Читать книгу Jesus Land - Julia Scheeres - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

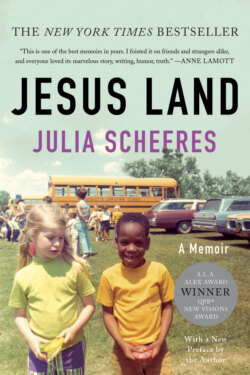

When we were kids, my brother David and I hunted box turtles in the woods of our small Indiana town. We played hours of Monopoly and War in our blanket fort under the Ping-Pong table. We crossed the frozen Wabash, gripping hands as the ice fissured beneath our moon boots. We traded silly faces during tedious Sunday sermons, summer beckoning through the stained-glass windows.

And we encouraged each other with a single word: “Florida.” When we were in fifth grade, our family began vacationing in the Sunshine State, and it was there that we stumbled upon a kind of utopia: kids of every color forming fast friendships around the kidney-shaped pool. Back in Indiana, David and I were often marginalized because our family was different: my white parents adopted David, an African American, when we were both three years old. At the neighborhood pool, a gang of siblings once jumped us as we left the locker rooms, angered that we had “polluted” the water. But in Florida, skin color felt as inconsequential as eye or hair color. What mattered was fun, your ability to spout Michael Jackson trivia, the size of your cannonball off the stiff tongue of the diving board.

In Florida, our minds were opened. There were other ways of being. “Florida” became our password for hope, symbolic of an Eden we’d enter after crossing that magical threshold into adulthood. “Remember Florida,” I told David after a redneck kicked him in the crotch on the first day of high school. “Remember Florida,” he’d say when I ate lunch locked in a toilet stall to avoid bigots in the cafeteria. David would crack a corny joke or persuade me to go on a bike ride, and soon we’d be laughing, feeling powerful, feeling, in advance, the freedom that would someday be ours.

We were still mulling over Florida at age twenty, when I was a college sophomore in Michigan and Dave enlisted in the Indiana National Guard. His lot was starting to improve. He bought a secondhand Plymouth Turismo—black with red racing stripes—and on August 1, 1987, he was driving over to show it off to me when he lost control on a gravel country road and slammed into an oak tree.

He died four miles from our childhood home, and nine hundred miles away from Florida.

A part of me died that day, too—the hopeful part. The unfairness of his death, coming just as his life was becoming what he wanted it to be, astounded me. It enraged me. I spent the next two years of college haunting the municipal library and eating from vending machines so I didn’t have to interact with those ebullient, carefree college kids. How I resented their unstained hearts and unclouded futures. My anguish morphed into physical pain: chronic migraines, heartburn I tried to quell with peach schnapps. I no longer had David to counterbalance my tendency toward gloom. He’d always believed that life could—would—only get better. He had been wrong.

After graduating with a BA in Spanish, I flew to Spain, vowing never to return to the United States. Overseas, I tried to forge a new identity. When asked about my family, I’d talk about my other siblings, never mentioning David. I distracted myself with men and dancing and remote sunbaked villages. I fell in love, and then that love fell apart, and I was forced to return to the States.

I enrolled in graduate school to become a journalist; I wanted to focus on other people’s lives instead of my own. And with time, I let David come back to me: in my memory, in my writing. I remembered his ability to make me laugh with his silliness and the feeling of security he gave me, the way he always had my back.

I never did move to Florida. I chose somewhere more progressive and diverse: California. Today, as I walk down the street here past people of every color, I deeply regret that Dave didn’t make it this far. After all these years, the fact of his death is still a sucker punch to the heart. But then I look down at the hand nestled in mine which belongs to my nine-year-old daughter, Davia Joy—my brother’s namesake. Davia celebrates her birthday one day after her uncle’s and sleeps with his stuffed Snoopy in the crook of her arm. They even share a nickname: Dave. Davia cherishes stories about her Uncle David. I relish telling them. Whenever I say “I love you, Dave,” I’m telling both of them.

Because love, I’ve learned, doesn’t end with death. It lives on. Even if it’s painful to remember, we must. Once I let myself think of David after years of running from the sadness of his loss, I felt a small measure of relief. Now I simply accept my grief—as part of the beauty and devastation that pulse, side by side, through every life.

2018