Читать книгу Invasion of the Sea - Jules Verne - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Closing the Circle: Jules Verne’s Invasion of the Sea

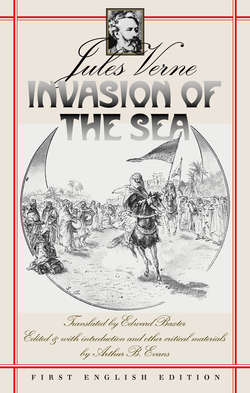

As the first title to be published in Wesleyan University Press’s new book series Early Classics of Science Fiction, this volume of Jules Verne’s Invasion of the Sea is historically significant for many reasons. It is the first English translation of this important work,1 and the first complete, unabridged, and fully illustrated scholarly edition of any late Verne novel ever to appear in print. Its original French counterpart, L’Invasion de la mer, was the last of Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires to be published before the author’s death in 19052 and, as such, the last novel that can be attributed to Verne’s hand alone.3 In many ways, both thematically and narratologically, Invasion of the Sea completes Jules Verne’s fictional odyssey where it began. And it closes the circle on nearly a half-century of “extraordinary” contributions to world literature that, rightly or wrongly, have immortalized him as the “Father of Science Fiction.”4

Publishing History

L’Invasion de la mer (1905, Invasion of the Sea) is one of four late novels by Jules Verne that have previously never been translated into English. The other untranslated titles from Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires—a series comprising over sixty novels published from 1863 to 1919—include Le Superbe Orénoque (1898, The Mighty Orinoco), Les Frères Kip (1902, The Kip Brothers), and Bourses de voyage (1903, Travel Scholarships). Unlike the recent “discovery” of his early unpublished manuscript of Paris au XXe siècle (1994, Paris in the Twentieth Century), these late works by Verne were never “lost.” Following their original French publication in the familiar octavo red-and-gold Hetzel editions, they soon appeared in translation in dozens of other languages, from Spanish to Slovak.5 Yet, to date, they have never been available in English. Why?

The reasons for this perplexing lacuna have less to do with the quality of the novels themselves than with certain trends in the reading and publishing market of the late 1890s and early 1900s. In one sense, Verne was the victim of his own success. With the unparalleled triumph of his early best-selling novels—Cinq semaines en ballon (1863, Five Weeks in a Balloon), Voyage au centre de la terre (1864, Journey to the Center of the Earth), De la terre à la lune and Autour de la lune (1865 and 1870, From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon), Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (1870, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea), and Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1873, Around the World in Eighty Days)—Verne achieved what no writer before him had succeeded in doing: he popularized a new brand of literature that mixed fiction with real science. This new literary genre, a forerunner of what would become known as “scientifiction” and then as “science fiction” in America during the 1920s, might be accurately described as “scientifically didactic Industrial Age epic” or, more simply (as the author himself chose to label it), le roman scientifique—the “scientific novel.” With the worldwide success of his early romans scientifiques, Verne established a strong tradition for this innovative literary form, finally providing it with a socially acceptable institutional “landing point” and ideological model.6 And soon after, spurred on by the public’s increasing interest in contemporary discoveries in science and technology, this new genre became all the rage. During the last years of the nineteenth century, a veritable host of “Verne school” writers such as Paul d’Ivoi, Louis Boussenard, Henry de Graffigny, Georges Le Faure, and Maurice Champagne inundated the French market with their fictional spin-offs. Their immediate popularity—in addition to the growing demand for the speculative works of other French writers such as Camille Flammarion, André Laurie, Villiers de l’Ile-Adam, Capitaine Danrit, Albert Robida, and especially J.-H. Rosny Aîné—soon began to chip away at Verne’s domestic monopoly on these types of narratives.7 Similarly, in Great Britain and America, the English translations of Verne’s oeuvre found itself in competition with imaginative works by a host of anglophone authors such as H. Rider Haggard, Percy Greg, Robert Cromie, James De Mille, George Griffith, Edward Bellamy, Mark Twain, Jack London, and Frank Stockton, as well as with scores of inventive (and cheaply produced) “dime-novels” in series such as The Frank Reade Library.8 Finally, the rapidly growing popularity of Verne’s primary rival, H. G. Wells, had a major impact on the demand for Verne’s fiction.

Undoubtedly, the huge success of H. G. Wells’s “scientific romances” most adversely affected the sales of Verne’s later works, especially among anglophone readers. After the publication of his 1895 and 1898 masterpieces, The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, Wells was promptly acclaimed “the English Jules Verne”9 (i.e., the “new and improved” version). And his highly conjectural fictions soon began to dominate the Anglo-American marketplace. For fin-de-siècle readers at the dawn of a new millennium, Verne’s “hard science” and heavily didactic plots came to be viewed as stodgy and old-fashioned. In contrast, Wells’s scientific romances seemed more imaginative, more cosmic in scope, and more provocative in their futuristic extrapolations. In a word, Verne’s unique and once-successful formula of “scientific fiction” was progressively losing favor to its younger and more fanciful cousin, “science fiction.”10

English-language book publishers during the 1890s and early 1900s were unquestionably aware of and very sensitive to these market trends. Even in France, the demand for Verne’s books had been slowly but inexorably diminishing during the final decade of his life, as he continued to churn out two or three novels per year. In contrast to the continuously sold-out print runs of thirty thousand to fifty thousand copies per title for Verne’s earlier works between 1863 and 1880 (Le Tour du monde en 80 jours alone topped a hundred thousand), the first-edition sales of his later novels, from 1880 to his death in 1905, averaged only seven thousand to ten thousand each. The first printing of Le Superbe Orénoque in 1898, for example, was limited to a mere five thousand—and unsold copies still remained in Hetzel’s stockroom many years later.11 Given these sales trends, it is understandable why British and American publishers might begin to be wary of offering their readers another new English translation of Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires.

But in addition to the factors of decreasing sales and a growing abundance of other Verne-like books in the marketplace, Anglo-American publishers also refused to publish many of Verne’s later works on purely ideological grounds. As described by Vernian scholar Brian Taves:

By 1898, political questions had become the deciding factor in whether the latest Verne books were published in English at all. The tenor of his newer works were less agreeable to English-speaking audiences, or at least their publishers, who were not prepared to faithfully present Verne’s views. The censorship grew beyond simply changing or removing controversial passages until eventually entire books were suppressed by simply not translating them into English. British publishers were fearful of offending their readers in the empire, and the anticipated taste of the British market largely governed what appeared on either side of the Atlantic. Although translations had been appearing with regularity to commercial success for a quarter century, a sudden change in policy was made. The Superb Orinoco became the first of Verne’s annual books not to be translated, and thereafter few of his new works appeared in English.12

As a result, of the seventeen Voyages Extraordinaires published in France after 1898, more than half were destined to remain untranslated into English until the late 1950s and 1960s (in severely abridged editions), and several have remained untranslated until the present day.

The “Two Jules Vernes”

Brief mention should also be made of the quality (or lack thereof) of the early English translations of Verne’s works. It is now recognized that most English-language versions of Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires were very badly translated, and some were so bowdlerized that they bear little resemblance to the original French works. In a rush to bring Verne’s potentially profitable stories to market, British and American translators often severely abridged them by deleting most of the science and the long descriptive passages (sometimes 20 to 40 percent of the original); they committed thousands of translating errors, both literary and technical; they frequently censored Verne’s texts by either removing or “adjusting” passages that might be construed as anti-British or anti-American; and, in many cases, they actually rewrote Verne’s novels to suit their own tastes—changing the names of principal characters, adding new scenes and episodes, reordering or relabeling the chapters, and so forth.

In recent decades, Vernian scholar Walter James Miller has probably done the most to call attention to the shockingly poor quality of some of the English translations of Verne—both in his 1965 introduction to a new translation of Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea and, more importantly, in his two-volume translation series entitled The Annotated Jules Verne (1976–78). Miller’s conclusions are concise and categorical: “The English-speaking world has never had a fair chance to know the real Jules Verne.”13

It is also useful to understand how these English translations were originally published because, at least in Verne’s case, how his novels were published often determined what was published. Verne’s French publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, was a very shrewd businessman and had great success in marketing his books to French readers both young and old. American and British publishers adopted many of Hetzel’s successful strategies but chose to promote Verne’s translations almost exclusively to a juvenile audience. And they did so in one of three ways: elegant, cloth-bound luxury editions that could be offered as holiday gifts, collectible editions such as those in the “Every Boy’s Library” series by the publisher Routledge, or serials in a magazine such as The Boy’s Own Paper (a popular periodical for youth begun in the late 1870s, somewhat reminiscent of Hetzel’s own Magasin d’Education et de Récréation).

Did the editors of the English-language publishing houses purposely shorten, cleanse, and “adapt” Verne’s works in order to better suit this youthful public? Or were the translated manuscripts they received for publication judged to be so unsophisticated in content and tone that only adolescents and preadolescents were targeted as their potential readers? It is impossible to determine. But whatever the sequence of these events, the outcome was the same: Verne’s English translations were marketed primarily to British and American youngsters. As a result, in most anglophone countries until quite recently, Jules Verne’s literary reputation among adult readers has suffered.

But all that is now changing. As I have explained in more detail elsewhere,14 Verne’s critical reappraisal began to gain momentum in France during the structuralist and poststructuralist 1960s and 1970s through the influential studies of both academic and nonacademic scholars such as Michel Butor, Michel Carrouges, Jean Chesneaux, Charles-Noël Martin, Roland Barthes, René Escaich, Michel Foucault, Marcel Moré, Michel Serres, Simone Vierne, and Pierre Macherey. By 1978 (the 150th anniversary of the author’s birth), the literary stature of Jules Verne and his Voyages Extraordinaires had already begun to metamorphose. No longer a paraliterary pariah, Verne was rapidly moving to—as one critic rather hyperbolically mused—“a first-rank position in the history of French literature.”15 And this Verne renaissance has continued through the 1980s and 1990s through the work of Piero Gondolo della Riva, François Raymond, Christian Robin, Olivier Dumas, Jean-Michel Margot, Volker Dehs, Daniel Compère, and Jean-Paul Dekiss.

In America and Great Britain, however, still burdened with the poor English translations described above, a similar reassessment of Verne’s place in literary history has lagged far behind.16 But a glimmer of hope now shows on the horizon. First, new and more accurate English-language versions of a (very) few of Verne’s works have begun to appear in the Anglo-American marketplace during the past few years.17 Second, during the mid- to late 1980s, a handful of American and British university scholars completed their doctoral theses on Verne and subsequently published them as books,18 paving the way for more advanced study of this French author in academe. And, finally, the 1990s witnessed a variety of developments in Great Britain and America that brought Jules Verne out of oblivion and into the limelight: the discovery and publication of his early futuristic dystopia Paris in the Twentieth Century, the birth of the North American Jules Verne Society (along with its informative newsletter Extraordinary Voyages), the online presence of Zvi Har’El’s excellent Jules Verne website (http://JV.Gilead.org.il/), and a growing number of English-language studies on Verne by British and American scholars such as myself, William Butcher, Andrew Martin, Brian Taves, Stephen Michaluk Jr., George Slusser, Herbert Lottman, Ron Miller, Lawrence Lynch, Peggy Teeters, and Thomas Renzi.

In the three and a half decades since Walter James Miller first remarked that two entirely different Jules Vernes seemed to exist in America and in Europe,19 a great deal of progress has been made toward familiarizing anglophone readers with the “real” Jules Verne. But much remains to be done. Of highest priority are first-edition printings of all previously untranslated works by this prolific French author. Next in importance are updated and unabridged editions of those many Verne novels that are currently available only in severely bowdlerized English translations. Finally, there continues to be a pressing need for new collections of translated Vernian criticism in order to provide a critical “bridge” for Anglophone researchers to the wealth of extant foreign-language scholarship on Jules Verne. The first step has now been taken. Wesleyan University Press is to be commended for publishing Verne’s Invasion of the Sea as the inaugural volume in its new Early Classics of Science Fiction series, and additional Verne titles will be forthcoming. It is hoped that these critical editions of Verne’s works will serve both as a catalyst to more English-language studies of this important author and as a stepping-stone to a long overdue reassessment of the place of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires in the evolution of this unique literary genre.

Historical Sources for Invasion of the Sea

It is not unreasonable to assert that the majority of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires were either inspired by or documented from real scientific discoveries, theories, or debates taking place during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Although not a scientist himself, Verne was an indefatigable documentationalist and spent many hours each day keeping abreast of recent developments in the field. For example, during an 1894 interview, he explained:

I have never studied science, though in the course of my reading I have picked up a great many odds and ends which have become useful. I may tell you that I am a great reader, and that I always read pencil in hand. I always carry a notebook about with me, and immediately jot down, like that person in Dickens, anything that interests me or may appear to be of possible use in my books. To give you an idea of my reading, I come here every day after lunch and immediately set to work to read through fifteen different papers, always the same fifteen, and I can tell you that very little in any of them escapes my attention. When I see anything of interest, down it goes. Then I read the reviews, such as the “Revue Bleue,” the “Revue Rose,” the “Revue des Deux Mondes,” “Cosmos,” Tissandier’s “La Nature,” Flammarion’s “L’Astronomie.” I also read through the bulletins of the scientific societies, especially those of the Geographical Society, for, mark, geography is my passion and my study. I have all Reclus’s works—I have a great admiration for Élisée Reclus—and the whole of Arago. I also read and re-read, for I am a most careful reader, the collection known as “Le Tour du Monde,” which is a series of stories of travel. I have thus amassed many thousands of notes on all subjects, and to date, at home, have at least twenty thousand notes which can be turned to advantage in my work, as yet unused.20

It is thus very likely that two reports published in 1874 immediately attracted Verne’s attention. The first appeared in the French Geographical Society’s March Bulletin (for its members) and the second—almost identical in content—was printed in May in the popular journal Revue des Deux Mondes (for the public at large). Written by Captain François-Élie Roudaire, geographer in the French army, both articles proposed “une mer intérieure en Algérie” (an inland sea in Algeria) via the construction of a two-hundred-kilometer Suez-like canal linking the Tunisian Gulf of Gabès with the eastern territories of Algeria. Such a waterway would allow the Mediterranean to fill nearly eight thousand square kilometers of semiarid desert and saltflats (the chotts), which were below sea level and assumed to have once been covered by an ancient inland sea. This artificially engineered body of water, according to Roudaire, would serve many purposes: it would bring moisture and humidity to this Saharan region, dramatically improving its climate; it would permit marine navigation as far west as Biskra (Algeria), thereby facilitating increased commerce with—and colonial influence on—the peoples of North Africa; and it would create a natural barrier against the troublesome desert Tuareg tribes of the south.

Roudaire’s proposal was the result of a geographical and geological survey he had conducted of this area during the previous year. It included specific engineering recommendations for the construction of such a canal, provided details of the various topological obstacles to be overcome, and even suggested an estimated budget (a modest twenty-five million francs). Roudaire’s daring yet pragmatic proposition was strongly supported by the famous French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, and it immediately sparked widespread interest among the French public. In July 1874, the French Academy of Sciences created a commission to study the question. In the same month, the French government unanimously approved a supplement of thirty-five thousand francs to the annual budget of the Committee of Scientific Missions (of the Ministry of Public Instruction) in order to send a military expedition, led by Roudaire, to North Africa to determine the project’s feasibility.

Over the ensuing eight years, Roudaire led several more reconnaissance missions to North Africa, and, with the political and financial backing of de Lesseps, worked tirelessly to materialize his dream of a “Sahara Sea.” But despite being promoted to major and then lieutenant colonel during this period, Roudaire’s ambitious plan was never adopted. By 1882–83, French scientists and politicians had turned against his project. The scientists cited basic geological and hydrometric errors in Roudaire’s reports (e.g., that this region had never contained an inland sea), and the politicians cited both the astronomic cost (over a billion francs) and the enormous social and political ramifications of relocating the indigenous peoples there. Exhausted, embittered, and abandoned by his erstwhile supporters—by this time, de Lesseps was embroiled in his own problems (financial and other) related to his new Panama Canal venture—Roudaire died on January 15, 1885, at age forty-eight, from a fever contracted during his final expedition.21

A sad story. But a quite noteworthy one, not only because Roudaire’s ill-fated project was the primary historical source for Verne’s novel Invasion of the Sea but also because it serves as a concrete example of Verne’s practice of documenting current events and incorporating them in his fiction.22 In fact, Verne’s first novelistic reference to Roudaire’s “Sahara Sea” was not in his 1905 novel Invasion of the Sea but, rather, in an earlier novel—Hector Servadac (1877)—a work whose composition and publication were contemporary with the French engineer’s real-life efforts. Although an interplanetary disaster narrative, the story of Hector Servadac takes place mostly in Algeria and Tunisia, and it contains a revealing passage in chapter 11 and an equally revealing footnote in chapter 13:

The reason that induced the Count and his two colleagues to persevere in their investigations towards the east was that quite recently a long-abandoned project had been revived and, by French influence, the new Sahara Sea had been created. This great achievement, which had refilled the Lake Tritonis that had borne the vessel of the Argonauts, had not only secured to France the monopoly of traffic between Europe and the Soudan, but had materially improved the climate of the country. From the gulf of Cabes [sic] in lat. 34° N., a wide channel had been opened for the purpose of giving the waters of the Mediterranean access to the vast depression which comprehended the Shotts of Kebir and of Gharsa; the isthmus existing between an indentation of the Tritonis basin and the sea having been cut asunder, so that the water had once again taken possession of the ancient bed, whence, in default of a continuous supply, it had long ago evaporated under the influence of the Libyan sun. (Chap. 11)

Map of the Proposed Saharan Sea (Duveyrier, 1875).

1.… England, astonished at the success of the Sahara Sea lately formed by Captain Roudaire, and unwilling to be outdone by France, was occupied in a great scheme for the formation of a similar sea in the centre of Australia. (Footnote in chap. 13)23

In other words, as early as 1876–77, Verne was already assuming the successful completion of this historic “Great Works” project in the not-too-distant future—nearly three decades before he would begin writing Invasion of the Sea (a narrative whose own fictional setting, incidentally, is nearly three decades into the future from its date of composition). Further, the unqualified success of this Sahara Sea, “lately formed” by the French, provided Verne with a handy means to satirize ongoing Franco-British rivalries (also extrapolated into the future), as England immediately set about constructing its own “inland sea” in its colony of Australia.

Thematic and Ideological Significance of Invasion of the Sea

Verne’s Invasion of the Sea is a novel that “closes the circle” on both the author’s life and those Voyages Extraordinaires that were by his hand alone. And it does so in a very fitting manner by returning the reader to the continent of Africa—the fictional locale of Verne’s first novel in this series, Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863). Of course, Invasion is not one of Verne’s best works, especially if compared to some of his recognized masterpieces like Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea or Around the World in Eighty Days. But it is nevertheless a fascinating one because, when viewed from a thematic and ideological standpoint, Invasion of the Sea also “closes the circle” in another important way—it marks the author’s unexpected return to the Hetzel-mandated, optimistic, and pro-science positivism that was evident throughout much of his early writing career.24

Many works in the latter half of the Voyages Extraordinaires, dating roughly from the 1880s, exhibited a growing anti-science pessimism in Verne’s outlook, and issues of human morality and social responsibility tended to be foregrounded more often. Consider, for example, the dystopian portrayal of the “City of Steel” (Stahlstadt) constructed by Verne’s first truly evil scientist, Herr Schultze, in Les Cinq Cents millions de la Bégum (1876, The Begum’s Fortune); or the famous “Gun Club” engineers Barbicane and Maston in Sans dessus dessous (1889, The Purchase of the North Pole), who, as caricatures of their former selves, are wholly indifferent to the potentially catastrophic effects on the entire world when they attempt to alter the earth’s axis with a blast from a gigantic cannon; or, finally, in Maître du monde (1904, Master of the World), the once-heroic aeronaut Robur turned crazed megalomaniac, who, with his powerful vehicle Epouvante, now seeks to rule all the nations of the earth. In these and many later Voyages Extraordinaires, the central “message” of the story seems to echo the dictum of François Rabelais: “Science sans conscience n’est que ruine de l’âme” (science [knowledge] without conscience leads to the ruin of one’s soul). Further, in many of these works, it is only through the last-moment intervention of a providential deus ex machina—in the form of a gas leak, a lightning bolt, etc.—that the heroes are saved, the presumptuous scientist(s) punished, the scientific “novum” eliminated, and the status quo safely reestablished.

In contrast, Verne’s Invasion of the Sea seems astonishingly “politically incorrect” in its near total inattention to the potential human and environmental consequences of constructing an inland sea in North Africa. And the sudden earthquake that functions as the deus ex machina climax of this novel, rather than destroying the project and causing a return to the status quo, actually completes the French scientists’ work-in-progress: the “Sahara Sea” is ultimately created, albeit by natural causes instead of by human design. Finally, suggesting the wrath of a vengeful God, an ensuing tidal wave drowns the rebellious Tuareg and their leader Hadjar, who had fiercely opposed this project from the beginning. The implication is quite clear: both morality and destiny are on the side of Science and Progress.

Although some critics have dismissed Verne’s Invasion of the Sea as merely “one more panegyric to the civilizing mission of the Europeans,”25 its true status within Verne’s oeuvre is considerably more complex. What caused the aging and ailing Verne to suddenly revert to the apparent positivistic ideology of his earliest works? Why, for the first time in his Voyages Extraordinaires, did he abruptly end his narrative after the completion of the scientific project in question, portraying no fictional follow-up to its realization? Why, after so many late novels in which he had sympathetically portrayed numerous oppressed peoples—for example, Greek freedom fighters in L’Archipel en feu (1884, Archipelago on Fire), Hungarian nationalists in Mathias Sandorf (1885, Mathias Sandorf), French-Canadians in Famille-sans-nom (1889, Family without a Name), and Russian peasants in Un Drame en Livonie (1904, A Drama in Livonia)—did Verne apparently turn his back on the fate of the Saharan Tuareg in their fight against French colonialism? And why, instead of A New Sea in the Sahara, did Verne choose at the last moment to retitle this work The Invasion of the Sea—a title that, ironically, would seem to reflect the perspective of the Tuareg themselves as victims of this twofold “invasion”? There are no definitive answers to these important questions, and scholarly opinion on them continues to be divided.26 But one fact is certain: this novel is both more polyvalent and less prone to facile reductionism than any one-dimensional reading of it might suggest. If Jules Verne’s Invasion of the Sea “closes the circle” on his life’s work, critical discussion of the book itself remains far from closed.