Читать книгу Jesus Land - Julia Scheeres - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

FRIENDS & NEIGHBORS

David’s in okra and I’m in snow peas. We kneel in parallel rows killing Japanese beetles as the sun bores down on us. We each have different methods of doing this. David plucks the beetles off the leaves with gloved fingers, squeezes them until they pop, then tosses them over his shoulder. I find this repulsive. The ground behind him is littered with their mangled metallic green and copper bodies. My method is to bat them off the plants with a trowel, then press them into the dirt with the blade, where I won’t see their insides squirt out. Sometimes I whack off leaves or vegetables in the process, but at least I don’t see the beetles die. Secretly, I think they’re beautiful.

I pause to swipe my dripping forehead with the back of my arm and look up at the house. A grackle squawks overhead and lands on the clothesline, its purple-black body gleaming in the sun like spilled motor oil. At the end of the driveway, our mutt Lecka lies panting in the shade of her doghouse. Her name means “sweet” in Dutch. Our family tree reaches back to Holland on both parents’ sides, and we attend a Dutch Calvinist church in town where people slap bumper stickers on their cars that proclaim “If you’re not Dutch, you’re not much.” Until this year, we attended a Dutch Calvinist school as well, where all the kids were blond and lanky like me—all the kids except Jerome and David, of course.

Through the dark glass of the upstairs window, I can just make out Mother sitting in the recliner, feet up, a glass in one hand, a Russian-language book in the other. The ceiling fan spins lazily above her. She’s learning Russian because the Communists are persecuting Christians, and there’s a great need for people to smuggle Bibles behind the Iron Curtain to these clandestine congregations. She wants to be prepared should the Lord call her on that mission.

“What if the Commies catch you?” I recently asked her, although I already knew her answer: The best thing you can do in life is die for Jesus Christ.

But I’m not too scared of her being martyred. According to the page marked in her textbook, Take Off in Russian, she’s still learning to ask directions to the toilet and say “I prefer cream in my coffee.” She’s got a long way to go before she can pass herself off as a babushka.

The telephone jingles as I start down a row of cauliflower, and I look up to see Mother rise to answer it, disappearing into the shadows where light from the great room windows doesn’t reach.

Our new house is what they call “ranch style.” There are three bedrooms upstairs—the master suite, my room, a guest room—and one in the basement for the boys. They share it, just like they did in the basement of our old house.

The entire house, bathrooms included, is wired with an intercom system, and every morning at eight Mother blares Rejoice Radio over the speakers to wake us up. It took a while to get used to this. At first I would jackknife awake, panicked that I’d fallen asleep in church. Now when the organ music starts, I thrust my pillow over my head and try to refill my ears with the sweet syrup of sleep until Mother comes pounding on the door.

“Idle hands are the devil’s workshop!” she’ll call through the wood. It’s her favorite saying, along with “Cleanliness is next to Godliness” and “Honor thy father and thy mother.”

The intercom has another important function: spying. Control panels in the kitchen and master bedroom have a black switch that can be flipped to “listen” or “talk.” You can tell when Mother’s eavesdropping because the speakers crackle, but we can’t turn the volume down or off because we get in trouble if we don’t hear her call us.

When David and I need to speak privately, we go outside. We spend most of our time there anyway. Mother’s got romantic notions about toiling the land—or mostly, about her children toiling the land. And with fifteen acres, there’s always something that needs toiling with.

The garden gets the thrust of our attentions. We try to get at it early, before the vegetation perspires in the heat, sending up a dizzying haze that can sting your eyes. We work on our hands and knees, ripping out crabgrass and pennyworts, killing Japanese beetles and cabbage loopers, aerating and fertilizing, all the while swatting at the horse flies and sweat bees that buzz around us.

Although we complain about our chores, there is a satisfaction to poking an itty-bitty tomato seed into the dirt and watching it resurrect and snake into a six-foot vine. David and I take a certain pride in our work, marveling at the two-foot zucchinis and the baskets of ruby red strawberries our hands help produce. Our garden is so bountiful that Mother fills grocery sacks with the surplus to bring to the soup kitchen downtown.

“I bet there’s no Japanese beetles in Florida!” David says, pitching a crushed bug over his shoulder; it lands in the pink and orange zinnias bordering the garden.

“Nope, only geckos.” I pinch off a snow pea and bite through the shell into the sweet green balls inside. “And jellyfish.”

Florida! That’s where David and I are moving when we turn eighteen. Things are different in Florida. Until three years ago, our family drove there every August to a timeshare condo on Sanibel Island. David and I would spend the week running around barefoot and unsupervised. There was a group of secular kids at the complex who hung out with us despite our skin color. Florida’s the place where I first got drunk, first made out with a boy, first got my heart ripped to shreds.

Did it all on our last trip with Alex Garcia, a seventeen-year-old local who lounged around the complex pool in tight white bathing trunks. We flirted all week, and the night before we left, he convinced me to meet him on the beach at midnight. I wore my clothes to bed—carefully pulling the sheet around my neck so my older sister Laura wouldn’t notice—and watched the alarm clock for two hours, my heart racing. When I slipped out to our designated meeting place, Alex held beer cans to my thirteen-year-old face until I passed out. When I came to, he was lying on top of me, his tongue rammed down my throat. I pushed him off and ran away.

“You’re so immature!” he yelled after me.

The next morning I woke with bruises circling my mouth, but despite this, I loved Alex. He was beautiful with his caramel skin and those white trunks. But as we were driving out of the complex to return home, I saw him by the pool, frenching a twenty-two-year-old who’d just arrived that morning. I cried all the way back to Indiana.

“Too bad Jerome screwed everything up for us,” David says, rocking back on his haunches and scowling at me over the broccoli. His glasses are powdered with dust.

“Yeah, we’d be there right now if it weren’t for him,” I say, popping another snow pea into my mouth. I wonder who Alex is kissing this summer.

“I can’t believe Jerome was so dumb,” David says. “I mean, our parents aren’t completely dense.”

I nod and wave away a sweat bee that’s trying to land on my face. Our parents put an end to Florida when Jerome showed up one evening reeking of beer, too drunk to remember to gargle and spray himself with Glade. David doesn’t know what I did with Alex. No one does; it’s my secret, one that both shames and thrills me.

A bead of sweat runs down the back of my neck and I glance at my watch. It’s two o’clock, just about peak heat time, and we still have to do the squash, the beans, the carrots. An hour ago, the back door thermometer was already pushing ninety-three degrees, and that was under the eaves. The sky is covered with a low cloud quilt, the sun reduced to a white pinhole. It’s the usual, year-round Indiana sky, always a pearly glare. Sometimes the heat and humidity are so intense that the quarter-mile walk down the lane to check the mailbox seems like an epic journey through hot Jell-O.

“I need a drink,” I say, lurching up on legs bloodless and wobbly from being bent. I look at the upstairs window; the recliner’s still empty. She must be in the study, corresponding with her missionaries, scribbling churchy news onto onion paper in her loopy cursive. I peeked at some of her letters last week when she went into town for groceries; they were “I need a drink,” I say, lurching up on legs bloodless and wobbly from being bent. I look at the upstairs window; the recliner’s still empty. She must be in the study, corresponding with her missionaries, scribbling churchy news onto onion paper in her loopy cursive. I peeked at some of her letters last week when she went into town for groceries; they were tucked into unsealed envelopes destined to countries around the world.

We took a collection to renovate the narthex. Lord willing, we’ll have enough for new carpeting and new paint as well. The Grounds Committee hasn’t decided whether the best paint color would be pale blue or eggshell. . . . The Ladies Aide Society is holding a potluck next week before Vespers to welcome new church members. We will open our arms to receive them even as Jesus opens his arms to the sinners and the fallen. . . . Please join us in prayer for President Reagan as he leads the country toward The Light. We are blessed to have a Christian leader in the White House, and must support his efforts to reinstate school prayer and overturn abortion “rights.” . . . In HIS name, Mrs. Jacob W. Scheeres.

“Hey, space cadet!”

David rubs a glove over his gleaming forehead, leaving a chalky smear.

“What?”

“I said, what are you going to be in Florida?”

“I dunno,” I shrug, reaching over to the next row to pull a slender carrot from the dirt and toss it into my basket. It’s best to harvest vegetables while they’re young and sweet, Mother says. “Maybe I’ll make jewelry from shells and sell it on the beach. You?”

“Haven’t figured it out, yet. But it’d be way cool to work on one of those deep-sea fishing boats—I could put a pole in myself, and we’d eat fresh fish every night—grouper, snapper, maybe even shark!”

I scowl at him.

“You’d reek of fish guts. I’d have to hose you down with Lysol every night when you got home.”

As he contemplates this thought, frowning, I walk to the pipe jutting from the ground in the middle of the garden and twist open the faucet. After a couple of burps, the water flows into the attached green hose. I grip the end in my fist, letting the water gurgle over my hand like a fountain, and hold it up to my mouth. It’s well water, warm and weedy-tasting. It thuds into the dust at my bare feet, splattering my legs with muddy droplets.

“Want some?” I hold out my arm to David.

He stands and trudges over. When his face is a few inches from my hand, I slip my thumb over the hose tip and the water jets upward, bouncing off his nose and glasses. It’s an old trick.

“Hey!!”

He reels away and I drop the hose and hurdle rows of vegetables. Before I reach the garden’s edge, water pounds my back. I swerve to dodge the spray while David charges after me. He runs the length of the rubber hose and snaps backward like a yo-yo, falling onto the potatoes, hose still in hand. Water rains down on him, sparkling like shredded sunlight, and I flop belly-down in warm grass, laughing.

Our play is interrupted by a sharp rapping of knuckles on glass, and we look up at the house. A faint figure stands behind the upstairs window, hands on hips. Mother.

After the bone yard incident, David and I stay close to home; we’re not in a hurry to cross paths with the farmers again. We don’t discuss it, we just don’t turn right on County Road 50. We stay out of the deep country.

Jerome returned the Corolla one night while everyone was asleep—probably fearing our parents would report it stolen and sic the cops on him—and then took off again. Mother says we can’t use the car for “frivolous driving,” though, which, in her mind, is all the driving we want to do.

So we’ve spent most of these last few weeks before school playing H-O-R-S-E and P-I-G on the small basketball court next to the pole barn; hiking through the nearby woods and cornfields with Lecka, hoping to stir up pheasants or deer or box turtles; taking turns dangling a bamboo rod rigged with bologna over a fishing hole at the back of our property; playing foosball and ping-pong in the basement. Anything to relieve the boredom and unease that constantly gnaw at us.

But all we catch is junk fish in the fishing hole, slimy carp that are too small to eat. David yanks the hook from their bloody mouths to toss them back into the water as I scream at him not to hurt them. The only thing we’ve kicked up during our hikes was a dead raccoon. And it’s way too hot for sports.

Sometimes we lie on lawn chairs in the backyard in the late afternoon and watch thunderheads churn toward us. We’ll see a breeze riffle the Browns’ cornfield across the lane and lift our faces expectantly to the cool, metal-smelling air and we’ll know we’re in for a good squall. We’ll stay reclined in our chairs as the dark clouds seethe and flicker with lightning, until the cold hard raindrops pelt us, competing to see who can withstand the storm the longest before sprinting under the eaves.

But those are the exciting afternoons. Most times, it’s a devil wind riffling the Browns’ cornfield, and it blasts over us like a hair dryer, pelting us with the smell of dirt and onion grass and manure, and offering no refreshment at all. But we stubbornly remain in our lawn chairs as the overcast sky fades into deeper shades of gray and Mother finally rings the supper bell, because there’s nothing better to do.

As we watch the sky, we talk about things that would make country living easier. For David, that would be a BMX bike. He says he could build a ramp behind the garden and do all these tricks where you flip upside down and land perfectly centered on the fat rubber tires. Says he’s seen it done in magazines. Me, I’d get a horse. A golden palomino that I’d ride bareback through the fields, all the way back to town.

Sometimes we discuss Harrison.

“Do you think all the kids will be like those farm boys?” David will ask, his eyebrows creasing with worry.

“Nah, they can’t all be that ignorant,” I’ll respond. “Some of them have got to be normal.”

Usually he lets it go at that, sitting back in his lawn chair with a sigh, but sometimes he persists.

“But what if they are all like that?” David asks one afternoon as we watch the darkening sky. “Ronnie Wiersma told me they hate black people at Harrison and call them names, you know, like the ‘N’ word.”

Ronnie is a know-it-all at our church, Lafayette Christian Reformed. He went to Lafayette Christian School too, same as all the church kids do, and graduated two grades ahead of us.

“What does Ronnie know? He’s at West Side.”

“His older brother went to Harrison.”

“Yeah, but that was a long time ago, like three years.”

The subject of Harrison always puts me in a foul mood. School starts in a week, and we still don’t have any friends, or any answers to our question. What will it be like? I try to reassure David that everything will be okay.

“Those farmers were just being stupid that day,” I tell him. “We caught them off-guard is all. Now that they know who we are, they won’t bother us.”

All I can do is hope this is true. We often hear them in the distance as we garden: the whine of their dirt bikes banging over homemade tracks, the blare of their car radios as they tear between cornfields, the explosions of their guns as they shoot cans or grackles or squirrels, silencing the world for a long moment afterward.

Jerome, David, and I walk into Harrison on the first day of school sporting matching Afros that envelop our heads like giant black cotton balls. As we stride down the entrance corridor bobbing and grinning like J.J. on Good Times, our classmates recoil in horror.

No.

This will not happen.

This is a nightmare.

I will myself awake and stare at the wind-up alarm clock on the bedside stand. It’s almost six. I stare at it until the black minute hand jerks over the red alarm hand and the clock rattles to life, jittering over the wood surface. I wait until the nightmare dissipates completely, then I slap it quiet.

It’s the Tuesday before classes start and swim team tryouts are in thirty minutes; the coach wants to make sure people can handle the early-morning workouts once school starts. I figure it might be a good way to meet potential friends.

I hear Mother rumbling around in the kitchen, opening and closing drawers and cupboards, but by the time I walk into the great room, pulling my hair into a tight pony tail, she’s gone. I stand at the kitchen counter, gulping down coffee and generic granola doused with powdered milk. The sky is pink outside the great room windows, the orchard and garden wrapped in pink mist.

It’s a mile and a half to Harrison, a right on County Road 650 and a left on County Road 50. I had Mother measure it with the van’s odometer last Sunday after church.

After brushing my teeth, I wheel my ten-speed from the garage onto the gravel driveway. Lecka hears me and crawls from her doghouse, yawning and batting her tail in furious circles. She strains against her collar, whining, and I walk my bike over to her.

“Wish me luck, girl,” I say, tugging on her ears.

As I turn to mount my bike, the venetian blinds in the master bedroom window clap shut. Mother?

I shrug and mount the bike, standing on the pedals to force the Schwinn’s tires over the slippery gravel lane until I reach County Road 650. As I cruise by the Browns’ white clapboard house, a dog barks in the dark interior. Opposite the Browns’, a red barn slowly collapses into overgrown weeds. Next to it, a pair of meadowlarks trill in a sugar maple. Then there’s an alfalfa field, bright with yellow blossoms. I inhale the sweet air and am seized by a sudden joy at the beauty around me. It’s still early, and life hasn’t acquired its sharp edges.

The road dips over a small creek before passing a double-wide trailer mounted on railroad ties. Pink gingham curtains hang daintily in the windows, and the muted voice of a news announcer floats through the ripped screen door along with the smell of percolating coffee.

At the intersection of County Road 650 and County Road 50 is a small brick building where farmers met in the days before telephones to discuss business. I turn left onto the ragged asphalt ribbon of County Road 50, which bisects cornfields and dairies until it reaches town, ten miles away. As I pedal up a small rise, the concrete expanse of William Henry Harrison High School swoops into view, sprouting mushroom-like between fields.

My early-morning joy slams into stomach-grinding fear. I glance at my watch—6:25—before shifting my bike into tenth gear and crouching low behind the handlebars, racing toward my new school. Bring it on.

As I ride closer, I notice tire tracks have ripped donuts into the front lawn. Across from the school, a cow barn is covered in graffiti. “HARRISON KICKS ASS!” “RAIDERS ROCK!” “WESTSIDE IS CRUISIN’ FOR A BRUISIN’!” West Side. That’s where our three older siblings went to school; it’s Lafayette’s smart high school, where the Purdue professors send their kids.

I swerve into the driveway and pedal to the back of the building, remembering the location of the gym from our orientation tour. There they are, about twenty girls, clumped around the back door, bags dumped at their feet. A few sit on the curb, smoking. They look up at me with sullen faces when I coast into view. I am relieved that this look is common to all teenage girls and not just me, as Mother believes.

“What’s wrong with you?” she’ll ask, scowling. “Why don’t you smile more?”

She’s one to talk.

The bike racks are located across from the gym entrance, and as I unwind my bike chain from under the seat, I sneak peeks at the girls. A couple of the smokers I’ve seen before, a fat girl with blond pigtails and a girl in a Tab Cola shirt.

The day after we moved in, Jerome, David, and I were so bored that we rode five miles along the shoulder of Highway 65 to a Kwik Mart. A group of girls, stuffed into cut-offs and tube tops, their eyes raccoonish with black eyeliner, were leaning against the shaded wall of the cement shack. They sucked on popsicles and cigarettes and jutted out their hips at the trucks and jacked-up Camaros that pulled in for gas.

They tittered when we glided into the station, panting and sweat-stained. It was a scorcher, one of those days where the heat feels likely to peel your skin right off. Jerome stopped beside the gas pumps and gawked at the girls while David and I propped our bikes against the building.

“Better watch out, Rose Marie,” one of them shouted. “I think he likes you.”

Rose Marie twisted her dirty blond pigtail around a finger, staring at Jerome and sliding her grape popsicle in and out of her mouth real slow. Her friends squawked with laughter, then poked their fingers in their mouths and made gagging noises.

Jerome grinned at Rose Marie and tucked his fists under his biceps to make the muscles pop out, Totally Clueless. Seeing this exchange, I ran into the Kwik Mart and bought an orange push-up before racing away on my bike. I didn’t want to be seen with the boys at that moment.

“What’d you take off for?” David asked when he caught up to me, an ice cream sandwich melting in his hand. Jerome was farther behind him.

“The smell of gasoline makes me sick,” I lied.

After threading the bike chain between the front tire and the rack, I click the combination lock shut and stand to face the crowd.

Dozens of eyes land on my face, then slide away. It’s a small community. They know who I am. I’m the girl from that new family, the one with the blacks. Sure enough, Rose Marie elbows the Tab girl and they both stare at me, smirking. I unzip my backpack and pretend to dig around in it for something important as I cut a wide circle around them.

There’s a girl sitting alone against the wall and I walk in her direction. She’s dark-haired and olive-skinned, blatantly foreign to these parts as well. We belong together, she and I; we’re both outsiders. She watches me approach, but looks away when I stop and lean against the wall a few feet away from her.

I look at my watch. 6:37.

“So the coach is late?” I ask, trying to sound casual as I zip my backpack closed.

“Seems that way,” she says without looking at me. She plucks a dandelion from the ground and flicks its head off between her index finger and thumb. Mary had a baby and its head popped off . . . Her shoulder-length black hair is feathered about her face, Farrah Fawcett–style, just like mine and every other girl’s here.

“You nervous?” I ask, a bit loudly.

She shrugs.

Across the road, a row of cows plods single file toward the graffitied barn. “EAT, SHIT, AND DIE!” someone wrote over the wide entrance.

“So, what’s your name?” I ask her, sitting in the grass. Talk to me, please. Finally she looks at me, her black bangs skimming her dark eyes like a frayed curtain.

She says something in a foreign language.

“What?”

“You can call me Mary.”

“What country are you from?”

“Arcana,” she says.

“Where’s that at?”

“’Bout two hours east of here.”

“Oh,” I laugh, embarrassed. “I’m Julia. Guess we’re both new.”

She nods, and plucks another dandelion from the ground.

Squeals pierce the air and we turn to watch a group of girls surging around a boy who’s standing over a bicycle, across from the gym entrance. He’s shirtless despite the chill air, wearing only light blue satin running shorts. He thrusts out his chest—tan, broad—and a few of the girls grope it as he laughs.

They scatter when a black Camaro roars into the parking lot. It screeches to a stop slantways across two spaces, and a man in aviator sunglasses jumps out.

“There he is,” Mary says. “Coach Shultz.”

The shirtless boy pedals away, and we stand and move toward the other girls. Coach Schultz comes at us with swooping arms.

“Everyone inside! We’re late!”

“No, you are,” someone mutters.

He jingles a key into the door and holds it open, sizing up bodies as they flow into the building. I thrust back my shoulders as I walk by him, hoping to make a good impression.

In the dank locker room, Mary and I migrate silently to a corner. I try to keep my eyes to myself as I quickly strip off my shorts and T-shirt and snap into my Speedo, but can’t help but notice when the big-chested girl next to me unhooks her bra and her boobs fall down like half-filled water balloons. My own boobs are still little-girl pointy—I’m what people call a “late bloomer.” At sixteen and a half, I haven’t gotten my period yet and am still cursed with a boyish, narrow-hipped body.

The door cracks open and there’s a whistle blast.

“Enough lollygagging, girls!”

Coach Schultz orders us to pair up for warm-up exercises, and everyone immediately nabs a partner, leaving Mary and me for each other. I walk over to her. We do ten minutes of stretching on the tile floor next to the pool, and then the real competition begins.

The coach has us swim fifty yards, freestyle. Some of the girls claw through the water like cats, barely reaching the halfway flag before wheezing to a stop. Coach Schultz orders them out of the pool, and among them I see Rose Marie, sucking in air through her smoker’s mouth and coughing. I grin; the process of elimination has begun.

When my turn comes, I knife through water, happy to deafen the murmuring around me. Twelve strokes to the deep end, flip turn at the black T painted on the bottom, twelve strokes back. This is one thing I do well.

David and I learned to swim at the YMCA when we were six. After I learned to float, my favorite thing to do was to scissor my arms and legs into the middle of the deep end while the other kids huddled at the ledge, terrified of letting go of the tile lip.

“Come back!” David would squeal, twisting his head around to look at me with huge eyes. “Don’t go there!” But the feeling of being alone and hard to reach enthralled me, and I went from polliwog to shark in record time.

Coach Schultz blows his whistle and orders the girls who made the first cut to do continuous laps, alternating between breaststroke, backstroke, and the crawl. I lick the fog from my goggles and press them back to my face, pushing them against my cheekbones until they suck lightly on my eyeballs. At the end of my eighteenth lap, I notice a forest of legs in a corner of the pool. There’s a whistle burst and I rise to the surface along with a handful of other girls, including Mary.

“There’s my A-team, right there,” Coach Schultz shouts, leaning against the lifeguard tower with a clipboard. We call our names to him, and he writes them down.

In the locker room, everyone hustles back into their clothes in hunched silence. I exchange a smile with Mary and pull my shorts over my suit before fleeing the sour gloom, fearing that one mean look will puncture my high spirits. As I bike back up County Road 50 in the swelling heat, carloads of girls with wet hair pass me. Sweat trickles down my face and pastes my Speedo to my body, but I’m elated. I’ve made the swim team and found a friend.

We go to Kmart for our annual trek to buy school clothes, and I hole up in a dressing room with a mound of clothes, hoping to find something that doesn’t look like it was bought at Kmart. This is tricky. I choose a few pastel oxfords and polo shirts—although these have swan icons instead of the trendy alligators and horses—and a pair of plastic penny loafers. A pair of fitted paint-splattered jeans gets nixed by Mother when I walk out to model them for her.

“What do you want people staring at your butt crack for?” she asks loudly, causing several shoppers to turn in our direction. She walks to a rack of dark denim, grabs two pairs of baggy jeans and throws them into our cart as I look away, tears stinging my eyes.

None of the kids I know would be caught dead in the Kmart parking lot, but Mother views blue-light specials as manna from Heaven. Polyester slacks, two pairs for $10? We can outfit the entire family! Reduced-for-quick-sale toothpaste? We’ll stock up for the next five years! Our family shops at Kmart for the same reason we drink instant milk and eat Garbage Soup and use dish detergent for bubble bath: We’re cheap.

Mother still hasn’t gotten over the Great Depression. I know that if I complain about my school clothes, I’ll be subjected to stories about how her family was forced to eat withered apples from her father’s general store in Corsica, and how she left for college with only two flour sack dresses to her name. Shame on you! You don’t know how good you have it! I’d just as soon stick my hand in a vat of boiling oil than hear it once more.

Mother says money we save by being frugal helps the cause of missionaries around the world, but it certainly doesn’t help mine. Once again, I’ll be Dorky Girl at school. My only hope is to find more baby-sitting jobs, so I can acquire enough money to go shopping at Tippecanoe Mall like a normal person.

In the men’s department, David greets us cradling an armload of satin basketball jerseys emblazoned with Big Ten logos. Purdue. Michigan. Notre Dame.

He looks at Mother with a wide-eyed mixture of hope and apprehension, and she shakes her head and strides to a table piled with T-shirts. Colored Hanes, $2.99! Mother scoops several into the shopping cart.

David hugs the shimmering jerseys to his chest.

“What’s wrong with these?” he asks, alarm rising in his face.

I look at him and roll my eyes.

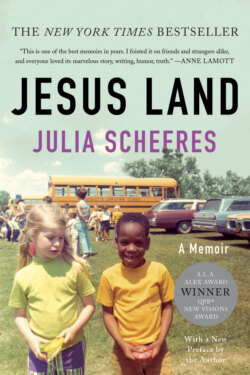

I was three years old when my mother told me I was getting a baby brother.

When she said “your baby brother,” I assumed he’d be mine and mine alone, and swelled with self-importance. I would no longer be the baby of the family; I, too, would have someone to boss around.

A crib was placed in an upstairs bedroom and I’d check it several times a day, peering between the slats to see if my baby had arrived. Time after time, I was heartbroken by the empty mattress.

“Baby here today?” I’d ask Mother.

“Soon,” was always the reply.

The day he arrived, on March 17, 1970, I was in the basement, lost in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood; the older kids were at school. After the show ended, I went to the kitchen for a butter-and-sugar sandwich and Mother hushed me. My baby brother was sleeping, she said, and I was not to disturb him.

I waited until she started washing the dishes before creeping upstairs on my hands and knees. The door to his room was closed, and I paused on the threshold, listening to pots banging against the sink, before pushing the door inward.

The sun streamed through yellow curtains as I approached the crib on tiptoes, breathing hard. Finally. Inside it was my baby doll, asleep. I stared in awe at his molasses-colored skin; nobody told me that my baby would be brown.

I pressed my face between the slats and marveled at him, at the chalky trails of dried tears crisscrossing his face, at his size. He looked much smaller than I was, although he was only four months younger.

He was my baby, and I had to touch him. I reached between the slats and poked his arm with a finger. Too hard. His eyes flipped open, big and brown and watery scared, and I snatched my hand back. His bottom lip started to quiver.

“Shh, baby, shh,” I whispered. “Don’t cry.”

I glanced behind me at the open door; Mother would paddle me if she caught me disobeying.

But my baby didn’t make a noise, he just watched me with those big brown eyes, waiting to see what I’d do next. I reached back into the crib and touched the black fuzz on his head, gently this time.

“It’s okay, baby,” I whispered.

I kept my hand on him until the long fringes of his eyelids drifted shut and he fell back to sleep.