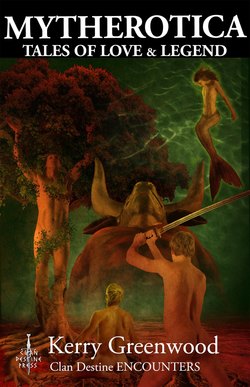

Читать книгу Mytherotica - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MERLIN

ОглавлениеFinally, a tree was returning his song.

Phillip Beckford, 2nd Earl of Doveton, had been playing his syrinx (an instrument of his own invention)all morning to the oaks, which were the oldest trees on his estate. He had been studying the nature of tunes sung by birds and seals, for three years. Plato had suggested that the universe began because of heavenly harmony and the Bible said that the morning stars sang together. Close research into Ancient Greek Orphic hymns had disclosed what the Orpheans thought were the notes which Orpheus used to charm man and beast alike, and so, they ought to work on trees. Perhaps they just took longer to react. These oaks were eight hundred years old. Three hundred years growing, three hundred years living, three hundred years dying, that’s what the country folk said about oaks. By the time that they replied, it might be a year later.

Perhaps he should seek out some saplings. They might be more responsive.

But at last, this very old and beautiful oak was singing in return. A modal song, the Myxolidian, sad and sweet. The tune resembled ‘Long A-Growing’. He stared into the trunk, playing the syrinx, a high, sweet piping, harmonising with the tree’s voice, and a figure began to emerge from the dark, wrinkled, iron hard bark. Man-sized, a man-face and head, long hair blown back, high nose, deep eye sockets, coming into being like a dark grey cloud picture. Phillip played, the tree sang, and gradually the man emerged, a hamadryad, a tree spirit.

Phillip longed for a male creature to love him, to stay close to him, to lie next to his heart. Legend said that the people of the trees were faithful, beautiful, and kind. His human lover had died young of a fever in Germany. He could never love anything mortal again. But he burned and wept in his solitude. He was virtuous, and cautious, enough not to consort with the dark powers. But he was so lonely in his great house, with servants and relatives and nothing at all to do, since he had lost the Queen’s Favour for not marrying the woman of her choice. Her Majesty had icily advised him that his presence was no longer acceptable in her court.

It would not have been right, to marry poor Bess. She was a kind girl and deserved a good husband.

But the tree was singing and the spirit was almost separate from it, gaining colour as his flesh struck the air. He was beautiful, pale skin, waist-length, oak-bark coloured hair, eyes as green as new oak leaves. But his mouth was as red as a holly berry and he wreathed his new arms around Phillip’s shoulders and kissed him, breathing his first breath from his lips.

Phillip sobbed, kissed, and slumped to the ground. The tree man followed, kissing, and then somehow Phillip was naked, too, and they were lying together on a previously unsuspected purpl cloak, and Phillip and the tree man were making love so sweetly and generously that they cried out together and lay snuggled into each other’s embrace.

Then the tree fell silent. The tree man lay back, chuckling, staring into Phillip’s eyes, and stroked his cheek with one smooth forefinger. He was young, perhaps, his body was muscular and unscarred, his face unwrinkled. But there was a depth of age and wisdom in his eyes which made Phillip almost afraid.

‘You freed me,’ said the tree man. His voice was deep and rich and strongly accented. ‘What is your name, my love?’

‘Phillip Beckford,’ he stammered. ‘Do hamadryads have names?’

‘Not generally,’ replied the tree man. ‘I, on the other hand, am not a dryad, but a prisoner, and you have freed me. A very long time ago a wicked woman sealed me into this tree, and it and I have grown old together. When I was a man I was called Myrddin Ambrosianus.’

‘The wizard Merlin?’

Merlin raised himself a little on one elbow and bowed. ‘The very same.’

‘They said that Nimue sealed you in a cave because you threatened her virtue,’ said Phillip.

Merlin reached across, slid a hand around the back of Phillip’s neck, and drew his head towards him. There he kissed the young man’s mouth until he was close to swooning, as bees swoon in midsummer in the clover fields, so sweet, so sweet!

‘Do you think I am a threat to any woman’s virtue?’ he laughed. ‘Yours, perhaps, but it was your longing that brought me forth, and your tune. No, Nimue wanted power. And with me gone, she got it. And, I have no doubt, misused it and brought ruin on the kingdom and the death of the King.’

‘Yes,’ said Phillip.

‘Thought so,’ grumbled the wizard, pillowing his head on Phillips naked chest. ‘A long time ago?’

‘More than a thousand years,’ Phillip told him, stroking the silky hair back from the sorrowful face. Merlin sighed.

‘How did my poor Artos die?’

‘His bastard son Mordred killed him – or so they say,’ replied Phillip. ‘But he ordered his knight to throw Excalibur into the water, then three ladies came and took him away in a boat, to the Isle of Avilion, to wait for a change of days.’

‘Ah, yes, the prophecy,’ murmured Merlin. ‘I made it myself. Rex Quondam et Rex Futurus. The Once and Future King. So, Artos will be at rest, then. So many years gone past. Lie down with me again, my Pip,’ he said gently. ‘It has been so long since anyone loved me.’

‘Yes,’ breathed Phillip, as wise hands slid and touched. Merlin tasted sweet, like oak flowers, and the scent of his skin was mossy and woody, deep and musky. Phillip sank into the magician’s embrace, already bewitched, and almost weeping with delight.

Phillip woke and turned drowsily in the young man’s arms. He had been half afraid that Merlin would have vanished, but he was still there, lying on the purple cloak in the warm dappled shade under his parent oak.

‘I listened, you know,’ said Merlin in his woody, tenor voice. ‘All the time I was enclosed. In the winter I and the tree slept, we woke alert in the spring, enjoyed the summer, and fell asleep again in autumn. And although I was captive I was not in pain: I had no body but the tree’s. Mostly I drowsed. But I listened to humans, I heard men making love under my boughs.’

‘What did you hear?’ asked Phillip, kissing the chest on which he was pillowing his cheek.

‘I heard the Saxons coax ‘hunig’ to their lovers, then the Normans. They had more words. ‘Mon brave, mon ame, mon amour, mon cher, mon p’tit chou’, and then came the English you speak, my honey, my heart, my dearling, myn lyking. I would say them to myself, thinking that if ever I was released and found a man to love, I would say them all. I would never stop saying them.’

‘Sweeting,’ said Phillip. ‘Will you stay with me?’

‘Oh, yes,’ replied Merlin, ‘if you want me.’

‘Never doubt that,’ said Phillip. He stretched. ‘Suddenly I am very hungry,’ he added. ‘Will you come into the castle with me? I would show you your new home. And perhapsI can give you some clothes?’

Merlin laughed, sat up, then stood with his hand against the tree. He made a small gesture, and was clothed in his long white robe and purple cloak. He watched as Phillip re-assembled his own wardrobe. Stockings, breechclout, trunk hose, codpiece, belt, shirt and doublet.

‘What are those?’ he asked.

‘Trunk hose,’ said Phillip.

‘Your clothes are strange and interesting,’ commented the wizard. ‘I shall have to examine them more closely before I can produce copies. But this will do for now?’ he asked.

‘Certainly,’ said Phillip. ‘You look very beautiful. Take my hand, or I shall believe that I imagined you.’

Merlin took his hand. It was a definite clasp, fingers and palm. Phillip’s imagination was good, but it was not that good.

At a late dinner, Merlin tasted new fruits and complimented the cooks and drank a little red wine of Portugal, well diluted with spring water. Phillip had never had such an interesting guest. He found himself telling Merlin about the court of the Great Queen Elizabeth, by Grace of God, Queen of the English. Merlin chuckled.

‘Women,’ he commented, ‘like men, love power. This one seems to be a better bet than her father or her siblings. At least she loves the country. Countries know if they are loved – particularly England. It is no common earth, the Island of Britain. She knows her friends.’

‘Was Artos her friend?’ asked Phillip.

‘He was,’ said Merlin.

‘Merlin, how much magic can you do?’ asked Phillip.

‘As much as I ever could, my heart,’ he replied. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘Don’t you want to bring your Artos back?’ asked Phillip, biting his lip on a surge of quite-unbecoming jealousy. Merlin took his hand and kissed it.

‘Artos is gone. He was of his time and he cannot be summoned out of it. But you are here, and so am I. And that is where we should be.’

‘So it is,’ said Phillip, smiling, and poured more wine.

Three hours later, when it was fully dark, the lookout’s boy rushed into the hall, fell at Phillip’s feet, and gasped ‘Master, Master, the beacons are lit! The Spanish fleet is sailing!’

‘Is our beacon afire?’ demanded Phillip.

‘Yes, Master,’ panted the boy. Phillip gave the boy his wine cup.

‘Good. Drink this, now, and sit still until you get your breath back. Will you come with me?’ he asked Merlin.

‘Where else should I be?’ replied the wizard. He followed Phillip as he strode through the hall, calling, ‘turn out the guard! Tom, my armour! My dear, can I get you a weapon?’

‘I need none,’ replied Merlin. ‘But I will meet you outside.’

Merlin took a sharp knife, a draught of wine and a napkin and went into the darkness, moving surely on his hard bare feet. The hall bustled with noise and life. Phillip saw his lover walk out of it into the silent darkness and almost clawed after him.

Then the multifarious tasks claimed him for an hour. When Phillip walked out of the great house to mount his horse, Coalblack, he found the wizard standing, waiting for him. He was still clad in white and purple, but he had a bloodstained napkin trussed around his left arm. And in his hand he held a long, strong oak staff.

‘The tree required a sacrifice,’ said the wizard. ‘It is nothing. Where is your enemy?’

‘Mount and ride,’ ordered Phillip. The wizard sat as easily in a saddle as a chair.

Two hours later, they stood on the edge of the cliff and looked at the huge array of ships sailing. Phillip had never seen so many vessels. The full moon picked steel and silver from their decks and masts.

‘They do not mean to go ashore here,’ said Phillip’s armour bearer, Tom. ‘That’s good, isn’t it, Master?’

‘And if they invade, my boy, what place will be safe from the Inquisition? They will light the fires of Smithfield all over England. And the ocean’s as flat as a plate! Oh, for a witch who can whistle a wind!’

‘Why should you need a witch?’ asked Merlin in a low, amused voice. ‘I was a tree for many winters and know winds as only a tree can. And their ships,’ he said, lifting the staff, ‘are made of wood. Tell your men to fall back, myn lyking, get the horses back from the edge. And you go back, as well.’

‘No,’ said Phillip. He dismounted, gave the horses to Tom, and ordered the guard back into the small village in the valley, where they could shelter from any storm. ‘I just found you, I’m not leaving you.’

‘My love,’ said Merlin, fondly. ‘You have your syrinx?’

‘I have,’ said Phillip.

‘Then we shall play such a song as the winds will answer,’ said Merlin, and raised the staff, beginning to sing in a low, rumbling monotone. Phillip followed the notes, shrill and high, and, summoned, a wind began to rise.

It rose and roared, and over it the guard heard, piercing, the notes of the syrinx, and the low notes under it, as the gale picked up and the waves responded. Into the song was woven the grinding of sand on shoals and the crashing of the flood on cliffs and rocks, and even from the village they heard the screaming of sailors and the smashing of ships. There would be a fine harvest of broken keels tomorrow, for the gleaners to feed their fires.

Sometime later – the moon had gone down – the guard ventured up onto the cliff. They found their master and his strange guest, locked in each other’s arms, lying soaking and freezing on the rocks. They carried them home in the pelting rain.

Phillip woke, warm and dry and cosy, in his own bed. At first he wondered if he had been fevered and dreamed, but then he sneezed and brushed a tress of oak-bark hair from across his nose. Merlin was there, deep asleep.

Someone had brought them home, dried and put them to bed. The fire in the room was just burning down. It was late afternoon.

‘Master?’ asked Tom, who was bringing in more logs.

‘Tom, my boy, how goes the day?’ whispered Phillip.

‘The Armada is mostly wrecked, Master,’ Tom told him. ‘It was that God-given storm, Master, that’s what we are all saying. That you prayed to the Lord and our Heavenly Father, He sent the storm. And Saint George. Some people are saying they saw him, marching over the waves.’

‘That’s a good thing for you to say, Tom,’ said Phillip.

He looked around the room. Merlin’s staff and his syrinx lay shattered on a purple cloak. That did not matter. Both could be replaced. And Merlin was lying beside him, sleeping, his leaf-green eyes closed; a lover who would not leave and would not die. That oak tree still had a good hundred years left.

It was probably just a coincidence (though there has never been a better-informed monarch than Elizabeth Regina) that when My Lord Phillip of Doveton was awarded a Royal Mark of Favour for his readiness and defence during the Great Armada, it was a medallion with Saint George on the face, and, on the obverse, an oak tree.