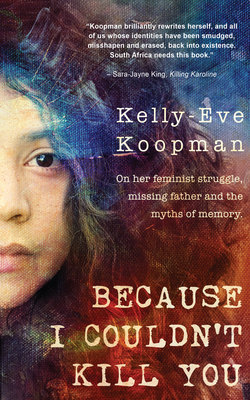

Читать книгу Because I Couldn't Kill You - Kelly-Eve Koopman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A brief history of sameness

ОглавлениеI have come to my childhood home. To fight fair with writer’s block on home turf. To pin down the evasive muse at the source of my creation, amongst familiar old ghosts, amongst the dusty artefacts of self, the porcelain dolls, the illustrated encyclopaedias, the well-worn single bed that will always recognise my shape. Here where I am brought coffee in a matching cup and saucer, and the sheets are quietly turned down in anticipation of a good night’s rest, where there is still white bread, and white sugar, and koe’sisters awaiting their turn to be syrupped and zealously rolled in coconut. This is why I am here, in the quiet of the suburbs that in my teens I could not wait to run away from. Glenhaven, a place where, at first glance, it seems that time has generously stood still.

This has been a coloureds-only suburb for about 45 years. Coloureds only as declared by the NP Government, a place which, like many places, has stayed exactly the same decades later. The first black and first white families moved in pretty much simultaneously when I was in my early teens, sending a minor shock ripple through the neighbourhood. Soon afterwards, because of Glenhaven’s proximity to UWC, the university that my mother dedicated her academic career to, there was an influx of trendy young black students sharing the well-priced, neat and secure houses. They walk through the streets at night, arms confidently linked, talking and laughing, and have parties with loud gqom music. While the area is home to people who recognise that it’s not good etiquette to be outright racists, there is the generic, familiar tone of othering when referring to the young black newcomers. There has also been a marked increase in the number of neighbourhood-watch-type WhatsApp groups and murmurs about ‘culture clashes’ – words that despite their best efforts can barely veil the implicit racism.

The neighbourhood has always more than tolerated the existence of coloured teenagers and 30-year-old baby daddies who, despite having mid-managerial level careers, never move out of the bed and breakfasts of their mommies’ homes. These youths who park cars outside the tennis courts and skelmpies drink in their dropped cars, recognisable by the murmuring bass of deep house (very similar to gqom but regarded with much more tolerance) or turn up in very clean and well-furnished yaadts when their parents are away on holiday to Club Mykonos, there by Langebaan, not to be confused with Mykonos in Greece – or in Thailand even, if your parents are those who have a double-storey house and a pool. The perfunctory trip to Thailand has become like the hajj of middle-class coloured culture, modest conspicuous consumption in the form of a Contiki trip.

These mildly disaffected youths are tolerated, there is the mutual understanding that these are kids under the firm hand of parents and grandparents, who are expected to for the most part conform to the code of the suburbs and move out to become accountants and HR managers, buy in the neighbourhood, move on to other respectable coloured suburbs, or perhaps even permeate the more gourmet vestiges of the Boerewors Curtain – the Durbanville Hills and the Stellenbergs, where the white Afrikaans Janse van Rensburgs will regard this new influx of unsightly coloured young professionals with the same attitude the Jacobs of Bellville South regard the influx of young black scholars.

My grandparents were one of the three first families to move into the area, the founding fathers, pioneers navigating the rough terrain from working to middle class. They started building the closest they could get to their dream house on a sandy vacant treeless plot flanked by the nylon spinners’ factory on one side. Safe and sequestered and still technically on land that was the Cape Flats, this was the perfect place to engineer their painstakingly difficult ascent into the brown middle class. My grandmother went to teachers’ training college – the pinnacle of a coloured woman’s education at the time was to be a respected Sub A teacher. My grandfather started off as a worker, quickly climbed the ranks as a factory manager and found himself gratefully able to afford living-room suites, Christmas presents and good educations for all three of his bright, lucky children. Their house, which they named Oasis, was the first one built on the street, ranch style with big windows, a gleaming stoep and a meticulously cultivated rose garden. The house lived up to its name, and almost every one of their children and grandchildren at some point, going through a difficult time, seeking some kind of refuge and release, has returned to its sturdy suburban walls.

I too return to write this book. I dare not spill my coffee on the pristine white cloth on the dining-room table, with small roses embroidered at the edges. I have a view of what was once the lawn but has now been recently paved. My grandparents, who have always been very attentive to their plants, have, after much deliberation, laid over the sparse, tufty expanse that has slowly succumbed to the inevitable dereliction of the drought. Across the road is the ‘parky’ which has managed to evade any kind of government attention and still boasts the same rusty roundabout and precarious tyre swings from my childhood. The sepia fragments of faded, broken Black Label and Brutal Fruit bottles are relics, abandoned by coloured teens who have now gone on to drink Merlot and buy Webers.

The neat, sprawling ranch-style houses and spilt-level bungalows overlooking the parky’s offensively disordered archaeology cast their eyes down in shame and disdain. This is a nice neighbourhood after all, and if it weren’t for the evidence of the parky and marked absence of trees, it could even be mistaken for a white area. The houses have heavy eyelids weighted down with netting and thick, frilly curtains that are meant to stop outsiders looking in, but do not prevent insiders from looking out. In the centre of the parky, squat and with a prowess that seems to defy the inevitability of power cuts, there is the militaristic-looking kragbox that I was always told was too dangerous to approach. It is lovingly decorated with the prerequisite graffiti, different names making declarations of love and loathing in different ways but always in the same font. The Helvetica revolution has not yet made its way to the deep North.

My grandfather is in Lenny Kravitzy tinted glasses to protect his eyes post cataract operation – he wears the tints for driving, which he does confidently at 85. He glances at my coffee cup and my uncapped pens, which I realise are a danger to the piety of the pristine tablecloth. I ask him what he’s doing today and he simply says he is ‘at your grandmother’s disposal’. He has already taken her to the hospital for a check-up – she recently had her second hip replacement – and is currently helping her spoon jam onto rows of gravity-defying scones (the secret ingredient is plain yoghurt) and will shortly be driving her to her Women’s Meeting at the church. Of course, women of the faith have different issues than the men and I sometimes imagine they are plotting to overthrow the religious patriarchy over lamingtons and rooibos. He will fetch her as soon as the meeting is over, they will take an afternoon nap together, she will make sure he takes his heart medication, make sure the clothes and house are clean, and buy him new socks when the old ones sink into his shoes like ‘tsotsis’. Theirs is a marriage pegged on quiet and dedicated acts of service, and acute attention to detail, a beautiful exchange.

The sounds of devout industry emanate from the kitchen – my grandparents are firm believers in the ‘idle hands’ philosophy as well as the ‘proximity of cleanliness to godliness’ maxim. I am grateful. I think the commitment to activity and the kind of reliable, consistent fellowship offered by the church has kept them relatively healthy and has added years to their cumulative lifespans. My grandfather is being accused of putting too much jam in the middle of the scones, ruining the delicate jam-to-cream ratio. He defers, promises to use only a level spoon. While conservative gender roles may seem concrete, whenever I am around them there are the glorious nuances that threaten the foundations of the heteronormative tradition. One day my grandfather sat me down and tried to explain the virtues of stewardship to me. I don’t think I understood. We have often had conversations around certain biblical chapters and verses. He has always been in love with the Lord and I once also shared this infatuation with the Bible. As a child I went to sleep clutching my special leather-bound King James, mainly because I thought nothing bad could happen to me or my family if I dutifully consumed verse after verse every single night. I especially believed that murderers from within or without could not come and savagely slaughter us if I was clinging to the word of the Lord (thanks be to God).

Above my head hangs the reproduction of The Last Supper, in the same position it always has been, as if to represent the exemplary art of dinner, complete with gossip and requisite backstabbing. Beneath the painting is the locked display cupboard filled with sets of function glasses, sherry glasses, champagne glasses, martini glasses, all displayed in a vehemently dry household. A household occupied by those who will always carry the trauma, the fear of the scourge of addictions, alcohol, drugs. The vice grips that could asphyxiate the dreams of stability and success in their infancy.

I am about halfway through this book, which is meant to be a memoir without a hook, a chronicle of a relatively ordinary life marked by some minor successes and the everyday. I am here to try and finish it. I have been sabotaging myself, actively seeking out distraction with the ocean, my partner, friends, Twitter and Netflix (I have already indulged in two pirated episodes of The Marvelous Mrs Maisel), things the house needs from the Checkers and the ubiquitous temptation of ‘just one drink’ with whatever friends I mercifully have left, considering my reputation for cancelling or forgetting about social plans, which even for a Capetonian is impressive.

It’s a Saturday afternoon. I’m still in pyjamas and trying to finish this sentence before my battery cuts out. Load shedding. I’m not used to Bellville’s blackout schedule and have been caught unprepared because I forgot to put the Bellville South area code in my Eishkom scheduling app. Usually I’d have my phone charged and my laptop juiced up. But today, having found myself in this unfamiliar intimate environment, I’ve been caught unprepared.

Here in the pristine, loving house I grew up in, amidst the gleam of furniture polish and the smell of baking, I am tempted to shut out the echoes of violence. This is a temptation I’ve had to resist since childhood. The longing to resist the residue of madness held close in the walls and the floors, no matter how many times they have been scrubbed, like the ghosts that will not be evicted from my heart, no matter how much I am loved. This is perhaps a place to begin.

Sunday morning, and my grandparents are on a post-church high. There is tea to be brewed, there are new koe’sisters to be syrupped and rolled in coconut, tidy things to be further tidied in anticipation of ‘visitors’. The visitors – a recurrent theme from my childhood nightmares, the distant relatives or church aunties and uncles. As kids, no matter how we tried to duck and dive, pretending to be asleep, or inundated with debilitatingly complex homework, we always had to go in for the powdery kiss, the obligatory report about our school marks, and the ever-present possibility of a comment about any perceived changes in weight or general appearance. If you didn’t ‘greet’, not only were you going to be considered a ‘rude’ child, the antithesis of a ‘good’ child, and risk bringing eternal shame and dishonour upon your family name, you also would not be given the milk tart, doughnuts and aforementioned homemade scones with the secret plain yoghurt ingredient. Under the worst of circumstances you might be expected to ‘sing for the people’, recite something or regale the company with tales of certificates, A pluses and all other preadolescent accomplishments. Luckily I have outgrown this phase and am no longer expected to stand on the dining-room steps and sing, but I am expected to be clean, presentable and follow through with the liturgy of the visit.

The ‘visitors’, apart from maybe a handful of mean-spirited old women and particularly patriarchal gentlemen of the clergy, are generally very nice people. And more than the actual visitors themselves, the rites of the ‘visit’ have given this good Christian ritual its sinister, occult status. This is why as soon as today’s ‘visitors’ arrive, family from abroad, I hurry to complete the perfunctory kisses, am told I am looking ‘more and more like my mother’, and then abruptly rush into what was once my childhood room. Before I put my headphones on, I hear fragments of conversation through the walls. One of the visitors, an uncle-in-law who I have maybe met twice in my life, is a respected minister with a PhD in theology. I hear him use the phrase ‘race card’ and am happy to be exempt from a no doubt virulently racist conversation, thinly cloaked under the vestments of neo-liberalist politics. If the good minister was my Facebook friend, he would have found himself blocked.

They have moved on from politics to religion. I can’t say I’m relieved. I hear the beginnings of some kind of proverb. Proverbs 31, Verse 10, to be exact. The acoustics of the house, with its wood and tile floors, means you can eavesdrop on conversations pretty successfully. He starts speaking and my skin crawls a bit in recognition of the tone. He speaks with the unmistakable authoritarian tone of preachers and pastors afflicted with lust for the power of the pulpit. It is a convivial yet paternalistic and chastising cadence often deployed to deride women in some way. ‘Who can find a virtuous woman?’ he says. ‘For her price is far above rubies.’ The rest goes a bit fuzzy, until his voice rises again, delivering the punchline... ‘a good woman is a woman who doesn’t talk out of the house. ’ There it is. Not verbatim from the mouth of the Lord but it might as well be.

I know this lesson well enough. Good women do not talk out of the house.