Читать книгу Mytherotica - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

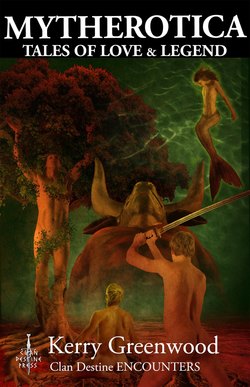

RUMPLESTILTSKIN

ОглавлениеPaladin sat in his chair. He had no choice, being tied to it with regrettably competent knots. His hands were free, he had a spindle in one and a large heap of straw at his side. They hadn’t taken his sharp knife which hung from his belt, but even if he could get free, he was a very long way from the ground in this tower and had always been deathly afraid of heights.

It was such a pity that his father was a fool. As a miller’s third son, Paladin had been allowed to please himself as to profession. He had perfected a way of spinning flax into good, strong thread. This involved the use of a glue made from the retted reeds themselves, which when slicked along the worker’s fingers allowed the threads to combine seamlessly. He could spin two ells of linen thread without a lump or knot.

So his idiot father had boasted of him to the king, and the king had decided that if he could spin reeds into linen, he could spin straw into gold.

And if he didn’t manage it, he would be dead in the morning. And if he ran away, his father would take his place.

It was also a pity that the king was a fool.

There was a scrabbling at the window, and two paws appeared on the sill. A second later a battered orange tom cat was sitting on the floor in front of Paladin, having a brief wash to smooth his ruffled fur before engaging in conversation.

‘Your father is such a fool,’ said the cat.

‘I know,’ sighed Paladin. ‘And the king. Any suggestions?’

‘You could get out and I could take you down the wall,’ said the cat, flicking an ear. ‘But that wouldn’t save your father.’

‘No,’ sighed Paladin. He put down the spindle and brushed his brown hair off his face. ‘Much as I blame him, he is my father.’

‘I could ask for some supernatural help,’ suggested the cat diffidently. ‘But it comes with a price.’

‘What sort of price?’ asked Paladin. ‘If it’s organs or body parts, I might as well jump from the tower.’

‘No, no, probably just your jewellery,’ said the cat. ‘Make up your mind, I’m just borrowing this cat, and he has other things to do - kittens to father, male cats to fight, you know how it is.’

‘Oh, my dearest Tuatha, I wish you were here! I wish I could touch you, kiss you, if this is to be the end.’

‘Paladin, my lamb, you know you can’t touch me,’ soothed the cat. ‘Not until you - decide. And I’m not taking you out of human to save you; that never works, they all end up wishing they could die and hating their Tuatha. So, shall I call on a gnome?’

‘Call,’ decided Paladin. Making a private vow that if he did get out of this, he would find the Fae and fling himself at his immortal feet and beg for an embrace.

The cat jumped into Paladin’s lap, ran a purring nose along his jaw, bit his earlobe, then jumped down and leaped out the window.

There was a flash, a puff of peppery smoke, and a small cross man stood before him. He was wearing a red gown and had his slippers on the wrong feet. His pink nightcap was crooked.

‘What?’ he growled. He had obviously woken up on the wrong side of his mushroom.

‘Spin straw into gold,’ said Paladin, indicating the heap.

‘That king,’ said the small man, with a grin, ‘is such a fool. All right, standard fee.’

‘What’s the standard fee?’ asked Paladin warily.

‘Your ring,’ replied the gnome. He leaned forward and licked the gold ring on Paladin’s finger, showing long pointed teeth, and suddenly he wasn’t at all comic. Paladin wrestled the damp ring off and dropped it into the gnome’s hand. He really didn’t want it any more.

‘Right, out of the way,’ said the gnome. He snapped the ropes with thumb and forefinger, shoved Paladin out of the chair, and he sat amazed on the cold stone floor as there was a blur of motion, the spindle rocked, the wheel whirred, and the pile of straw diminished as the spool of gold thread grew. It couldn’t have taken more than ten minutes.

‘Simple,’ said the gnome. He approached Paladin and thrust his face close to the young man’s neck. ‘You smell delicious,’ he said.

‘Thanks!’ squeaked Paladin. There was another flash and more of the peppery smoke, and the gnome was gone.

Paladin curled up in his cloak and slept uneasily until morning. He had a feeling he wasn’t out of this situation yet.

He was, of course, right. Presented with a spool of undeniable gold thread, the king locked him in another tower, with a much bigger heap of straw. This time he was not bound, and even provided with supper and wine. He had not been allowed to speak to his father, who was - horribly - boasting of his son’s amazing skills even now, when the said son was running out of bijoux to bribe the gnome.

‘Again?’ sighed the cat.

‘Again?’ asked the gnome as Paladin sneezed in the peppery smoke. ‘That king is a greedy moron. There’s a limit to how much straw even I can spin. Luckily he hasn’t reached it yet. Usual fee?’

‘Which is?’ asked Paladin. The gnome was making his skin crawl by the way it was grinning at him.

‘That necklace. It’s old - I like old - let me taste it.’

Paladin ripped it off his neck and the gnome looked disappointed. He put the necklace into his mouth, nevertheless.

And then the wheel whirred into motion, the spindle rocked, the pile of straw diminished, and ells and ells of gold thread spooled off into Paladin’s hands.

‘By tomorrow,’ said the gnome very quietly, ‘the king will demand that you spin more straw, you won’t have anything to trade.’

‘And then your fee would be?’

‘To have you,’ said the gnome. ‘To taste you all over. And to bite three bites out of your flesh - wherever I choose.’

‘Well, I’ll just have to die then,’ said Paladin. He could imagine where those three bites of flesh would come from. He had no fancy to bleed to death, castrated, on this tower floor. He could always jump. That wouldn’t take anything like as long.

‘I’ll make you a wager,’ said the gnome.

So close, it reeked of decaying leaves, stagnant water, and blood. Paladin tried not to breathe.

‘And that would be?’ Paladin was pleased that his voice sounded almost steady.

‘You have three tries,’ said the gnome. ‘You have to guess my name. Accept?’

‘All right,’ said Paladin. If he stood directly in the window embrasure, he would be able to leap, if he guessed wrongly, before the creature could lay a fang on him.

The peppery smoke made him sneeze again. Sneezing, he called on the Tuatha. Soon an owl landed on the sill. It mantled, ordering its wings, then hopped down onto the arm of the chair.

‘Too far for a cat to climb, this tower’s higher,’ it remarked.

‘Tuatha, what is that gnome’s name?’ demanded Paladin.

‘I don’t know,’ said the owl. ‘They don’t usually have names. Why? Is it important?’

‘Very,’ said Paladin, and explained.

‘And I can’t help you,’ said the owl sorrowfully.

‘Why not?’

‘Magical bargain, my own darling. I am forbidden to find out for you. But I can give you a hint,’ he said. The owl preened briefly.

‘Yes, give me the hint. And if I get out of this, you are turning me, no argument, all right?’ said Paladin, tearing at his hair.

‘Yes, oh, yes, my love,’ soothed the owl. ‘You can do this. Your mother gave you something when you were born, you’ve never used it. Not an object. A talent. Stand at the window and look. Look deep.’

‘Is that all?’ cried Paladin, dismayed.

The owl flew up to his shoulder and ran its beak along his neck, fluttering its soft feathers against his cheek.

‘Soon,’ it said, ‘you will lie on my breast, and nothing will part us again.’

Then it arrowed straight out of the window.

Paladin drank the rest of the wine. And called for more.

It was dark outside. Look deep, he thought. He ate the rest of the ragout de lapin au fines herbes and stood at the window opening. He leaned his hands on the sill. Too uncomfortable. He dragged his chair over to the space, sat down and wrapped his cloak around him.

Then he looked. The stars were out, flowering as silver as his Tuatha’s eyes. He could see the vague shapes of trees, hear the murmur of the forest. He could hear men carousing in the great hall and a spill of torchlight as the door was opened to let the guests depart. Someone was playing a small pipe, very tunefully, in the kitchen, where they must have finished the washing up and be eating their own supper. He strained his eyes, but it was nearly too dark to see. His head hurt.

Tears pricked, and he wiped them away. He sipped some water and leaned forward again. A bat flitted past, squeaking ‘look deep!’ almost too high for him to hear.

His mother - she had died when he was only five. He didn’t recall her saying anything about looking, deeply or shallowly. He missed her suddenly. The only woman in his father’s house who wasn’t a servant was his sister Estelle, a fierce red headed woman, shortly to be married. Estelle would want him to try. He could practically feel her work-worn hand clipping lightly at his ear, saying ‘Try again!’

So he tried again, pressing both hands on his temples, forcing his sight beyond vision, and suddenly he could see deeply. And a hot point of light directed his gaze to a small fire, around which someone was dancing. Someone squat, with short legs and a pink cap.

‘I’ve got him!’ cried the dancer. ‘I’ve got him! He can’t ask his Fae for help, and no one knows my name is Rumplestiltskin! And tomorrow I shall eat him all up! His blood will taste like wine, like wine!’

Paladin shuddered, wrapped his cloak tighter, left the window, and wrote Rumplestiltskin on his forearm with pen and ink.

Then he savoured the remaining wine, and fell asleep.

The next day the king sent men to have him moved to a taller tower with even more hay. The soldiers were complaining about carrying bales of the stuff up so many stairs. Everyone was out of breath.

‘It’s all right for you,’ growled one to Paladin. ‘All you have to do is spin the straw. And the king has to let you go tomorrow.’

‘Why?’ asked the young man. The guards chuckled.

‘Mistress Estelle Miller, that’s why. She turned up with all your brothers and the townspeople and swore she’d burn down the mill if he didn’t release you tomorrow. And that’s the only mill for miles.’

‘Strong minded woman, that Estelle Miller,’ agreed his fellow guard.

‘Sent her father home with a flea in his ear, too,’ said the first guard, wincing slightly.

‘Here you are,’ said the guard, showing Paladin into a small tower room absolutely carpeted with straw. ‘Try to live through the night,’ said the guard, and patted Paladin on the shoulder. ‘Here’s your supper, and we brought you a couple of extra bottles of wine. The good stuff. Good luck, son,’ said the guard, and they tramped down the stairs again.

A mouse ran onto his foot as he sat down on the spinning chair. It put both little paws on his bare ankle.

‘Tuatha?’ asked Paladin.

‘Of course,’ squeaked the mouse.

‘When this ends, come and get me? I don’t want to go down all those stairs again,’ said Paladin. The mouse giggled.

‘You’ve got it, then?’

‘I think so,’ said Paladin.

The mouse vanished with a whisk of tail, and the peppery smoke announced the arrival of the gnome. He surveyed the quantity of straw and spat

‘Did I mention that the king is a greedy moron?’

‘You did,’ replied Paladin, sneezing.

‘This time our fee is different,’ said the gnome, approaching Paladin and breathing into his face. Stale water and old iron.

‘Yes,’ said Paladin. ‘Three guesses. Tell me, are you a Trevor?’

‘No,’ said the gnome.

‘Funny - it’s Old French for trés vor, very hungry, and you’re cruel, bloodthirsty, and ultimately unfair. Unkind. And really, really ugly. You absolutely look like a Trevor.’

‘I said, no,’ replied the gnome, leaning both sharp elbows on his knee.

‘All right, if you insist.’ The gnome showed all its teeth and started to unlace Paladin’s shirt. He shivered under the unclean touch.

‘Well then, what about John? Nice common name, everyone’s got a John or a Jean or an Ian or an Evan or an Ivan or ...’

‘Wrong,’ gloated the gnome. It started on the side lacings of Paladin’s breeches.

‘Then I expect you must be,’ he consulted his forearm, ‘Rumplestiltskin. Sorry,’ he added, as the creature was forced back from him as by a sharp push. It screamed ‘Yes!’ as it was shoved to the wheel and the straw and started spinning so fast the wheel was a blur.

‘Tuatha,’ said Paladin firmly, standing up. ‘Come to me now. I am sure. I won’t stay in a world where a king can confine me and compel me to make bargains with monsters for my father’s life. I want you, I love you, I need you. I have called you thrice. Come.’

There was a shining silver mist laid over the tiny room, blanketing the swearing gnome and the spinning wheel. A voice called from the window, ‘Come,’ and Paladin, taking a bottle of wine, walked to the window, off the sill and along a silver pathway into the embrace of a silver man, hanging in mid air.

‘I am yours,’ said Paladin.

‘I am yours,’ said Tuatha. ‘We are together. Come, we must tell your sister what happened. And give her the wine. Then -’

‘Then?’ asked Paladin, nestling into the warmth and spicy, wild scent of the Fae.

‘Then you come with me,’ said the Fae. ‘And I will give you wild water to drink, headier than any wine, wild songs to sing, wild paths to walk, and my love forever.’

‘Oh, my love,’ sighed Paladin.

The king was quite cross when all his gold thread was found, on inspection in the morning, to have turned into string. Dirty string. And Paladin was nowhere to be found.