Читать книгу Food of London - Kathryn Hawkins - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart One: Food in London

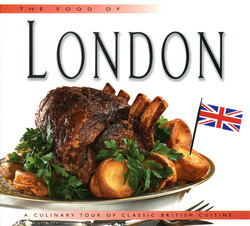

London offers a wide range of culture and cuisine

by Kathryn Hawkins

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, London was transformed from a city of bland and uninspired culinary offerings to one of the greatest food capitals in the world. London has always been one of the best-loved cities in the world for its history, arts, and architecture but its food had never been a selling point. Recently, however, a culinary revolution has occurred. From pubs to smart restaurants, young, innovative British chefs are reinventing national favourites, foreign chefs are flocking to the city from all over the world, and immigrants from the West Indies, Africa, the Subcontinent, and the Far East have brought with them new ingredients and cooking styles, all of which has resulted in London's restaurant scene becoming the envy of the world.

Such a cosmopolitan flavor is due not only to recent developments, as, from the Roman conquest of the British Isles in AD 43 onwards, London has already been a magnet for travelers and settlers from around the globe. Migrants have brought their own unique culture and food, giving London the distinctive global melting pot of flavors and influences it has today; cuisines from all over the world can be found here, from the more common Indian and Chinese, to Middle Eastern, Africa, and South American.

Of course, the traditional cooking of Britain must not be forgotten, and there are endless places in which the food lover can sample local food—from fish and chips—a wicked combination of succulent white fish deep-fried in crisp batter and served with juicy, thick potato chips (fries) with malt vinegar—to the pie and mash, jellied eels, cockles, winkles, and curry houses of London's East End.

Many restaurants and pubs serve traditional Sunday lunches of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, roast pork with apple sauce, or roast lamb and mint sauce, usually followed by apple pie and custard. A person with a hearty appetite could well start the day with an English breakfast, which typically consists of bacon, sausages, black pudding, fried or poached eggs, mushrooms, tomatoes, baked beans, and fried bread or toast. Some of the smallest cafes offer the best value for money.

Most people's initial thoughts of London are of the royal family, Buckingham Palace, the Tower of London, and the Houses of Parliament. Yet, behind all the tradition and the pomp and ceremony of formal London, there is a truly contemporary and cosmopolitan flavor to Britain's capital city. So, the next time you're in London town and you feel the pangs of hunger coming on, remember that you really are spoilt for choice!

A Culinary History of London

From the Romans to the present day

by Kathryn Hawkins

When the invading Roman legions reached Britain in AD 43, they introduced a variety of foods, such as peacocks, fallow deer, pheasants, figs, grapes, mulberries, walnuts, and chestnuts, as well as many of the herbs we cultivate today, including parsley, dill, mint, rosemary, and sage. They also brought vegetables, such as cabbages, onions, garlic, lettuce, turnips, and radishes. Add to this a list of culinary commodities like dates, almonds, olives, olive oil, ginger, pepper, and cinnamon, and it is clear to see their profound influence.

In London (Londinium as it was called), some essential foods were locally produced. Salt, used for preserving and flavoring, came from the Thames estuary, and oysters were collected off the Kent coast. As well as trading with every part of the Roman Empire, London became the center for grain supplies, and for many centuries thereafter, locally grown grain and other farm produce could easily be brought to the capital from Kent, Essex, Surrey, and the Thames valley by river or road for trade and distribution.

The Romans loved feasting; these diners are celebrating the feast of Hortensius.

The next important period in London's culinary history is between 1066 and 1520: medieval London. Sugar arrived in Britain courtesy of the Crusaders who brought it back from the East. Packed in white or brown cone shapes, it was very expensive and was regarded as a spice. Around 1290, citrus fruits began to arrive, and lemons were used fresh or pickled, as well as Seville oranges.

The range of imports and exports handled in London's harbors, wharves, and markets was impressive. They included strawberries, cherries, peas, beef, cod, mackerel, pepper, saffron, and cloves.

The earliest surviving recipe books date from this time. Fed up with salt, pepper, and the homegrown mustard and saffron used as flavorings, people were looking further afield to more exotic tastes, such as nutmeg, mace, cardamom, and cloves. These spices became highly sought after for their pungent, aromatic flavors. However, these spices were expensive as they were not imported direct and had to be purchased from markets in mainland Europe.

During the sixteenth century, the basic English food and diet remained the same as that of the previous era. Roast and boiled meat, fish and poultry, bread, ale, and wine formed a large part of the diet of the upper classes, and fruit and vegetables were less popular. In fact, during the great plague of 1569, the sale of fruit was banned in the streets because it was believed to cause sickness. After about 1580, however, there was a growth, in market gardening, and by the turn of the next century, Londoners, who had always bought their fruit and vegetables from France and other parts of Europe, were able to buy from the orchards and gardens of Kent, Surrey, Middlesex, Essex, and Hertfordshire. Even city gardeners were successful with only a few acres of land because demand was so high. For the more discerning and wealthy palate, new produce was still arriving from foreign shores—quinces, apricots, raspberries, red and black currants, melons, and pomegranates, as well as dried fruits and nuts.

This was the time of exploration and a number of rare and exotic foods began to arrive back in Elizabethan England: tomatoes from Mexico, kidney beans from Peru, turkeys and potatoes from Central America. Sugar grew in popularity, and from the 1540s a London refinery was busy making coarse crystals into tightly-packed white crystalline cones. Sugar was used increasingly in preserving and for making all sorts of sweetmeats.

Coffee, chocolate, and tea arrived at the end of the century, and by the turn of the next, cookery books included recipes for dishes from Persia, Turkey, and Portugal, showing an ever-increasing fascination and demand for foreign flavors and delicacies; even ice had been introduced from the Continent at this time, as an idea for preserving.

By 1800, England was on the brink of the modern era, as the balance of power shifted from the land to the towns with the rise of the prosperous new middle classes, the development of newspapers and advertising, and the birth of a consumer society.

Cardinal Wolsey presides over a banquet in the Presence Chamber at King Henri VII's Hampton Court palace.

The beginnings of what has now become one of London's leading supermarket chains: J. Sainsbury's grocery store circa 1920.

The making and taking of tea became an elegant ceremony amongst the middle and upper classes in London. In 1717, Thomas Twining had opened the first tea shop for ladies—there were already coffee shops for gentlemen—and in 1720, the first tea garden was opened in the old Vauxhall Gardens. This "fashion" soon spread, and tea eventually became an important social drink and industry.

Cooking methods changed from open fire and spit roasting to flat iron griddles and plates on hobs. Roasting was the most important method of cooking, followed by boiling in a large cauldron, and then stewing and sauce-making over a gentle heat. Ice houses were built by the fashionable, and ice creams became a speciality. New recipe books of the period were written for the gentry and aimed to encourage them to aspire to a higher standard of living. Dinner table layouts, table manners and etiquette were featured, together with suggestions for different courses.

The style of eating also changed: simply flavored sauces and melted butter were served with meat dishes and vegetables alike; the pudding was invented—both savory and sweet; and sweetbreads and cakes were popular as sugar came down in price.

Hothouses grew tomatoes, grapes, peaches, and salad vegetables. The advances and discoveries in agriculture led to cattle and livestock being bred for meat production all year round, and farm animals began to replace wild ones in the nation's diet. The big landowners gained control over the wild game on their land owing to the new land enclosure acts and the enforcement of severe gaming laws.

The poor, on the other hand, suffered in London as they did elsewhere. Thousands of rural laborers had lost their small homes and vegetable plots as a result of land enclosures, and were reduced to poverty and a diet of bread and potatoes. In London, working class families ate bread, potatoes, poor- quality meat and offal, fish, milk, tea, sugar, beer, butter, lard or dripping, and cheese. Supplies were inadequate and many were almost starving.

A busy scene at Billingsgate fish market in London in 1935.

Advertisement posters from the 1930s for two popular meat extract drinks, Bovril and OXO

However, as the eighteenth century drew to a close, food production increased in the United States, South America, Europe, India, and Australia. Transport became cheaper, and food processing techniques, such as freezing, canning, and bottling, were developed. Food prices fell, "whilst wages remained the same, and consequently the poor were able to afford a better diet.

South London became an important center for manufacturing branded foods: Crosse and Blackwell, who made pickles, sauces, and condiments, had a factory in Southwark; Peak Frean and Company made biscuits in their Bermondsey factory; and Thomas Lipton started jam production.

In 1869, John Sainsbury opened his first grocery store in Drury Lane, offering a wider range of culinary goods than ever before, and aimed at the new middle classes. This store became the predecessor of the modern-day supermarket. By the early 1900s, several were operating in Britain and the "multiple ownership" culture was born. It wasn't until 1949 that the first self-service shops were opened, and supermarkets only became commonplace in the 1960s.

By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Britain was dependent on imports for half of all its food. Shipping losses during wartime began to cause food shortages. Strict pricing controls were enforced, and in 1918 rationing was introduced with the result that both the rich and poor were eating the same food. Ironically, it enabled many working class people to have a better diet than prior to the restrictions.

In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II, the Government began another system of food rationing which remained in operation until 1954. Rations were strictly calculated to ensure that the population remained healthy. Many everyday foods became unobtainable, and ingenious substitutes were developed for eggs, cheese, bananas, and chocolate.

An important factor in London's recent culinary history is its migrant population. It has seen its fair share of migrant workers throughout its history, but the twentieth century witnessed the largest ever rise in its immigrant population. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Irish established their own community in West London. Many Poles arrived in postwar London, mainly servicemen fleeing occupied France, as well as those who had been in Germany as prisoners or conscripts. Many Italians also came to London and successfully merged into the local communities, opening up bistros and pasta restaurants. Greek Cypriots started arriving in the 1920s, bringing with them their flair for catering.

After 1945 West Indians were recruited to work for public service companies. Brixton and Notting Hill are well known for their colorful markets selling exotic produce from the Caribbean homelands. The relaxation of emigration restrictions in India and Pakistan in the 1960s created a rush of migrants, and many settled in London. Today, Brick Lane is synonymous with curry houses and Asian cuisine, and Southall and Tooting are popular Asian centers. Other areas of London famous for their ethnic populations are Golders Green and Muswell Hill for the Jewish community, Soho for London's Chinatown, and the Edgware Road for the Arab quarter. London is now a truly cosmopolitan city, and it is possible to eat out in restaurants from all corners of the globe.

Most families sit down to a large Christmas lunch of roast turkey; roast potatoes; roasted seasonal vegetables, such as parsnips; and dessert of rich Christmas pudding and brandy butter.

Feasts, Festivals, and Celebrations

Contemporary London food is still influenced by the traditional feasts of the past

by Kathryn Hawkins

Throughout the year, all over Britain, festivals and celebrations take place to commemorate specific events or to maintain religious, pagan, historical or sporting traditions. There are also quite a few unusual and often superstitious traditions which take place in London. Many traditions involve feasting and the preparation and baking of special food for the occasion. Londoners also have their own festivals which relate specifically to the city's multi-ethnic society and the individual cultures that make London so cosmopolitan.

One of the traditions carried out in the theater world occurs on January 6 at the Drury Lane Theater, where the cast eat cake and drink wine as directed in the will of a comedian called Baddeley, who died in 1795. Another less well known event takes place two days later on January 8, or the first Sunday after, when the Chaplain of Clowns preaches a sermon and recites a prayer over the grave of the great clown Joseph Grimaldi. A wreath is also laid. This ceremony takes place by the former St. James's church in Pentonville. In January or February, depending on the lunar calendar, London's Chinatown becomes alive with the sights and sounds of Chinese New Year celebrations. Gerrard Street in Soho (in London's West End) is decked out in symbolic red and gold; lanterns and lights are hung from windows and street lamps, and the streets are packed with people all eager to see the Dragon dancers performing to the Chinese drummers and musicians. All the shops, bars and restaurants prepare themselves for a busy few days at this time of year.

Depending on when Easter falls in the calendar, the day before the beginning of Lent, Shrove Tuesday, heralds the start of a forty-day period of fasting for Christians, which ends on Easter Sunday. Although nowadays, few people observe Lent, nearly everyone eats pancakes, and it is now usually referred to as Pancake Day. Pancake races are held, in which competitors have to run with a pancake in a skillet, flipping it up in the air and catching it again. If a pancake is dropped, the participant is disqualified.

Pancake racers on Shrove Tuesday. This tradition is still practised all over England to mark the beginning of Lent.

On the fourth Sunday in Lent, Mothering Sunday is celebrated. In medieval times it was the day when people traveled to their Mother Church or Cathedral to worship. It wasn't until the mid-seventeenth century that it became linked to the family. A favorite bake was the Simnel cake—a fruit cake with a marzipan topping. The cake is decorated with twelve marzipan balls to represent Christ's apostles and is a popular addition to the Easter tea table.

One of the oldest Druid ceremonies takes place on March 21st on Tower Hill to celebrate the spring equinox. Later in the year (around September 23), they meet again to celebrate the autumn equinox.

Good Friday is the most solemn day in the Christian calendar, and church services are held all over London. After morning service at St. Bartholomew the Great in Smithfield, 21 widows of the parish collect a bun and sixpence from the top of a tomb in the churchyard. Two days later, Easter is celebrated, marking the end of Lent, and it is an opportunity for families to gather for a feast of roast lamb. The shops are stocked with Easter eggs and chocolate bunnies. In London's Battersea Park, the annual Easter Parade is held.

The feast of St. George, patron saint of England, falls on April 23. George is believed to have been a Christian centurion who was martyred by the Roman Emperor Diocletian at Lydda in Palestine around AD 303. He took on a symbolic importance to the English when Richard the Lionheart recaptured the church at Lydda during the Crusades. In 1415, his feast day was declared a national religious festival in England after the Battle of Agincourt.

Pearly Kings and Queens, descendants of London's earliest fruit & vegetable sellers, are the East End's most famous inhabitants.

To commemorate the Queen's official birthday in June, crowds gather to watch the Trooping the Color at Horse Guards Parade. The Queen inspects her Guards as they march past and then proceeds to Buckingham Palace at the head of them. This heralds the beginning of the "summer season". The race meeting at Royal Ascot in the third week of June has a strict dress code: men wear lounge or morning suits with top hats, and the women dress up, too, especially on "Ladies Day" when they wear their most extravagant headwear. The Wimbledon lawn tennis championship takes place in the last week of June and first week of July. Tonnes of strawberries are served with cream, and gallons of Pimms and champagne are drunk.

Meanwhile, at the Henley Royal Regatta, blazer-clad men and women in floating dresses picnic on the tables and chairs set out in front of their Rolls-Royces or Bentleys!

At the Bank Holiday weekend at the end of August, a carnival takes place in London's Notting Hill. Staged by the West Indian community, the participants parade in colorful costumes and dance to pulsating reggae rhythms. The streets fill up with thousands of people and the partying continues well into the night. Street vendors sell West Indian foods.

As summer fades away, Harvest festival is celebrated in churches with altars laden with sheaths of corn and baskets of fruits and vegetables.

On November 5, 1605, Guy Fawkes, a Catholic, was found in the cellars of the Houses of Parliament, planning to ignite barrels of gunpowder later that day when the Protestant King James I was to open Parliament. Every year, to commemorate the foiling of the plot, children make replica 'guys' which are burnt on bonfires. Firework displays and bonfire parties are held all over Britain.

As the year draws to a close, the shops are piled high with Christmas goodies gifts. Houses and streets all over the country are decorated with lights and Christmas trees. London's Regent Street and Oxford Street are illuminated, and Trafalgar Square is adorned by a huge lit Christmas tree, a present from the people of Norway. On Christmas Day, brave members of the Serpentine Swimming Club plunge into the icy river to race for the Peter Pan Cup. On December 31, people gather in Trafalgar Square and at the London Eye to welcome in the New Year. As the chimes of Big Ben strike midnight, they join hands and sing "Auld Lang Syne" and the celebrations for the New Year begin.

Revellers in the streets at London's Notting Hill Carnival, the largest carnival in Europe.

Eels, Pie, and Mash

For a taste of real East End Cockney food, you can still savor pie and mash

by Charlotte Hunt

Pie, mash, and liquor, together with jellied or stewed eels, are often perceived as Cockney food—a speciality of London's East End. It's true that today the majority of the distinctive eel, pie and mash houses are situated in this part of the capital, and many of the original establishments, from the 1840s onwards, sprung up here. However, just after World War II, you could eat this traditional dish in at least 130 shops all over the city from Soho to Bermondsey.

Sadly only a fraction remain, as the arrival of fast food and worldwide gastronomic influences have brought about the partial demise of this traditional fare. However, the trade is still dominated by three families—the Cookes, Manzes, and Kellys, whose history is an important part of the pie and mash story.

No one knows who invented the dish or opened the first shop. We do know that in Victorian London, street vendors sold eel pies, providing cheap yet nutritious food for the poor. These were eaten with parsley sauce, spiced with chilies and vinegar, which survives today as the famous green liquor.

Ealing eel and pie shop that serves traditional pie, mash, and eels to Londoners.

The eels originally came from Holland and legend suggests that John Antink, a Dutch trader, sold the fish from a makeshift shop, although Kelly's Trades Directory doesn't mention this business until 1880. However, we can verify the existence of an eel and pie shop in 1844 at 101 Union Street, London SE1. Here a man called Henry Blanchard sold meat, eel, and fruit pies for a penny as well as live eels and mashed potato. By 1874, Kelly's listed 33 eel and pie shops, and their success no doubt encouraged Robert Cooke to open his own establishment in Clerkenwell in 1889, officially launching the Cooke eel and pie empire. Staff wore white aprons, and a typical shop had white-tiled walls, marble tables, wooden benches, and huge mirrors. There were two large windows on either side of the front door, which opened up to provide a takeout service. The customers spat eel bones onto the sawdust-covered floor, although everything was scrupulously clean and the interiors had a simple elegance and charm. Inspired by his success, Cooke swiftly opened up a second shop in Watney Street El while his wife opened a third shop in Hoxton Street Nl. Another pie and mash pioneer, Michaele Manze, arrived from Ravello, Italy, in 1878. He soon became friends with Robert Cooke, married his daughter Ada and opened up the first Manze shop in Bermondsey.

Finally, Samuel Kelly, an Irish immigrant, opened his Bethnal Green Road shop in 1915 and by the 1940s the business had expanded to include four other shops, all within a mile and a half radius.

Pie and mash survived the World Wars despite conscription of the white working class males who made up the majority of regular customers. The shops upheld their reputation for supplying good reasonably priced food although eels were scarce and eel pies largely disappeared from the menu.

Rewards were justly reaped when the wars were over and boys in their demob suits flooded the shops desperate for a taste of their favorite cuisine.

Pie and mash enjoyed huge popularity and for the next few years London's thriving docks, factories and markets guaranteed an enormous demand.

In the 1950s, rising rents forced many factories to move out to newly built towns in Essex. The pie and mash clientele moved with them and the number of London shops decreased to the present-day figure of around thirty.

Shrewd local businessmen opened up similar eating houses in the new towns as well as nearby seaside resorts, ensuring that pie and mash was no longer exclusive to London. However, the original proprietors still claim that customers travel for miles to enjoy the dish in its "proper" form.

The Cookes still have four shops, and the Manzes, who proved themselves the true entrepreneurs of the business with 14 shops, still have five branches. Five Kelly's shops also continue to thrive, serving East End regulars and visitors as they have done for 86 years.

Many London families remain loyal pie and mash enthusiasts and the meal has recently been discovered by the middle classes intrigued by this slice of culinary history. Hopefully, the appeal of cheap, tasty sustaining food eaten in historic surroundings will survive.

A live eel prior to preparation in the kitchens of F. Cookes pie and mash shop in Broadway Market.

Dining Out in London

In Londons ethnically diverse eateries, you can eat truly cosmopolitan food

by Guy Dimond

London just isn't like the rest of Britain. It's still true that finding a good meal in rural Britain—or even some of the larger cities takes sleuth-like skills and a well-thumbed copy of The Good Food Guide, but London has become a center of excellence which is now on a par with the best food cities in the world, such as New York, San Francisco, and Sydney. And this has happened within the last 15 years or so. If you haven't visited London for a few years, then you're in for a big shock.

London always had the makings of a great restaurant city, but for some reason it just didn't take off until the 1980s. London's a wealthy city; it has a huge population (over seven million people, depending on where you consider the boundaries of "London" to lie); and it's a multicultural city, so there's a score of diverse communities who have brought their food cultures to the city. Londoners are less conservative in their dining habits than other British people or, indeed, other Europeans. And, of course, London doesn't just comprise British-born people. Britain has long been a member of the European Union; as more European countries join, chefs from Stockholm to Lisbon are able to work legally in London. Equally, young chefs from Commonwealth countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, find it easy to get work

(for a couple of years at least). And when Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997, many of the best Cantonese chefs decided it was time to move to London, making London's dim sum some of the best you'll find anywhere. Chefs apart, London itself is an ethnically diverse city: by the year 2050, more than half of London's population will have one or both parents of Asian or African heritage.

London's multiculturalism is only a precondition of it being a great city for eating out—what has really driven the restaurant boom is the growth in disposable income. Between 1986 and 2001, there was an increase in the average household income of around 40 percent. This occurred at the same time as a drop in the cost of living (in real terms). This might be hard to believe as London is still the most expensive city in Europe, but Londoners simply have more money than they've ever had. And think back to the 1980s; for a short while, Greed Was Good, and the previous British reserve about throwing money around in bars and restaurants evaporated.

The colorful dining room at The Square Restaurant in the heart of Mayfair.

The glitzy Criterion brasserie, located on Piccadilly Circus, London's only neo-Byzantine restaurant.

The Warrington hotel, formerly owned, in the late 1800s, by the Church of England, now a bar and restaurant.

Restaurateurs such as Sir Terence Conran sniffed the change in mood and realized that the time was right to build lavish, opulent restaurants. One of the first of the grand designs was Quaglino's, which Conran modeled on the Parisian brasserie La Coupole. It was spectacular; it was pricey; it also served good food. Conran judged that Londoners were ready to appreciate the theater and fun of eating out, and were no longer just concerned about portion sizes and price. Conran continues to build an empire of expensive but well-managed restaurants to this day.

A revolution was also happening at the other end of the price scale. Cheap fast food in London had previously been dominated by second-rate pizza and pasta places, or kebabs and burgers; there weren't even many good sandwich bars. Then, in 1986, Pret a Manger opened its first sandwich bar, selling ready-made but high-quality sandwiches, and now there's one on every major street in central London. In the 1990s, espresso chains took over the high streets, though these are more clearly modeled on (or even owned by) State-side chains, such as Star-bucks. Asian food in London had previously been dominated by Chinese takeaways and Indian curry houses, but in 1992 Wagamama created a huge stir when it opened its first branch. Food from the Far East had previously been "ghettoized", but Wagamama's intriguing mix of Japanese-style noodles mixed with Southeast Asian flavors was a huge hit. The restaurant is cheap and theatrical. The huge, minimally designed space features shared bench seating, fast turnaround, and quick-moving lines (no bookings are taken). Alan Yau, its creator, sold the growing chain, then went on to set up Busaba Eathai (which does a similar thing with Thai food) and, in 2001, opened Hakkasan (a very glamorous Chinese restaurant serving dim sum at lunchtime).

Besides the mass-market budget restaurants and the big names like Conran, there is also a quieter revolution going on in London's kitchens. It started a long time ago, arguably with the cookery writing of Elizabeth David in the 1960s. However, it took until the 1980s for her Mediterranean approach of using the finest ingredients and preparing them simply to start appearing on smart restaurant menus. Previously, London's top chefs had been pursuing the Michelin route—using the decades-old French approach of lots of butter, cream, meat, and reduced sauces. French haute cuisine was becoming less appealing to a more health-conscious public.

Early pioneers of the so-called "Modern British" cooking included Alastair Little opening in Soho in 1984, and, also in 1984, Sally Clarke who introduced "Cal-Ital" cooking to London (having learned her approach from Alice Waters in Berkeley, California). Soon their style of cooking became the norm. However, the term "Modern British" is a misnomer; there's not much that's typically British about ingredients like lemongrass or harissa, or cooking techniques like char-grilling or searing. The term "Modern European" is now usually preferred (and it's much the same as "Contemporary American" or "Modern Australian" cooking). If you singled out London's top 100 restaurants, around 70 could be categorized as "Modern European".

The British still like their pubs, even though by the 1980s many London pubs were owned by a handful of brewery chains selling mass-produced, insipid, or badly-kept ales and lagers. The reaction to this was not a groundswell of people clamoring for real ales; instead they switched to other drinks—bottled beers and pre-mixed alcopops—where at least the quality was consistent. A few pubs continue to champion real ales and even microbrewed ales, but one of the biggest changes is that London's pub owners have realized that there's money to be made by serving customers good food as well as drink. One of the first and most influential gastropubs was The Eagle in Farringdon. It strived to be a happy mix of both pub and dining area, so there was no pressure to just eat or drink; the beers were good, there was even a decent wine list, and the cooking was an unusual style of Iberian-inspired dishes. It was a huge hit, sparking a wave of spin-off gastropubs and restaurants, such as the much lauded Moro. London's gastropubs go from strength to strength. Some of the best meals I've eaten this year have been in gastropubs, not chi-chi restaurants.

The Chef at Satsuma, in Soho, shows of a bento box.

The Blue Posts consist of four pubs in Soho, London, which serve a number of well-cellared and popular beers.

London is a genuinely exciting place to eat out, because there's something for everyone. If you like budget "ethnic" restaurants, there are delightful cafes like the Sudanese Mandola in Notting Hill, the Vietnamese Viet Hoa in Hoxton, the Burmese Mandalay on the Edgware Road, or the Turkish Mangal in Dalston.