock radio, so she soon figured out that I was much more appreciative of this type of music. She even told one of her other acquaintances that she had a roommate who also loved this music genre. This acquaintance eventually came to our room to meet me, but lost her enthusiasm at possibly finding a kindred spirit when she discovered that I was a Negro. Susan thought that this was funny, but also very hypocritical of her acquaintance, whom she never mentioned again. I think that this was also around the time when B’nai B’rith, the oldest Jewish service organization in the world (who had written a letter to welcome me to the campus before I arrived and before our pictures were printed in the Cygnet), also rejected me by not initiating any further contact after they realized that I did not fit the expectations raised by my surname. Fitting into campus life was going to be harder than I expected.

My response to African and Caribbean music was entirely different. I felt as though I was at home. Through Bridget, I met Jannette who introduced me to music from NYC and the islands that I had never heard before—calypso, soca, and black American artists like Arthur Prysock, Nina Simone, Lou Rawls, and Nancy Wilson. The music of my childhood was southern R&B—James Brown, Carla Thomas, Otis Redding, Motown sounds, blues singers like Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, and, of course, gospel music. When I finally got to hear African music and see African dance, I knew that I had found the original source of the music and rhythm that I loved. One of the first things that I bought with my own money was a record player, followed by albums. I picked up the habit of grazing record stores on a regular basis, a practice I continued throughout medical school, well into my late twenties.

At the end of my second month at Swarthmore, on my eighteenth birthday, I was still hanging out with my roommate from Ohio, wearing my “preppy” clothes and penny loafers, and trying to find my place at Swarthmore. I came back from my afternoon classes to find a surprise that I have not forgotten after all these years. I even have a picture of it: me in an A-line, sleeveless, green floral dress, a permed, mid-length page boy cut hair with bangs, and a forest green glass vase/jar that was placed on the top of my dresser in the left-hand corner. I was smiling a big, open-tooth smile and blowing out the candles on a cake that had been delivered for my birthday. My mother had arranged to have a birthday cake complete with candles and a birthday card delivered to my dorm room. I was pleasantly surprised and pleased that my special day had not been forgotten. I remember how grown up and loved I felt.

I came to Swarthmore to study science, preferably chemistry, because my mother taught high school biology and I saw myself as destined to teach high school chemistry. My mother had a good life as she went to work, made money, and had some level of independence in spite of having a husband and four children. I never saw myself as being married or having children—that was for the normal pretty girls. I knew that I would always have to take care of myself and thought that teaching high school would do the trick for me. I loved science, and still do, but I was surprised at the joy and opening of the spirit that I felt in English class.

The great awakening occurred in second semester of sophomore year: fourth semester of math, calculus, second semester of physics, and second semester of physical chemistry. I barely made it out of those courses alive. These courses would “separate the men from the boys,” the true scientists and mathematicians from the wannabes. It was clear that I was not a real scientist. As I looked around for another path, my friendship with several of the postbaccalaureate students (most of them were HBCU graduates who were spending an academic enrichment year at Swarthmore, usually as a pathway to additional degrees), showed me the way.

Female physicians were unknown in my world and seemed mythical to me, even if Bridget and Susan had originally expressed interest in this profession, but I thought that if a post BACC could get into medical school and become a doctor, so could I. I changed course and took biology classes, eventually earning majors in both chemistry and biology. The path was smooth and the detour almost imperceptible, but I knew that medical school was the way forward.

Sharples Dining Hall and the Beginning of Black Consciousness