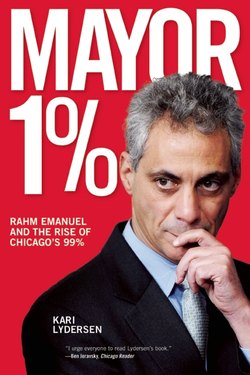

Читать книгу Mayor 1% - Kari Lydersen - Страница 9

Оглавление1

A Golden Boy

Rahm Emanuel was born in Chicago on November 29, 1959. His family story was one of the many quintessential American Dream tales for which Chicago is famous—first- and second-generation immigrants making good through hard work, pluck, and family and community connections.

Rahm’s father, Benjamin Emanuel, was born in Jerusalem to Russian émigrés. During the struggle for independence that culminated with the founding of the state of Israel in 1948, he was active in the Irgun Zvai Leumi, a far-right-wing Zionist paramilitary organization widely described as “terrorist” for carrying out assassinations and attacks on Palestinians and the British, whom they viewed as illegally occupying Israel. The group bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in 1946, killing ninety-one people. Members killed at least two hundred Arabs during the 1930s and 1940s in multiple attacks, including bombings and shootings. And in 1948 Irgun commandos carried out the Deir Yassin massacre, in which more than a hundred Palestinians in the small village were killed, including a group of men who were executed in a stone quarry.1

Benjamin’s family adopted the surname Emanuel in the 1930s to honor Benjamin’s brother Emanuel Auerbach, who had been killed in the 1930s in an Arab uprising.2 Young Benjamin went to Czechoslovakia—he had been studying in Switzerland—in a failed attempt to smuggle guns to the Zionist underground. And he was reportedly bashed on the head by a British soldier’s baton so forcefully that it left a permanent dent in his skull.3 Author Jonathan Alter described Benjamin as a “Sabra”: the term, derived from the Hebrew word for prickly pear cactus, is used to describe native-born Israelis, and also denotes “abrupt and aggressive” personalities that could “mask sensitive souls.”4

Benjamin came to Chicago in 1953 for medical training at Mount Sinai Hospital on the West Side, where he met an X-ray technician named Marsha Smulevitz. She was the daughter of a Romanian from Moldova who had fled pogroms and arrived in the United States alone in 1917, at the age of thirteen. Marsha’s father, Herman, made a living as a steelworker, truck driver, and meat cutter, and was known as a labor organizer and self-taught intellectual.5 Smulevitz grew up to be a civil rights activist as well; she later served as a chapter chair of the Congress of Racial Equality. At one point she also owned a North Side club that featured live rock music. She later became a psychotherapist, and was still practicing when her son became mayor of Chicago.6

Photo by Kari Lydersen.

The Emanuels lived in Uptown, a diverse, somewhat hardscrabble North Side neighborhood, before moving to tony Wilmette.

Benjamin and Marsha married in 1955 and lived for a time in Israel before returning to Chicago, where Benjamin built his pediatrics practice into one of the city’s largest.7 Their three sons—Ezekiel (Zeke), Rahm, and Ariel (Ari)—were an energetic, competitive, and gifted bunch from early on, and the three boys would all reach pinnacles in their professions. Zeke, two years older than Rahm, became a nationally prominent oncologist and medical ethicist; he served as a department chair of bioethics at the National Institutes of Health and played a role in President Barack Obama’s health-care reform legislation, carried out while Rahm was White House chief of staff. Ari, a year younger than Rahm, became a famous talent agent widely known as the inspiration for foul-mouthed, hard-charging Ari Gold on the HBO show Entourage. And Rahm, of course, became a prominent political operative, elected official, and fundraiser who, like Ari, was also graced with a prime-time TV alter ego: the impatient, arrogant, and profane White House chief of staff Josh Lyman on the political drama The West Wing.8

In a 1997 New York Times profile, Elisabeth Bumiller wrote, “Of the three brothers, Rahm is the most famous, Ari is the richest and Zeke, over time, will probably be the most important. Zeke is also, according to his brothers, the smartest. Rahm, naturally, gets the most press attention. . . . All are rising stars in three of America’s most high-profile and combative professions. All understand and enjoy power, and know how using it behind the scenes can change the way people think, live and die.”9

The boys spent summers in Israel, where they learned to speak Hebrew. They also attended civil rights protests with their mother. Until Rahm was seven or eight, the Emanuel family lived in an apartment in Uptown, a diverse, somewhat hardscrabble neighborhood near the lake on Chicago’s North Side. The boys attended a Jewish day school and spent long hours together riding bikes and hanging out at the nearby Foster Avenue beach.10 They often had to defend themselves against kids who picked on them because they were Jewish or even because they mistook Rahm—with his curly dark hair and deep tan—for an African American.11 The Emanuels were plenty able to defend themselves; roughhousing and wrestling were a way of life for the rowdy and competitive boys, as Zeke later described in a memoir.12 Rahm was literally born into this atmosphere: Zeke described how he and a cousin played a game called “bounce the baby,” in which they jumped on a sofa bed “like a couple of jackhammers” and tried to knock infant Rahm—“Rahmy,” as Marsha called him—onto the floor.13

The boys all took ballet lessons, and young Rahm was known to pirouette around the house. He studied at the Joel Hall Dance Center in Chicago and became a talented dancer; he was even offered a scholarship to the acclaimed Joffrey Ballet at age seventeen. Decades later the nickname “Tiny Dancer” still stuck with Emanuel, whose five-foot-seven stature surprises many in light of his outsize personality.14

Growing Up

In 1967 the Emanuels moved to Wilmette, a lavishly wealthy lakefront suburb north of Chicago, where the median household income in 2010 was more than $100,000 a year and only about 1 percent of the population was African American.15 The Emanuels lived in one of the more modest homes, not a sprawling mansion. But the boys attended New Trier Township High School, iconic as one of the nation’s most elite public high schools, with academic, athletic, and extracurricular programs and facilities worthy of a university.16 In his 1991 book Savage Inequalities, Jonathan Kozol contrasted the lush, privileged atmosphere of New Trier with impoverished public schools in East St. Louis, Illinois—driving home the message of two racially and economically separate Americas. NBC Chicago blogger Edward McClelland noted that “there’s something about New Trier Township that ignites class resentment. It’s a symbol of elite education, a finishing school for the sort of young people most of us only met by watching Risky Business or Mean Girls.”17

The Emanuel family was close-knit and kept its history of migration and flight from persecution very much alive. The walls were lined with photos of relatives, including some who had perished in the Holocaust. Grandparents, an uncle, and a cousin lived with them for periods of time, and stories of family travails and triumphs were told and retold.18

When the boys were teenagers, the family adopted an eight-day-old girl named Shoshana. Benjamin had given the infant a checkup and found she’d suffered a brain hemorrhage at birth. According to Bumiller’s profile, the girl’s Polish Catholic mother pleaded with him to help find a home for the baby, and after a week of debate the Emanuels decided to take the ailing child in themselves. Shoshana needed extensive surgery and physical therapy, and her childhood was reportedly full of emotional and physical struggles. After graduating from New Trier, she had what has been described as a difficult life, including unemployment and single motherhood, with Marsha later raising her two children.19

Writer and editor Alan Goldsher, who grew up near the family in Wilmette, later published a revealing reminiscence about the Emanuel household. In a 2012 story for the Jewish Daily Forward, he described Benjamin Emanuel, “aka Dr. Benny,” as “a faux-crotchety alpha male, the proverbial grump with a heart of gold, the kind of person who would offer to administer allergy shots at his home rather than at his office, just because it was difficult for the patient’s working mother to get her son to said office before closing time.”20

Goldsher had to stay long enough to make sure he didn’t have a bad reaction to the medication, and this usually meant hanging out in the Emanuels’ backyard. “Generally, my sojourns behind the house were solitary and unexciting,” he wrote.

But every once in a while, Dr. Benny’s two high school aged sons paid me a visit. It was common knowledge around Wilmette that Rahm and Ari Emanuel were bullies—hyper-intelligent bullies, but bullies nonetheless. (This was unlike their father, who only pretended to be a bully.) Rahm and Ari were, respectively, six and five years older than I was, so other than my weekly appearances at Dr. Benny’s, our paths never crossed; still, in those brief moments, the boys took a disliking to little ol’ me. How do I know they disliked me? Because at every given opportunity, they threw me to the ground. Hard. Really hard. I’ve blocked out the specifics of the attacks. The only things I know for certain were that a) they were unprovoked, and b) they hurt.21

Other reports have described the Emanuel household as a place of constant philosophical and political debate and one-upmanship, with the brothers competing intensely. Zeke described his parents lovingly but firmly pushing the boys to do better in sports and school. Their father taught them to play chess: “He would admonish us with two messages: ‘Think three moves ahead!’ and ‘Remember what Napoleon said: “Offense is the best defense,”’” Zeke wrote.22

One can speculate that it was a rarified atmosphere of mutual self-confidence, based on liberal social values yet permeated with a sense of insular superiority. Bumiller’s profile quoted Ari: “The pressure is that you were judged by the family. . . . Our family never cared about the kid down the block.”23

Rahm was introduced to Democratic politics early on; as teenagers he and Ari joined their mother in volunteering for the successful congressional campaign of Abner Mikva, a popular liberal who later served as a federal chief judge and White House counsel.24

Despite the intellectual rigor of the Emanuel home, Rahm was an unexceptional student; a guidance counselor suggested he might consider other options besides college. (Ari, who is dyslexic, also struggled with schoolwork.)25 Rahm had an after-school job at Arby’s that ended up endangering his life and left him with one of his most celebrated physical characteristics. As a teenager he cut his finger at work and then took a late-night swim in Lake Michigan after the high school prom. The result was a life-threatening gangrenous infection, many weeks in the hospital, and the partial amputation of his middle finger.26 Given his proclivity for literally or verbally giving people the finger, Emanuel’s severed digit would become a lifelong source of amusement. President Obama would later joke that the accident left Emanuel “practically mute.”27

The Education of Rahm Emanuel

After high school graduation—having turned down the Joffrey Ballet scholarship—Emanuel headed to Sarah Lawrence College, a small and exclusive liberal arts school (formerly a women’s college) north of New York City.28Emanuel studied dance, philosophy, and other social sciences at Sarah Lawrence, and he became heavily involved in politics.29

At age twenty he took a semester off to volunteer for the congressional campaign of Illinois Democrat David Robinson, who was seeking to unseat Paul Findley, a Republican viewed as unsympathetic to Israel because of his support for Palestinian rights.30 Forrest Claypool—a lifelong Chicago politician who also worked for Robinson—told Chicago Magazine that this was the first prominent national campaign to use an opponent’s purported anti-Israel stance as a major hook for fundraising.31

Emanuel started out volunteering as Robinson’s driver, but he soon became the campaign’s fundraising director.32 He helped Robinson raise $750,000, and though the candidate ultimately lost the race, young Emanuel made an impression— notably on field director David Wilhelm, who later managed Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign and became the youngest chair of the Democratic National Committee.33

After graduating from Sarah Lawrence, Emanuel worked for the Illinois Public Action Council, a large consumer advocacy group known for sending staff door to door to raise funds and enlist support for progressive causes. The council endorsed candidates and spent money on independent campaigns backing them. At the time Emanuel worked there, the council’s program director was Jan Schakowsky, who would later become a long-serving congresswoman representing North Side “lakefront liberals” and the wealthy North Shore suburbs beyond.”34

Emanuel also did fundraising work for Paul Simon’s successful 1984 US Senate campaign, helping the liberal upset a three-term Republican incumbent. Though Emanuel was just twenty-four, famed Democratic strategist David Axelrod would later say, his tenaciousness and success in wringing money out of donors was striking.35

In the mid-1980s California congressman Tony Coelho was chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), the campaign arm of Democrats in the House of Representatives. On a trip to Illinois he met Emanuel, who was working at the Illinois Public Action Council. Coelho was immediately impressed by the young politico, who he said “was organized, bang-bang-bang, knew the pros and cons” of every race. He recruited Emanuel to join the DCCC.36

Emanuel headed to Washington with the committee, then returned to Chicago to set up the DCCC’s Midwest office, and he was named the committee’s national campaign director for the 1988 elections.37 While at the DCCC Emanuel notoriously sent a dead fish in the mail to pollster Alan Secrest, whose work he blamed for the loss of a congressional seat in Buffalo, New York. Secrest responded with a six-page letter excoriating Emanuel for arrogance, “lying,” “star-fucking,” and “hubris.” Emanuel proceeded to fax the letter out to journalists and colleagues, very possibly to build his own reputation as someone not to be messed with.38

From 1984 to 1985 Emanuel earned a master’s degree in communications at Northwestern University. He lived on the Evanston campus, not far from his parents’ Wilmette home, and he impressed his fellow graduate students with his political rather than academic ambitions and his ceaseless appetite for lively debate.39 His communications colleagues later speculated that Northwestern was where Emanuel learned the rhetorical techniques that helped him avoid answering tough questions from reporters and critics—for example, by taking a concrete question in a theoretical direction or answering a question about the past with a proclamation about the future.40

Becoming Rahmbo

Harold Washington’s election as mayor of Chicago in 1983 was a euphoric moment for many Chicagoans. A coalition of African Americans, whites, and Latinos came together to elect the independent African American congressman, who ran a massive grassroots campaign that registered more than one hundred thousand new African American voters.41 Once in office Washington kept the momentum going, filling city agencies with progressive and multiracial staff; starting the city’s first environmental affairs department; and striving to address economic, social, and environmental injustice in various forms. It wasn’t easy—his tenure was characterized by the infamous “Council Wars.” Washington backers in City Council constantly squared off against old-regime loyalists headed by Alderman Edward Vrdolyak. Racial tension boiled, and Vrdolyak’s contingent blocked many of Washington’s appointees and initiatives. But even with the bitter political standoffs, many saw a “new Chicago” emerging, and hopes were high. Washington easily won re-election against Vrdolyak in April 1987. So it was a devastating blow for many when Washington died of a heart attack on November 25, 1987, at the age of sixty-five.42

Washington’s death cleared the way for the return of the Daley family, which would become a Chicago dynasty. In 1976 the twenty-one-year-term of Mayor Richard J. Daley had come to an end with the death of the “Boss,” also by heart attack. His son Richard M. Daley ran in the 1989 mayoral election to replace interim Mayor Eugene Sawyer, an African American alderman installed by City Council, whose tenure was also characterized by bitter racial hostilities.

Though still not even thirty years old, Emanuel was already blossoming as a shrewd and powerful political operative, and he likely knew that allying with Daley could be a crucial move for his own career. Ben Joravsky of the Chicago Reader speculated:

Emanuel was no dummy. He knew Daley would defeat Sawyer and, once in office, would probably rule for life—just like his father, the late Richard J. Daley. So Emanuel did what any bright and ambitious young politico would do—he signed on with Daley. By all accounts, he made himself indispensable to the boss as a fundraiser, badgering, bullying, or guilt-tripping the locals into giving money to Daley’s campaign. It was then that Emanuel established his reputation as Rahmbo—the brash, arrogant, and tempestuous assistant that political bosses use to get things done.43

Emanuel honed his aggressive fundraising tactics for Daley. Chicago Tribune reporter and author Naftali Bendavid noted that Emanuel “told one donor that if he was not prepared to donate a certain amount he should keep his money, and he slammed down the phone.” Apparently the approach worked: Emanuel raised $13 million in seven weeks for the man who would become Chicago’s longest-serving mayor, and whose office Emanuel would later claim.44