Читать книгу Seven Sisters and a Brother - Joyce Frisby Baynes - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

We all met between 1965 and 1966 as undergraduates at the highly selective Swarthmore College in the suburbs of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was a time when elite colleges were just beginning to enroll significant numbers of blacks, several being first-generation college students.

We were seven young women and one young man from diverse families and backgrounds. We developed enduring friendships tightly intertwined with activism through the Swarthmore Afro-American Students Society (SASS) which we organized with like-minded black students on campus.

We didn’t know that our bond would take on almost mythical proportions and remain in the minds of generations of black students. The legends that emerged did not include our real names, and few knew anything about us as individuals, our motivations, our hometowns, or our stories. Little changed until 2009, on the fortieth anniversary of SASS, when the current black students at Swarthmore invited us to tell them about the founding of the organization.

They had not known about us as Joyce and Marilyn A., who became mathematics majors; Jannette, a political science/international relations major; Marilyn H., an economics major; Bridget and Myra, biology and chemistry majors, respectively; and Aundrea, a sociology and anthropology major. One of the revelations in this telling of our stories is that they didn’t know Harold, another mathematics major, was also an integral part of our group.

They had not heard how we drew on our family and spiritual roots and reached out to the black adults from nearby communities for strength and, ultimately, for rescue. They only knew that we called for black contributions to be represented in classrooms, campus culture, student life, and college faculty and administration, and that, eventually, we took over a major campus space to ensure those demands were taken seriously. That Takeover brought all academic activity to a halt to focus on our demands until a completely unexpected tragedy ended our action abruptly.

Some of the students at the fortieth anniversary event had heard that the period between 1967 and 1970 saw black student protests on hundreds of campuses. Indeed, some of their parents had been involved in these protests, but they had no way of knowing how much the actions at the College we attended were inspired by or looked like what happened elsewhere.

When we gathered at the College all those decades later to share what happened, the rapport that we had developed as undergraduates was still evident among us. We had the mutual trust to tackle and achieve the formidable task of recapturing our stories, some of them shrouded in inaccurate reporting and many others discarded over decades, buried under the dust of history.

After the anniversary reunion, the two Marilyns and Joyce returned home and began to carve out time to capture their memories; however, opportunities to do so always seemed elusive, and not being professional historians or writers, we despaired that we didn’t have the resources to do the stories justice. Marilyn A. contacted black faculty to see if there was a current history major who might tackle the task as a research project.

Five years later, with the support of the College’s then-President Rebecca Chopp and Dr. Allison Dorsey, a history professor and then-chair of the Black Studies Program, the College mobilized resources to offer a one-time course entitled “Black Liberation 1969.” For their rigorous historical research into the events surrounding “the Crisis,” students reached out to us and our contemporaries for photographs, artifacts, and interviews, and digitized the materials for permanent online access.

President Chopp’s support of that research and her formal invitation to return to campus deeply moved us. We had lived to see Swarthmore College acknowledge that what we had done had been a gift to the institution, exactly as we had conceived our actions to be, despite all the negative press to the contrary at the time.

As the College honors its 150th anniversary, or sesquicentennial, we seek to examine our history critically and with self-reflection…

…to specifically examine events at Swarthmore in 1969 that led to the creation of the Black Cultural Center, the formation of Black Studies at Swarthmore, and ultimately, to a much more vibrant, diverse, and inclusive campus environment.

…your involvement at this pivotal juncture in the College’s history is a critical part… Your story has not been documented formally, even though it is important to anyone who truly wants to understand how the Civil Rights Movement was reflected on Swarthmore’s campus. Your activism paved the way for generations of students who now enjoy the fruits of your labor and who…continue to carry your torch…

Because your story is so important to our understanding of Swarthmore’s history, I write to invite you…to come to campus Garnet Homecoming and Family Weekend…

[Your story will be] stored in McCabe Library, so that your [legacies] are forever a part of Swarthmore’s narrative…

I hope you will consider this invitation and the powerful impact your presence would have for our students and all of us here at the College.1

In the 2014 sesquicentennial anniversary celebration, a chapter of the book published for the occasion, Crisis and Change, begins with this statement:

Institutions can seldom identify a specific moment when they changed direction, but it’s arguable that the Swarthmore College we see today—rigorous, creative, accessible, diverse, and committed to civic and social responsibility—issued from the eight-day crisis that rocked the institution in January 1969.2

Seeing the College acknowledge that the “eight-day crisis” was central to “the College we see today”—and knowing that the eight of us were at the heart of it—were key catalysts for us getting more serious to record our memories of it. We knew that we had a story to tell, and we had seen prior attempts by others that focused on the “Crisis” as it impacted the College, but did not adequately explore our motivations and actions.

In individual and group dialogue with the young researchers, we made it clear that Quaker values were, implicitly or explicitly, a key factor in choosing Swarthmore for our education. Academic rigor was another key factor. We were not afraid of a challenge. We had not, however, expected that head-on confrontation with the College administration would be the major challenge that it proved to be. Unbeknownst to us, the College was considerably reluctant to accept many of us. Some institutional leaders had expressed concern that we would not and perhaps could not perform up to their standards. Through our actions during the development of SASS, we challenged the administration as equals. In the end, we demonstrated not only that students of color could be the equals of white students, but that we even had something to teach “the adults.”

The strong interest of the current generation of students in understanding how and why we were able to do what we did made it clear that we needed to spend time getting back in touch with our youthful selves and reconnecting with the history we had created. When and how to do this? Marilyn H. suggested we meet in Panama, so Bridget could join us, as that was where she lived at the time. So, the next summer, after the sesquicentennial, we met in Panama, with several spouses, and began to document our experiences. The dynamics among us and the drive within us were the same as they were fifty years prior.

As we swapped life stories under cool breezes in tropical Panama City, we were stunned at the many commonalities in our backgrounds that we had not recognized before. Over a three-year period, we embarked on writing our individual and collective memories, and it became clearer why we bonded into an extended family on campus, and how activism in our individual lives since college continues and extends what we did there. The good news is that what we discovered is not specific to our era, but is accessible to any generation. We believe our narratives will answer questions the current college generation, and even our peers, have asked us, and will inspire and empower them and others.

As we unearthed memories during those Panama conversations, we arranged many versions of our common college experiences into piles and sorted them into themes. The most dramatic entries told about the January 1969 Takeover, but we became convinced that the Takeover happened only because of the metamorphoses in our individual lives. So, we interspersed the chronology among narratives of family, first encounters with the College, and lives changed as a result.

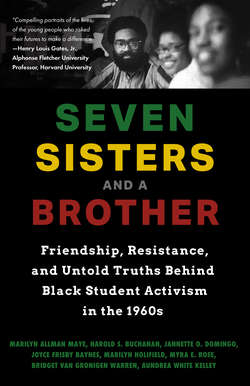

Writing a choral memoir matches the way we have always worked together: collaborating in analyzing our situation, planning solutions together, communicating in combined voices, and avoiding highlighting a single leader. This, then, is our shared story. The story of Seven Sisters and a Brother.