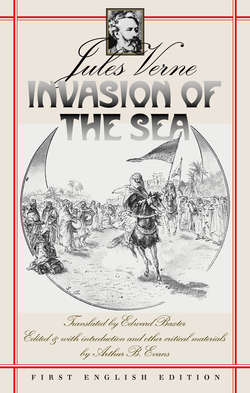

Читать книгу Invasion of the Sea - Jules Verne - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеv The Caravan

As Mr. de Schaller had announced at the meeting in the casino, the work would be resumed in an orderly and energetic fashion after the planned expedition returned, and the Gabès ridge would finally be breached, permitting the waters from the gulf to flow through the new canal. But the first essential step would be to make an on-site investigation of whatever was left of the previous work. The best method to accomplish that seemed to be to follow the route of the first canal through the Djerid to the point where it emptied into Chott Rharsa, and the route of the second from Chott Rharsa to Chott Melrir, through the smaller chotts lying between them, then to travel around Chott Melrir (after making contact with a work party that had been hired at Biskra), and finally to decide on the location of the various ports on the Sahara Sea.

For the exploitation of the two million five hundred thousand hectares granted by the state to the France-Overseas Company,1 as well as the purchase, as needed, of the latter’s existing constructions and available raw materials, a powerful new company had been formed, with a board of directors based in Paris. The stocks and bonds issued by the new company seemed to elicit a favorable response from the public. Their quoted value in the stock exchange was high, mostly because of the financial success the company’s directors had previously shown in large business dealings and beneficial public works projects.

The bright future of this undertaking, one of the largest of the mid-twentieth century, seemed to be guaranteed from every standpoint.

The new company’s chief engineer was the very speaker who had just outlined the history of the work already completed, and he would be in charge of the expedition that would assess the present state of this work.

Mr. de Schaller was forty years old, of medium height, strong-willed (or, to use the popular expression, bull-headed), with short hair, a reddish-blond moustache, a small mouth, thin lips, sharp eyes, and a piercing gaze. His broad shoulders, his strong limbs, the barrel chest where lungs pumped as smoothly as a high-pressure machine in a large, well-ventilated room, were all signs of a very robust constitution. And he was as perfectly well equipped mentally as he was physically. After graduating near the top of his class from Central,2 he immediately made a name for himself with his first construction projects and progressed rapidly along the road to fame and fortune. No one ever had a more positive attitude than he. With his reflective and methodical mind—mathematical, if one may use that term—he never let himself be deceived by illusions. It was said of him that he calculated the chances of success or failure of a situation or a business affair with a precision “carried to the tenth decimal place.” He reduced everything to figures and summed it up in equations. If ever there was a human being immune to flights of fancy, it was certainly this number-and-algebra man, who had been assigned to complete the vast work of creating the Sahara Sea.

Since Mr. de Schaller, after an objective and meticulous study of Captain Roudaire’s plan, had declared it to be feasible, then that clearly meant it was. Under his direction, there would certainly be no miscalculation in either materials or finances. Those who knew the engineer said over and over again, “If de Schaller is involved in the project, it must be a good one!” and there was every reason to assume that they were right.

Mr. de Schaller’s plan had been to travel around the perimeter of the future sea, to make sure nothing would prevent the water from flowing through the first canal as far as the Rharsa and through the second as far as the Melrir, and to check on the condition of the banks and shoreline that would contain the twenty-eight billion tons of water.

Since his team of future coworkers would include some members of the France-Overseas Company as well as new engineers and entrepreneurs, some of whom, including senior officials, could not come to Gabès at that time, the chief engineer had decided not to take with him any members of the new company’s still incomplete personnel, in order to avoid any subsequent conflict of authority.

He did take with him, however, a servant, or valet—if he had not been a civilian, he could have been called an “orderly.” Punctual, methodical, one might say “military,” even though he had not seen military service, Mr. François was the ideal man for this task. His robust health enabled him to endure without complaint the many exhausting ordeals he had experienced during his ten years in the engineer’s employ. He said little, but though he was short on words, he was long on ideas. He was a thinking man, a perfect precision instrument, for whom Mr. de Schaller had a high regard. He was sober, discreet, and clean, and would never let twenty-four hours go by without shaving. He wore neither sideburns nor moustache, and had never, even under the most difficult conditions, neglected his daily toilette.3

It goes without saying that the expedition organized by the chief engineer of the French Sahara Sea Company would not accomplish its objectives unless certain precautions were taken. It would have been foolhardy for Mr. de Schaller to set out across the Djerid accompanied only by his servant. Work sites established by the former company were widely separated and lightly guarded, if at all; accordingly, communications were notoriously unreliable, even for caravans, in this land where nomads were constantly on the move. The few military command posts set up previously had been taken out of service many years ago. Further, the attacks of Hadjar and his band must not be forgotten. That fearsome leader, following his capture and imprisonment, had escaped before the just sentence in store for him could rid the country of his presence. It was only too obvious that he would want to resume his thieving activities.

Moreover, the situation was in Hadjar’s favor at the moment. It was highly unlikely that the Arabs of southern Algeria and Tunisia, to say nothing of the sedentary and nomadic tribes of the Djerid, would stand by without protest while Captain Roudaire’s project was carried out, for it would involve the destruction of several oases in the Rharsa and Melrir regions. The owners would be compensated, of course, but by and large, the compensation would not be to their advantage. Undoubtedly, some interests had been infringed upon, and those owners felt a deep hatred whenever they thought of their fertile touals disappearing beneath the waters coming in from the Gulf of Gabès. Those peoples whose way of life would be disrupted by the new “Sahara Sea” now also included the Tuareg, who were still inclined to resume their adventurous life as caravan raiders. What would become of them when there were no more roads among the chotts and sebkha, when the caravans that had been traveling the desert toward Biskra, Touggourt, or Gabès since time immemorial no longer carried on their commerce? Merchandise would be transported in the region south of the Aurès Mountains by a fleet of schooners and tartans, brigs and three-masters, sailing vessels and steamships, to say nothing of a whole native merchant marine. How could the Tuareg ever dream of attacking them? It would mean imminent ruin for these tribes who lived by piracy and pillage.

The undercurrent of unrest among this particular part of the population was quite understandable. Their imams4 were inciting them to revolt. Several times, Arab workers employed in digging the canal were attacked by angry mobs and had to be protected by calling in Algerian troops.

“What right,” proclaimed the Muslim holy men, “do these foreigners have to turn our oases and plains into a sea? Why do they try to undo what nature has done? Is the Mediterranean not big enough for them, that they must now add our chotts to it as well? Let the Frenchmen sail around on it as much as they like, if that makes them happy, but we are land dwellers, and the Djerid is meant to be traveled by caravans, not by ships. These foreigners must be wiped out before they drown our land, the land of our forefathers, under the invading sea!”

This growing agitation had played a part in the downfall of the France-Overseas Company. Over time, after the work was abandoned, it had seemed to subside, but the inhabitants of the Djerid were still haunted by the fear that the desert might be invaded by the sea. This fear had been consistently encouraged by the Tuareg ever since they had settled south of the Arad, and by the hajjis, or pilgrims, returning from Mecca, who maintained that their brethren in Egypt had lost their independence with the building of the Suez Canal. It continued to be a universal concern, one that was uncharacteristic of Muslim fatalism. These abandoned installations, with their fantastic equipment—enormous dredges with strange levers that looked like monstrous arms, excavators that might well be compared to gigantic land octopuses—had entered into local legend and figured prominently in the tales told by the country’s yarn-spinners, tales that those people have eagerly listened to ever since the Arabian Nights and the other narratives of countless Arabian, Persian, and Turkish storytellers.

By reviving memories of people of ancient times, these stories kept the native population obsessed with the idea of an invasion by the sea. It is not surprising, then, that Hadjar and his followers had, prior to his arrest, been frequently involved in aggressive actions against this project.

For this reason, the engineer’s expedition would be carried out under the protection of an escort of spahis led by Captain Hardigan and Lieutenant Villette. It would have been difficult to find better officers than these two, since they were familiar with the south and had successfully led the difficult campaign against Hadjar and his band. They would study what security measures needed be taken to protect the project’s future.

Captain Hardigan was in the prime of life, barely thirty-two years old, intelligent, daring but not rash, accustomed to the rigors of the African climate, and possessed of a stamina that he had demonstrated beyond question during his many campaigns. He was an officer in the fullest sense of the term, a soldier at heart, who could see no other career in the world than the army. Since he was a bachelor and had no close relatives, his regiment was his only family, and his comrades-in-arms were his brothers. He was not only respected in the regiment, but loved. The affection and gratitude of his men showed in their devotion to him, and they would have sacrificed their lives for him. He could expect anything from them, and could ask anything of them.