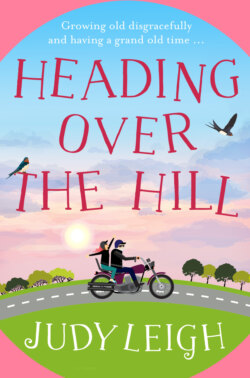

Читать книгу Heading Over the Hill - Judy Leigh - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

Оглавление‘Maggot Street? You have to be kidding me, Billy.’

Billy clutched the steering wheel of the old Transit, swinging the van around a corner, and then whirled his eyes towards his wife, who was huddled next to him, her purple lace-up boots on the dashboard. ‘Margot Street, darlin’. Mar-go. As in Margot Fonteyne, the famous classical ballet dancer of the 1960s.’

‘As in “Am Mar-go-ing to like this place?” I don’t think so at all.’ They turned the bend too sharply and, as Dawnie indicated the maze of houses on the estate, she leaned across to Billy, almost obstructing his vision, her voice incredulous. ‘Look at it, Billy. It’s just a pile of boring terraced houses.’

Billy grinned, extending a hand to pat Dawnie’s knee. ‘It’s just a six-month let, my darlin’. The first of May to the last day of October, with an option to stay on if we need to. I just went online, like we agreed, and picked something convenient and cheap for us, just for now. We’ll take our time to buy the house we really want – a big rambling one, on the coast looking over the rolling waves, in time for Christmas. Log fire, beams on the ceilings. It’ll all be just dandy.’

Dawnie wrinkled her nose in answer. ‘I thought it’d be great to live here in Barnstaple, by the sea, away from the frozen north. I thought it’d be a great place for two seventy-year-old misfit hippies to do our own thing in the wilds of north Devon. But this group of identical terraces, Billy: look at it. It’s all net curtains and plastic faux-wood front doors. The residents are going to hate us here.’

‘Don’t fret, my pet,’ Billy chuckled. ‘It’ll be deadly. Think about the advantages. Lindy and Stewie and the kids have our house in Bolton. It’s big and ramshackle and ideal for them – so close to the shops and schools. And now my da’s money is in the bank from his place in County Mayo, God rest his soul, so that makes us cash buyers. We can pick wherever we want. And I want something peaceful, where we can hear the sea when we open the window and look up at the moon.’ Billy stared at her meaningfully, raising his bushy eyebrows. ‘We’re in charge of our lives for once. The kids are settled; it’s a new start for us, and the pictures of the seaside properties on the internet look grand. We came here years ago and loved it: remember that summer in Staunton Sands when the kiddies were little? And if the worst comes to the worst and we don’t like it here or we can’t find the place we want by the end of six months—’ He gave a big shrug, his shoulders moving like two giant hills. ‘Then we can move on again. We could always go to Ireland. I’ve still a cousin over there.’

‘I’ve got nothing against this area: it’s just this horrible street. Look at it,’ Dawnie exploded, scratching her head. She was wearing the long blonde wig today and her scarlet sunglasses; she thought she’d dressed perfectly for the early summer sunshine that glinted and dazzled her through the windscreen of the red Transit. But now she wasn’t sure, staring out of the window at this tidy row of terraces, net curtains at the windows, neat hanging baskets by the doors. People could be quick to judge. Then she folded her arms, came to a decision and let out a long breath. ‘Oh, sod them all, Billy. I mean, if the neighbours are going to dislike us just because of your long hair and leather jacket and my wild wardrobe, then they aren’t worth worrying about.’

Billy rolled the Transit around another bend into a narrow row of neat terraces. ‘I bet they’re all lovely people, darlin’. You just have to trust in the beauty of human nature. I’m sure they’ll all be wonderful, our new neighbours.’

Dawnie slid the red glasses up onto her forehead and beamed at him. ‘Ah, you’re right, Billy, as usual. We’re going to love it here. And here we are – look: this one is ours, the cute little brick one right in the middle with the white plastic door. Number thirteen, Maggot Street.’

The floral curtains on the upstairs landing window of number eleven Margot Street twitched briefly. A hand held the material back, leaving a gap just wide enough to peek through. A man in his seventies, his hair grey-brown and thinning on top, peered through his spectacles with eager eyes as he leaned forward. A woman appeared behind him, resting her chin on her palm and frowning. She was considerably shorter than him, her ample figure encased in a flowery dress not dissimilar to the curtain material. At the end of her legs, which were sheathed in tan-coloured nylon tights, was a pair of comfortable brown slippers. She leaned closer. ‘Is that them, Malcolm? Our new neighbours?’

‘I certainly hope not. It’s a red Transit van. Must be builders come to make good any damage left by the students, or whatever those three young men were who lived there before.’

‘Darren and Jason and the other one? Oh, I’m so glad they are gone. The smells that used to come through the walls sometimes – awful smells. Goodness knows what those young men used to cook: all sorts of strange ingredients, no doubt.’

‘They were probably smoking cannabis – especially if they were students.’ Malcolm didn’t move. ‘Or cooking foreign food. I don’t like foreign food.’ He sniffed. ‘Apparently the new tenants are an older couple. Perhaps they’re our age, Gillian. In their seventies. Sensible people who – oh, my goodness.’

‘What is it, Malcolm?’ Gillian patted her short white hair to check the hairspray had kept it in stiffly in place. ‘Can you see them?’

‘There’s a man, the driver, in a leather jacket. He has long grey hair in a big ponytail. He looks like a thug; he’s huge. He’s going to the back of the van and he’s getting something out – something large, I think – goodness me, is that a motorcycle in there?’

‘Let me see, Malcolm, You’re in the way. I can’t see.’

‘Don’t push me, Gillian. Wait your turn. It can’t be the new neighbours. Oh, he’s getting luggage out of the van first. There’s someone coming to help him…’

‘Is it them?’ Gillian craned her neck. ‘Is it the new people, moving in next door?’

‘Oh, will you look at that woman?’ Malcolm caught his breath.

Gillian assumed he’d seen an attractive woman and was ogling her. She pushed her husband to one side. ‘Let me see.’

A woman in a red mini dress and a denim jacket appeared around the side of the van. At the end of long skinny legs, she wore huge purple lace-up boots and her flowing blonde hair came almost to her waist. She was tugging a large case.

Malcolm coughed. ‘Well, would you believe it? She’s no spring chicken…’

‘And dressed like that – just look at her,’ Gillian muttered.

They stared together, their hands gripping the curtains. Then, at the same time, they caught their breath and jerked backwards, almost slipping down the stairs. The blonde woman had seen them; she was staring up through red sunglasses and was smiling, waving her hand maniacally and yelling, ‘Yoo-hoo. Hello, we’ve arrived.’

Malcolm tutted softly to himself. ‘No, Gillian – that’s not them. There must be a mistake. They surely can’t be the new neighbours.’

Across the road at number fourteen, a dark-haired man in his early fifties was putting out the recycling boxes, which were stacked with folded cardboard. It was a job he liked to make sure was completed early, in case he forgot to do it. Work at the garden centre was hectic during the summer months and it was important to have a routine for everyday jobs like dustbins. He couldn’t ask his mother to do strenuous chores. Besides, he was strong: he worked out regularly, so it made sense for him to take out the bins. He placed two green plastic crates carefully, one on top of the other, adjusted his tie and pushed his hands into his pockets.

He frowned. Two people had just emerged from the red Transit across the road. A large man with long grey hair tied in a ponytail, wearing a leather jacket and jeans, was rolling a motorbike down two planks of wood, grunting. The dark-haired man paused, shoved his hands deeply into the pockets of his loose trousers and squinted, staring across the road. His mother would be calling him for her second cup of tea but he wanted to find out who the neighbours were. He’d make her a drink as soon as he went inside: at eighty-six, she had every right to be demanding. He leaned forward, watching the big man grunt and struggle. The man caught his eye and smiled across, shouting something that sounded a little like, ‘Will you give me a hand here?’

He had an accent, Irish or Scottish; the dark-haired man thought he must be from somewhere in the far north. It might be safer for the time being to pretend he hadn’t understood. He shrugged and fiddled with the cardboard in the recycling box, neatening the edges. A voice called to him from inside the house, his mother’s voice, the tone firm despite her advanced years. He could hear her distinctly.

‘Vinnie, can you come back in here, love? It’s getting draughty with that door open. What are you doing out there for so long? Come on in, I need another cuppa.’

Vinnie straightened his tie and glanced in the direction of the struggling stranger and the motorbike. It was a classic, the machine; glossy black paint, with beautifully chromed forks and spokes. Vinnie nodded: it was a lovely bike, and he imagined how nice it would feel to own one. For a moment, he was astride the machine, aviator sunglasses on his face, the engine rumbling between his knees, cruising along the road to the soundtrack of ‘Born to be Wild’. He imagined his dark curls lifted on the breeze, his frame encased in leather. It would be good to own a bike, to feel the wind in his hair, to be independent.

Suddenly, he heard a shriek and he lurched backwards. A woman in a red mini dress, her blonde hair almost to her waist, had joined the man and was laughing, shrieking something towards the upstairs window of number eleven, helping the man to steady the motorbike. She jerked her head to look at Vinnie and his mouth dropped open. Behind the sunglasses, the woman was no youngster: she was older than him, probably, and he was fifty-two. He gasped, as she caught his eye and waved a hand wildly.

‘Ey-up, handsome,’ she shrilled. Vinnie felt his heart lurch. She had a northern accent and clearly wasn’t lacking in confidence. ‘You could pop over and give us a hand rather than just stand there gawping. If you keep staring at me like that, the wind will catch you with your gob open and you’ll stop like that forever.’

The man with the ponytail mumbled something to her, his voice a soft rumble. Vinnie didn’t wait to find out what he was saying. The man was big and burly and might be dangerous. Vinnie knew it was safer to walk away from confrontation. He twisted round, called, ‘Just coming, Mam,’ and ambled into the house. As he closed the door, he could hear the woman’s voice chuckling, peals of loud laughter in his ears. He could never tell what women meant when they laughed like that. Sometimes it meant that they were attracted to you. After all, she had invited him over and called him handsome. For a fleeting moment, Vinnie wondered if the blonde woman had been the big biker’s wife. But she was more likely to be his sister or his friend. She had paid Vinnie a compliment in front of the big man: if she was his wife, she’d never have done that.

Vinnie paused in the hallway and felt his heart lurch. He had been loved more than once. More than one woman had stroked his soft curls and commented on the beauty of his huge brown eyes and long lashes. But there was no one now, no one to whisper words of affection in his ear. The women at the garden centre were mostly married or too young for him. Vinnie shivered. He wondered if the blonde woman had found him attractive and wanted to get to know him. But it was hard to read what women meant when they gave you their full attention like that. Sometimes it meant they liked you; sometimes it meant that they liked you a lot. Vinnie scratched his scalp through the soft curls and wandered into the lounge to see what his mother wanted.

Dawnie watched the man rush back into his house across the street, slamming the door behind him. Laughter spluttered from her mouth. ‘I’ve upset one of them already.’

Billy wrapped a bear-sized arm around her. ‘Ah, but you couldn’t upset anyone, darlin’. We’ll get the Harley inside, will we? Then perhaps we can have a good look round the house, get our bearings. I’m hungry.’

‘And I’m dying for a brew, gasping. Come on then, Billy. Steady as she goes.’

They pushed the motorbike, Billy guiding the handlebars and Dawnie shoving the seat from behind. It fitted well enough into the hallway, with enough space for a human, even Billy’s size, to squeeze through the gap. Billy closed the front door with a dull clunk and took Dawnie’s hand.

‘The bike’s safe now. It won’t be stolen, locked in here with me. But we’ll get a big garage in the next place.’ Billy gave Dawnie a sheepish grin. ‘This is our home, my darlin’ – for the next few months. Tell me, how well has your husband chosen?’

‘Maybe I shouldn’t have left it all to you.’ Dawnie screwed up her face. The lounge smelled musty. There was a blue sofabed, faux-leather and squishy enough. The TV was nothing special, not like the huge one with surround sound they’d left at home for Lindy and her family. The mantelpiece was old-fashioned white tiles, and below it was a gas fire. Dawnie sniffed meaningfully, wrinkling her nose in disgust, and tugged Billy into the kitchen. It was old-fashioned and poky; the white cooker had clearly not been cared for. The gas rings were rusty and there was still a circle of dried-on gravy encrusting the enamel. The floor was covered in thin linoleum in a black and white square pattern, like a tattered chess board. There was a small fridge, a microwave, an old washing machine and a scratched stainless steel sink with a dripping tap.

Billy grabbed her in a little waltz. ‘We can cook up a storm in here.’

‘It reminds me of my mother’s old place in Daubhill years ago. The style is the same 1950s chic.’ Dawnie planted a little kiss on Billy’s nose. ‘But home is where you are, my lover. I’ll get my own stuff in here and maybe we can chuck some paint on a wall or two, change the curtains and…’

‘And it’ll be grand, while we look for the place of our dreams… It’s what we need, darlin’. Our own place – me and you and some peace and quiet.’

Dawnie forced a smile. ‘Peace at last, just the two of us, Billy, you and me…’ She cuddled up to him as he wrapped her in a bear hug. She was thinking about her daughter Lindy Lou and Lindy’s husband Stewie and their daughter Fallon and her three children at the rambling Victorian semi in Little Lever. She imagined baby Milo, his face contorted, screeching as he often did, and seven-year-old Willow throwing a tantrum as she smeared her mouth with her mother’s crimson lipstick. This house felt too small, too quiet in comparison. It was going to be difficult living so far away from her huge brood. Dawnie forced a quick grin, wriggling closer into Billy’s warm embrace.

‘Home is where you are, Billy. And it’s the beginning of a new adventure. We’ve talked about it for ages: the sea and how it’ll bring you some calm and you’ll sleep better. I’ll miss the old place I expect, from time to time, but this is only temporary, and it’ll give us time to get to know the area. Yes.’ She smiled up at him. ‘This is perfect for now. Let’s phone for a takeaway. There must be somewhere local, and we can crack open a bottle. What do you think?’

Billy lifted her up with ease and, as the mini dress hitched itself further up her thighs, she wrapped bare legs around him. ‘I think I’m the luckiest man in the world.’ He kissed her lips. ‘My lovely wife.’

She nibbled his ear, her voice deliberately provocative, teasing him. ‘We haven’t checked the bedroom yet.’

Billy chuckled, a deep grumble from beneath his ribs. ‘I hope there’s a good bed upstairs. The one online on the landlord’s photo looked strong enough to take an eighteen stone man… and his seven and a half stone woman…’

‘I’m eight stone two.’ She wriggled down from his grasp, adjusted the blonde wig so it sat straight on her head and then grinned. ‘We’d better give it the once over, though.’ She cocked her head to one side. ‘Come on then, Billy, I’ll chase you up the stairs.’

He turned to go just as the bell chimed two long notes in a deafening ding-dong. Billy turned to his wife, his forehead creased in confusion. ‘Well, and who can that be now? We’ve just moved in… and we don’t know anybody.’