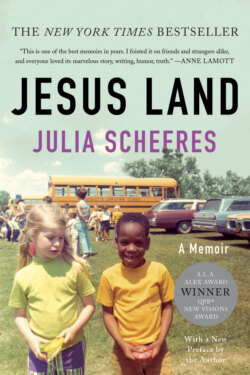

Читать книгу Jesus Land - Julia Scheeres - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

EDUCATION

I’m fully awake and staring into the moon face of the alarm clock when it starts to clatter at 5:30. Acid surges up my esophagus. This is It. The Day That Will Determine Everything. Whether we are Winners or Losers. Predators or Scavengers. Rejects or Normal. It’s the first day of school.

Through the bedroom window, dawn reddens the horizon. I jump up to turn on the ceiling light and sway momentarily in the blinding whiteness. In the dresser mirror, I examine my face—no new zits, Thank You, Jesus—before thrusting myself into a blue Kmart polo shirt that matches my eyes and a pair of baggy jeans. I tried baking them in the dryer for six hours while Mother was at work, but they refused to shrink.

In the bathroom, I lay out the tools of beauty—curling iron, ultra-hold Final Net, frosted pink lipstick—on the counter and tape a picture of Farrah Fawcett to the mirror. I ripped it out of a magazine at my dad’s office and have locked myself in the bathroom every night for the past week to practice her hair, her eyes, her smile.

After I finish painting my face and crimping my hair, I shellac my head with haispray and step back to survey the results. I look at Farrah, I look at me. I look nothing like Farrah. My eyes are too small, my mouth too large, my hair too limp. But we’re wearing the same shade of turquoise eye shadow, and I suppose that counts for something.

I’ve decided to make a party impression at Harrison. Party hardy. That shy girl who barely raised her head at Lafayette Christian is gone. The new Julia will throw back her head and laugh as if she didn’t have a care in the world. And this laughter and happiness will make her attractive to people and win her admiration and friends.

But first I must get into a party mood. I lock my bedroom door and pull a mayonnaise jar swirling with amber liquid from a box of sweaters in my closet. Southern Comfort. It helps my parents laugh when they stir it into their bedtime cocktails, so I figure it should help me too. I’ve been siphoning it from the bottle bit by bit whenever Mother forgets to lock the pantry.

I tilt the jar against my lips and the booze blazes down my throat like hot sauce. I’ve been practicing this as well, and now know the first swigs are always the hardest. I plug my nose and hop from foot to foot until the fire subsides, and after the fourth swallow my taste buds are numbed enough that I can dump it down like water.

When I bend to slip on my plastic Kmart shoes, I lose my balance and fall giggling against the closet door, my insides warm with the boozy embrace. The intercom crackles.

“The bus leaves in thirty minutes,” Mother says. “You miss it, you walk.”

“I’m getting ready already!” I yell at the speaker.

Good morning to you, too. I take another swig of Comfort. Not a care in the world.

At the breakfast table, David sits over a bowl of cereal as Rejoice Radio—the soundtrack of our family life—blares in the background. He’s also gone to special lengths for the Big Day. He’s hot-picked his Brillo pad hair into a soft halo. Wiped the smears from his glasses. And traded in his usual T-shirt and jeans for a short-sleeved white oxford and khaki slacks—an outfit demanding respect.

“I see you busted out the ‘No Mo’ Nappy’ this morning,” I say, sliding into the chair across from him. He gives me a grim look and goes back to staring into his cereal.

For some reason it’s okay for him and Jerome to tease each other about their hair ointments, but if I join in, they get huffy. I tried one of their products myself in seventh grade, lured by the label’s promise of “tresses that glow with the silky sheen of Africa.” Queen of Sheba Conditioner it was called, and I caked it on. It made me look like I’d dipped my head in bacon fat, and I was able to rid myself of it only after a week of scrubbing my hair with dish soap and baking soda. The boys called me grease ball for months afterward.

I fill my bowl with generic bran flakes. I can feel the alcohol spread through my body as I chew the cardboard flakes. A hymn I recognize comes over the intercom:

Asleep in Jesus! Blessed sleep,

From which none ever wakes to weep;

A calm and undisturbed repose,

Unbroken by the last of foes.

I wag my spoon over my bowl like a conductor’s baton and David raises his head.

“What’s your problem?” he says.

“Great tune.”

“It’s about death.”

“Yeah,” I shrug. “But it’s got rhythm.”

He cocks his head and stares at me.

“Somebody punch you in the face or something?”

“What?”

“Your eyes are all bruised.”

“It’s called eye shadow, goof ball.”

“Oh. Is it supposed to be attractive?” he asks, before cracking a smile. “Just kidding!”

“Ha ha,” I say, smiling back at him. At least he’s joking around; this means he’s not totally freaked. This is good.

“Meet you out back in ten,” he says, standing to gather up his breakfast things.

“Alrighty.”

After breakfast, I gulp down more Comfort, brush my teeth, and slide bubblegum lip gloss over my mouth. In the mirror, I am a collage of yellow, pink, blue. I practice my Farrah smile, head back, teeth bared. Not a care in the world.

Mist hovers over the back field, and we trudge in silence through the knee-high prairie grass, which brushes our pant legs with dew and tiny seeds; Dad hasn’t had time to mow it. The bus stop is at the end of the lane. My head is spacey and light, like when David and I were little and spent hours spinning in circles with outstretched arms for the simple rush of falling down in a dizzy, laughing heap. I wish we both had that feeling now, I think, looking at David as he worries his bottom lip.

On the gravel lane, a killdeer limps ahead of us, dragging a wing and crying pitifully, trying to distract us from the four speckled eggs lying camouflaged at the roadside. I glance at David—he’s scowling at his feet, ignoring the bird—then look away from him, not wanting his anxiety to contaminate my numbness. Not a care in the world. Think Farrah. Think laughing, happy, beautiful people. Think shampoo commercials.

The lane ends in an abrupt T at County Road 650, and I drop my backpack on the ground next to a bank of plastic mailboxes and lean against them. David busies himself plucking hitchhikers from his slacks.

A rooster crows in the distance and a breeze, perfumed with fresh-cut hay, flits over us. I turn my face into it, breathing deeply, and close my eyes.

Several minutes pass. There’s a faint clatter that grows louder and I open my eyes to see headlights tunneling toward us through the mist. David stiffens before recognizing the unmistakable rattle of a tractor, then goes back to pacing the road.

When the giant machine clanks into view, the farmer riding it lifts his arm at a right angle to his body as if he were swearing on the Good Book, and I wave back grandiosely, with both hands, as if I were the Queen of the Rose parade. Party Hardy.

After the farmer chugs by, David walks to the middle of the road, crosses his arms, and squints into the mist.

“You in a hurry to go somewheres?” I yell over the tractor’s wake. He doesn’t answer, and I laugh and it comes out as a belch, and I laugh again.

As I’m practicing a hip-thrusting dance move I saw watching American Bandstand while Mother was at work, the low roar of a diesel engine rises over the fields.

David backs up to the side of the road, and I pick up my backpack and stand beside him.

“Relax,” I tell him.

“Easy for you to say,” he says, giving me a knowing—and disapproving—look. So he knows I’ve been drinking. So what. He’s always been such a goody-two-shoes.

We both turn to watch the headlights grow brighter. It’s the school bus, No. 26, just like it said in the letter. The yellow tube shudders to a stop ten feet past us, and as we walk around it, I keep my eyes on the ground. We’re at the end of the route, and it’s full of kids by now, all staring down at us through the windows, sizing us up. Not a care in the world.

The door folds open with a bang.

“There’s s’posed to be three kids at this stop! Where’s the third one at?” shouts the driver, a fat woman in a purple pantsuit. The ceiling light above her seat makes her white bouffant glow like a sunlit cloud. She studies the clipboard in her hands as I climb the short stairway.

“Name, first and last.”

“Hello, my name is Julia,” I say brightly. “Julia Scheeres.”

She crosses my name off her list and looks up as I step aside for David. Her mouth drops open when she sees him, and she turns back to me.

“Who’s that?” she asks.

“I’m David Scheeres,” he answers quietly.

Her eyes dart between David and me.

“He’s my brother,” I say impatiently, aware of a murmuring behind us.

“Brother, huh?” she says flatly, as if I were lying.

“Brother, yes.” I bend to find his name on her list and tap on it. “Right there. David Scheeres.”

She crosses out his name, shaking her head. Why does this have to happen today, of all days? Can’t we please be normal just for once? My heart crimps despite my fuzzy-headedness.

“And where’s the third kid?” she asks, lifting her list to her face, frowning.

“That would be Jerome Scheeres. He won’t be joining us today.”

She arches her stenciled eyebrows.

“Jerome, huh?” She grunts and scribbles something next to his name before scooping a hand toward the innards of the bus. “Go find yerselves a seat.”

I swivel around; rows of white faces point in our direction. A pocket of space materializes at the back of the bus and I throw my head back, put on my Farrah smile, and I sashay down the narrow plank of the aisle, carefully avoiding protruding limbs. Not a care in the world.

Two rows before we reach the empty bench, a black boot slams down in front of me, heel first. My eyes sweep over it and up the jean-clad leg and the United Methodist T-shirt to the orange hair of the boy wearing it. It’s one of them. One of the graveyard boys. Beside him sits a smaller, orange-haired kid with the same pug nose; they must be kin. Brothers.

The graveyard boy glares up at me, his eyes sparking. A corner of his mouth jerks upward like a growling dog.

“Nigger lover,” he snarls. There’s spit tobacco stuck in his gums. I stare at his mouth.

My Farrah smile collapses and hatred wells up in me, too, matching his hatred ounce for ounce, but there’s also fear kicking at my ribcage. The bus lurches forward and I stumble over his leg and fall onto the empty bench. When I look up, David’s swaying in the middle of the aisle, gawking down at the boot.

I stand. “David!”

He gingerly lifts his foot over the boot and when he’s mid-stride, the boot rockets up and slams into his crotch. Laughter clatters around us, and the graveyard boy joins in as he retracts his leg. David twists his mouth into a sick smile and shakes his head, as if he were dealing with a mischievous child.

I grab his wrist to pull him to the bench, pushing him into the spot next to the window. For the duration of the ride to Harrison, as ripe cornfields whisk past the bus windows, David keeps his head bent and his eyes clamped shut. I try to pray, too, but my mind goes blank after the “Dear God.”

The bus rumbles up Harrison’s curved driveway and stops at the end of a long line of yellow buses. We wait until all the other kids drain out to join the throng of bodies moving up the sidewalk before standing. The driver watches us walk up the aisle in the rearview mirror, but turns her head when she sees me glaring at her. Witch.

At the school entrance, two middle-aged men in dark suits, Principal Day and Assistant Principal May—we were warned during orientation that yelling “May Day!” would get us an automatic detention—stand on opposite sides of the doorway, greeting students.

“Welcome back!” Principal Day says to me as we cross the threshold. Assistant Principal May looks blankly at David, who glances at him then looks away.

As we walk side by side over the foyer’s gold linoleum floor, I try to catch David’s eye, but he’s scanning the crush of white faces, searching—as I’ve been—for a sign. A nod. A smile. A kind look. A potential friend. Instead, there’s a lot of staring, a lot of whispering. A lot of eyes darting back and forth between us, and Dear God, I could use some Comfort now.

The foyer dead-ends in a cafeteria with a barnlike peaked ceiling. We wind through round blue tables in the center of the room to avoid a row of boys in baseball caps slumped against the wall.

“Woah, nice udders!” one of them shouts to a girl strolling by them. She presses her books to her chest and quickens her pace; they laugh at her.

Before we turn down separate hallways to our lockers, I grab David’s arm. He turns to me with wide eyes.

“Remember Florida,” I say. Remember there’s a better place than this.

He nods solemnly. I step away from him, and a moment later he’s engulfed by a wave of white bodies.

I locate my locker along the long gray wall of lockers and consult the palm of my hand, where I wrote the combination in permanent ink last night. After two tries, the door wobbles open and I dump the textbooks for my afternoon classes in the bottom of the narrow cavity. The first hour warning buzzer sounds over the hallway speakers, and the dim corridor reverberates with the sound of hundreds of lockers slamming shut. First hour starts in two minutes; get caught in the hallways after it starts, automatic detention.

I follow the stampede up a trash-strewn stairway to the second floor. As luck would have it, my first period is Algebra. Math, my worst subject. Most of the seats are already taken when I walk through the classroom door. The Preppies, all pink and green Izods and Sperry topsiders, have claimed the back rows, setting their backpacks on the chairs in front of them to wall themselves off from everyone else. Next to the window are the Hoods, in their black jeans and hooded sweatshirts. In the front rows are kids with pencils and calculators aligned on their desktops: the Nerds. The middle of the room is sprinkled with kids who don’t appear to fit into any of these cliques, the Unclassifiable Outsiders. This is where I sit.

The second warning buzzer sounds. It’s eight A.M. and there’s no teacher. I look out the corner of my eye at the girl sitting next to me. Her kinky red hair cascades down her back in a giant ponytail and she’s wearing hot pink leg warmers under a ruffled gray miniskirt. I’ve seen such getups on the pages of Glamour magazine, but never on the streets of Lafayette. She must be new, from some place big, a city. She’s bending over her notebook in absolute concentration, sketching. As I lean forward to get a closer look—tiger, a very good one—a man in a white shirt and blue tie strides to the front of the room and bangs his fist on the metal desk. The preppies stop chattering and everyone looks up, except the girl beside me.

“I’m Mr. An-der-son, and this is Al-ge-bra 1,” he says slowly, enunciating every syllable. He glances at the clock at the back of the room. “The time is 8:03. If you did-n’t sign up for Al-ge-bra 1, leave now. If you did sign up for Al-ge-bra 1, take out your text-book, face the front of the room, and shut up. Let’s make this as pain-less as pos-si-ble for ev-er-y-bo-dy.”

He speaks so slowly that I wonder whether we’re the idiots or he is. I dig Algebra for Life out of my backpack and set it on my desk along with a notebook and two sharpened pencils.

Mr. Anderson leans his broad shoulders against the blackboard and crosses his arms over his chest, surveying the room. He must have been a hunk, I think, before he developed man breasts and a gut.

“Hey you,” he calls to the girl sitting beside me. She continues doodling.

“Yoo-hoo!” he yells in a high voice. There’s laughter, and the girl looks up, startled, and slides an arm over her notebook. Her eyes are ringed in thick black liner. Mr. Anderson waves both hands at her.

“Who are you?” he asks.

“Elaine Goldstein,” the girl says, pronouncing it as Goldstine.

Mr. Anderson rubs his chin.

“Jew name, isn’t it?”

Elaine looks at him without responding as snickers spill from the back of the room.

“How do you spell that word, Goldstein?” Mr. Anderson asks. He pronounces it as if it ended in “stain.” Gold-stain.

“G-O-L-D-S-T-E-I-N,” Elaine spells, as Mr. Anderson writes it on the blackboard in capital letters.

“Miss Goldstain, kindly pay attention in my class.” He erases her name with a broad swipe of the eraser, then starts tapping out an equation.

“O-kay, peop-le, o-pen your text-books to Chap-ter One.”

Elaine’s arm drifts back to her notebook, where she draws two long fangs in the tiger’s mouth. A sabertooth. I drum my fingertips on the side of my desk nearest her, and she scowls over at me, her cheeks scorched with humiliation. I turn my head to stick my tongue out at Mr. Anderson—who’s still writing out the equation—then look back at her.

She smiles.

I look for David in the frantic crush between classes, but don’t see him.

I walk into each new classroom with a pounding heart, looking for a girl who’s sitting alone and glancing about as uncomfortably as I am, someone who’s also new to this circus. But by the time I locate each new room in the dark rambling hallways and rush inside with my Farrah smile, the desks are packed and I have to make do with a seat in or behind the nerd section.

By lunchtime, I still haven’t spoken to a single person. Mademoiselle Smith is standing in front of French class grunting “répétez: é È, eu, eau” in a constipated voice when the noon buzzer rings and kids launch themselves from the room without waiting for her to finish her sentence.

I ignore the mass exodus and slowly copy the homework assignment into my notebook, putting off for as long as possible the moment I’ve been dreading all day. When I finish, I zip up my backpack and stand, the last student in the room.

“Bon appétit,” Mademoiselle Smith calls to me as I walk out the door.

I find a bathroom and check myself in the mirror. My Farrah curls have unraveled and my Farrah eye shadow lies in turquoise pools under my bottom lashes. I squirt liquid soap onto a paper towel and scrub it off over the sink.

In the hallway, lunchtime noise rises from the first floor like the drone of a hornet’s nest. I walk past a drinking fountain clogged with spit tobacco to the stairwell, walk down it, and observe the cafeteria through the small window in the metal door. On the far side of the room, there’s a job fair. Tables have been pushed together and a banner is taped to the wall: “EXCITING career OPPORTUNITIES with Lafayette’s LEADING employers: Caterpillar, Taco Bell, Alcoa. Get a Head Start on Life!”

Most of the round blue tables are filled, and a food line winds along one wall. I open the door, my stomach sour with nerves and whiskey, and stride purposefully toward it, as if someone were waiting for me, holding a space.

At the round blue tables I again recognize a seating arrangement: The center of the room belongs to the Jocks and the Preppies—the popular kids—and surrounding them are the lower orders—the Nerds, the Hoods, the Farmers, the Unclassifiable Outsiders.

As an unsmiling row of ladies in hairnets and aprons take turns spooning food into the compartments of my lunch tray—creamed spinach, tuna casserole, butterscotch pudding—I scan the room for David. He’s nowhere in sight. Neither are Elaine or Mary.

I hand the cashier the $2 Mother gave me and face the room.

A girl with a side ponytail and stirrup pants stands a few feet away from me, also holding a tray and looking around. Maybe she’s new, too. Maybe I should talk to her. But what would I say? Hi, are you new, too? That sounds so dorky! As I ponder this, a girl at a center table jumps up and yells “Christie!” and she rushes away.

The aroma of warm mayonnaise and dill pickles from the steaming casserole is making my mouth water. Where should I sit? What group should I join? Where do I belong? There doesn’t appear to be a table for Unclassifiable Outsiders. I search the room for someone, anyone, sitting alone, and my eyes drag across the orange-haired boy. He’s sitting with a bunch of farmers along the back wall, facing my direction. He hasn’t noticed me yet. I watch him fork spinach into his hateful mouth, then I walk to a conveyor belt jerking dirty trays behind a wall and set my lunch on it.

There’s a vending machine in the basement, next to the gymnasium. I buy a pack of Boppers and a Tab. I try the locker room door, but it’s locked. So is the gym. Through the glass doors, the wood floor gleams in the pale light cast by the high windows, and the empty bleachers await the next event. A large clock on the far wall says 12:50. Fourth hour starts in ten minutes.

I find a girls’ bathroom down the hallway and try the door. This one’s open. I walk into a stall, slide the metal latch closed, and sit down to eat.

I’m the first to board bus No. 26 after school. The driver motions to the seat behind her when I climb in.

“Y’all sit here for the meanwhiles,” she says, studying her three-inch-long nails, which are painted the same shade of purple as her pantsuit. I slide onto the bench and pretend to read my French book as kids erupt from the school building, yelling and laughing and chasing each other down the sidewalk. As the bus fills, I worry that the driver will leave without David. I stick my French book into my backpack, preparing to get off when she starts the engine if he isn’t here. I’ll find him and we’ll walk home together.

As the driver fiddles the radio to some whiny country music station, I see David rushing down the sidewalk, head down, hands clasping the shoulder straps of his backpack.

“There’s that nigger,” I hear a male voice say behind me.

David stomps up the stairs with a tense face, and presses his lips together as the driver loudly informs him about our reserved seat.

“Scaredy-cat!” a boy calls as David sits down next to me. “Wuss!” David doesn’t look at me.

On County Road 50, the bus gets stuck behind a combine that crawls down the road like a giant metal stink bug. I stare out the windshield, willing it to pull over and let us by. When the driver jerks to a stop beside the bank of mailboxes at the end of our lane, we’re already standing, trying to get out.

I turn to David when we’re halfway across the back field. The Indian summer air is thick with dirt and pollen, the afternoon still but for the lone grackle cawing atop the clothesline.

“What’d you do for lunch?” I ask him. He shrugs and looks at the ground.

“You?”

“I ate some candy.”

He nods, and we walk the rest of the way to the back door in silence, because there’s nothing more we want to say.

After a few days, things settle into a routine. I chug Comfort each morning, not to conjure a party attitude, but to numb myself to the snickering that breaks out when David and I slide into our reserved bus seat.

After hearing “nigger lover” and “there goes nigger and his sister” hurled at our backs too many times, I stop walking into school with him.

Seems we can never just be brother and sister like in other families. Our whole lives, people have felt an urge to make up special names for what we are. At Lafayette Christian, we were the “Oreo twins” or “Kimberly and Arnold” after the characters on Diff’rent Strokes. And while those nicknames bugged us, they were certainly preferable to what they call us at Harrison.

“See ya later!” I tell David when the bus door flaps open in front of Harrison. As I rush down the sidewalk ahead of him, I feel a pinch of guilt, but a greater relief as I melt into the sea of white bodies. Alone, I am part of the crowd. Together, we invite notice and ridicule. Why do I always have to be the “black boy’s sister” anyway? Why can’t I be my own person? It’s not fair. This is a new school, and I want a fresh start.

Besides, people will think David’s a sissy if he’s always hanging around me. It’s best for him, too. We’re sixteen, and it’s time we struck out on our own.

Sometimes I run into him between classes, always alone, always rushing and looking straight ahead, his face a blank mask. He’s easy enough to spot because he’s the only black kid at Harrison. A couple of times, he’s rushed right by me without seeing me—I must have been just another white face to him, blurring by. Once I almost reached out a hand to touch him and say his name, but then thought better of it. It’s better for both of us like this.

During Algebra, I’m tipsy enough to start making small talk with Elaine. One day I compliment her white hoop earrings. The next, I ask to borrow her eraser. Then I run into her while I’m buying lunch from the basement vending machine.

She’s crouched outside the glass door leading to the parking lot, her body hidden but her unmistakable red hair blowing sideways across the glass. I buy an extra can of Tab.

She jumps up when she hears the door open and chucks something into the grass before whipping around to face me.

“Jesus Christ, don’t sneak up on people like that!”

I wince at this blasphemy as she bends to search for whatever it is she threw into the grass. Today she’s wearing a pink-and-black striped top that slumps off one shoulder, a jean miniskirt, and ankle boots that have these lacey white baby socks frothing out of them. She looks like that whorish new singer, Madonna. I’ve heard preppy girls poke fun at her behind her back and call her a slut, but Elaine doesn’t seem to care whether she fits in at Harrison or not. I admire her for it.

She straightens, a lit cigarette in her hand. “Sorry, I’m a little on edge,” she says. “How’d you find me?”

“It’s alright,” I say. “I was just buying some food and saw your hair in the window.”

She gathers it to the side of her neck with her free hand and laughs. “Oh damn. Didn’t think of that.”

I stand awkwardly holding the two cans and a Snickers bar as she sucks at her cigarette and squints at a pile of dark clouds on the horizon. I’ve never met a Jew before. Didn’t know there were any in Lafayette, or Indiana for that matter. Jesus-killers, we called them at Lafayette Christian. But Elaine doesn’t seem like a bad person. A gust of wind tugs at our hair.

“Want some pop?” I finally ask her, holding out a can.

“Sure,” she says, taking it from me. “Thanks.”

Maybe I could invite her to church one Sunday. I could convert her, introduce her to Jesus. Maybe she secretly hankers for Him like those Third World heathens.

A cow moos loudly across the road, and we turn to watch it plod into the mouth of the graffiti barn, which was raided last weekend by Westsiders. “Harrison Hicks Suck Dick” it says in big red letters.

“Where you from?” I ask her.

She takes a sip before answering.

“Chicago,” she says, looking at me. “Ever been?”

She is from a big city; I knew it!

“Yeah, in seventh grade,” I say nonchalantly. “We went on this field trip to the Museum of Science and Industry.”

I don’t tell her that our bus driver got lost in the ghetto and a policeman took pity on us and escorted us to the museum.

“My dad was hired as a chemist at Eli Lilly, so that’s why we had to move here,” Elaine says.

The wind shifts, blowing the stench of fresh cow manure over us, and she wrinkles her nose and tells me how sorely she misses “civilization.”

“Did you know that the very word Hoosier means country bumpkin?” she fumes, stubbing out her cigarette on the heel of her ankle boot. “Don’t believe me? Go look it up in the dictionary. Hoosier, it says. Synonymous for hick, hillbilly, back-ass-ward.”

I feel insulted, but bite my tongue. I’m in no position to be choosy about friends. We drink our pops and watch cows lug themselves into the dark barn one by one. The buzzer rings inside the building, signaling the end of lunch, the beginning of rejection, again.

“Will you be here tomorrow?” I ask Elaine, trying to control the desperation in my voice.

“Maybe,” she says, shrugging. “You?”

“Probably.”

“See you then,” she says.

As I turn to walk through the glass door, happiness bubbles through me. I’ve got someone to eat lunch with; I’m not a complete reject after all.

We meet at the cafeteria snack bar, loading up on Tab and Baffy Taffy and Funyuns before going outside.

Elaine prefers to talk, and I prefer to listen, so we get along great. As we eat our junk food picnic on the sidewalk outside the gym, she tells me about Chicago—the Water Tower mall, the Cubs baseball games, the Lincoln Park Zoo—and explains why everything is bigger and better there than in Lafayette.

One day we’re walking toward the stairwell with our food when a figure emerges from the boys’ bathroom ahead of us. It’s David. He ambles up the hallway, head down, kicking at a piece of balled-up trash.

I fight an urge to call out to him and ask him where he’s going and why he isn’t eating. I can’t be my brother’s keeper forever.

“See that black boy?” Elaine whispers, slowing down. “He’d be better off in Chicago.”

I nod and watch David disappear around a corner, then hold out my bag of Funyuns to her.

“Tell me about that shopping mall again,” I ask her as she dips her fingers into the yellow foil. “The one with the seven floors.”

Mary joins us. I spot her one day while we’re standing in line at the snack bar. There’s a commotion in the middle of the cafeteria, and we turn to see a pair of jocks in muscle shirts wrestling across the floor. They bump up against the cheerleaders’ table, and the cheerleaders shriek with delight; this is a show put on for their benefit. When the lunchroom monitor—a grumpy, man-like woman who sometimes works the snack bar—blows her whistle, the boys tumble apart and the cheerleaders stand in unison, clapping their hands in rhythm and chanting.

“Those are some fucked-up mating rituals,” Elaine sneers.

As I nod my agreement, I glimpse a lone figure in a yellow shirt at the far end of the cafeteria. David? He was wearing yellow today. I squint. No, it’s Mary.

“I’ll be right back,” I tell Elaine.

She’s sitting alone hiding behind her long bangs, but she smiles as I walk toward her.

“Where you been at?” I ask her.

“I had strep throat,” Mary says, “but I’m not infectious now.”

I point toward the snack bar. “Me and this other girl are gonna eat outside, wanna come?”

She wraps her cheeseburger in a napkin and follows me across the cafeteria. As we wind through the blue tables, I spot David sitting in a corner with Kenny Mudd, a nerd from my Algebra class. Everyone calls him Casper because he’s albino; his skin is translucent, and his buzzed hair and eyebrows platinum blond. He wears bottle-thick glasses that make his red eyes bug out, and he’s brilliant. Sitting across from each other, David and Kenny look like each other’s photographic negative.

I watch David pick up a French fry and cock his head to one side as he listens to Kenny talk. He’s not looking in my direction, but I grin at him anyway. He’s eating proper and he’s found a friend, even if that friend is Kenny Mudd. The lunch monitor frowns at me as we walk by her, and I smile at her, too, happy that this big grumpy woman is watching over my brother.

We’re okay, we both are.

We organized a “welcome home” party in the basement. Debra put David on the couch and Herb Alpert on the turntable, and while the rest of us boogied across the carpet, David screeched and bounced on the cushions.

Mother raced downstairs and turned off the music.

“No dancing for David,” she scolded. “It’s too much for him.”

He was almost three years old, but he couldn’t walk, and he couldn’t talk. He scooted around on his hands and knees. Such was the legacy of his foster-care “families.” When he wanted something, he’d point at it and scream. If we didn’t understand him, he’d hurl himself to the floor in shrieking frustration, and he’d do the same if he didn’t get what he wanted.

He had other residue from his family services days. He’d bang his head against his crib board and fall asleep in his high chair, face-planting in his oatmeal.

I appointed myself his warden and his keeper. I pulled him around by his arms until he took his first teetering steps alone, and clapped my hand over his mouth until he learned to pronounce the names of the objects he wanted.

My name was too difficult for him. He followed me around chanting “Ju-la-la,” and I called him “Baby Boo-Boo” because he was constantly tripping and falling and scraping his skin. I’d kiss away his pain and hush his cries.

He was my baby.