Читать книгу 22 Walks in Bangkok - Kenneth Barrett - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

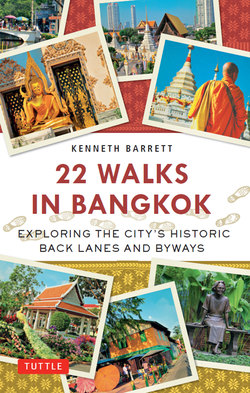

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Bangkok Begins

Brown as the earth it flows upon, warm and languid and sensual, the Chao Phraya River winds and loops southwards across the central plain of Thailand towards the South China Sea, a distance of 370 kilometres (230 miles), the alluvial terrain at its lowest point only 1.8 metres (6 ft) higher than the surface of the ocean. Across this fertile plain has moved a changing cast of people who have left scattered remains behind them, the earliest recognisable civilisations having been those of the Mon, the Khmer, and the Malay.

Around the seventh century a.d., the Tai people living in the mountainous regions of southern China began to move further southwards, away from the spreading influence of the Han Chinese, establishing settlements in the northern highlands of what are now Thailand, Laos and Vietnam. One group of migrants founded a town named Chiang Saen on the southern bank of the Mekong River, which rose to be a small but powerful kingdom. Over the centuries the migrants spread westwards and southwards, settling into the river valleys of the mountainous regions, founding villages and towns and kingdoms. By 1100 a.d. the Tai were firmly established at Nakhon Sawan, on the fringe of the central plain, where the Ping and the Nan rivers come together to form the Chao Phraya.

The migration of the Tai people into the Upper Chao Phraya Valley brought them into contact with the outer reaches of the Khmer empire. Centred at Angkor, the empire had spread westward across the central plain of Thailand, absorbing Mon kingdoms that had earlier spread into the region from Burma. One of these was Sukhothai, a trading settlement on the banks of the Yom River, the main tributary of the Nan. Sukhothai seems to have been loosely controlled by both the Khmer and the Mon at various periods, and possibly this is why the Tai were able to seize the city in 1238.

The Sukhothai era is considered to be the beginning of modern Thai identity, because for the two centuries it lasted this period saw an extraordinary flowering of power, wealth and culture. Within twenty years the kingdom covered the entire Upper Chao Phraya Valley. Under its third king, Ramkhamhaeng, the city-state adopted Theravada, the oldest form of Buddhism, as its official religion. Ramkhamhaeng also established the modern Thai script, basing it on the written language of the Khmer, which was itself derived from the very old Tamil script known as vattezhuttu, meaning “rounded writing”, which in turn was derived from the ancient Brahmi. The Buddhist and Hindu cultural influences that had originated in India and Sri Lanka and been propagated by the Khmer empire began to coalesce into a distinctively Thai form in religious art and temple architecture.

Sukhothai developed into an important trading centre, trading with China, India and the Khmer empire. As the city-state grew in wealth and influence, its reach expanded out of the Upper Chao Phraya Valley until it encompassed Lampang in the north, Martaban in Burma, Vientiane and Luang Prabang in Laos, and parts of the Malay peninsula in the south. This same period saw the rise of the Lanna kingdom in the far north of Thailand, as the Tai settlements in that region evolved. Based initially at Chiang Rai and then at Chiang Mai, Lanna was another great flowering of Thai culture. Relationships between Sukhothai and Lanna were largely peaceful. Lanna had more cause to fear Burma, a continual menacing presence, and the rise of the Mongol empire in China.

Against this background the founding of Ayutthaya, much further to the south, appears at first to have been of little consequence. There had been earlier kingdoms at this part of the lower Chao Phraya floodplain, and in the middle of the fourteenth century a man who was either a Tai nobleman or a rich Chinese merchant, and who is known to history as King Uthong, established himself on an island formed by the gathering of three rivers: the Chao Phraya, the Pasak and the Lopburi. Ayutthaya had two natural advantages: as an island it was well protected from aggressors, and it had easy access to the sea, just a hundred kilometres further down the Chao Phraya. Overseas trading had started to become significant, and the rise of Ayutthaya was therefore a natural development. It also happened fast. Ayutthaya was founded in 1351, and less than thirty years later had subsumed Sukhothai, which had begun to decline after the death of Ramkhamhaeng.

Ayutthaya became one of the richest and most beautiful cities in Asia and the most powerful kingdom on the Southeast Asian mainland. It also became one of the most cosmopolitan. The greatest volume of trade was with China, and such was the importance of the relationship that Ayutthaya entered willingly into a tributary relationship with the Chinese emperors. Chinese merchants and workers settled in Ayutthaya and many of them rose to positions of power and wealth. Muslim merchants came from India, and Japanese and Persians followed. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive, in 1511, at the time of their ventures in Malacca, and a year after they had conquered Goa. They received permission to settle in Ayutthaya in return for supplying guns and ammunition to the king. The Spanish arrived towards the end of the same century, followed by the Dutch and the British in the early seventeenth century. The French arrived in 1662, during the reign of King Narai, and their influence grew immensely when Narai and Louis xiv exchanged lavishly-funded delegations.

Despite the short distance to the sea, the meandering course of the Chao Phraya doubled the distance and meant that sailing to and from Ayutthaya took several days. During the first half of the sixteenth century canal works were undertaken at various points to improve navigation, and 1542 saw the most ambitious, a two-kilometre (1.24-mile) cut across a 14-kilometre (8.7-mile) loop that saved a complete day of sailing time. Rather than remaining a canal, however, the action of the river water widened the cutting so that it became the main course.

There had already been for many years a customs post and storage depot on the land within the loop: records from a century before the canal was cut referring to the official in charge as Nai Phra Khanon Thonburi, the earliest documented appearance of the name “Thonburi”, which can be translated loosely as “Money Town”. Now an island, the town gained in importance as a customs port, entrepot and garrison. Ships wishing to sail upriver were required to pay a tax there, and to deposit their cannon, which they would collect on the way down. A grand name was required for the now fortified port, and in 1557 it became Thonburi Sri Maha Samut, “City of Treasures Gracing the Ocean”.

The area through which the canal had been dug had, however, always been known colloquially as Bang Kok, or Bang Makok. No one seems to know which, or why. There are no Thai records, and the early European accounts give several versions of the spelling. Bang is the Thai word for a settlement near to water. Kok or makok is a variety of plum, so it is possible that orchards covered the area. There is some significance in the fact that Wat Arun, meaning “Temple of the Dawn”, was originally a small temple named Wat Makok. Another possibility is that the name was actually Bang Koh, which means “Village on an Island” and certainly, when the word koh is spoken, it is short and sharp, bearing little relation to the way it is written in English. There is even a possibility that the Malay word bengkok, which means “bend”, could have been borrowed to describe the meandering river. Quite possibly the name derives from all these sources. Whatever the origin, when the canal was cut across the land, the name Bangkok continued to be used for both banks and was entrenched by the Portuguese and all the European nations who followed them.

The origins of the word Siam evolved in a similar haphazard way. It is not of native origin. There is a Sanskrit word, syama, which describes a shade of dark brown, and a Hindi word, shyam, used for dark-skinned people. A twelfth-century a.d. inscription at Angkor Wat is the first written evidence of this word being used to refer to the Tai, and it has carried over to the Shan in Burma, who are of Tai origin. Early sources say that the people of Ayutthaya continued to call themselves Tai, and their kingdom Krung Tai, or “the City of the Tais”. The name Syam, Siem or Siam was propagated by the Portuguese, who possibly encountered it at Goa. Incidentally, the word “Tai” is not the linguistic root for the name of modern Thailand. The latter is a confection that dates from the 1930s, when the absolute monarchy had been overthrown and the new government was striving for an international identity that would also please the local population. “Thai”, it was decided, is generally held to mean “free”, while “land”, of course, is not even a Thai word. With more than forty ethnic groupings in the country, the new name was not universally popular, and there is even today a small but vociferous group of scholars who are lobbying for the name to revert to Siam.

The rise of Thonburi

With the main force of the river water coursing through the route of the canal, the original loop silted up and the waterway eventually became four canals: Bangkok Noi, Bang Ramat, Taling Chan and Bangkok Yai. From these, other small canals and streams connected and became the basis of transporting produce from the farms and orchards of the outlying districts. With the growth of residential areas came the building of temples. The garrison was strengthened in 1665 when King Narai the Great ordered the construction of Wichaiprasit Fort at the mouth of the Bangkok Yai canal to protect Ayutthaya from invasion by sea. Narai had greatly expanded relations with the European powers, which had unleashed an unprecedented foreign influence at the Ayutthaya court. Advised that a stronger French presence would provide a counterweight to the Portuguese and the Dutch, who were causing the most concern, in 1688 Narai allowed the French to increase their military presence at Bangkok, occupying the Thonburi fort and building another on the opposite bank of the river. A chain was laid between the two, which could be raised in the event of uninvited shipping attempting to travel upriver.

For the Ayutthaya courtiers, increasingly hostile to the foreign communities and to Narai’s chief minister, a Greek adventurer named Constantine Phaulkon, this was the final insult. The French were intent not only on trade and influence; they were flooding the city-state with missionaries in an attempt to convert the royal family and the people to Roman Catholicism. In what became known as the Siamese Revolution of 1688, the commander of the royal elephant corps, Phra Phetracha, staged a coup d’état and the king was arrested. Narai, who was already gravely ill, died a few weeks later. Phetracha became king. Phaulkon was beheaded. The Siamese then set to dislodge the French, who left the Thonburi fort and grouped at their new fortification on the open, swampy ground of the eastern bank. Cannon balls were hurled across the river at the French, and their fortress was besieged for four months. Eventually the French were ejected from the country, and aside from the ever-present Portuguese, who had largely intermingled with the local population, and a small number of Dutch traders, who had supplied material help, other European nations were no longer as welcome as they once had been.

The fall of Ayutthaya

King Narai’s era is regarded as the time when Ayutthaya was at its peak. After the dynastic convulsions that followed him had subsided there was a brief period of stability in the first half of the eighteenth century, but Ayutthaya’s influence was waning. The city-state had always controlled its provinces and vassal states with a relatively loose hand, and as a consequence many had become powerful in their own right and less inclined to be subservient to the king. Although the Khmer empire had been eclipsed by Ayutthaya, and the Europeans no longer presented a threat, the Burmese had risen in power in the middle of the sixteenth century and had overrun Chiang Mai and the Lanna kingdom in the north, where they stayed for two centuries. During the second half of the sixteenth century the Burmese had laid siege to Ayutthaya and captured the city for a brief period before they were driven out.

In the middle of the eighteenth century there were more struggles over the royal succession in Ayutthaya, amounting almost to civil war and culminating in the crowning of King Ekkathat. He was to be the last monarch. Ayutthaya had formed an alliance with the Mons who were fighting the Burmese, and in 1760 the Burmese attempted to invade Ayutthaya. Ekkathat, his kingdom weakened by internal turmoil, managed to repel them, but in 1765 they returned with enormous armies converging on Ayutthaya from both the west and the north, capturing peripheral cities to remove any chance of support for the capital. The Burmese laid siege for two years and when they broke through in 1767 they utterly destroyed the city, looting and burning its palaces, temples, libraries and houses. Ekkathat fled, and was discovered by monks in woodland several days later, dead from starvation.

During the siege, about a year before Ayutthaya fell, a Siamese general named Taksin managed to break out of the city with five hundred troops and he headed for the east coast, to Rayong, far away from Burmese influence. He was too late to save Ayutthaya, but at Chantaburi and along the eastern coast he built up an army of 5,000. With a land assault impractical, Taksin assembled a fleet of ships and sailed up the Chao Phraya to Thonburi, where the Burmese had installed a puppet governor. The Thonburi forces were overpowered and the governor executed. Taksin and his men sailed on up the river and drove the invaders out of Ayutthaya and back across the border into their own country. Ayutthaya was no longer habitable, and so Taksin as the new ruler had to make a very fast choice of location for a new capital. He selected Thonburi. There was already a thriving community, a port and fortifications, and the river and canals formed a moat.

Taksin’s kingdom

Taksin is one of the most remarkable figures in Thai history. He was part Chinese, his tax-collector father having been Teochew Chinese and his mother Siamese. The boy was given the name of Sin, and showing great promise he had joined the service of King Ekkathat. Eventually he rose to become the governor of Tak, a province in the north of Thailand that borders Burma. This brought him the title of Phraya Tak, or Lord Tak, and from there he became popularly known as Phraya Tak Sin. He was crowned king at Wang Derm Palace in Thonburi on 28th December 1768, at the age of 34.

Much of the new king’s reign was devoted to warfare. Several of the provinces in the east, north and south had broken away and were declaring themselves independent. Taksin waged campaigns against the rebels, he drove the Burmese out of Lanna, and he extended his power into Laos, Cambodia, and part of the Malay peninsula. Despite an almost continual state of warfare—and Taksin was a king and a general who led from the front—he still paid a great deal of attention to the transformation of Thonburi from garrison town to capital, renovating temples and building new ones, ordering canals to be dug, promoting trade with other countries including China, Britain and the Netherlands, and encouraging education and the arts. He brought in prisoners of war from his battles and used them as labour.

Craftsmen who had survived the destruction of Ayutthaya settled in Thonburi and formed their own communities. With China supplying money and manpower, Chinese traders thrived. The Portuguese, who supplied Taksin with arms and ammunition, were given a plot of land on the riverside. Indian and Malay Muslim traders established themselves along the canal banks.

Although much was accomplished in a short time, Siam was still in chaos. The breakdown of institutions and society proved a harder battle than retaking the provinces. Internally, the country was almost ungovernable. There were other contenders for the throne, and even the priesthood was in rebellion. Perhaps the strain was too much, for Taksin began to exhibit symptoms of mental derangement. He attempted to tame the priesthood by declaring himself an incarnation of the Buddha, punishing monks who would not worship him. He imprisoned, tortured and executed court officials who he believed were plotting against him, and certainly, with no royal bloodline to connect him to the old nobility of Ayutthaya, there were many who regarded him as a usurper. Morale in Thonburi sank to the point where, with the country largely held together by a mix of force and patronage, it was felt that the kingdom was yet again in danger of disintegration.

A court rebellion in early 1782 signalled the end for Taksin. Siam’s highest ranking noble, Thong Duang, more usually known by his title, Chao Phraya Maha Chakri, was away fighting in Cambodia, but he returned to Thonburi and rounded up the leaders. Chakri decided that the king had to be removed permanently. The generally accepted version of history is that Taksin was taken to Wat Arun, where he was placed inside a velvet sack and beaten to death with a scented sandalwood club, the traditional method of execution for anyone of royal bloodline, the belief being that no drop of royal blood should be spilled upon the ground. Another account says he was beheaded in front of Wichaiprasit Fort. A conspiracy theory of the time says that he faked his madness, as the country had become ungovernable and he was deeply in debt to the Chinese who had supplied much of the funding for his wars and nation building, and that he was secretly removed to a remote temple in the mountains of Nakhon Si Thammarat, where he lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1825. Whatever actually happened, the reign of King Taksin ended on 6th April 1782.

The Bangkok era

Chao Phraya Maha Chakri immediately proclaimed himself king, initially as Phra Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke, later becoming known as Rama I when the method of naming monarchs in this fashion was introduced by Rama VI. He was the founder of the Chakri dynasty that rules Thailand to this day.

Thonburi was capital of Thailand for only fifteen years, from 1767 until 1782, and Taksin was its only king. When Rama I came to the throne he was very much aware that the canal moat would not provide an effective barrier against a determined invasion by the Burmese. The area contained within the waterways was also too small for what was now a growing city. The king turned his thoughts to the land on the eastern bank of the river. There were numerous settlements and temples but they were scattered amongst the farmlands, orchards and marshy countryside. Directly opposite Thonburi the riverbank was occupied mainly by Chinese merchants and their godowns and the land was reasonably clear and dry, for the French fortifications had been extensive, and Taksin had already dug canals behind the merchant community for drainage and transportation. Enlarging these canals would form a protective moat and create an island. Predatory Burmese in the west would be kept at bay by the river, while to the east lay a broad expanse of impassable delta land known as the Sea of Mud. Heavy fortifications could be built along the river to discourage a sea-born invasion. Rama I could see that a city of similar grandeur to Ayutthaya would be able to rise from such a secure setting. The Chinese merchants were offered an area of land not far from their original settlement, and do not appear to have offered any resistance to the move. With a new capital city to be constructed on their doorstep they were probably delighted.

At the auspicious time and date of 6:45 a.m. on the 21st April 1782, the stakes were driven into the soil of Bangkok for the City Pillar, marking the official founding of the new city. Rama I gave his new capital a grand ceremonial name: Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Amon Rattanakosin Mahinthara Yuthaya Mahadilok Phop Noppharat Ratchathani Burirom Udomratchaniwet Mahasathan Amon Phiman Awatan Sathit Sakkathattiya Witsanukam Prasit. The longest place-name in the world, it translates as: “The City of Angels, the Great City, the Eternal Jewel City, the Impregnable City of God Indra, the Grand Capital of the World Endowed with Nine Precious Gems, the Happy City, Abounding in an Enormous Royal Palace that Resembles the Heavenly Abode where Reigns the Reincarnated God, a City given by Indra and Built by Vishnukarma”.

Foreigners, perhaps unsurprisingly, continued to use the name they had always known and which appeared on all their maps. Eventually Bangkok was registered as the official English language name. Thais call their capital Krung Thep Maha Nakhon, or more usually just Krung Thep, which translates loosely as “City of the Angels”.

A Buddha image in the grounds of a canal-side temple in Bangkok Yai.