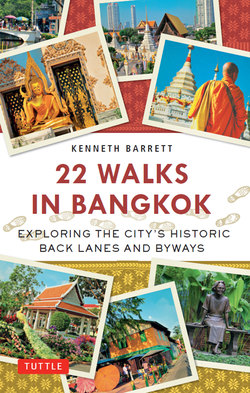

Читать книгу 22 Walks in Bangkok - Kenneth Barrett - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWALK 1

WONG WIAN YAI

In Search of King Taksin

Starting from Wong Wian Yai Skytrain station, the walk takes us alongside the Bangkok Yai canal to the temple that is the final resting place of King Taksin.

Duration: 2 hours

Once Bangkok had been founded as the new capital of Siam, Thonburi became something of a rural backwater. A place of market gardens and canals and old temples, it snoozed all the way through the nineteenth century as the Chakri dynasty built Bangkok into a powerful city. Only in the early part of the twentieth century did the world intrude again upon Thonburi, and even then it was to use the former kingdom as a transit point. The turn of the century saw the beginning of the railway era in Siam, and to service the south a line was opened to Petchaburi in 1903, later continuing down to Butterworth, across the Malay border. As there was no bridge across the Chao Phraya, a station was built in Thonburi, next to the Bangkok Noi canal, and passengers made their way across the river by boat.

For several years the northern and southern railway systems operated independently of each other, divided by the river. As rail traffic grew, however, the decision was made to build a bridge across the river and link all the lines at a new station on the east bank next to Chinatown. The Rama VI Bridge, opening in 1927 at Bang Sue, on the northern side of the city, was Bangkok’s first river bridge. Thonburi railway station continued to operate, serving local passengers and also the new railway line that was built to Kanchanaburi, in the west, but the southern railway line now bypassed Thonburi, looping around its northern edge. Five years later, in 1932, the second bridge opened. The Memorial Bridge carries the roadway across the river and has its Thonburi landing near to the mouth of the Bangkok Yai canal. Here, two traffic circles were laid out to link eleven new road projects in Thonburi that in turn connect to highways leading west, south and east.

With a suburban railway service and the laying out of the roads came commercial and residential development, and in recent years the BTS Skytrain has vaulted the river and planted commuter stations, but Thonburi has obstinately refused to follow the same style of growth as Bangkok. No central business district has evolved here, the only international hotels are a smattering along the riverbank, and the shops are for the locals. Thonburi remained officially an independent city and province until it was merged into Bangkok in 1971. Today, although Bangkok residents refer to the west bank in general as Thonburi, the name is officially affixed to only one small district, or khet, of which Bangkok has fifty.

Taksin and his brief kingdom could easily have been forgotten were it not for a revival of nationalism immediately following World War II., and the change of name from Siam to Thailand. Wong Wian Yai, the larger of the two traffic circles, had been a blank traffic island for twenty years. There is in existence a black-and-white aerial photograph taken in 1950, and the only features on the island are the pathways that cross it and what appears to be a tall lamppost in the centre. But the island stands at a point near the old harbour, and outside what had been the fortified walls of Thonburi, and Taksin would have mustered his troops on this ground. Part of the nationalist campaign during this time of great turbulence in Thailand, with a military government newly installed, a changed constitution and a great deal of popular unrest, was to rehabilitate the reputation of King Taksin. The government decided to erect a statue and place it in Wong Wian Yai. The statue was unveiled in 1954, and a ceremony of homage takes place every year on 28th December, the anniversary of Taksin’s coronation.

The first thing to be learned when taking the Skytrain across the river today is that Wong Wian Yai station is not quite at Wong Wian Yai: it is two-thirds of a kilometre away, being located on Krung Thonburi Road. The station steps lead down next to Bang Sai Gai canal, a small waterway that threads its way through this district. On the bank, and visible from the main road, are the red roof and white walls of the Chao Mae Aniew Shrine, a small and ancient Chinese shrine with a small stage in its courtyard for community meetings and performances. Hemmed in by timber houses with open verandas, this quiet setting is the first intimation of the pleasant rural area this must have been within living memory. The canal path leads to a dead end, the water disappearing under a low bridge, so a return to the main road is necessary, followed by a right turn into Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Road. Wong Wian Yai is directly ahead. Of course, long gone is the tranquillity of that old 1950 photograph, the king rising high above a sea of traffic, and pedestrians and advertising signs. Corrado Feroci, the Italian sculptor who spent almost forty years in Bangkok and is regarded as the founder of modern art in Thailand, has cast him in metal and placed him on a reinforced concrete pedestal some nine metres above street level. The king, brandishing his sabre in the direction of Ayutthaya, is mounted on his horse, or to be more correct a Thai pony, an indigenous breed that stands naturally at about twelve hands and which has the toughness and stamina for both military and pack animal use. The circle is a brilliant splash of colour, its gardens planted with red, green and yellow blooms, and the place is frequently lively with gatherings, for it is a focal point for local rallies and community activities. Around the circle is a large selection of shops, prominent amongst them the haunted shell of the Merry King department store, closed for many years now, the darkened entrance to its basement carpark the stuff of B-grade werewolf movies.

Just off the circle is Thailand’s strangest railway line. The Mahachai-Mae Klong line was built by the Tha Cheen Railway Company under a private concession and opened in early 1905, its purpose being to bring fish and farm produce from the coast. The trains run down to the Tha Cheen River, near to where it empties into the sea at Samut Sakhon, a fishing port also known by its older name of Mahachai. There is no bridge there so everyone disembarks, catches a ferry, and boards a train on the other side, which then goes further along the coast to Samut Songkhram, or Mae Klong. Both stretches are the same length, almost thirty kilometres. The line is completely independent of the national railway system and is a single track. Although Wong Wian Yai is the terminus, it is the most modest terminus that can be imagined, for passengers simply walk through a gap between two blocks of nondescript commercial buildings on Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Road, and the platform and ticket office is there, sitting next to the pavement. Railway anoraks love this line, as indeed does anyone who travels on it, because it is rather like a grown-up train set that winds its way out of the city and through the rice fields, orchards and plantations. They coo over its whimsical rolling stock and wayside stations, marvel at the occasionally wiggly rail lines, and hold their breaths during the rainy season as the little trains plough manfully through the lakes that appear at certain stretches, the line disappearing under the muddy water and no one being quite sure whether or not the rail bed has dissolved. The grand soul-sucking moment for everyone comes when the train eases into the centre of the market at Samut Songkhram, where railway and market are not easily distinguishable, the stallholders politely removing their produce from the sleepers and folding their umbrella shades to allow it through. The Thais have a wry sense of humour, and the market is known locally as Talad Lom Hoop, or “Closing Umbrella Market”. Despite its Toytown quality, the Mahachai-Mae Klong line is a hard-working one with a frequent service, crowds of commuters along with pickups stacked high with boxes of fish, fruit and vegetables regularly emerging between the two grimy buildings at Wong Wian Yai and adding to the general traffic chaos.

There is a narrow road that runs alongside the railway track. Liap Thang Rot Fai is almost rural, with old timber houses and modest brick buildings along the route, the clamour and traffic of Wong Wian Yai left behind within minutes. A lone foreigner trudging down this odd little country lane is assumed to be lost, and along with the smiles and waves there will be offers of help and even of food and drink from residents sitting in their gardens. A landmark on the right-hand side, not far from the station, is the Suan Phlu Mosque, marking one of about twenty Muslim communities in Thonburi, descended mainly from the communities that had existed in Ayutthaya or from prisoners of war brought back by Taksin from his campaigns in the east and the south. Off to the left is a maze of little lanes, with a few old and rather splendid houses behind high gates, a huddle of more modest dwellings, and a couple of neighbourhood temples. One of these, Wat Kantathararam, was privately endowed. There is a plaque on the wall outside that says the one-and-a-half acres of land were donated by a couple named Mr Kan and Mrs Chan in 1891, and that they and their children also contributed to the construction of the ordination hall. The family were successful farmers and traders, and when Talat Phlu station comes into view a few minutes later, the name indicates at once what this area was: a betel market. It was in fact the main betel market for Bangkok.

Talat Phlu is on the bank of the Bangkok Yai canal and can be traced back to the time of Taksin, when Teochew people who had migrated from southern China settled in the area. Farmers and traders, they cultivated plantations of piper betel, or phlu, which stretched along the bank of the Bang Sai Gai canal, the Bang Waek canal, and other areas next to waterways. Chewing betel was popular at that time, people using it during social occasions, as a breath freshener, and to blacken their teeth, the height of fashion. The ingredients were kept in little ceremonial boxes, and consisted of dried pieces of betel palm nut and betel leaf folded into a cone shape and daubed with poon daeng, a paste of slaked lime, turmeric and water. Some users added shredded tobacco leaves. Farmers paddled boats loaded with betel leaves along the canals to the wholesale market at Talat Phlu, which grew as Bangkok grew, and eventually occupied a long stretch of the canal bank.

The betel-chewing habit continued long after Taksin’s time. It only ended during World War II., when the government of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram banned the growing and trading of betel to put a stop to the random spitting by chewers that soiled the city’s streets, lanes and buildings with red stains. Talat Phlu ceased trading betel, but the canny Chinese traders transformed it into a successful wet market. This has also become one of Thonburi’s most popular eating areas, famous for its traditional Teochew food that can be found in countless little family-owned restaurants and food stalls around the market and station. This reputation actually began many years ago, having gained considerable ground in the latter part of the nineteenth century when King Rama V visited Jeen Ree restaurant to sample its mee krob, a dish of crispy rice noodles stir-fried with pork, shrimp and egg. Located in a graceful old building next to the Talat Phlu Pier, and with a soothing interior of greys and blues, Jeen Ree is still there, serving the same dish. Presumably because of its royal fame this is one of the most expensive items on the menu, but at only 150 baht (less than five dollars) no one is going to complain, and it makes a satisfying lunch: mix the crispy noodles with pickled garlic, chives, bean sprouts and kaffir lime, and wash it down with Chinese tea. Elsewhere in this area, look for Teochew specialities such as chive dumplings, fish-ball soup and (my own favourite) duck noodles.

The King Taksin statue in the compound of Wat Intharam, where his ashes are interred.

Heading back towards Wong Wian Yai there is the choice of Thoet Thai Road, which runs parallel to the railway line, or the back-ways and alleys next to the canal. The latter are more picturesque, with only the occasional possibility of ending up in someone’s backyard. Go past the Baptist Church, past the fire station, past some old timber shophouses, over a small canal and past the pumping station, and then through Wat Klang Market, where the rooftops of Wat Mon can be seen glittering red, white and gold above the huddled roofs.

Wat Mon was built around the end of the Ayutthaya era by a community of Mons led by a soldier whose name is no longer known, but who may have been in charge of a small garrison here. Temple legend says that woodland on this bank provided cover for troops and that shallow water on the far bank drove boats close to the wooded shore, where if they were enemy boats they would be attacked. The settlement was known as Bung Ying Rua, which means, “to hide and shoot at boats”. The name was later corrupted to Bang Yi Rua, which means “Boat Village”, and as rural temples usually took their name from the locality, this was the early name of the temple.

During the Thonburi period, one of Taksin’s closest allies was a general named Phraya Pichai, who was also the governor of Uttaradit province, in the north of the country. Within this province is a village named Namphi, and nearby is mined an ore that goes into the making of a very tough steel traditionally used to forge swords for Siamese nobility. During one of the battles to drive the Burmese out of the country, Pichai confronted the enemy with a sword made from Namphi steel in his left hand and an ordinary sword in his right. The right-hand sword snapped during the fighting, but Pichai fought on two-handed with the Namphi sword and the broken blade. He won his battle, and entered into Thai history as Dap Hak, or “Broken Sword”, a heroic figure who is also revered as one of the great masters of Thai boxing. Pichai renovated and enlarged Wat Mon as a way of making merit for the men who had died during the battle.

Although Rama I made subsequent additions, Dap Hak’s chapel still remains, and carries his name. The artificial mountain near the temple wall dates from his time and is clad in seashells and rocks taken from the beach; there is a Buddha footprint on the top. Next to the temple gate is a small chapel containing an image of the Buddha lying flat on its back, symbolising the time immediately before cremation, the pose being known as Tawai Phra Ploeng. The image is about two-and-a-half metres long, almost filling the room, and is wrapped in a gold sheet, with an angel at the foot of the bier. Installed by Dap Hak, the image is the only one of its kind in Thailand. Pichai, 41 at his death, was cremated and his ashes interred here at Wat Mon, in the stupa. Devotees leave offerings at a small altar in front of a portrait, and next to the stupa is a topiary of Pichai in a fighting stance.

Longtail boats ply between communities alongside the Thonburi canals.

There were three temples at Bang Yi Rua that were so close they all bore the same name, being differentiated by the suffix Nai (inner), Klang (centre), and Nok (outer). While Phraya Pichai was renovating Wat Bang Yi Rua Nai, King Taksin found peace at Wat Bang Yi Rua Nok, where he would rest and meditate. He became fond of the temple and decided to adopt it as his own, carrying out extensive renovations and naming it as a royal temple. The temple became the most splendid of those along the canal bank, and an important place of worship for the noblemen and courtiers who were building homes alongside Klong Bangkok Yai. As befits Taksin’s Chinese ancestry, the architecture is a mix of Chinese and Thai. Inside the chapel, or wiharn, carved from a single piece of wood and flanked by four pillars and flower curtains, is the seat upon which the king would sit cross-legged in meditation. In front of the wiharn are two stupas, shaped like lotuses, and here is the final resting place of this great king. After Taksin’s death, his body was cremated and his ashes brought here and interred in the stupa on the right, the ashes of his queen being buried in the stupa on the left. Rama III bestowed the temple’s present name, Wat Intharam, when the temple was enlarged. The statue of the king upon his horse, sabre held high in his right hand, horse and king alike freckled with gold leaf, is a recent one, and a far more modest monument than the one at Wong Wian Yai. Sculpted life-size, it was commissioned soon after the end of World War II., when several miniature models were made by prospective sculptors and it was left to the public to decide which they liked best. Wat Intharam is today a place of pilgrimage for the Thais, especially those of Chinese descent, who in addition to coming here on the anniversary of Taksin’s coronation also pay homage at Chinese New Year. The third of the Bang Yi Rua temples, incidentally, still exists and is known as Wat Chantharam.

Wat Intharam’s compound backs directly onto the canal bank, where a frequent longtail boat service whisks visitors along Bangkok Yai and out to the Chao Phraya River. Next to the pier is a fine old two-storey wooden house whose front entrance uses a traditional Teochew method for securing the building against intruders. Erected inside the doorway are three or four wooden pillars. To get in or out, a person inside the house needs to remove a pillar. The pillars cannot be lifted from outside. As long as there is someone waiting at home, and as long as you don’t severely upset that person, it’s a pretty good system, as there is no key to be lost.