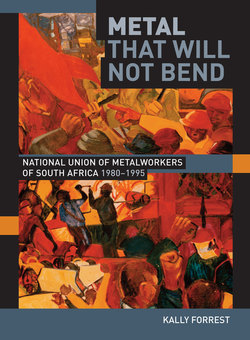

Читать книгу Metal that Will not Bend - Kally Forrest - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

National auto union

ОглавлениеThe launch of Fosatu in 1979 strengthened organised workers and helped to draw the unorganised into its industrial affiliates. Also, the federation was better placed to take up non-factory issues at local and national levels. As a ‘tight’ federation, it provided common resources to affiliates and helped them build membership. Regional councils were set up to ensure cooperation; they and unions were frequently based in the same buildings. According to Fanaroff, ‘We used to share organisers. The Fosatu secretary in each region was the organiser of last resort. It was share and share alike, we shared photocopiers, benches, desks, cars, organising, strikes.’2 Fosatu gave workers a concrete vision of unity in action, and was a model for future unity moves.

National Union of Automobile Workers Union (Naawu), United Automobile Workers (UAW) and Western Province Motor Assembly Workers’ Union (WPMawu) at a joint motor conference. L-R Alec Erwin (Fosatu); Johnnie Mke (UAW); Joe Foster, James Campbell (shop steward) and Natie Gantana all of WPMawu; and Brian Fredricks of the International Metalworkers Federation (IMF) (Wits archives)

Numarwosa, which had first mooted the formation of Fosatu, was the first union to embark on industrial union unity. When Numarwosa set up its parallel union, UAW, its aim was to organise Africans until the new union was strong enough to merge with them. Later, Numarwosa and UAW were thrown together with WPMawu in talks leading to Fosatu’s formation. The participation of these three unions on the South African Council of the IMF had brought the Eastern Cape auto unions Numarwosa/UAW closer to WPMawu, the Western Cape auto union, especially as they all opposed the racist Confederation of Metal and Building Unions (CMBU) which was also represented on the council.

When the SA-IMF was formed in 1974, the CMBU unions were in command. They had official bargaining rights and links with IMF leaders abroad who supported racially-separated unions. In 1980, the Fosatu metal unions walked out of the council, accusing it of racism. The IMF Council was relaunched after Fosatu drew up conditions for membership, including ‘genuine shop floor cooperation’3 and non-racialism, and forced the council to expel two segregated craft unions. The new IMF Council consisted of nine metal and motor unions which variously belonged to Cusa (Council of Unions of South Africa), Fosatu and Tucsa and represented 200 000 metal workers. The unions immediately took a resolution condemning poverty wages, influx control and apartheid.4

Naawu National Executive Committee (NEC) in March 1986. Note Daniel Dube front row second from right (Wits archives)

Cemented by this struggle, Numarwosa, UAW and WPMawu merged in October 1981 to form the National Automobile and Allied Workers Union (Naawu), with 17 000 members in Cape Town, Durban, Pretoria, East London and Port Elizabeth. Naawu immediately registered with the Department of Labour, bringing the African UAW, with 5 000 members, officially on board. Because of its roots in Tucsa, Naawu was unlike Mawu in important ways. Taffy Adler explained:

Naawu was more organised bureaucratically than Mawu partly because of the Tucsa tradition. At one point the union had uniforms for women who worked in the offices in PE. There was a level of organisational capacity which was admirable; there was a management committee at the provincial and national level where issues were discussed; there were definite lines of authority and responsibility – national exec, national office-bearers’ committee, reports that went out, financial reports, records of decisions taken. You knew there was someone in control who recognised and exerted that authority, and that was based in PE at the time.5

Gavin Hartford, a Naawu and later Numsa organiser, recalls the personal service Naawu gave members, in the Tucsa tradition of administering benefits:

We were going once in the car with Les [Kettledas] to the airport in between two strikes and he popped out of the car and went to the deeds office to process a deceased member’s estate. That was the kind of service they provided. They saw the worker through from the cradle to the grave … when the member died the family would come and say, ‘Uncle Les has detailed knowledge, he’ll know what do we do now.’

Naawu Transvaal AGM in May 1983 (Paul Weinberg)

They knew the Basic Conditions of Employment Act backwards. They knew the estate law, the LRA, the constitution of the Industrial Council, they knew the minutes of every meeting, they knew the agreement backwards. This was the Tucsa tradition … You were a bureaucrat, you knew your documents … you always had the government gazette and you always read it. You worked very closely with the Department of Labour. Never mind the registration debate at the time, the Department was your ally and you knew the Department officials.6

In the early days, the 1970s and early 1980s, the union collected members’ dues in the same tedious way as Mawu did – the only difference was that it had administrators. Once Naawu had negotiated company-level recognition, stop orders followed and it became better-resourced than Mawu. Every Naawu official had a car, for example, whereas in 1984 23 Mawu officials shared four vehicles. The auto union, also unlike Mawu, only relied on outside funding for special projects such as the organisation of factories in the Transvaal. Registration encouraged it to maintain tight financial and administrative procedures, as Kettledas explained:

We had to keep proper records in terms of the [Industrial Conciliation] Act. We had to have our books audited and submit our audited statement to the Department of Labour. We were also running benefit schemes, and it was important we have accurate records … there had to be income and expenditure statements for both the unions and the funds on a monthly basis, presented to the branch executive committee. And we had very strict treasurers, treasurer at branch level, treasurer at regional level, treasurer at national level and a finance committee which had to meet regularly. We had branch quarterly general meetings and the membership were quite vigilant … you could get very detailed questions, from the floor, on your financial statements. I can remember that people were very nervous when it comes to branch general meetings … we just kept our head above water … I can recall that for four years all staff of the union never received a salary increase … and we accepted that. I started with R250 a month in 1974, and by 1980 I was earning about R750.7

Trade union unity summit in Athlone, Cape Town in 1983 (CDC)