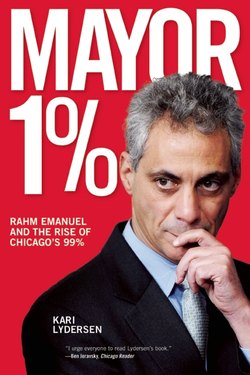

Читать книгу Mayor 1% - Kari Lydersen - Страница 15

Оглавление4

Rahm Goes to Congress

Emanuel’s brief career in investment banking was clearly a great success. But he studiously avoided talking about his foray into the private sector when he made his next career move: running for Congress in Illinois’s Fifth District.

The district represents more than half a million people, and stretches from lakefront high-rises on the east to unassuming blocks of typical Chicago bungalows further west, including several suburbs. It includes neighborhoods full of nightlife, such as the Boystown gay district; Wrigleyville, home to the Cubs’ ball field; as well as quiet upscale residential enclaves like Emanuel’s Ravenswood neighborhood. The median household income in 2000 was about $50,000.1 The district was about three-quarters white and about a quarter Latino, with small African American and Asian populations.2 The population logged as white by the Census was actually a prime example of ethnic Chicago, including a large number of Polish immigrants and Polish Americans, German Americans, numerous Bosnians and Russians, and a significant Jewish community.3

Emanuel reportedly decided to run for Congress almost on a whim after a certain Illinois politician jogged by while Emanuel was in the yard playing with his kids. Rod Blagojevich, who was then serving as congressman of the Fifth District, stopped his workout long enough to tell Emanuel he was thinking of running for governor.4

Two significant Democratic candidates had thrown their hats in the ring for Blagojevich’s seat before Emanuel entered the race. They were Bernie Hansen, an alderman who’d been in City Council since 1983 and was a longstanding member of the famous Chicago Democratic “Machine”; and Nancy Kaszak, a state representative and lawyer of Polish descent.

Hansen dropped out of the race abruptly after Emanuel declared his candidacy; insiders speculated that Mayor Daley had pushed him to quit.5 Such machinations are common in politics, but in Chicago they happen in the special context of the Machine. By the turn of the twenty-first century, many experts considered the Machine defunct, yet its legacy and dynamics certainly played a role in Emanuel’s political career—including in his congressional bid.

“The Machine” refers to the powerful Democratic Party organization that has controlled many of Chicago’s political posts and other power structures since it was launched in the 1930s by Bohemian immigrant mayor Anton Cermak, who accumulated and maintained power in part by doling out thousands of patronage jobs with city agencies and appointments to political posts, demanding loyalty and legwork in return. Deciding which candidates will get party backing or even run at all was a hallowed Machine function. Machine support was long considered key to winning Chicago elections, because the Machine turned out patronage workers to campaign for and donate to chosen candidates while undermining opponents.

The Machine’s grip on Chicago has loosened and tightened at various points over the years, with a defining figure being legendary Mayor Richard J. Daley, “the Boss,” who served from 1955 to 1976. The 1983 election of African American mayor Harold Washington broke the Machine’s traditional hold and launched the “Council Wars,” with City Council split between aldermen loyal to Washington and powerful ethnic white South Side alderman Ed Vrdolyak. One of Vrdolyak’s top lieutenants in the anti-Washington bloc was Irish American Alderman Ed Burke, who was still on the City Council when Emanuel took over.

Washington died in office after being reelected in 1987, and Daley’s son Richard M. Daley was elected mayor in 1989. Although the Machine changed in structure and diminished in power from the days of the Boss, some saw its traces in the multiracial, multiethnic yet top-down coalitions that the younger Daley assembled. Rather than outright racial conflict, as had been seen during past decades, Daley’s Machine formed mutually beneficial alliances with powerful African American and Latino leaders and groups including the Hispanic Democratic Organization. Patronage jobs were reduced by economic factors and a federal consent decree, but a modern if less omnipotent version of the Machine continued to deal in political clout, including in the awarding of city contracts to private businesses. So while many considered the Machine dead by the time Emanuel took office, others saw it in an altered state—still a formidable foe, and now with Emanuel very much a part of it.

A Chicago Girl

Nancy Kaszak was a well-known and well-liked figure in the community, a populist and liberal who had grown up in the blue-collar south suburbs. Her father worked two jobs, at an oil refinery in northwest Indiana by day and at Sears by night. Kaszak was the first in her family to graduate from college, with a business degree from Northern Illinois University.6

She had worked as a consultant, fundraiser, and official for universities and nonprofit organizations, including chief attorney for the Chicago Park District during Harold Washington’s term as mayor.7 She had a history of running as an independent against Machine candidates, including an unsuccessful bid for alderman in 1987, and the 1992 race where she unseated the Machine-linked incumbent to become a state representative.8 In that campaign her co-chair was Abner Mikva—the congressman and future federal judge for whom both she and Emanuel had campaigned in the past.9 In 1996 Kaszak ran against Blagojevich—also a state representative at the time—in the Democratic primary for the congressional seat then held by a Republican. Kaszak lost in a close race, with Blagojevich receiving an endorsement from Mayor Daley and help from his father-in-law, Richard Mell, a powerful alderman.10 Blagojevich went on to beat incumbent Michael Flanagan with two-thirds of the vote in the general election.11

As a state representative, Kaszak gained attention for her campaigns against night baseball games at Wrigley Field, in which she argued that they were a disruption and a hassle for nearby residents. She generally compiled a liberal voting record, earning high marks from unions, women’s groups, and community advocates.12

Kaszak was the granddaughter of Polish immigrants, and she worked her Polish roots. The Polish-language media and community leaders embraced her during her campaigns. She announced her Fifth District candidacy at the Copernicus Center, “surrounded by portraits of Polish kings,” as reporter Chris Hayes noted in a profile.13

A Machine Guy

Emanuel announced his candidacy in November 2001. In a rare move, Mayor Daley—who usually didn’t intervene in congressional races—gave his endorsement. He also helped Emanuel secure the backing of the all-important “ward bosses,” who are key in Chicago elections because they use their clout and influence to turn out scores of volunteers and voters for Machine candidates. Former mayor Jane Byrne, a native of the area, supported Kaszak, saying, “I think it would be wonderful for the Fifth District and for the city of Chicago if Nancy beat the political machine. It would also be a breath of fresh air for the Democratic Party.”14

So the Fifth District congressional Democratic primary matchup between Emanuel and Kaszak was a classic Chicago race pitting a Machine candidate against an independent with grassroots bona fides.

Kaszak was a local and a “regular Chicagoan” in a way Emanuel was not—given his Wilmette upbringing, East Coast liberal arts education, time in Washington, and millions of banking dollars. One of Kaszak’s ads showed her driving her own Dodge Intrepid through a modest neighborhood, juxtaposed with Emanuel sitting in the back of a limo talking on a cellphone.15 Early polls showed Kaszak ahead, with double-digit leads over Emanuel among women, independents, and blue-collar workers.16

Emanuel’s campaign focused on rebranding him as a Chicago guy, kind of like the Daleys—who, for all their wealth and power, still oozed the South Side, rough-spoken Bridgeport neighborhood from which they hailed. The campaign played up the ties Emanuel did have to working-class Chicago: His life until fourth grade in an apartment in the Uptown neighborhood. Sunday evenings at his grandparents’ Chicago home, in an unspecified location near a big park. His maternal grandfather, Herman Smulevitz, who came to Chicago as a child fleeing religious persecution. His Uncle Les, a twenty-three-year veteran of the Chicago Police Department. The Chicago Reader noted that a slick, lengthy campaign mailer mentioned Emanuel’s investment banking not at all but devoted a full page to Uncle Les.17

Even a decade before “Wall Street versus Main Street” and “the 99 percent” became popular memes, Emanuel knew that voters might be turned off by the knowledge of his quick millions. So in November 2001, his staff conducted a focus group of male voters, paying them $75 each to describe how they felt upon hearing that Emanuel had become rich by “setting up deals.”

Emanuel’s wealth dwarfed that of Kaszak, who released tax returns showing she had earned $203,000 in the previous two years and had assets between $64,000 and $260,000.18 Emanuel ultimately spent $450,000 of his own money on the campaign, along with generous contributions from his corporate and political backers. Kaszak got substantial support from the organization EMILY’s List, which backs prochoice women candidates.19 But she was still outspent by Emanuel: he would raise almost $2 million during the primary campaign, compared to Kaszak’s $888,000.20 The funding gap was especially damaging when it came to expensive television ads: Emanuel started airing them in mid-February, but Kaszak couldn’t afford air time until the final week before the March 19 primary.21

As if his money and Machine backing weren’t formidable enough, Emanuel also turned out to be a surprisingly effective campaigner in his first run for elected office. He had long been known as obnoxious, abrasive, and impatient—hardly qualities that lend themselves to kissing babies and empathizing with senior citizens. But reporters and pundits remarked upon his friendly, charming demeanor and his ability to connect with voters as he put in long hours at L train stations, senior centers, grocery stores, and other public places.22 Perhaps Emanuel had picked up some tips from his former boss Bill Clinton, famed for the ease and enjoyment with which he moved among regular people.

Emanuel secured the endorsement of the Chicago Teachers Union, which would become his nemesis a decade later. The Illinois AFL-CIO also endorsed him after some nail-biting among Emanuel’s people over whom the labor federation would choose. Emanuel found out he’d secured the AFL-CIO endorsement during a breakfast interview with Reader reporter Ben Joravsky, and the newly warm-and-fuzzy candidate was so happy he jumped up, hugged, and gave a noogie to “my new best friend,” as Joravsky told it.23

Kaszak had a 94 percent approval rating from the AFL-CIO, but apparently Emanuel’s clout and Washington connections trumped her more grassroots and state-level credentials. The Nation quoted Illinois AFL-CIO political director Bill Looby saying, “She had the good labor record, but he had the record of knowing his way around Washington. The feeling was, he could be more effective in Washington.”24

Emanuel’s role in NAFTA apparently didn’t sway the AFL-CIO to support Kaszak. But EMILY’s List spent $400,000 on Kaszak’s behalf, funding ads that hammered Emanuel’s central role in NAFTA and noted that the trade agreement had cost Illinois eleven thousand jobs.25 (Emanuel media adviser David Axelrod, who would later serve as a top campaign adviser and then senior adviser to President Barack Obama, decried the ads as unfair attacks.)26 Kaszak’s campaign also spotlighted Emanuel’s involvement with welfare reform and the controversial merger that created the energy company Exelon.27

Meanwhile, Emanuel lambasted Kaszak for being soft on crime, invoking several state legislative votes wherein she appeared to oppose stiffer sentences for criminals. Kaszak’s campaign manager was Chris Mather, who would become Emanuel’s communications chief during his run for mayor. Responding to Emanuel’s line of attacks, Mather told the Chicago Tribune, “Anyone can take a vote or two out of context, out of thousands of votes taken, and try to distort someone’s record. . . . Rahm is an opposition researcher at heart and this is the type of negative thing you’re going to get from that type of individual.”28

One endorsement Emanuel failed to get might have stung: his old employer the Illinois Public Action Council decided to endorse Kaszak. At the time Emanuel worked there, researcher and strategist Don Wiener worked for Citizen Action, the national group with which the council was affiliated. By 2002 Wiener was an Illinois Public Action Council board member. Wiener had been a leader of the grassroots national labor and community coalition opposing NAFTA when Emanuel shepherded it through during Clinton’s presidency. He had promised to help secure the council’s endorsement for Kaszak before Emanuel entered the race. Outside the Illinois Public Action Council board meeting where Emanuel made his pitch for endorsement, Wiener remembered him saying breezily, “Wiener, you’re wearing the same clothes you were wearing last time I saw you”—which may have been more or less accurate, because Wiener was wearing his trademark jeans and leather jacket. Emanuel’s words could be seen as a friendly signifier of familiarity, but Wiener took it as an intentional and clever jab that “you’ve stayed in the same place—you’re still a community organizer—and look where I’ve gone.” “He’s a genius in insulting people,” Wiener said.29

A Slugfest and a Slur

In early February 2002, Bill Clinton came to Chicago to campaign for Emanuel. Clinton headlined a $100-a-ticket fundraiser at the Park West auditorium and a $1,000-per-person reception at a private lakefront home. At that point Emanuel had almost $1 million in his war chest, while Kaszak had less than $65,000.30 But Kaszak remained at least outwardly confident, saying, “The people of the Fifth Congressional District cannot be bought.”31

Kaszak was still hanging on to her lead in mid-February; one poll showed her ahead of Emanuel 33 percent to 18 percent.32 By early March, though, her lead had evaporated, and the two candidates were neck and neck. One poll found one in four voters still hadn’t made up their minds, and Emanuel led Kaszak by a statistically insignificant margin of 35 to 33 percent.33 A Chicago Sun-Times editorial called the race “a slugfest in the grand Chicago tradition, between grass-roots activist Kaszak and Washington insider Emanuel.”34

So Kaszak could hardly afford the gaffe that occurred just two weeks before the election. Casimir Pulaski Day should have been a good one for Kaszak. It is an annual holiday commemorating the Polish-born Revolutionary War hero, usually celebrated with fairs and official events in Chicago’s Polish neighborhoods. Ed Moskal, president of the Polish American Congress community group, ardently wanted Kaszak to win the seat. So Moskal presumably thought he was helping when he declared at a Pulaski Day event that Emanuel was an Israeli citizen who had served two years in the Israeli army. He took things even farther, decrying Polish American Emanuel supporters by saying, “Sadly, there are those among us who will accept thirty pieces of silver to betray Polonia.”35

Both statements about Emanuel were false, and Moskal’s address was viewed as virulently anti-Semitic, eliciting condemnations from Jewish groups.36 Kaszak was in the crowd but didn’t immediately comment; she later said she had been distracted and didn’t hear much. Once she heard the full remarks, she denounced the speech and demanded Moskal apologize. He refused.37

Emanuel called Moskal’s statements “deplorable,” and he accused Moskal of orchestrating an anti-Semitic “whispering campaign” with Kaszak’s knowledge and tacit support.38 A spokesman for the Polish National Alliance made things worse by trying to justify Moskal’s comments, saying they were just “born of frustration with Jews.”39

The day after the festival the Emanuel campaign hosted a press conference of religious leaders to denounce Moskal’s statements. A desperate Kaszak showed up pleading to make her case. Emanuel campaign staff reportedly tried to prevent her from speaking, even calling an abrupt premature end to the press conference. Eventually Kaszak was able to address the assembled reporters, and she again decried Moskal’s remarks and said she and Emanuel were united in the cause of fighting anti-Semitism.40

Chicago Sun-Times political expert Lynn Sweet called Kaszak’s crashing the press conference “a high-stakes strategy that would take nerves of steel to execute.” Not only did it create an awkward moment; it risked alienating members of Kaszak’s Polish American base.41

The Emanuel camp’s original plan for the day had been to announce his endorsement by SEIU Local 1, the large and powerful union representing janitors, security guards, and other workers hired by private companies at city buildings. The planned endorsement statement by union president Tom Balanoff, a legendary Chicago labor leader, got drowned out by the excitement around the anti-Semitic remarks. A decade later Balanoff would become one of Emanuel’s prime adversaries, spearheading a campaign to brand him a “job killer.”

Kaszak ultimately lost by a wide margin, with the anti-Semitic remarks possibly playing a significant role, compounded by the impact of Emanuel’s copious campaign funds and hardball tactics. Emanuel took 50 percent of the vote in the field of six, compared to Kaszak’s 39 percent.42 Emanuel’s strongest showings came in two wards where his father had long practiced as a well-liked pediatrician—some voters had surely been treated by him in their childhood. Kaszak won in the most heavily Polish areas, but Emanuel beat her among Catholics as a whole and among Italian Americans and Irish Americans.43 In other words, a Jewish candidate framed as an elitist outsider nonetheless won over the heart of ethnic middle-class Chicago.

The Fifth District is heavily Democratic, so after the primary the general election’s outcome was nearly a foregone conclusion.44 Emanuel got 69.3 percent of the final vote, compared to 26.3 percent for Republican candidate Mark Augusti, a bank executive and tax reform activist.45

Clout Counted

A few years later, details emerged about some of the “volunteers” who had helped Emanuel defeat Kaszak. In 2005 federal prosecutors indicted more than thirty city employees on fraud and corruption charges in a scandal dubbed “Hired Truck.” Federal prosecutors alleged that city officials had taken bribes to steer city business to private trucking firms, which often did very little work, and that city officials had violated a longstanding court order known as the Shakman Decree, which barred patronage hiring—essentially the doling out of jobs for political reasons.46

Emanuel’s name came up numerous times in the proceedings: many city workers allegedly spent time campaigning for him, in anticipation of raises, promotions, or other rewards, or simply to keep their jobs. Chicago Tribune columnist John Kass referred to an “illegal patronage army of hundreds of workers” pounding the pavement for Emanuel, many of them led by water department top deputy Donald Tomczak, who pleaded guilty to bribery charges in the investigation.47 Kass coined a new nickname for Emanuel: “U.S. Representative Rahm Emanuel (D-Tomczak).”48

The Tribune quoted a retired Streets and Sanitation worker saying, “Daley made [Emanuel] a personal project. . . . Up until that time, I had never heard of Rahm Emanuel, but the Daley forces at City Hall said, ‘We are going to support him,’ so we did.”49

Daniel Katalinic, the deputy Streets and Sanitation commissioner, told prosecutors that he organized a “white ethnic” patronage army of hundreds to work on campaigns for Emanuel and other candidates backed by Daley; and that he had met with patronage director Robert Sorich at Emanuel’s campaign headquarters to set up work squads.50 Names of workers who had volunteered for Emanuel’s 2006 congressional reelection campaign also came up on a secret “clout list” of city employees earmarked for promotions and raises.51

Emanuel said that he had never met Katalinic and had no idea anything illegal was going on amid the thousands of people who had volunteered for his campaign.52 Prosecutors never said Emanuel himself had done anything wrong. But the investigation highlighted that although his image was more Washington than Bridgeport, more pinstripes than patronage, Emanuel was still firmly entrenched in the Chicago Democratic Machine.

A DLC Democrat

The congressional seat was Emanuel’s first elected position, even after more than a decade as a top politico. He was a consummate example of the “new Democrat,” or “DLC Democrat.” The acronym refers to the Democratic Leadership Council, a nonprofit organization founded in 1985 to move the Democratic Party away from its populist, left-leaning stances of the 1960s and ’70s. The most prominent DLC chairman was Bill Clinton himself, who took the helm in 1990. And President Clinton’s anti-crime, welfare reform and free trade initiatives—undertaken with Emanuel’s help—epitomized the DLC political philosophy.53

In a January 1, 2001, document, the DLC described its “New Democrat Credo”:

In keeping with our party’s grand tradition, we reaffirm Jefferson’s belief in individual liberty and capacity for self-government. We endorse Jackson’s credo of equal opportunity for all, special privileges for none. We embrace Roosevelt’s thirst for innovation and Kennedy’s summons to civic duty. And we intend to carry on Clinton’s insistence upon new means to achieve progressive ideals. We believe that the promise of America is equal opportunity for all and special privilege for none. We believe that economic growth generated in the private sector is the prerequisite for opportunity, and that government’s role is to promote growth and to equip Americans with the tools they need to prosper in the New Economy.54

Reading between the lines, the DLC philosophy supported scaling back the role of government while emphasizing the principles of personal responsibility, liberty, and self-help. It proposed the private sector as key to helping people break their dependence on the government and pull themselves out of need and poverty. And it strongly advocated for charter schools and free trade agreements.55 The DLC dissolved in 2011 after a failed attempt to recast itself as more of a think tank.56 It had been struggling with identity and influence issues going back at least to the mid-2000s, when more liberal influences, including the “net-roots” movement Moveon.org, battled for power with the party’s free-market moderates.57

But even after the council’s demise, DLC philosophies would live on. Emanuel would be joined by other politicians with close links to the DLC in the Obama administration: Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, White House economic adviser Lawrence Summers, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, and Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano, among others.58

Emanuel would also carry the DLC philosophical torch into Chicago City Hall.

Lakes, Vets, and Victims

Even as a quintessential DLC Democrat, Emanuel sponsored many bills in Congress that were attractive by progressive or liberal standards. The Billionaire’s Loophole Elimination Act made it harder for wealthy people in bankruptcy proceedings to hide their assets. Another bill funded electronic monitoring of adult sex offenders. The Great Lakes Restoration Act, hailed by environmental groups, provided a comprehensive framework for reducing pollution, combating invasive species, restoring degraded areas, and increasing community access to the lakes. One bill facilitated health insurance coverage for kids; another reined in unscrupulous life insurance agents targeting members of the military. The Welcome Home G.I. bill extended educational benefits for military members. Another bill allowed victims of Hurricane Katrina to get Earned Income Tax Credit payments earlier than usual. And yet another bill increased the tax credit for alternative fuel vehicles assembled in the United States.59

The nonpartisan project Govtrack.us, which tracks legislative data and trends online, described Emanuel as a “rank-and-file Democrat” based on his voting record. The website ranks legislators on leadership and ideology, in high-to-low and liberal-to-conservative continuums, respectively. Emanuel came in almost dead center among Democrats on ideology, and he ranked in the upper quarter on leadership compared to legislators of both parties. The leadership mark is based on rates of mutual bill cosponsorship—“It’s a little like if you scratch my back will I scratch yours?” explains the group’s website.60 In other words, Emanuel was willing to play ball to get what he wanted.

The website OnTheIssues.org compiles highlights of legislators’ voting records and scorecards from various organizations. Emanuel gained perfect or near-perfect marks for his records on reproductive rights, gay rights, and environmental issues. He got an 87 percent approval rating from the AFL-CIO and 100 percent from the National Education Association union, albeit both from December 2003, after less than a year in office. Overall his voting record indicated support for clean energy; a relatively tough approach to the oil and gas industry; a mixed bag on civil liberties, war, and national security issues; and strong support for free trade, though he did vote against the controversial Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), a sort of stepsister to NAFTA.61

Emanuel got extremely negative marks from anti-immigration groups for his congressional voting record; they saw him as staunchly pro-immigrant. He cosponsored immigration reform without amnesty for undocumented residents, an approach often opposed by both pro-immigrant and anti-immigrant forces. He voted against constructing a wall on the Mexican border and against forcing hospitals to collect information on undocumented immigrants.62 Like most Democrats, he also voted no on the most notorious piece of federal immigration-related legislation in recent history: the Border Protection, Anti-terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act (HR 4437), introduced in December 2005 by Wisconsin Republican congressman James Sensenbrenner.63

The draconian anti-immigrant bill would have criminalized a broad range of everyday interactions with undocumented immigrants. It would theoretically have made teachers, counselors, doctors, landlords, and other everyday people into criminals just for giving undocumented immigrants a ride, renting them a room, or providing them health or social services.64 The House passed the bill 239 to 182 on December 16, 2005. In response, immigrants and their supporters marched by the tens of thousands in cities nationwide. The movement started right in Emanuel’s hometown of Chicago, with the first march of more than one hundred thousand taking the nation by surprise on March 10, 2006.65

Democratic leaders, including Chicago congressman Luis Gutierrez and Mayor Daley, denounced the Sensenbrenner bill and joined immigrants’ rights demonstrations. Many of Emanuel’s Polish, Latino, and other immigrant constituents were among the marchers.

But in a 2010 speech during the Chicago mayoral campaign, Gutierrez said Emanuel put politics before immigrants’ rights during the seminal fight. “Here’s a fact Rahm doesn’t want you to know but one he can’t escape from,” said Gutierrez, who was backing Emanuel’s opponent Gery Chico in the mayoral race. “When the Sensenbrenner bill was on the floor of the House of Representatives, as chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, Rahm Emanuel told his colleagues to support Sensenbrenner. He told targeted Democrats in tough re-election fights that he wanted them to vote for this anti-immigrant bill. That’s a fact, an irrefutable fact. . . . When he had a chance to step up as a leading member of Congress and do the right thing instead of the political thing, he refused to do it.”66

Emanuel’s votes often upset progressive, African American, and Latino elected officials and constituents. He voted 128 times against bills or amendments supported by a majority of the ethnic minority members of the Congressional delegation from Chicago, according to a report circulated by former Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun, who competed against Emanuel during the Chicago mayoral race.67 Many of those bills were backed by the Congressional Black Caucus and Chicago congressmen Danny K. Davis, Bobby Rush, and Jesse Jackson Jr.68 A number of the bills involved free trade agreements, including those with Singapore, Peru, Chile, and Morocco; Emanuel voted in favor of free trade, while African American congressmen and unions opposed the agreements because of concerns about their impact on US jobs.69 Many of the contentious votes had to do with defense: Rush, Jackson, and Davis tended to take antiwar stances; but Emanuel supported defense spending, military options regarding Iran, and a resolution affirming that the world was safer without deposed Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.70 Emanuel also voted to make provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act permanent—to the outrage of civil liberties groups, which denounced the act for allowing unwarranted spying in the name of the war on terror.71

It was not clear what Emanuel’s own thoughts were about the war in Iraq. He took office after the initial vote to authorize the invasion, but during his congressional campaign he indicated he would have voted in favor of military intervention.72 As a congressman he was relatively cagey about the increasingly unpopular conflict, a stance that came through during his January 2005 appearance on NBC’s Meet the Press. Emanuel didn’t definitively answer host Tim Russert’s questions about whether he would have voted to invade Iraq knowing there were no weapons of mass destruction. He said, “I still believe that getting rid of Saddam Hussein was the right thing to do, OK?”73

Reclaiming the House

In 2004, after the death of former chair Bob Matsui, Emanuel became chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.74 Founded in the mid-1800s, the DCCC is the official campaign arm of Democrats in the House of Representatives, a well-funded organization with a large research staff expert in Emanuel’s early forte, opposition research.75

Republicans had controlled the House since the “Republican Revolution” of 1994, featuring Georgia Congressman Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America.”76 Emanuel’s major goal as head of the DCCC was to reclaim the House for Democrats in the 2006 midterm elections. It was a major challenge: in January 2006, the House had 231 Republican members and just 201 Democrats (plus one Democratic-leaning independent), and Republican George W. Bush was in the White House.77

Emanuel pulled it off.

Several books and documentaries describe a strategically brilliant operation showcasing Emanuel’s cutthroat style and stellar fundraising ability. Chicago Tribune reporter Naftali Bendavid’s book The Thumpin’ described Emanuel masterfully juggling the campaigns of candidates nationwide, down to the smallest minutiae. Candidates rose and fell in his favor based on their shifting political prospects.

That year Emanuel also released his book The Plan: Big Ideas for America, written with fellow Clinton aide and DLC president Bruce Reed.78The Plan outlined their political philosophy and their vision for “a new social contract.” The authors indicated that politics should be driven by ideals rather than cynical pragmatism, denouncing Democrats who “bought into [Republican strategist] Karl Rove’s logic that the most important challenge of our time is how to win an election.” They decried a party driven by focus groups, consultants, and “second opinions,” swaying without an ideological rudder.79

Ironically, the approach condemned in The Plan is very similar to what fans and critics alike describe as Emanuel’s own approach to politics. A prime example would be the 2006 campaigns, where Emanuel pushed candidates to win at all costs. “He had no interest in a Democratic Party that was purer than the opposition if it lost,” Bendavid wrote. “He did not care where a candidate stood on abortion or the Iraq war, or whether that candidate was displacing a ‘better’ Democrat, if such purity cost a House seat.”80

Money had always been central to Emanuel’s political strategy, and as the 2006 midterms geared up, he was only interested in candidates who could raise buckets of it. In their book Winner-Take-All Politics, political scientists Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson noted:

Emanuel spent more of his time courting cash than doing anything else. No matter how attractive a candidate or appealing his message, it meant little if he could not advertise on television, print brochures, or pay campaign workers to knock on doors. . . . In the 2006 campaign, Emanuel and his staff were judging candidates almost exclusively by how much money they raised. If a candidate proved a good fund-raiser, the DCCC would provide support, advertising, strategic advice, and whatever other help was needed. If not, the committee would shut him out. . . . Most of Emanuel’s fund-raising time was spent meeting with wealthy lawyers or financiers, telling them this was the year to give.81

One of the hot seats up for grabs in the 2006 race was Illinois’s Sixth District. The district, which enfolds Chicago’s western suburbs, was 78 percent white; relatively well off, with a $65,000 median household income; and politically moderate.82 In both 2000 and 2004, 53 percent of voters had chosen George W. Bush for president.83

Since 1975 the Sixth District had been represented by Henry Hyde, a right-wing Republican who took a lead role in the effort to impeach President Clinton over the Monica Lewinsky affair.84 In the 2004 election, a likable software worker and community activist named Christine Cegelis made a decent showing against Hyde, getting 44 percent of the vote.85 The eighty-one-year-old Hyde planned to retire after his term ended, so the 2006 race seemed ripe for Cegelis, a political outsider who could relate to the struggles of everyday people. She had campaigned for liberals Hubert Humphrey and George McGovern in her youth and got back into politics decades later as she saw her family and neighbors losing jobs and struggling to afford medicine. She opposed CAFTA and called for a rational timetable for withdrawal from Iraq. She had enthusiastic backing from high-profile left-leaning Democratic groups, bloggers, and leaders, including Democratic National Committee chair Howard Dean and the Independent Voters of Illinois-Independent Precinct Organization (IVI-IPO). She also had significant support among local residents.86

Photo by Staff Sergeant Jon Soucy, US Army.

During the 2006 midterm elections, Congressman Emanuel backed candidates with military backgrounds—including veteran Major Tammy Duckworth (above), whom he supported over a popular union-backed community activist.

But rather than backing Cegelis, Emanuel recruited Tammy Duckworth, who didn’t actually live in the Sixth District. Duckworth was a veteran who had lost both her legs and had her right arm shattered in Iraq in 2004, when her helicopter was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade north of Baghdad. She was an impressive and sympathetic figure, determined not to be held back by her devastating injury. She came across as articulate, cheerful, and accessible. “Duckworth—bespectacled, wearing an American flag on her lapel, her dark hair streaked with blond—was one of Emanuel’s dream candidates,” wrote Bendavid.87

Duckworth said the war was a mistake, but she stressed support for her military brethren and the idea that the United States must stay the course in Iraq. Cegelis and her supporters were at first shocked and then disillusioned when they learned that the Democratic Party was abandoning them for Duckworth.88

With Emanuel’s backing, Duckworth earned the support of elected officials including Senators Dick Durbin and John Kerry and Congressman Mike Honda of California, who, like Duckworth, was Asian American. Barack Obama, then the junior senator from Illinois, also campaigned for Duckworth. The Illinois AFL-CIO endorsed her, though only Cegelis had been a union member—as a telephone operator with the Communications Workers of America.89

“It was an offensive outrage for Clinton, Kerry, Obama and other Senate Democrat insiders to foist Duckworth on the Sixth District, when they had a tough, strong campaigner in Cegelis,” opined Philadelphia-based Daily Kos pundit Rob Kall.90

Despite all the big-time money and endorsements, Duckworth beat Cegelis in the Democratic primary by only 4 percent. Bitter, Cegelis didn’t publicly concede until Duckworth called her, and she didn’t endorse Duckworth for two weeks. Emanuel gloated that “we took on the Communists in the party,” though in reality Cegelis’s supporters were mostly regular residents who saw Cegelis as one of their own.91

In the general election Duckworth lost by two percentage points, or 4,810 votes, to Republican Peter Roskam.92 The loss came despite the fact that Duckworth’s campaign had raised $4.56 million, compared to Roskam’s $3.44 million. (Cegelis, by contrast, had raised only $363,000 for the primary race.)93

Throughout the 2006 campaigns Emanuel had high-profile clashes with DNC chair Howard Dean, a former Vermont governor and doctor whose run for the presidency in 2004 had been propelled largely by his strong antiwar stance and pioneering online strategy. Dean criticized Emanuel for failing to back liberal and popular candidates like Cegelis. Meanwhile, Emanuel excoriated Dean for failing to put up more money for the races, especially because Republicans were greatly outspending Democrats overall. Emanuel demanded that Dean lay out $100,000 for each of forty key races in 2006, while Dean was more focused on a long-term strategy of building a Democratic base in all fifty states. Details of the leaders’ conflict were leaked to the press, and Dean supporters surmised that Emanuel was conniving to make sure Dean took the blame if Democrats did not reclaim the House.94

A few of the DCCC’s favored candidates were defeated in the Democratic primaries by opponents with genuine grassroots support and clear antiwar positions, who went on to defeat Republicans in the general election. In New Hampshire, Carol Shea-Porter, a social worker and community college teacher, won the primary by almost twenty percentage points, even though the DCCC had funded the campaign of moderate State House minority leader Jim Craig.95 In the general election, Shea-Porter beat Republican incumbent Jeb Bradley by almost 3 percent.96 Similarly, in New York’s Hudson Valley, the DCCC eschewed John Hall—an environmental activist and former lead singer of the 1970s band Orleans—in favor of attorney Judy Aydelott, a former Republican and skilled fundraiser.97 Hall got almost double Aydelott’s votes in the primary and then won the general election to take the seat.98

Ultimately Democrats won the House in a near-landslide, ending up with 233 seats to Republicans’ 202. They also retook the Senate, 51 to 49. California congresswoman Nancy Pelosi became the first female Speaker of the House.99 Emanuel celebrated in typical fashion, jumping on a table and telling the crowd that Republicans “can go fuck themselves!”100

The Bailout

Like most congressmen, Emanuel didn’t face serious challenges to reelection once he was an incumbent, but donors still contributed generously to his campaign fund. He raised just shy of $9 million during his three-term congressional tenure. The political transparency organization Opensecrets.org listed the companies with which major donations were affiliated. (Donations didn’t come from the companies themselves but rather from political action committees, employees, owners, their immediate family members, and others connected to the companies).101 Madison Dearborn Partners, a Chicago-based private equity firm specializing in buyouts, topped the list. Next was the phone company AT&T, followed by the Swiss-headquartered global financial services company UBS AG, and then the New York–based global investment firm Goldman Sachs. Fifth on the list of donors was Emanuel’s old employer Dresdner, Kleinwort & Wasserstein (the investment bank had changed its name from Wasserstein Perella and Company following a 2001 buyout by the German Dresdner Bank).102

Over the course of Emanuel’s congressional career, the top five industries from which he received money were securities and investment ($1.7 million), lawyers ($756,768), the entertainment industry ($481,864), real estate ($370,460), and commercial banks ($265,500). Pro-Israel groups donated $169,700, and public sector unions—which would become his nemesis as mayor—donated $176,500. Other unions donated $109,500. Emanuel was consistently the first or second top recipient of donations from hedge funds and private equity firms for the entire House of Representatives.103 He held seats on both the Ways and Means and Financial Services committees, positions of much interest to the financial sector.104

The year that turned out to be Emanuel’s last in Congress featured legislation that showcased his deep ties to the financial sector. He played a key role in orchestrating and building political support for the controversial $700 billion bailout of banks and financial institutions including Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and JPMorgan Chase, meant to prevent a total economic collapse and free up credit to stimulate spending and rescue home mortgages in the seizing-up economy.105

On October 3, 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act passed the House of Representatives 263 to 171, with Emanuel among the 172 Democrats voting for it.106 Four days earlier, the bailout bill had failed in the House; as the Democratic Caucus chair (and fourth-ranking congressman), Emanuel played an important role in getting fifty-eight congressmen, including thirty-three Democrats, to change their votes. 107

In the months and even years following the bank bailout, the public was largely furious with the maneuver and how it was carried out. Executives at many of the bailed-out institutions continued to give themselves multimillion-dollar bonuses and raises, and meanwhile the bailout did not result in notably increased lending or mortgage relief for regular people.108 The anger over the bailout helped spark a major shift in public consciousness, a sudden spike in the awareness of class, and the concepts of “Main Street versus Wall Street” and “the 99 percent.” It also motivated the rise of the virulently antigovernment Tea Party movement.109

“In no uncertain terms, our leaders told us anything short of saving these insolvent banks would result in a depression to the American public,” said Josh Brown, a Manhattan investment adviser turned industry critic, on public radio’s Marketplace Money in 2011. “We had to do it! At our darkest hour, we gave these banks every single thing they asked for. . . . We bailed out Wall Street to avoid Depression, but three years later, millions of Americans are in a living hell. This is why they’re enraged, this is why they’re assembling, this is why they hate you. Why for the first time in fifty years, the people are coming out in the streets and they’re saying, ‘Enough.’”110

Though Emanuel was about to leave Congress, this new paradigm would be a defining factor of his tenure in the Obama White House and even more directly in Chicago’s City Hall.