Читать книгу Heading Over the Hill - Judy Leigh - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

Оглавление‘Your boiled egg is ready, Malcolm.’

His thin fingers twitched at the curtains. ‘Just a minute.’

Gillian picked up a cloth and wiped it across the marbled work top, scrubbing at imaginary crumbs. Then she reached for the teapot. Her short white curls were tidily brushed and fastened with a neat hair grip at one side, to prevent them falling across her forehead. ‘Malcolm.’ She poured weak tea into china cups and added milk. ‘Your three-minute egg…’

‘All right, Gillian.’ The tense note in his voice told her to refrain from further cajoling or nagging: he would often say, ‘You’re nagging me again, Gillian.’ She sighed and sat down, cutting the top of her egg with a small knife and watching the golden yolk drip over the side of the small egg cup. She wondered whether to reach for a napkin and wipe it clean.

Malcolm leaned forward and pressed his nose against the living room window. He adjusted his glasses, and blinked. ‘He’s out there again. He’s getting something out of the van.’

Gillian opened a packet of butter carefully. With precision, she scraped a tiny amount and pressed it on a slice of pale toast, staring at the table in front of her.

‘What’s he got? It looks like a box, a big square box. He’s getting it out. He’s carrying it into the house. It looks heavy and precious. He’s carrying it very carefully.’

‘I’m not sure about that note you sent last night, Malcolm. It wasn’t very neighbourly.’

‘If he doesn’t move that van today, I’ll be true to my word, I’ll ring… oh, good God.’

‘What is it, dear?’

‘There’s a woman out there with him.’

‘The blonde one in the mini dress?’

‘No, another one. She must have a twin: this one is just as small and skinny but she has long black hair, and she’s wearing a pair of tight leather trousers. Not very seemly.’

‘Malcolm…’

‘Come and look, Gillian. I think he might have two wives. A bigamist: perhaps that’s what he is.’

Gillian took a bite of toast. ‘Your egg…’

‘Good Lord, she’s carrying a cymbal.’

‘What sort of symbol, Malcolm? Do you think they are druids? Warlocks?’

‘It’s some sort of drum-shaped thing, Gillian. I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s not one of those dodgy antique dealers who do the shabby chic stuff – you know, coffee tables made out of old tyres and recycled trash. That sort of thing.’

‘Come and have your breakfast, dear.’

Malcolm turned. His brow was furrowed beneath the thin grey hair. His dark suit, grey shirt and tie were impeccable, but his clothes hung from his frame, sparse and ill-fitting. He groaned. ‘I have a bad feeling about these neighbours, Gillian. A bigamist who deals in dubious antiques, that’s what we have living next door to us now. And he must be at least six feet four, with all that hair and a big beard. It’s a worry. I mean – this is our home.’

Gillian offered him a smile as weak as the tea. He moved slowly towards the table. ‘They aren’t young people. He must be sixty-something at least. Almost as old as we are, Gillian.’

She nibbled a piece of pallid toast. ‘I’m seventy-four.’

He sat down sadly. ‘They’re old enough to know better, not to behave like teenagers, like students.’ He bashed his egg with a spoon, cracking the shell open. Inside, the yolk was deep yellow and hard. ‘I’m not going to put up with any nonsense, Gillian. I’m going to write it all down in a list. Day one, large newcomer parks too close to our parking space and it would be difficult to get the Honda Jazz out. He then takes a motorcycle into the house. Day two, bigamist neighbour brings junk and antiques into the house, probably bought from a dubious source. I’ll log it all down, every day.’ Malcolm lifted his cup and took a sip of tea. It was tasteless and tepid.

They chewed in silence, Gillian thinking about the white carpet that covered the whole floor in the lounge and kitchen diner, and how it needed hoovering. She was proud of the fact that she cleaned each day. The roast needed to be put in the oven soon: Malcolm liked his meat well-cooked and his roast potatoes crisp on the outside. She wondered whether to make a fruit crumble for pudding or whether to offer ice cream from the freezer. She glanced across at the mantelpiece, at a photograph of a young man in uniform, and sighed. It was best to put James out of her mind this morning and concentrate on getting things done.

Malcolm was planning a file on the neighbours. He would begin it today, filling in yesterday retrospectively. He would write it all by hand, logging activities and the times they occurred. It was a shame, he thought, that he didn’t own a mobile telephone, as he could take photos on one, although he wasn’t quite sure how it worked. He could use a computer – he had one in the third bedroom, now his office – but it was only for emailing and researching. Technology didn’t interest him much, although now he could see a use for it. He had a video camera somewhere, probably in the loft: that might be useful for filming the neighbours. He could film them from the landing window and achieve a reasonable angle without being noticed. Malcolm frowned at the thought of the footage of Billy he might get, the sort of antisocial or illegal behaviour he could capture on film.

Gillian interrupted his thoughts. ‘Have you eaten enough, dear? You haven’t finished your egg.’

He grunted. ‘The yolk was hard. It was overcooked, Gillian.’

Suddenly, the door knocker echoed loudly: there was someone outside, bashing at the door. Malcolm sat bolt upright. Gillian glanced at him, her eyes wide. ‘Who’s that?’

Malcolm moved swiftly to the window, edging behind the curtains and peering out like a secret agent. He took a deep breath. On the other side of the net curtains, he could see two figures. One was the woman in leather trousers and a matching jacket, her hair a mass of black curls to her shoulders. She was wearing a pair of heart-shaped sunglasses in lurid blue. The other was the big man, his hair, now free of the ponytail, reaching his shoulders in grey unruly curls. He was carrying a plastic bag. Malcolm kept his voice low. ‘It’s them.’

‘Who? Who?’

‘Shhh, Gillian, you sound like an owl.’ Malcolm adjusted his position. ‘It’s the big man next door and his second wife. And they’ve got something in a bag.’

Her voice rose. ‘A gun? A dead animal?’

Malcolm frowned. Gillian had been watching too many detective programmes on television. The door knocker resounded again, louder. Malcolm could see the huge giant of a man in his leather jacket and dark jeans lift a ham-sized fist to make himself heard. The woman said something and laughed. Malcolm held his breath.

‘Don’t answer it, dear.’ Gillian’s voice was a low hiss.

‘I don’t intend to. He might be dangerous,’ Malcolm whispered back, his eyes wild.

There was no sound for a while except the persistent ticking of the clock on the mantelpiece. Then Malcolm breathed out. ‘They’re moving away.’

‘Back to their house?’

‘Yes. No. Good Lord.’

‘What’s happening, Malcolm?’

‘It’s the woman. She’s taken the bag off him. She’s going across the road. Oh, Vinnie Stocker is outside his house at number fourteen. He’s putting out more rubbish into the recycling bins although I’ve no idea why he does that at the weekends since the bin men don’t come until Monday. Oh, she’s talking to him. He’s talking back. The big man has gone over to join them. The big chap is shaking his hand and giving him the plastic bag.’

Malcolm felt a light touch on his shoulder. Gillian had come to stand behind him. ‘What’s in the bag, do you think, dear? Drugs?’

‘I dread to think. He was going to offer it to us. Whatever he has in that bag, it doesn’t bode well. I’ll update my file: neighbour and second wife offering unknown substance to other neighbour in broad daylight.’

Across the road, Vinnie peered inside the plastic bag. ‘Thank you. Is it, you know, Irish?’

Dawnie giggled. ‘It’s stout, if that’s what you mean. Packs a proper punch, though.’

‘It does, for sure,’ Billy nodded. ‘I have gallons of the stuff under the stairs. I make it myself. It’s nice to have a bottle or two of a night, while I’m watching TV.’

‘I’m partial to a bit of beer. My mam likes milk stout.’ Vinnie’s face was anxious as he clutched the bag of bottles to his chest. He scratched his dark hair, pushing back a long fringe that almost covered his eyes. ‘She likes port, too.’

‘Well, try her on the home brew,’ Billy suggested. ‘If she likes it, I’ll bring her a few bottles round.’

Vinnie smiled at his new neighbours, glad of their company. ‘Thank you,’ he muttered. ‘Oh, and I’m Vinnie Stocker by the way. Vinnie, most people call me, although I was christened Vincent. Vincent David Thomas Stocker. My mum’s Dilys Stocker, Dilly, she’s eighty-six.’

‘She won’t thank you for telling us that.’ Dawnie held out her hand. ‘Maybe we can meet her next time. I’m Dawnie Smith and my husband is Billy Murphy.’

Vinnie shook her hand and glanced at Billy. ‘Irish. I see.’ He brought his lips together and nodded. ‘Billy. Dawnie.’

‘You’re lucky our neighbours weren’t in,’ Billy chuckled. ‘I already gave a few bottles to the ladies in number fifteen. But the man at number eleven was out and then you came outside…’

‘Didn’t we see you yesterday?’ Dawnie pushed her black curls back from her face and adjusted the sunglasses.

Vinnie frowned. The woman who had shouted to him yesterday, who had paid him her full attention, had been a blonde. Dawnie was very similar to her: Vinnie assumed there must have been two women, sisters perhaps, with different coloured hair. Dawnie, the dark one, was the wife and the blonde one was Billy’s sister-in-law. He wondered where the blonde sister was at the moment, and how he might ask the questions about where she lived and if she was single.

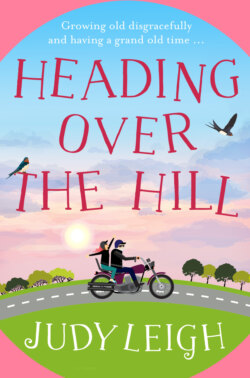

Billy wrapped an arm around Dawnie. ‘Right, darlin’. We’re off on the bike after I’ve sorted the carburettor. It’s a lovely day for it.’

Vinnie breathed. ‘You have a Harley Davidson. I’d love to see it properly, close-up…’

‘Right you are, Vinnie, I’ll give you a shout and you can come and help me do a couple of little jobs. I clean and polish it every Sunday.’ Billy patted his shoulder and Vinnie winced.

Dawnie brayed loudly. ‘Maintaining the bike is more important than cleaning the house. Come on then, Billy. Let’s get organised and then we can head off to the coast.’

Vinnie watched them turn and walk back to number thirteen, their arms around each other. He wondered if he had made friends. He smiled and, as he turned back to the house, he began singing to himself. It was the chorus of ‘Born to be Wild’. As he disappeared into the darkness, he made some low motorbike sound effects, imagining Dawn’s lovely sister clinging to him as he roared along the road on his own bike, and his grin broadened.

Vinnie placed the bottles in the kitchen. ‘I’m here, Mam. Do you need anything?’

His mother’s voice had a soft Welsh lilt. ‘Come in and close the door, Vinnie. I’m freezing in here.’

Vinnie was thoughtful for a moment. The woman with black curly hair, Dawnie, was Billy’s wife; the blonde woman in the mini dress, the sister who called to him yesterday, must definitely be single and interested in him. She had called him handsome. He wondered if she lived with them, the blonde. She was attractive, full of energy. Vinnie wondered what her name was. He hoped she might be looking for love. A soaring feeling lifted his lungs, a little bit like bubbles or a happy tune, and he imagined himself friends with Billy, helping him with the Harley Davidson, going for a ride as a pillion passenger, having dinner with Billy and Dawnie and meeting the blonde sister and falling in love with her.

It would be good to have someone to care for. It had been a while since Sally. He had loved Sally best, and she had hurt him the most. She had turned out to be everything his mother had warned him about. But there had been others he had loved too, loved and lost, because, as his mother often told him, he picked girls who were fickle. But maybe Dawnie’s sister was looking for true love.

Vinnie worried about his mother for a moment. She depended on him. But if he married the blonde sister, perhaps they could both live with his mother. Vinnie hoped they’d all get on. He wandered into the lounge. His mother was listening to a news programme on the radio, huddled in the armchair. She was a small woman but she was not frail. She wore comfortable trousers, a loose sweater and a pair of heavy-framed glasses and her hair was long and pale, wound around her head and fastened with a clip.

‘Where have you been, Vinnie? I do wish you wouldn’t leave the door open, mind. It gets so draughty in here with it all open.’ Dilly tugged at the rug over her knees to prove the point.

‘Sorry, Mam.’

‘I thought I’d make us a lovely shepherd’s pie for lunch. There’s some meat in the fridge, I think.’

‘I can do it, Mam.’

‘Don’t be silly. I may be in my eighties, but I’m not senile. I can move about this house as fast as you can when I put my mind to it.’

‘Just trying to help, Mam.’

‘Well, don’t make me feel like I’m decrepit. I’m not. Just make sure I don’t bump into the furniture, mind, or forget anything, that’s your job. What were you doing outside all this time?’

‘I was talking to the new people over at number thirteen. They seem nice.’ Vinnie watched his mother’s reaction. She leaned forward, squinting at him with her good eye.

‘Who are they? Are they local people?’

‘No, he’s called Billy and he’s Irish, Mam. She’s from somewhere up north.’

‘She’s the cat’s mother, is she?’

‘Sorry, Mam, she’s called Dawnie.’

‘Young, are they?’

‘They might be my age, fifty-something, probably even older, in their sixties. I don’t know.’

‘What did they want then?’

‘He gave me some home brew. Stout. He makes it himself.’

‘What did he give you beer for? Is it no good?’

Vinnie beamed. ‘He says it’s lovely, Mam. He said we could have more if we like it. They are really nice. They’re going out for a ride on his motorbike, down to the sea. I think the woman called Dawnie has a sister.’

His mother stared at him. ‘Well, my boy, we’d better sample some of this lovely stout before I make lunch, I think.’ She wriggled in her seat. ‘Go and fetch two glasses, will you, and a bottle of your new friend Billy’s best beer. And while you’re at it, bring my eye drops.’

‘All right, Mam.’

Dilly watched him go, leaning forward. Her stronger eye was not too bad, but the other one was weak now, mostly just misty. She smiled. Vinnie was a good boy and she was lucky to have him home with her, helping her. But he needed friends: she could sense he was lonely and that she wasn’t enough for him, not really.

‘What would I do without you, Vinnie?’ she called out. She always told him the same thing and she meant every word. He was her treasure. She pulled the blanket over her knees. It was cold in the house, even though it was summer now. She wished she could go out and about more, like her neighbours across the road on the motorbike. It would be great to see the coast again and take in the scenery. Life was for living, she always said, but she wasn’t having the best of life, not nowadays. She was mostly indoors, in the armchair, squinting at the television.

She liked the action movies best: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Clint Eastwood, Sylvester Stallone and Bruce Willis. Without the television, life could be a bit dull, although Vinnie did his best for her. But there wasn’t much fun, not now. She was often tired at the end of the day, her limbs aching and stiff, and her movements were slower now than they used to be. She wasn’t sure how much longer she had left but she wished she could enjoy it all a bit more. She used to enjoy company, friends, going out, having fun. But those days were gone, in the distant past. She’d forgotten what it was like to have fun.