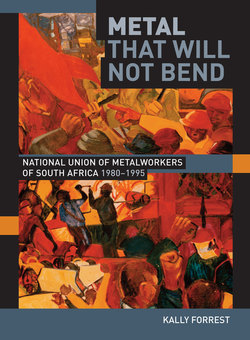

Читать книгу Metal that Will not Bend - Kally Forrest - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The 1970s: new light

ОглавлениеBy 1973, the economy was slowing, and by 1978 it was in deep recession. For metal workers on the East Rand, these were ‘lean years’.9 Forced removals placed intolerable pressures on the overcrowded reserves, and huge numbers of desperate people flooded into the cities in search of work.

In this context, two ruptures changed the course of South African history. In 1973, a wave of spontaneous strikes erupted in the Durban industrial centre of Pinetown; an estimated 70 000 workers in different industries downed tools and demonstrated that beneath the quiescence of the 1960s rankled resentment at low wages and stressful working conditions in the face of flourishing industries and employer prosperity. (In the early 1970s, inflation eroded wages as labour confronted price rises of up to 40 per cent on basic goods;10 in 1973, the average African pay was R13 a week, well below the R18 stipulated by the Poverty Datum Line.) The strikes brought to the fore the inadequacies of South Africa’s dual labour relations system and signalled a reawakening of working class militancy – new trade unions were formed, including Mawu, which aimed to organise African workers. The strikes also shocked employers into realising that new systems of control were necessary and as a result the Bantu Labour Relations Act was passed, which introduced non-union management/worker structures known as liaison committees. It soon became apparent however that they were no substitute for union organisation, as strikes continued to erupt. Between 1973 and 1976, the number of African workers involved in industrial action each year never fell below 30 000.11

The next rupture in the fabric of the apartheid state occurred in 1976. In the economic boom of the early 1970s, industry experienced a shortage of skilled manpower, which pressured the state to provide better education for black people. An increase in the number of black high schools and of places at universities for black students led to a substantial increase in the number of black intellectuals, many of whom embraced the Black Consciousness ideology which was partly responsible for the student uprising, starting on 16 June 1976, to protest the Bantu education system and, in particular, Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. The uprising marked the reappearance of the ANC on the South African political horizon, as thousands of youngsters fled to neighbouring countries and were recruited into its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe.12 The children of the Soweto riots were also the workers of tomorrow and from the late 1970s onwards a wave of politically conscious students entered the labour force. They were to be highly responsive to union organising drives.

Durban strikers in 1973 (unknown)

In response to the growth in union organisation and the mobilisation of black youth, a generation of reformers, guided by new prime minister, PW Botha, emerged in the Nationalist government. In Botha’s government the South African Defence Force (SADF) played a significant policy making role; on its instigation Botha pursued a ‘total strategy’ and reform programme in response to an ostensible ‘total onslaught’. The strategy aimed to reduce foreign pressure on apartheid, remove the Marxist ANC from South Africa’s borders, and promote a black middle class to counter radical township activity. On the labour front, the Riekert and Wiehahn Commissions were appointed to investigate the pass laws and labour legislation respectively. The 1979 Riekert Report recommended that the African population be divided into urban ‘insiders’ with residence rights and homeland ‘outsiders’. Simultaneously, the Wiehahn Commission recommended that Africans be brought into the statutory industrial relations system and that job reservation be scrapped. In 1979, the minister of labour abolished job reservation – except in mining – and metal employers and the white unions agreed to end closed shop agreements barring Africans from certain grades of work.13 These commissions would critically alter the apartheid landscape of the 1980s.

Against this upheaval and change, Numsa’s predecessors, each with its own history and traditions, began organising coloured, Indian and African workers. For those organising Africans, the obstacles were the greatest but for those organising coloured and Indian workers the challenge was to forge non-racial solidarity with Africans.