Читать книгу Invasion of the Sea - Jules Verne - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеiii The Escape

After the two officers, the sergeant, and the spahis had left, Horeb crept along the side of the well to a point where he could see up and down the path.

When the sound of footsteps had died out in both directions, the Targui motioned to his companions to follow him.

Djemma, her son, and Ahmet quickly joined him. They went up a narrow, winding street, lined with old, vacant, tumbledown houses, and made their way toward the bordj.

That part of the oasis was deserted, and the din of the more populous quarters could not be heard. It was pitch dark under the dense ceiling of clouds hanging motionless in the still air. The murmur of the surf on the beach, carried by the last breaths of wind off the sea, could barely be heard.

It took only a quarter of an hour for Horeb to reach the new rendezvous point, the lower room of a kind of café or cabaret run by a Levantine bazaar merchant who was part of the escape plot. His loyalty had been ensured by the payment of a substantial sum of money, which was to be doubled if the plan succeeded. His cooperation had already been very useful on this occasion.

Among the Tuareg gathered in the cabaret was Harrig, one of the most devoted and daring of Hadjar’s followers. A few days earlier, after a street brawl in Gabès, he had been arrested and imprisoned in the fort. During his time in the prison courtyard, he had been able to communicate freely with his leader. What could be more natural than that two men of the same race should associate with each other? No one knew that Harrig belonged to Hadjar’s band. He had managed to escape during the battle and fled with Djemma. Now that he was back in Gabès, according to the plan worked out by Sohar and Ahmet, he took advantage of his imprisonment to work out the details of Hadjar’s escape.

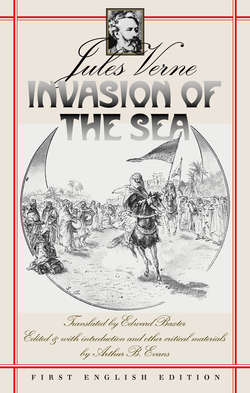

Arab homes in Gabès. (Photo by Soler, Tunis)

However, it was important that the Tuareg chieftan be set free before the arrival of the cruiser that would carry him away. And that vessel, which had been seen passing Cap Bon, was now about to drop anchor in the Gulf of Gabès. Hence the necessity for Harrig to get out of the bordj in time to coordinate his activities with those of his friends. The escape had to be carried out that very night. Once morning dawned, it would be too late. By sunrise Hadjar would have been taken aboard the Chanzy, and it would no longer be possible to wrest him from the hands of the military authorities.

This is where the bazaar merchant played his role. He knew the head guard of the military prison. The light sentence imposed on Harrig for his part in the street brawl had been served the previous day, but his companions were still waiting impatiently for him to be released. It was unlikely that his sentence had been extended for breaking some prison regulation, but it was nevertheless urgent that they know how things stood, and above all to make sure that Harrig would be released before nightfall.

The merchant decided to go and see the guard, who often relaxed at his café during his free time. That evening he set out for the fort.

Approaching the guard in this way, which might have aroused suspicion after the escape, proved to be unnecessary. As the merchant drew near the rear gate, he met a man in the street.

It was Harrig, and he recognized the Levantine. Since they were alone on the path leading down from the bordj, there was no danger of their being seen or overheard, let alone spied on or followed. Harrig was not an escaped convict, but a prisoner who had served his sentence and been released.

“What news of Hadjar?” was the merchant’s first question.

“He’s been told,” replied Harrig.

“Tonight?”

“Tonight. And Sohar, and Ahmet, and Horeb?”

“They’re waiting for you.”

Ten minutes later Harrig was with his comrades in the lower room of the café. As an extra precaution, one of them stayed outside to keep an eye on the road.

Less than an hour later, the old Tuareg woman and her son, with Horeb as their guide, entered the café. Harrig briefed them on the situation.

During his few days in prison, Harrig had spoken with Hadjar. There was nothing suspicious about two Tuareg, confined in the same prison, talking together. In any case, the Tuareg chieftain was to be sent off to Tunis shortly, while Harrig would soon be released.

Sohar was the first to question Harrig after Djemma and her companions had reached the merchant’s café.

“What news of my brother?”

“And my son?” added the old woman.

“Hadjar is aware of the situation,” replied Harrig. “Just as I was leaving the bordj, we heard the Chanzy fire her cannon. Hadjar knows he’ll be taken aboard tomorrow morning, and he’ll try to escape tonight.”

“If he put it off for twelve hours,” said Ahmet, “he’d be too late.”

“What if he doesn’t make it?” whispered Djemma.

“He’ll make it, with our help,” Harrig replied quickly.

“But how?” asked Sohar.

Harrig explained.

The cell where Hadjar spent his nights was in a part of the fort facing the sea, so close that the water of the gulf lapped at its base. Adjoining this cell was a narrow courtyard, accessible to the prisoner, but surrounded by high, impassable walls.

In one corner of the courtyard was an opening, a sort of drain, leading to the outside and blocked by a metal grating. The other end of the drain was about a dozen feet above sea level.

Hadjar had noticed that the grating was in poor condition and that its bars were rusting from the effect of the salt air. It would not be difficult to pry it loose during the night and crawl through to the outside.

But how could Hadjar make good his escape after that? If he dropped into the sea, would he be able to swim around the edge of the fort to the nearest beach? Was he young and strong enough to take his chances with the powerful gulf currents running out to sea?

The Tuareg chieftain was not yet forty years old. He was a tall man, white-skinned, but tanned by the fiery African sun, lean, strong, accustomed to all forms of physical exertion. Given the general sobriety of his race, whose diet of grain, figs, dates, and dairy products kept them strong and hardy, he would be in good health for many years to come.

It was no accident that Hadjar had acquired a strong influence over the nomadic Tuareg of the Touat and Sahara, who were now confined to the chott region of southern Tunisia. He was as daring as he was intelligent. He had inherited these qualities from his mother, as do all the Tuareg, who trace their ancestry through the maternal line. They regard women as equal, if not superior, to men. In fact, a man whose father was a slave and whose mother was of noble lineage would himself be considered a noble. The opposite never occurs. Djemma’s sons had inherited all her energy, and had remained close to her since the death of her husband twenty years earlier. Under her influence, Hadjar had acquired the qualities of a charismatic leader, with his handsome face, black beard, piercing eyes, and resolute demeanor. At a word from him, the tribes would have crossed the vast expanse of the Djerid, if he had wanted to lead them in a holy war against the foreigners.

In short, he was a man in the prime of life, but he could not have succeeded in escaping without some help from the outside. It would not be enough to pry off the grating and crawl through to the other end of the drain. Hadjar knew the gulf, and he was aware of the powerful currents that build up there, even though, as throughout the whole Mediterranean basin, the tide never rises very high. He knew that no swimmer would be able to make his way against those currents and that he would be carried out to sea without being able to set foot on dry land, either above or below the fort.

There had to be a boat waiting for him at the end of that passage in the corner of the prison wall.

When Harrig had finished giving all this information to his companions, the merchant said simply, “I’ve got a boat over there that you can use.”

“Will you take me to it?” asked Sohar.

“When the time comes.”

“You’ll have kept your part of the bargain, then, and we’ll keep ours,” added Harrig. “If we succeed, we’ll double the sum we promised you.”

“You’ll succeed,” insisted the merchant. Like a typical Levantine, he viewed the entire operation merely as a highly profitable business transaction.1

Sohar got to his feet. “What time is Hadjar expecting us?” he asked.

“Between eleven and midnight,” replied Harrig.

“The boat will be there well before that,” Sohar assured them. “Once my brother is on board, we’ll take him to the marabout, where the horses are ready.”

“At that spot,” the merchant pointed out, “you’ll be in no danger of being seen. You can row right up to the beach. There’ll be no one there until morning.”

“But what about the boat?” asked Horeb.

“All you have to do is pull it up onto the sand, and I’ll come and get it.”

Only one question remained to be settled.

“Which one of us will go and get Hadjar?” asked Ahmet.

“I will,” said Sohar.

“And I’ll go with you,” said the old Tuareg woman.

“No, mother,” Sohar insisted. “It will only take two of us to row the boat to the bordj. If we should meet anyone, your presence might arouse suspicion. You must go to the marabout. Horeb and Ahmet will go with you. Harrig and I will take the boat and bring back my brother.”

Realizing that Sohar was right, Djemma simply asked, “When do we leave?”

“Right now,” he replied. “In half an hour, you will be at the marabout. It will take us less than half an hour to get to the base of the fort with the boat, at the corner of the wall where there’s no danger of being seen. And if my brother doesn’t appear by the time we agreed on, I will try—yes, I will try to go in and get him.”

“Yes, my son, yes. Because if he doesn’t get away tonight, we’ll never see him again—never!”

The time had come. With Horeb and Ahmet leading the way, they went down the narrow road leading to the market. Djemma followed them, hiding in the shadows whenever they came across a group of people. They might have been unlucky enough to meet Sergeant Nicol, and it was crucial that he not recognize her.

After they reached the outskirts of the oasis there would be no more danger, and if they stayed close to the base of the dunes they would not meet a living soul until they came to the marabout.

A little later, Sohar and Harrig left the cabaret. They knew where the bazaar merchant’s boat was located and they preferred that he not go with them. He might be noticed by some passerby walking late at night.

It was now about nine o’clock. Sohar and his friend went back up toward the fort and skirted its southern wall.

The bordj seemed quiet both inside and out. Any noise would have been heard, for the air was still, without a breath of wind. It was also dark, for the sky was covered from one horizon to the other with thick, heavy, motionless clouds.

It was not until they reached the beach that Sohar and Harrig encountered any activity. Fishermen were going by, some returning home with their catch, others going back to their boats to head out into the gulf. Here and there, lights pierced the darkness, criss-crossing in all directions. Half a kilometer away, the cruiser Chanzy made its presence known by its powerful searchlights, which sent out luminous tracks across the surface of the water.

Taking care to avoid the fishermen, the two Tuareg headed for a breakwater under construction at the end of the port.

The merchant’s boat was tied up at the foot of the breakwater. An hour earlier, as planned, Harrig had checked to make sure it was there. There were two oars under the seats, and all they had to do was get on board.

Just as Harrig was about to pull in the grapnel, Sohar put a hand on his arm. Two customs officials, on watch along that part of the shoreline, were coming their way. They might know who the owner of the boat was and be surprised to see Sohar and his comrade taking possession of it. It was better not to arouse suspicion, to keep their project as much in the dark as possible. The customs officials would certainly have asked Sohar what they were doing with a boat that did not belong to them, and since they had no fishing gear they could not have passed themselves off as fishermen.

So they quickly ran back up the beach and crouched against the breakwater, out of sight.

They stayed there a good half hour, and it is not hard to imagine how impatient they felt when they saw that the customs men seemed to be in no hurry to leave. Would they be on duty there all night? No, at last they went on their way.

Sohar walked across the sand, and, as soon as the customs officials had disappeared in the darkness, he called to his friend to join him.

They hauled the boat as far as the beach. Harrig got in first, then Sohar stowed the grapnel in the bow and followed him.

They quickly fitted the two oars into the oarlocks and gently rowed the boat past the pierhead of the breakwater and along the base of the prison wall, where the waters of the gulf lapped against it.

In a quarter of an hour Harrig and Sohar had rounded the corner of the stronghold and stopped directly beneath the opening of the drain through which Hadjar would try to escape.

At that moment the Tuareg chieftain was alone in the cell in which he was to spend his final night. An hour earlier, the prison guard had left him and drawn the heavy bolt, locking the door of the little courtyard adjoining the cell. With the extraordinary patience typical of the Arabs, whose fatalism is combined with complete self-control under all circumstances, Hadjar was waiting for the moment to act. He had heard the Chanzy fire her cannon. He knew the cruiser had arrived and that he would be taken on board the next day, never again to see this region of chotts and sebkha, this land of the Djerid! But his Muslim resignation was combined with the hope that he would succeed in his attempt. He was certain he could escape through that narrow passage, but had his friends been able to get a boat? Would they be waiting for him at the base of the wall?

An hour went by. From time to time Hadjar left his cell, went over to the entrance to the drain, and listened. The sound made by a boat scraping against the wall would have come through to him clearly, but he heard nothing. He returned to his cell, where he remained absolutely still.

Sometimes, fearful that he might be taken aboard the cruiser during the night, Hadjar listened at the door of the little courtyard to see if he could hear the footsteps of a prison guard. Complete silence reigned all around the bordj, broken only occasionally by the footsteps of a sentinel walking on the platform of the fort.

But midnight was approaching, and the arrangement with Harrig had been that by half past eleven Hadjar would have removed the grating and made his way to the end of the passage. If the boat was there, he would get in at once. If it had not arrived, he would wait until the first light of dawn, and then—who knows?—perhaps he would try to swim to freedom, even at the risk of being dragged away by the currents into the Gulf of Gabès. It would be his last and only chance to escape a death sentence.

Hadjar went out to make sure no one was approaching the courtyard. Then, wrapping his clothing tightly around his body, he slipped into the passage.

The passageway was about thirty feet long and just wide enough for a man of average size to squeeze into it. As Hadjar crawled along it, some folds of his clothing caught and were torn on its jagged sides. But slowly and with great effort, he finally reached the grating.

This grating, as mentioned, was in very poor condition. The bars had come loose from the stone, which crumbled at a touch. After five or six good tugs, it gave way. Hadjar set it back against the side of the passageway, and the way was clear.

The Tuareg chieftain had only two more meters to crawl to reach the opening. This was the hardest part of all, since the drain became extremely narrow at the end. He managed to push through, however, and did not need to wait long.

Almost at once, these words came to his ears: “We’re here, Hadjar.”

With one final exertion, Hadjar emerged half way out of the opening, ten feet above the surface of the water.

Harrig and Sohar stood up and reached out to him. But just as they were about to pull him out, they heard footsteps. Their first thought was that the sound had come from the little courtyard, that a guard had been sent to get the prisoner and take him away earlier than planned. Now that the prisoner was gone, the alarm would be sounded in the fort!

Hadjar’s escape

Fortunately, this was not the case. The sound had come from the sentinel, walking on the prison’s parapet. Perhaps the approach of the boat had attracted his attention, but he could not see it from where he was standing. And, in any case, such a small boat would be invisible in the darkness.

However, they needed to be very cautious. Sohar and Harrig waited a few moments, then seized Hadjar by the shoulders, gradually pulled him free, and lowered him into the boat with them.

A strong pull on the oars propelled the boat seaward. Wisely, they decided not to row along the walls of the bordj or along the beach, but rather to proceed up the gulf as far as the marabout. In doing so, they could avoid the little boats that were moving in and out of the port, for the calm night made for good fishing. As they passed the Chanzy on their beam, Hadjar stood up, crossed his arms, and stared for a long time at the cruiser, his eyes full of hatred. Then, without saying a word, he sat down again in the stern of the boat.

Half an hour later they disembarked on the sand and pulled the boat onto dry land. The Tuareg chieftain and his two comrades headed for the marabout, and reached it without incident.

Djemma came to meet her son, took him in her arms, and spoke only one word: “Come!”

Rounding the corner of the marabout, she rejoined Ahmet and Horeb. Three horses were waiting, ready to dash off into the night with their riders. Hadjar quickly swung up into his saddle, and Harrig and Horeb did as well.

“Come,” Djemma had said when she saw her son. Now, with her hand pointing toward the shadowy regions of the Djerid, she again spoke a single word: “Go!”

A moment later, Hadjar, Horeb, and Harrig disappeared into the darkness.2

The old Tuareg woman stayed in the marabout with Sohar until morning. She had ordered Ahmet to return to Gabès. Had her son’s escape been discovered? Was the news already spreading through the oasis? Had the authorities sent out detachments in pursuit of the fugitive? In what direction across the Djerid would they go looking for him? And would the campaign against the Tuareg chieftain and his followers, which had earlier led to his capture, now be resumed?

“Go!” said Djemma.

That was what Djemma desperately wanted to know before starting out toward the chotts region. But Ahmet could learn nothing as he prowled around the outskirts of Gabès. He even went within sight of the bordj, stopping at the bazaar merchant’s house to tell him that the rescue had succeeded—that Hadjar was free at last and was now fleeing across the solitary wastes of the desert.

The merchant had heard no gossip of the escape and, if there had been any, he would certainly have been one of the first to know.

But the first glimmers of dawn would soon light up the eastern horizon of the gulf, and Ahmet did not wish to tarry any longer. It was important for the old woman to leave the marabout before daybreak. She was well known to the authorities and, next to that of her son, her own capture was of highest priority. While it was still dark, Ahmet returned to her and guided her onto the road to the dunes.

The next day, the cruiser sent a launch to the port to pick up the prisoner and take him back to the ship.

When the prison guard opened the door to Hadjar’s cell, all he could report was that the Tuareg chieftain had disappeared. A glance down the drain, from which the grating had been removed, made it only too obvious how the escape had been carried out. Had Hadjar tried to swim to safety? If so, had the current dragged him out into the gulf? Or, rather, did he have accomplices who might have taken him somewhere along the shore in a boat?

There was no way to know for certain. A search of the area near the oasis brought no results. Not a trace of the fugitive, living or dead, was to be found—either on the plains of the Djerid or in the waters of the Gulf of Gabès.