Читать книгу Mayor 1% - Kari Lydersen - Страница 7

ОглавлениеIntroduction

March 4, 2012, was Chicago’s 175th birthday, and the city celebrated with a public party at the Chicago History Museum. The event promised actors portraying famous Chicagoans including Jane Addams, founder of Hull House and advocate for immigrants, children, and factory workers. Little did the organizers know that the show would be stolen by a woman some viewed as a modern-day Jane Addams—more eccentric and irascible, less renowned and accomplished, but just as willing to raise her voice and speak up for the weak and vulnerable.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel grinned broadly as the Chicago Children’s Choir, dressed in red, sang a lively version of “Happy Birthday.”

He had reason to smile.

Ten months earlier he’d been inaugurated as leader of the nation’s third most-populous city, taking the reins from legendary Mayor Richard M. Daley. And while his term hadn’t been a cakewalk, so far things seemed to be going well. He had inherited a nearly $700 million budget deficit and attacked it with an aggressive round of cost-cutting and layoffs. The labor unions had resisted, but ultimately Emanuel was able to strike some deals and come out on top. Meanwhile, he was moving forward with his plans to institute a longer school day, a promise that had gained him positive attention nationwide. He was already assuming Daley’s mantle as the “Green Mayor”: in February he had announced that the city’s two coal-fired power plants would close, and miles of new bike lanes were in the works.

Emanuel had even snagged two important international gatherings for Chicago: the NATO and G8 summits, to be held concurrently in May 2012—the first time both would be hosted in the same US city.

There had been sit-ins and protests by community groups and unions related to the summits, school closings, and other issues. But Emanuel had shown a knack for avoiding and ignoring them, and so far he didn’t seem to have suffered too much political fallout.

As Emanuel watched the swaying, clapping singers at the birthday party, he didn’t seem to notice a crinkled orange paper banner bobbing in the crowd of revelers. It said, “History Will Judge Mayor 1 Percent Emanuel for Closing Mental Health Clinics.” He’d gotten the moniker early on in his tenure. As Occupy Wall Street–inspired protests swept the nation, it was a natural fit for a mayor known for his high-finance connections and brief but highly lucrative career as an investment banker.

A staffer for the mayor or the museum did notice the banner, and told the man holding it to put it away. Matt Ginsberg-Jaeckle, a lanky longtime activist, complied, partially folding the banner and lowering it into the crowd. The song ended, and Emanuel began shaking hands with the singers and other well-wishers near a colorful multitiered birthday cake.

Then a shrill, rough voice cut through the chatter, causing heads to turn as the orange banner was unfurled and raised again.

“Mayor Emanuel, please don’t close our clinics! We’re going to die. . . . There’s nowhere else to go. . . . Mayor Emanuel, please!” cried a woman with a soft, pale face, red hair peeking out from a floral head scarf, and dark circles around her wide eyes that gave her an almost girlish, vulnerable expression.

It was Helen Morley, a Chicago woman who had struggled all her life with mental illness but still managed to become a vocal advocate for herself and others in the public housing project where she lived, and for other Chicagoans suffering from disabilities and mental illness. For the past fifteen years she’d been a regular at the city’s mental health clinic in Beverly Morgan Park, a heavily Irish and African American, working- and middle-class area on the city’s Southwest Side. It was one of six mental health clinics that Emanuel planned to close as part of sweeping cuts in his inaugural budget. He said it made perfect economic sense—it would save $3 million, and the patients could move to the remaining six public clinics. But Morley and others pleaded that he didn’t understand the role these specific clinics played in their lives and the difficulty they would have traveling to other locations.

Morley’s eyes were fixed unblinkingly on the mayor as she walked quickly toward him, calling out in that ragged, pleading voice, her gaze and gait intense and focused. Almost all eyes were on her—except for those of the mayor, who shook a few more hands and then pivoted quickly and disappeared through a door, studiously ignoring Morley the entire time.

“Mayor Emanuel!” she cried again as he dashed out. “Please stay here, Mayor Emanuel!”

The abruptness of the exit, the cake sitting there untouched, the lack of closing niceties, and the crowd milling around awkwardly gave the impression that the event had been cut much shorter than planned.

With the mayor gone, Ginsberg-Jaeckle and fellow activist J. R. Fleming stepped up on the stage and lifted the banner behind the cake. Morley centered herself in front of them and turned to face the remaining crowd, earnestly entreating, “People are dying. They aren’t going to have nowhere to go!”

§ § §

Emanuel’s critics and admirers have both described him as a quintessential creature of Washington and Wall Street, a brilliant strategist and fundraiser who knows just the right way to leverage his famously abrasive personality to get wealthy donors to open their wallets and to help him win races. He became a prominent fundraiser for powerful politicians in his twenties, he made some $18 million in investment banking in just two years, he played central roles in two White Houses, and he orchestrated a dramatic Democratic takeover of the House of Representatives during his six years in Congress. He clearly knows how politicking works. But being mayor is different, or at least it should be. In Washington people are often tagged as political allies or adversaries, fair game for manipulation or intimidation. In Congress Emanuel represented his constituents, but the daily grind had a lot more to do with Beltway machinations and maneuvers. Running a city, where you are elected to directly serve people and listen to them, is supposed to be a different story. Emanuel was treating Chicago as if it were Washington. Perhaps that’s why, even in his brief tenure as mayor, he has seemed to find it so easy to ignore the parents, teachers, pastors, students, patients, and others who have carried out multiple sit-ins and protests outside his fifth-floor office in City Hall.

These citizens frequently note that Daley had not been particularly accessible, sympathetic, or democratic in his approach, but at least he would meet with people, acknowledge them, make perhaps token efforts to listen to their proposals and act on their concerns. Emanuel can’t seem to find the time for many members of the public, they complain, even as he says he wants their input on issues like school closings. Parents, grandparents, and students with the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (KOCO) camped out in City Hall for nearly four days trying to deliver a formal plan that community members had drafted in conjunction with university experts to protect their local school from closing and create a network of educational resources in the surrounding low-income neighborhoods.1

“His response was to ignore us,” said Jitu Brown, education organizer for KOCO, one of the city’s oldest and most respected civil rights organizations. “We had our problems with Mayor Daley, but Mayor Daley surrounded himself with neighborhood people and he himself was a neighborhood person. This man, Rahm Emanuel, has surrounded himself with corporate people. This administration is doing the bidding of corporations and robbing us of the things our parents fought for.”

§ § §

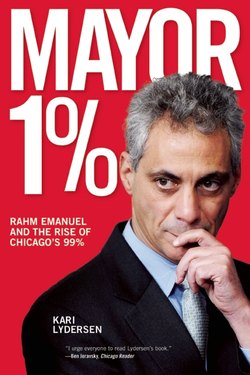

Photo by C. Sven.

Rahm Emanuel took the reins from his onetime mentor Mayor Richard M. Daley and brought a new style of corporate governance to Chicago.

If Emanuel thought primarily in terms of political and financial strategy, and the costs and benefits of how he interacted with certain people, it’s understandable that he would dart away from Helen Morley. But she was clearly a woman in deep distress, both at the birthday party and at previous protests at City Hall.

Did Emanuel ever direct a staffer to contact her and see how she was doing? To take her name and follow up? Even to put a reassuring arm on her shoulder? Morley was used to people edging away from her in public; they could tell she was a little off. But she didn’t appear dangerous or threatening. At the birthday party she didn’t even sound angry, just desperate and afraid, literally begging the mayor to speak with her, to hear her cries.

“They knew who she was, she was at every sit-in,” said Ginsberg-Jaeckle. “But she was never contacted by them, they never met with her, not once.”

Three months later, Helen Morley would be dead. Her friends blamed the closing of the mental health center. Of course, there was no direct link between the clinic closing and the heart attack that felled Morley at age fifty-six. But her friends are sure that the trauma of losing her anchor—the clinic and the tight-knit community there—is what pushed her ailing body to the limit. They said as much during a protest outside the city health department offices a week and a half after Morley’s death, with a coffin and large photos of her in tow.

“We don’t have an autopsy or a medical examiner’s report. You can’t show her death was related to the clinic closure,” said Ginsberg-Jaeckle. “But it would be hard for anyone to say that given her heart conditions and other conditions she suffered from, that the stress and cumulative impact of everything she was going through didn’t play a major role.”

If Emanuel did indeed think largely in terms of adversaries, Morley was not a worthy one for him. She was impoverished, unemployed; many saw her as “crazy,” as she herself sometimes said she was. Her unhappiness with the mayor and her death would cost him no political capital.

But Emanuel’s attitude toward Morley and the other members of the Mental Health Movement was perhaps emblematic of a deeper issue that would haunt him in the not-too-distant future. Although he seemed adroit at manipulating the levers of power, Emanuel did not seem to understand the power of regular Chicagoans, especially Chicagoans organized into the city’s rich mosaic of community groups, labor unions, progressive organizations, and interfaith coalitions.

This failing would become fodder for national pundits in the fall, as the Chicago Teachers Union made headlines around the world by going on strike and filling the city streets with waves of shouting, chanting Chicagoans clad in red T-shirts. Emanuel appeared shocked and disgusted with the union’s audacity, attacking them in a public relations campaign more reminiscent of a brutal electoral race than contract negotiations between two teams of public servants.

§ § §

Few would dispute that Emanuel is a highly intelligent, energetic, efficient, organized, and hard-working individual; these are clearly qualities anyone would hope for in their elected leaders. Emanuel let hardly a week go by without announcing a major new initiative or project, many of which were applauded and praised across the board. It would be hard to question his commitment to conservation and clean energy, safe bike lanes, beautiful parks, and other aspects of a livable city. He pledged to make Chicago one of the nation’s most immigrant-friendly cities, and he pushed state legislators to grant driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants and to legalize gay marriage. He courted employers, bringing thousands of new jobs to Chicago and positioning the city as a high-tech industry hub. He made common-sense improvements in efficiency, including reforming the city’s bizarre garbage collection system. After Mayor Daley left a yawning budget gap and leased the city’s parking meters in a notorious deal that would leave taxpayers paying the price for decades to come, many understandably welcomed Emanuel’s business acumen, fundraising ability, and determination to whip the city into fiscal shape.

But Chicagoans should have been able to expect that a leader with such skills, experience, and connections would listen to their ideas, address their concerns, and solve some of their problems—rather than ignoring them or treating them as the enemy when they questioned his actions, priorities, or motivations.

Many pundits describe Emanuel as the epitome of the modern centrist neoliberal Democrat. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is often viewed as a symbol of neoliberalism, a global socioeconomic doctrine with intellectual roots in Chicago. Emanuel was a key architect of the trade agreement, which ultimately cost tens of thousands of US jobs and brought social and economic devastation to Mexico.

To the extent that Emanuel genuinely wants to make the world a better place for working people, he thinks market forces and business models are the way to do it, and he clearly (and perhaps rightly) thinks that he understands these institutions far better than any teacher or crossing guard or nurse. From that viewpoint, the messy attributes of democracy—sit-ins, protests, rallies, people demanding meetings and information and input—simply slow down and encumber the streamlined, bottom-line-driven process Emanuel knows is best. But many regular Chicagoans see injustice, callousness, and even cruelty in this trickle-down, authoritarian approach to city governance. They see the mayor bringing thousands of new corporate jobs subsidized with taxpayer dollars while laying off middle-class public sector workers like librarians, call center staffers, crossing guards, and mental health clinic therapists. They see him closing neighborhood schools, throwing parents’ and students’ lives into turmoil. They see him (like Daley) passing ordinances at will through a rubber-stamp City Council, leaving citizens with few meaningful avenues to express their opposition to policies changing the face of their city.

This book explores Chicago’s embrace of privatization and public-private partnerships: an increasingly popular urban development strategy that community and labor leaders say can be beneficial and productive if carried out right. But like residents in other parts of the country, many Chicagoans fear that the encroachment of the private sector on the public realm is increasing economic and racial inequality and sidelining unions and democratic processes. Continuing a trend championed by Mayor Daley, Emanuel has pushed for privatization of various city properties and services—including education and health care—and garnered national attention with his public-private Infrastructure Trust.

This book also details how privatization and cost-cutting, along with larger ideological debates, were central to Emanuel’s battles with organized labor—long a storied and powerful constituency in Chicago. And it depicts the popular movement that arose around the NATO and G8 summits, describing how that movement became a defining struggle over civil liberties, economic priorities, and transparency at the city level.

The description of Emanuel’s early life and his time in Congress, the private sector, and the Obama and Clinton White Houses was compiled through interviews and largely through reliance on books and media documenting these eras. Starting with Emanuel’s campaign for mayor of Chicago and extending through his first two years in office, the content is based primarily on firsthand reporting supplemented with other media and analysis; it is also informed by my fifteen years of reporting on organized labor, immigration, community struggles, and grassroots movements in Chicago.

Although this is a book about Rahm Emanuel, it is also a story about organizations—like the Mental Health Movement and the Chicago Teachers Union—made up of regular people who are finding it harder and harder to secure basic rights including housing, health care, and a voice in their governing institutions.

I aim to explore what these actors stand for and how they pursue their goals at a time when many Americans have embraced a view of the country that pits the “99 percent” against the “1 percent,” “Main Street versus Wall Street,” and feel neither political party is really representing their interests.

By his second year in office, Emanuel—a famous Democrat running a city famous for Democratic hegemony—was frequently being compared to prominent right-wing Republicans including Wisconsin governor Scott Walker and even presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Such allusions were great oversimplifications, but they showed that many Chicagoans did not feel that their Democratic mayor was actually interested in democracy, transparency, or a system that genuinely seeks equity for the have-nots.

Emanuel cut his teeth in opposition research, a then-emerging field in which political operatives secure victories in part by acting as private eyes, digging up dirt or spinnable information on opponents and leveraging it for political gain. Given this expertise, and his mother’s activist background, it is perhaps surprising that Emanuel did not seem to understand the history or culture of popular resistance in Chicago—or anticipate that activists and organizers would become a thorn in his side.

If there’s one thing Chicagoans have demonstrated ever since the city rose out of a swamp of stinking onions, it is that they will not quietly acquiesce when they sense injustice. This rich tradition stretches from the Haymarket Affair of 1886 to the garment workers strikes of the early 1900s; from the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests to the first massive immigration march of 2006. Like the proud Chicagoans who came before them, the Chicago Teachers Union, the Mental Health Movement, and other contemporary groups are committed to questioning and shaping the meanings of democracy, leadership, power, and justice.

Rahm Emanuel’s tenure as mayor of Chicago has provided a stage for these populist and progressive institutions to grapple with other powerful forces in a drama about the continual evolution of a great American city.