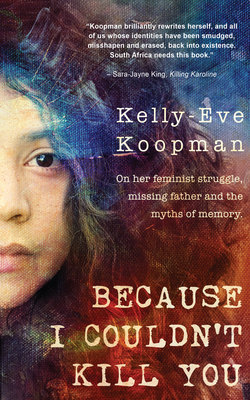

Читать книгу Because I Couldn't Kill You - Kelly-Eve Koopman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Do dinosaurs have feathers?

ОглавлениеI feel like I’m at the beginning of a quest. A good time to write a book, I suppose. This is what Sarah, my sage-like girlfriend, has told me in her eponymous introspective way.

‘Don’t rebuke the hero’s journey – you’re writing this book, you’re on a quest, why not start with that?’ But the model of the hero’s journey does not feel right for my quest. I try to hack through the bog of Western references to find a different model for my quest. I don’t know enough of my own African stories – I have not learned the methods of oration that belong to me. I settle on ‘What you seek is seeking you’. Wisdom from the Sufi, and unfortunately one of the most overused Rumi quotes, mercilessly pushed into the realm of cliché, thanks to internet memes, Instapoetry ardently consumed by millennials like me and of course the white middle-class obsession with appropriating Eastern spirituality.

I suppose I am looking for something. But I don’t even know what I want to find. ‘What you seek is seeking you’: except when it’s your unhinged, abusive father who has predictably never paid a cent of maintenance. His name is Andre Christian Koopman. Wanted Dead or Alive. If you know his whereabouts, tell him he owes me reparations.

What I seek, or rather what I am possibly considering seeking, puts me on a particularly morose and most probably unrewarding ‘choose your own adventure’ type of narrative. By process of elimination I have already concluded that this story will end with the following possibilities:

a )My father is dead.

b) He stole money from his mother and/or his mother’s NPO and therefore does not want to be found.

c) He has become more mentally ill and is homeless and/or needs to be institutionalised.

d) He is as happy as possible under the circumstances and lives in some kind of torrid but safe commune with other displaced individuals with unresolved pasts and uncertain futures.

Should I decide to act, take up the quest? One of the above will be the prize of my valiant efforts, requiring exhausting emotional labour to find this person who left most of my childhood and teenage years scarred and bruised and filled with agonising unanswered questions. Memories that have ugly, misshapen holes like cigarette burns. Voids of time that got sucked away in a house that harboured a somnambulant psychotic, a man who was so easily triggered to rage and strange, virulent anxieties.

Even if I were to do the things we misname as healing and exorcise my assortment of daddy issues, through the idealised mixture of therapy, vigorous physical exercise and perhaps some kind of exclusive esoteric practise – involving excessive amounts of sweating, an appropriated tribalistic drum and a matching Adidas two-piece, of which variety there are undoubtedly many in Cape Town – there are still the genetic attachments, depression, anxiety disorder, pathologies and pathways that unmistakeably carry my father’s family name.

I look like him. My body cannot purge the evidence of his existence. I have the impressively thick and dimpled thighs, the dark, thick bushy hair that grows conspicuously all over me. Hair that sprouted way too early and made me feel less like a girl and more like a kind of strange animal. I was maybe about eight when a particularly astute and unkind boy, noticing my excessive hair and excess body weight, started calling me a woolly mammoth. Mercifully, the name never stuck, and was abandoned after he taunted me with it for a few weeks and I tried to show him that the words bounced right off my thick woolly skin. But sometimes, even now, I look in the mirror and recognise at once my strange, monstrous father combined with vestiges of that great Pleistocene beast and I wonder how much of just me I really am.

I never thought I would go looking for my father. I had thought I had left him behind. I thought that the smudgy shadows of him might be abolished as soon as I washed them off the walls through therapy, through conversations with my partner, my mother, my sister, my partner some more, asking questions, uncovering a myriad of suffocated years through the process of breakdown and resuscitation, of personal truth-telling. I had fallen into that naive and damaging belief that the excavation of my truth would mean my own inner reconciliation. I thought I had left him behind. But every time I am emotionally intimate, every time I make a bad decision, every time I am inspired, every time I come to the page – I am leaking, wading through this flotsam and jetsam of him. My body feels swollen with the retention of this flood of feeling, of rage, of hurt, of a reproachful and reluctant empathy. On the days I think of him too much, it is as if I am turning to an essential source for my own analysis, an important intersection of my own veins and arteries – me, the bloody, messy map of genes and generational experience.

It has been roughly eight years since my father was exiled from our family home and vacated my life. Most days I can look at him from a distance, more closely, more fairly than when he held me hostage in the house, roaming the passages throughout the night, at once protecting us from danger and inducing our nightmares. Except for the times I see him when I look in the mirror, the distance has made me view him as if neatly framed and mounted on the dense white walls of my cranium as ‘The Portrait of a Post-Apartheid Black South African Man’. I say black because my father would never have identified as coloured. The Molotov of toxic masculinity meets PTSD and broken dreams. Now, with insight into the intersections of trauma, untreated mental illness and unfettered ego, I can read him as a splayed-out, bloated, unwashed Vitruvian man. No longer the foggy chimera of my childhood, the creature that lurked at the back of the house and would come out every now and again in grotesque forms.

These are the ways I now conceive of him. Often in therapy, in my relationship, in my own process of self-analysis, I try and remember specificities. I attempt to pinpoint who I was, who he was, trudging through the fog of childhood to make some kind of sense, to excavate an enlightening moment. I ask my siblings what they have held on to from our childhood. My brother cannot recollect anything that happened pretty much up until his preteens, an erasure that is an act of self-preservation.

My sister cannot afford to remember, another act of survival. My mother, despite being a university-trained historian, can offer me some things but they are mired in her own feelings, her untouched pain, her infallible desire to forget and move forward. My grandparents, although eager to share old photographs, anecdotes and oral history, do not know how to talk about these things. The things ‘good women’ don’t talk out of the house about, right? The dirty, bloody laundry, which with this book I am not only hanging out to dry but leaving to stick between the pages.

So I try and fill in the gaps. Piecing the skeleton of my personal history together with broken evidence. Like an archaeologist who, from the safe distance that time allows, can cast the bones of the prehistoric creature, no longer terrifying. But even then, when relics and fossils are lovingly and painstakingly pieced together and studied, the theories we build around these can be vulnerable to conjecture. And we curate the museums of our past with wilful subjectivity.

A few months ago Sarah and I had the privilege of going to a conference in London. I wanted to hate this trip to the colonial motherland, but in spite of myself, the fucking behemoth of a city charmed me with its chic gloom and edgy, ubiquitous art. With the pound exerting its tyrannical colonial weight over the feeble rand, we aimed for as many free activities as possible. Luckily there are incredible museums. We tried to avoid those that we knew for sure were filled with stolen things, which cut out about three quarters of them. Around the time we were there, Sarah showed me an article about how leadership from the Easter Islands had travelled to visit the leadership of the Victoria and Albert Museum to urgently appeal for the return of an 8-foot basalt Moai statue known as Hoa Hakananai’a (‘lost or stolen friend’). Moai are defined as the living faces of deified ancestors. The governor of Easter Island responded to this capture and display of his ancestors with the plea, ‘You have our soul.’ This line, ‘You have our soul’, was the headline of the newspaper article. In response to this, the Victoria and Albert Museum agreed to possibly, maybe, loan the statue back to the Islanders.

To avoid complicity in this hubristic display of inhumanity – and armed with the knowledge that in most museums, there are trophy bones, even if not on display; there are the frontal lobes from skulls prised open for all the brain matter and thoughts and dreams and memories to spill out; there are the eyeballs and sex organs, reveries, histories and desires of the vast and varied indigenous people hidden and pickled in boxes and jars in museum basements – we stayed away. Instead we flocked to the modern art exhibitions (these are safer to visit as a colonial subject abroad although not necessarily safe for women, considering the predation of so many modern artists) and the Natural History Museum, which we hoped housed only the bones of long-dead animals.

The entrance to the museum boasts the shell of a massive Brachiosaurus, safely enclosed behind a glass cage. Just a few paces on, there is the majestic framework of a Tyrannosaurus rex; a short left reveals the dead monsters of the deep. They make an incredible pantheon. We were at first unsure whether the skeletons were real. I felt like I was in the presence of gods. At some points, walking between the glass cages, awestruck, one of us murmured: ‘You know, it’s very possible they all had feathers.’ I am not sure whether it was me or Sarah. We are very similar and we share thoughts generously. Sometimes the lines get blurred and I feel like I am absorbing her knowledge and saving it to my hardwiring as if I was one of her cells or one of her senses.

Although most of us have grown up with the notion that all dinosaurs are covered in skin resembling scaly reptilian armour, it’s very likely they could all have had feathers. Somehow a gigantic bird, even armed with guillotine teeth, is less scary, or perhaps just entirely different to the tyrannosaurus we all know – the dragon scales, the tiny, inept Trump hands, the wide open mouth.

If you google a picture of a Tyrex, it is always depicted with its mouth wide open, ready to decapitate something with its massive mandibles. The entire species has been memorialised in a permanent state of aggressive screaming. Because it was a perpetually violently predator, probably. But what if it was an existential scream, a Munchian scream even? Maybe the Tyrex was always hungry because it comfort ate, stuffing its face with woolly mammoths, hating itself the next day. Or maybe somewhere in that tiny lizard brain it was aware of the incoming meteor or whatever it was that killed the earth. Maybe it was running around and screaming in terror, the rest of the planet deaf to its unintelligible, raspy cries, like an environmentalist in the early 90s, prophesying the impending planetary meltdown.

Nobody knew how it lived, nobody knew how it died. We can infer, we can empathise and glamorise it, and put its mammoth bones behind the glass cage, and emblazon its alleged likeness on book bags and trendy restaurants, and know nothing of its world, its self. My missing father, my deadbeat dad, is the Tyrannosaurus rex of my personal historical timeline. Remembered mostly as violent and brutish, but also as an elusive and fascinating villain that I don’t know if I have the expertise or evidence to dissect, piece together and truly understand.

In the process of writing this, as I wade through the varied landscapes of my memory, I wonder: What have I re-sketched, what have I missed about my father? What have I gotten wrong about him, my family, about myself, about South African history, about the world, about everything? Does my dinosaur have feathers?

I was in my final year of varsity when my mother finally divorced my father, after acting for over a decade and a half in that dangerous dual role of his caretaker and his wife. Finally, in a moment of enlightenment, she realised that she did not need to prove her worth by saving a person who had no interest in being saved, and she kicked him out of the house. Nobody missed him. The reason she finally managed to leave him will always remain somewhat evasive, but he was becoming increasingly aggressive and my mom says she just reached a tipping point. A point she wished she had reached years before.

I had already left the house to study theatre, a choice nobody unfortunately dissuaded me from. I lived in a Stellenbosch residence that was the Afrikaans version of a white Episcopalian sorority with a Southern plantation aesthetic and a whole lot of Jesus devotees. I hardly saw my father during my varsity years, partly deliberately and also because he was mostly hibernating in his mangy corner of the house when I went home to do my laundry. When she finally left him, I felt happy for my mother. I had spent a significant portion of my adolescence enraged that she wouldn’t leave him, convinced that her leaving would prove that she loved us instead of him. But the divorce did not give me clarity, although I felt good for my grandparents, who no longer had to harbour chaos in their otherwise meticulously ordered home, and I felt especially relieved for my brother and sister, who would not have to spend their adolescent years as I did, covering up the presence of a mad and violent parent who lived like a fugitive of time.

After the divorce my dad and I texted once in a while. The interchange was irregular and sometimes obscure. But still, this was more communication than we’d had in the last few years when he lived in the house. I was older, I had had my own confrontations with depression and anxiety and my political understandings of the evils I would later come to understand as structural violence. I was developing an empathy, a curiosity about the strange antagonist of my childhood. Sporadically violent but sometimes unpredictably tender. Knowing that I would mercifully never have to come home to the mess of my father again meant that it was way easier to try to connect with him.

He understood that it was his responsibility to seek me out first. So every couple of months he would send me heavily loaded messages filled with book references, sprawling philosophical titbits curated especially for me. I was about 19, I considered myself clever and deep. I was an arts student learning about Godot and the Greeks. His strange literary references and poetically articulated thoughts appealed to my artistic ego and my burgeoning interest in existential crisis. So sometimes I’d message back. Once I sent a casual, tentative ‘What are you doing these days?’ He responded with a single word: ‘Pining’.

We saw each other a few times in this brief period during my late teens and met once or twice for a cup of cheap coffee. These meetings were scattered and erratic, and short. Of course I did not trust him. I just wanted to know him. Sometimes things seemed promising, but each time I got a little hopeful about the possibilities for real reconnection, I was reminded that this was naive and self-harming and harmful to the people I cared about. If I opened up a little too much, he would take advantage, artfully request favours, ask for money, demand things emotionally that I could not give. My father was not going to change. He was not going to heal, he was always going to hurt us. No matter if I needed more from him. No matter if I wanted more for him.

One day, perhaps the fourth or fifth time we decided to meet up, we were sharing a piece of cake. We were speaking about nothing in particular when he said, ‘You know, if it wasn’t for that day and your sister, things would still be OK.’ On the day my mother finally kicked him out of the house, he made it clear that he blamed my sister, then about 12, for finally putting the end to their mangled relationship. Never mind the years and years of his mental deterioration, neglect and abuse. I had no idea that, all these years later, he actually still believed this story. I thought that blaming my little sister was just a deflection he had conjured up in a moment of weakness and denial when he realised he was finally being given the boot. We had an argument, although I don’t think he took it very seriously because he still asked me for money for cigarettes when I asked the waiter to bring the bill. I had to pay.

We didn’t speak for years again after that. I thought it would be the last time we saw each other. It should have been the last time we saw each other.

About three years later, when I was 23, we reconnected again and I hesitantly introduced him to my partner Sarah. Upon realising that we were going to be so significant in each other’s lives, we thought it would be a good idea for her to be introduced to the man who so clearly lurked in the corners of our intimacy, the obvious source of my cloistered emotional unavailability and dissociation and perpetual anxiety – these quiet mental illnesses that to the untrained eye could pass for ‘quirky’ or ‘hard working’. Sarah is patient and committed to this purging of secrets, of shame and shadow. She is a lover of the light even when it is scorching and blinding. She made me want to let her know me. She needed to meet my father.

We all went for a drink in Long Street, at Neighbourhood, which has since closed down. Not too fancy, not too grungy. My father has not had a job in the past 20 years, I knew I would be paying. I was nervous. Sarah was wonderful. Although she has a different life story, she has been to similar places in her mind as he has. She saw him and perhaps understood the suspension of living between two worlds, the artistry of sanity, balancing on neurochemicals and memory, strained cords of brain and heart matter, the tightrope dance that leaves you always constricted, always on tiptoe, or dangling from the rope with bloody fingers, or falling straight down into the porthole to those other worlds or into the sinkhole of depression, then wrapping yourself between the covers to protect your porcelain frame, shattered into a million pieces from the agony and ecstasy of the fall.

We made polite conversation for a bit. He asked about my life, our lives, genuinely and with warmth. We listened to his stories about his life, about his goals, the social development projects he was allegedly busy with. There was nothing concrete or tangible in anything he spoke about. I can’t even say he was lying. Because I know how resolutely he believes his own stories.

Then he started passionately talking about how he had started his own one-man vigilante neighbourhood watch in the road where he lived. This story was unfortunately true. He was staying in his mother’s house in Belhar, where he had been relegated from the main house to the garage. Most likely for bad behaviour. He whipped out his phone and proudly showed Sarah some grainy pictures on the cracked screen, evidence of him apprehending an alleged burglar. I guess he was trying to impress her. She looked politely. In the blurry picture my father stands over a teenage boy like a trophy hunter with a fresh kill. The boy is on his knees, looking straight at the camera, his hands bound together with black masking tape.

My father used to get up in the middle of the night on bin day to check that there weren’t murderers hiding in the bins on our street. My father used to pace the corridors of our house at night warding off thieves and monsters and murderers. I used to wake up to the sound of his incessant pacing, or to him standing at the door, watching over me as I slept. But he was far more frightening than these invisible threats.

Soon after he showed us this picture, we decided it best to leave.

This was the penultimate time I saw my father. It was death that brought us together again. About two years after our meeting in Long Street, my aunt, his youngest sister and a close relative we were all fond of, was dying in hospital due to complications from the severe cerebral palsy she had lived with her entire life. We visited her, Sarah was there to hold me again, and my father was there. Allegedly he was there all the time, and had been there for her, loving her fiercely throughout those last days. We three went down in the lift for a smoke break. He offered Sarah a hand-rolled cigarette. I wonder if he still smokes cherry tobacco. We offered him our well wishes and even a stilted hug. He held onto me too firmly. I hated it. He vaguely complained that I always gave sideways hugs, that I was restrictive with my body. I wonder why.

A few weeks after that hospital visit it was my aunt’s funeral. She was not old, midway through her 40s. She had exceeded the life expectancy handed down many times by numerous abysmal doctors. She was a fighter, a survivor, having suffered a lot from her physical disability. Her young lungs and organs were being crushed by her bones. Still, she did not want to die. When we went to the hospital to visit there were assembled family, religious men, baked goods and Bibles. There were fervent prayers and what felt like a constant, macabre mantra from someone in the room: ‘you’re ready to go to Jesus now’.

My aunt shook her head. She was not. She most definitely did not want to go to Jesus. She wanted the people around her to believe she could survive, as she had her whole life, despite her debilitating condition. It felt so wrong, seeing someone holding on to whatever life they could, willing their lungs to breathe despite the agonising pain, and instructing them to accept death. To hold up the opaque idea of Jesus over the aching reality of breathing, love, struggle, pain. Able-bodied people have this way of making decisions for disabled people. About what they must do and even who they are, casting disabled people either as living martyrs or infantilising them as inept innocents, incapable of desire, of dissent, of power, of personality even. I realised, as my aunt lay living, that in the time I spent with her as a kid (when my parents were together and we had good relationships with my father’s family), it was always with the implication that this was something good to do, in the same way I knew it was ethically sound to care for the quote unquote ‘frail’. I’m referring here to the neo-liberal framing of the 90s, where we saw ableism as virtuous and feminism as girl power. And while my aunt was always nice to be around and I think that we had nice enough visits, it never occurred to me to find out whether she even liked me. Whether she’d rather be doing something completely different than being read to or being made to deal with the probing small talk of a sanctimonious little girl almost 20 years her junior.

My aunt who did not want to die was loved by many, including her friends at the organisation my grandmother had started where people of all ages with cerebral palsy met up a few times a week to make lovely, functional art. And while I have given everyone in that hospital room flack about the obscene ‘Go to Jesus’ sentiment, it would be crude not to note that my paternal grandmother, in a time when it was near impossible to have basic healthcare rights as a second-rate citizen, tirelessly campaigned for disability justice and with her own funds set up a long-running project that benefited not only her own daughter but many others living with cerebral palsy.

Over the years the various homes of both immediate and extended family have been gifted these lovely creations, colourfully painted and textured mugs and plates and cups. When my father left our home, we found packed ashtrays, old newspaper guns, homemade weapons, a panga. Not sure whether these were meant to protect us or kill us, or both. The eclectic collection of crockery, painted by my aunt and prized by my father, was one of the few uncomplicated pieces of evidence of his occupation of the domestic territory he left behind.

I specifically asked Sarah not to come with me to the funeral. I wish I hadn’t. At the end of the service my father was tasked with the responsibility of thanking everyone who attended. He was so evidently distraught that it seemed perversely voyeuristic to look at him, with his insides exposed like that. A grimy peak cap overshadowed his eyes, the lilt of liquor and/or a tipsy proximity to madness in his walk. I became filled with dread, realising the endless possibilities for havoc in that stride. As he approached the podium my mother glanced at me with the same look of foreboding. There was no stopping it, all we could do was watch. From the front of the church, he addressed the assembled crowd of sniffing elderly and friends and family as ‘comrades’, the speech, lengthy and complicated, part obit, part call to action.

I looked at my mother’s face as soon as he started with this mention of ‘comrade’. She was looking up into the mid-distance with what was unmistakably empathy, compassion, the love you see fatigued mothers somewhat reluctantly but intractably hand over to particularly wayward children, kids who are addicts and relentless self-saboteurs. Love that they are not sure is good for either party involved. She could still hold out such love, any kind of love, to this man on the podium, preaching politics in the faded peak cap. The only partner she has ever had. A man who had been her singular reference point for love, for intimacy, the man who had abandoned her to the responsibilities and cruelties of the world, leaving behind an aching, stinking husk of flesh to be washed, fed and feared.

After the funeral we were all expected to go and have the perfunctory tea at the kerksaal, with the family. My aunt was down from London, we hadn’t seen her in years. We were beleaguered. Quietly suffocating under the weight of mourning and the spectre of our father, a spectacle that evoked in us all the nauseous nostalgia of the rambling discourses he performed during our childhood. He approached us, hugging us affectionately as if nothing had happened, neither the years of estrangement nor the rousing speech, as if he could be absolved by the devastation of his grief, as if this was enough to erase everything in the moment because he needed to hold on to us. I felt for him. My brother exiled my father from his gaze, took a step forward. He had to look away quickly, so he would not turn to salt. So he would not with his entire manhood ahead of him become locked in stasis at the sight of a depraved, burning fatherland, hypnotised by the flames. My brother has made it clear over and over again that he wants nothing to do with my father. My father is everything he wants to forget and everything he cannot let himself become. Luckily he is able to turn away and never look back.

My sister, at the same time, is becoming an acrobat. I can almost feel her muscles go rigid. She must make herself balance, her volatile brain chemicals, the restless throb of her sore little heart threatening to push her off the trapeze. I can feel all our muscles tensing up, the time travel down those neural pathways that have protected us, fight or flight, avoid, block your ears, stop drop and roll away into your room and slam the door. Being anywhere near my father’s nuclear reactive presence unlocks these other versions of ourselves with these latent emotional superpowers, shield, force field. I, the eldest, must step forward. I greet, I offer a condolence, sincere. I do this, I speak, I diplomatically shake hands, not because of my own morbid compulsion, not because I am a sell-out, but so that they don’t have to. At least that’s what I tell myself. We wave goodbye outside the church filled with mourners in black with tear-stained faces. I watch the top of his dirty greying cap and the back of his khaki flap jacket as he walks away across the parking lot, in the opposite direction from the small assembled crowd.

After the funeral, we are quiet. We all go straight home. Nobody has space for koe’sisters and condolences.

By the next funeral he has disappeared. My cousin, my father’s younger brother’s son, age 22, tragically fell to his death from a balcony in late 2018. My mother went to this funeral. I did not. My father’s absence was palpable. Nobody in the family had seen him for about a year and a half. In the years since being rendered houseless he had drifted between family members who had tried to accommodate him for as long as they could, until he became so damaging he threatened to make the walls and foundations of their own homes come crashing down.

After the church service which, according to my mother, was tragic and desolate, there was of course the obligatory kerksaal tea. My mother connected with the mutual friends and family members who do not avoid her. And overheard my grandmother, in response to the genially masked question, ‘Where is Andre?’, explain to the assembled collection of vultures and extended family that my father had ‘gone overseas’. A holiday. A long business trip. A business trip meets holiday, somewhere nice. Only the First World or a tropical paradise for the prodigal son. My mother understood this to be her cue to leave. She, functional responsible adult, single earner, the mother of his children, was a liability, a messy reminder of a dark and fatalistic reality. We do not really speak to this particular cross-section of my father’s kin and co-conspirators anymore. When my mother divorced my father, when we started cautiously acknowledging his madness, his abuse, instead of moving closer to us they moved further away, as if we were tainted. My mother has been denied her pain too many times over. It’s no new story. Men are exiled to tropical islands and women must stay behind to be ignored or become punching bags for skinner and ill repute.

My mother tells me this story about the funeral gossipers with incredulity, with disdain even, but without any visible evidence of rage. We’ve been speaking about it a lot lately, my mommy and I. Now that it has become clear that he is missing. Definitely not ‘overseas’. Sarah again generously has offered to help me track him down. To visit the homeless shelters and institutions, to fill in police paperwork, to prepare for the emotional damages of the process, to prepare for the myriad possible devastations of whatever we might find. ‘We’ makes it easier. The way she loves me is bold and in resistance to artifice, it requires emotional excavation, the revealing of both the beautiful and the vile. It is a life-altering and terrifying kind of love.

Coincidentally (or not), during this period, a little while after the funeral I receive the hero’s call to action. My uncle, my father’s brother, a kind man who I haven’t seen in many years – the same uncle who is mourning the untimely death of his son – sends me a WhatsApp. ‘I am worried about your dad. Haven’t seen or heard from him in over a year. Don’t know if I must report him missing. Any advice from your side?’ I don’t know. To seek or not to seek. To go chasing after ghosts. What you seek is seeking you.

There is nothing about my father that can be simply answered. As much as I resent the families I come from for covering our deepest wounds with the gauze of convenient truths, I understand the complexities and vacancies the name of my father invokes. On those days I think about him too much, a lot of what I come up with is fog and mist, a deluge of murky questions. What is wrong with Andre? This is the one that has been wedged in the silences we preserve between us. Schizophrenia, multiple personality disorder? A toxic sense of self-importance? An accumulated compendium of trauma and disjointed dreams that simply jammed the system? Also, why have the adults never set aside the protection of their own virtues and driven him to a mental institution, instead of harbouring a dangerous fugitive from sanity in a musty room? It would have saved everyone a lot of pain. But people have different ways of loving, and surely as an entire nation we are only now learning the dangers of forever living in hope.

There are always the questions. Who was he truly? What was wrong with him? Was he in the MK? Or was this a rumour? Nobody was sure. A skilled fighter, it seemed that he knew his way around weapons and vice grips and he certainly had the ideology down. He was always ready for the thief in the night, the assassin, the external threat, the markers of PTSD as distinctive as indelible Purple Rain. Once, I guess I was about nine years old, we were on holiday at Club Mykonos on the West Coast, the imitation Greek village that is ubiquitous of Middle-Class Coloured Kids. We were carrying our bags up to our newly clean chalets. It was a little after dark and there was not much light in the faux fishing town. Andre, my father, at this point could still leave the house. I came up behind him and tapped him on the shoulder to ask a question. I used to think he was the cleverest person on the planet.

He whirled around in boxing stance, ready, heavy hand thrust out to be aimed at an assailant’s throat. I was still smallish, at least not thug- or assassin-sized. I dodged and the blow went just over the top of my head. He cried out when he made out the shape of me in the dark. Daughter not enemy. Later on, these lines became much more blurred, he believed we were all, children included, implicated in the insidious plot against him. ‘Don’t ever sneak up on me again,’ he said. ‘I could have killed you.’ Thinking back, this was perhaps an overly dramatic line, pumped up by the ego men attach to their physical strength, but it stayed with me. ‘I could have killed you.’

I remember the hand-inked tattoo on his wrist, I think it said MK like a token of remembrance. But it could have said AK, his initials, or the gun symbolising the anti-Apartheid struggle, which he promised me he would one day teach me to shoot. I can’t shoot an AK47, or any gun for that matter – I’d be a useless cadre in the revolution. My military training is only one of many discarded promises. He also did not teach me to ride a bike.

After a certain age I learned to stay clear of my father’s hands. But then again he was martial arts trained since childhood and had a reputation for adept physical violence. Always in resistance, in the pursuit of a noble cause. The mythology of this ‘necessary’ violence gifted him with a manly corporeal reputation that followed him around like a peacock’s plume. Except when it cost him his job. Allegedly he had lifted his editor by the lapels and thrown him across the room. (My father was a journalist at the time.) The violence followed him around like a black mark, like phosphoric ink. But when he started beating on my mother, comrade, lover, there was very little nobility in that. That was something nobody liked to talk about and so it went, if not directly opposed, uncelebrated.

His is an ordinary story. As much as he would like to, he will never go down as a hero. My mother was a teacher, my father, a journalist – two of the thousands and thousands of everyday people who would lay down their lives for the struggle for justice. He was an ordinary man and a weak man with a broken heart and a bruised ego. I believe he felt unjustly deprived of the iconography we bequeath to our favourite freedom fighters. The statues and street names that erase inconvenient details like wife-beating and family abandonment. Gilded histories that wax the past lyrical and solidify a solid gold future. Far from a back room of a suburban house filled with overflowing ashtrays, mouldy paperbacks and PTSD.

There are only more questions now. New ones. Old ones. Where is he now? Is he alive? Why do I feel this responsibility to hold on to him, to preserve him in my personal history, perhaps as compensation for his erasure from the larger histories? Am I scared he will be completely forgotten? Do I feel sorry for him that he is alone and unloved? Does he deserve anything from me, even my pity? And how do I know if what I am seeking deserves the onerous effort of the search?