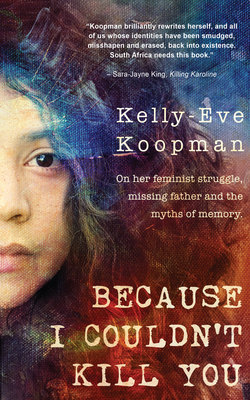

Читать книгу Because I Couldn't Kill You - Kelly-Eve Koopman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Scavenger hunt

ОглавлениеThis is the part where I must go searching for clues. Start a private investigation, to figure out the evidence, to make the map, intrepid, idealistic. I think of the books of my early childhood. The Famous Five, Harriet the Spy, stories about kids going on uncanny escapades, armed with pens, notebooks, an attitude for high jinks and Blyton’s iconic lunches of hard-boiled eggs and lemonade. Beautiful stories that are easy to grow out of and not because the stories are dated, but because the characters don’t fit anymore. Now there are bogs and quagmires and swamps that cannot be navigated with the help of a good pair of sneakers and a healthy picnic lunch.

I will start searching for you, placing together the symbols and signs, the markings and droppings, the jumbled evidence of you. Step one of the hero’s journey, according to the canon, is to search. I do not have to look far. Although I have tried my best to erase you, to forget, this has been a pathetic assassination attempt on memory, a botched exile of the heart.

There is no need for trawling through the bars, or homeless shelters, mental institutions or morgues. There is no need for a dead body. Or for a body of any kind. I can’t forget you. I understand the concept of being triggered but you are more like a landmine. I am a young adult, I am cultivating my own life; you are not a part of it. But the memories of you detonate all the time these days, abrupt and explosive. You make yourself known all around me, everywhere, inappropriately, inconveniently – in the dead giants behind the glass cages of a museum, in the worn-out titles of many much-loved books. You are there ‘brillig’ in the ‘slithy toves’, an ephemeral monster constructed by adjectives and the imagination.

I have found myself playing opposite you, summoned by the couplets of Shakespeare sonnets. All of us – me, my brother, my sister – were taught by you to recite ‘Let me not to the marriage of true minds’ pretty much as soon as we could read. I still don’t really know why. And while there’s no trace of you on social media, I find you popping up on my Facebook timeline often, most recently in memes. I think you’d really like the Ayn Rand ones, particularly the ones that encourage the use of The Fountainhead as toilet paper. While you taught me to read, to appreciate beauty, you also taught me to read with a question for every word. And once, when I was quite young and easily malleable to the artful framing of individualism and exceptionalism by Ayn Rand and the DA, I showed you a chapter in We the Living, enamoured by her fiery anti-proletariat prose. We had a long talk about what conservative propaganda was and how it could sometimes look like art.

You are the reason why I have most of my most beloved paperbacks and so now you lean, slouched in the best shelves of my bookshelves. You would look over what I was reading with utmost attention, and ask me questions, challenge me to go exploring for the meaning of every word I didn’t know and best of all give me recommendations. The best times we had were when we went to the Bellville library together. We would spend hours selecting just the right collection of books that you’d let me pick from the adult section once I’d read everything decent from the kids’ one. I suppose you also wanted to divert me from the teenage pulp, the endless literary quicksand of Sweet Valley High and Drina Ballerina. Nevertheless, your quiet nudge toward Toni Morrison, that would become the best blind date I’ve ever had with literature. Also, a gentle push toward a second-hand copy of The World According to Garp, the tattered pages carrying multiple copies of both our fingerprints and our mutual coffee stains. We can now both never forget the sinister, incessant pull of the Undertoad. You had gentle hands when handling books. Not so much your family.

There was a time, believe it or not, when you travelled further than the no man’s land of the kitchen and came back with rolls of reproduction paintings in enticing triangular cardboard boxes with names like the Louvre. And with stern instructions that they should never be opened. Once you were gone, they remained there, sealed like scrolls. Until I hungrily pulled them out, fucked them up by trying to stick them up, unframed, with Prestik. And now they’re rolled up in a broken laundry basket. Van Gogh’s reproduction Sunflowers, grubby, gathering dust.

Once you presented me with a pretty remake of Klimt’s The Kiss on a piece of cardboard with a crayon inscription on the back in your loose, loopy handwriting. The message was about chasing dreams and being unafraid to bring brightness and beauty into the world. There is a small, almost discernible crack down the middle of it and the green waxy writing is no longer legible. Once, being transported around in the back of a car, it got trampled on and cracked almost in half. I couldn’t throw it away. So Sarah found a place where we could get it glued back together. It is the only inheritance I will ever have from you. It also sits up on a shelf in the new home I share with my partner by the beach. A home you will never have the privilege of visiting, at least not in physical form.

You have not only left evidence of yourself on my bookshelves or in my quiet intimate spaces. I find myself confronted with you most often when I am far from home. Once in the middle of an art gallery in London, a famous painting that I’d never been particularly impressed by before brought me to tears. The painting I’d made all sorts of unfair assumptions about was The Starry Night, hung up in the middle of the Tate, and I started crying recklessly and without inhibition. I remembered when you’d told me about Van Gogh and showed me a picture in a book and tried to explain why it was so incredible. I wasn’t impressed, much more moved by the wild, evocative strokes of the weird pieces of modern art that through your eyes I learned to understand made absolute sense.

I’m making you sound like Dorian Gray, preserved all at once in a picture frame and the words of a modern classic. But here I have the power of the telling; on the page you are not in charge. People are immortalised by the books they wrote, not the books they loved. You are not art. This is not where I must find you. It is an easy mistake to make – to remember fucked-up men as brilliant, eccentric, to be determined not to separate the art from the artist, Woody Allen, Pablo Picasso, to turn a blind eye to the abuses and the sexual assaults in favour of appreciating all the pretty colours.

So after the trips to the library and some world-class art galleries, the Fantastic Five must go sleuthing for the next set of clues. Sometimes I think the only logical answer to where you went is that you merged with your old car. So I should go looking for the corpse of an old, metallic blue BMW with no plates. I don’t know the model. When you bought it, a once stately sedan, you made us children understand that this, along with your pager, could be talismans that provoked great envy, should we choose to use them. The speakers always klopped Carlos Santana or Queen. You told me you’d teach me to drive it. You apparently told my younger brother you’d leave it for him. But it was left for dead, an unsalvageable monolith that lived forever on my uncle’s lawn. This was the last place we had known as your headquarters. Until you were no longer welcome in the spare room. The fodder of nightmares for my two cousins. And for some of their friends, apparently. The last time I saw the BM it had moss growing from its radio, which was stripped of a face. It had grass clinging desperately to the hubcaps as if rooting it in the ground. There was a frog sleeping under the hood in its hollowed-out innards, which entered and exited via the exhaust pipe. And everyone was afraid to open the doors because apparently there was a wasp nest growing inside. I’m sure my uncle didn’t appreciate the corpse of a car rotting on his lawn. But I thought, for you it wasn’t a bad way to go. The car disappeared from the lawn shortly after you did. Went on mysterious vacation. And maybe this is where you live now. In the shell of the ancient BMW. Maybe you have taken up residence in a field somewhere, on the top of the mountain, in the bottom of a heap of earth. The car no longer drives – not the least bit roadworthy but fine for reptiles, and wasp nests, and all kinds of weeds. You could be in there somewhere, sleeping in the back seat or otherwise melded to its rusted guts.

But you are there in my bathroom cabinet, too, just beneath the mirror. All squeezed in the bottle of No More Tangles I use to get the knots out of my thick, dark hair. I have been trying to commit to combing my hair out at least once a week, as part of the practice of self-care. And here you are tangled up in my fucking hair. If you’re a black or brown woman one of your earliest memories probably has something to do with your hair and it’s probably not positive. I’m lucky that back then you were gentle. Maybe I was three or four, your big hairy hands more cautious than my mother’s, careful to brush softly across the knots and rescue all the curls with Johnson and Johnson’s No More Tangles. You’d always use so much of it that sometimes I thought that soap and baby hair was just the smell of your hands. It would only be a little sore, and every time I’d wince or yelp, you’d say in a soft voice, ‘Almost done, only one more minute’. You’d arrange the curls on top of my head like a little halo. You told me never to let anyone make me believe it would look better straight. This was good advice. When your hands moved toward my head in the years after that it was never a good thing.

There are three of us who carry your name and other arbitrary parts of you around in ourselves. We are still left, in all our flesh and blood and anxiety – our family, your children, we who hold your memory close in our muscles, our nightmares, in the fragile capsules of our prescription medication, in the rhythm of our bad habits. I watched as your eyes lit up for the arrivals of my younger sister, then my baby brother. Until I learned that the joy had an age limit. And that as we grew older you could only reminisce wistfully about the times when we were small and couldn’t walk. You could only love us like this as babies, powder and babble without any questions, or anger, or expectations. The adoring, unquestioning eyes that had not yet learned how to read. Maybe this is the only way some men can love. Although there are some men who cannot even bring themselves to love babies, or puppies, or anything. Maybe because they are just so damaged. Or maybe we make too many excuses for them.

You loved dogs. But the ones we had kept dying – two in horrific car accidents and one beautiful aged bull mastiff, Otto, who was sent to the farm. The next dog, a Rottweiler puppy, was called Bismarck. Both were named after the semi-famous Prussian statesman who in my opinion reads like a prequel to Hitler and who amongst other things hated socialism, democracy and Liberalism. I think there was supposed to be some irony here. And then of course there was the time Max, the mixed husky you ‘rescued’, was stolen out the yard. That story is suddenly very different when written on the page.

Or maybe it wasn’t a problem with being able to love us, after all. Maybe it was your pride. Maybe you couldn’t look at us after you vacated your job, exiled yourself from the company of other creatures besides books and junk and homemade weapons. And then once you had cleared away the clutter of most people, slowly and it seemed almost deliberately, you started losing your mind. The leftover parts of which are incompatible clues. The parts of an inane machine. As we grew up and became all the more intimately involved with life, so you fell out of love with it and tried to keep yourself as close to dead as possible. As you could be now, alone. Partially cast out, partially yourself an outcast. A thief who has allegedly stolen from his own mother’s safe after being put up in her house, discarded his phone and made a run for it, without a trace. An alleged abuser, which is somehow more acceptable. There are no more members of your family who will keep you in their homes. I say ‘keep you’ as if you are a pet. A big man-pet, who cannot feed itself or wash itself but who will bark viciously at all the intruders real and imagined.

I don’t blame them for putting you out on the street. You’re the kind of damp that makes people’s houses fall apart, ceilings silently rot from the inside. The kind of damage that you can slowly get used to, mistaking gangrene for grass. You are less a plant than a broken mechanism. Rusty, archaic tool, blunt hacksaw, bent screw. I am not a naive and decadent young arts student anymore. Yet I fear there are still parts of me enamoured with the poetry of your tragedy, the lyrical complexity of you. You have always known exactly how to appeal to my creative fervour. I must try to remember you are a non-functional, un-aesthetic artefact that will not hang in the museum of anybody’s heart. Not a painting, or a dinosaur, or a work of literature. You’re more like a thick old phone book. Stuffed with the numbers of places that will no longer answer. People who can barely prove they were there to begin with. A paper wasteland, indecipherable hieroglyphs.

Some of these nights, combing through these pieces of evidence, I wake up shaking. From a childhood nightmare that still fits snug. That you will emerge and come and kill us in our sleep. Even though you would have no idea where we live now. Me in Muizenberg, my sister in Joburg, my brother and mother in a house in Observatory. Well, I suppose I’ve just given you some idea if you ever read this. And even if you did go back to the old house in Glenhaven, where my grandparents still live, the locks on the doors have all been changed and a K9-trained Alsatian guards their front gate. I’m not really actually afraid you will come and kill us. I’ve had these sudden and fast-dissolving fears not because you were physically abusive, but because you are terrifyingly unpredictable, now more than ever before. Now that you are no longer contained in the room at the back of the house where you never ventured beyond the kitchen.

The fear of you is more like being scared of a ghost. So I suppose searching for you is more like hunting for ghosts. And what I need more than an austere Famous-Five-style packed lunch is a strong sense of self, a proton pack and a particle accelerator. But men really didn’t like the women Ghostbusters. So who am I to revisit the narrative?

For an ex-journalist, you have left little evidence of your story. More a spectre than a body. And even though I haven’t had and probably won’t have it in me to really go looking for you in shelters or in the streets, you might be upset that I chose to write you down in this book. But you set the precedent that we should always meet most authentically on the page. And I’m a little scared that by putting together the right collection of words I might summon you back like a spirit. But there is nothing unique here, this is no new story. In my country, everyone is a little haunted by all the lost bodies. And nobody knows where to put them to rest.