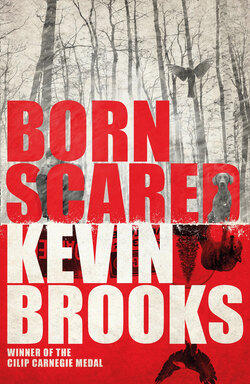

Читать книгу Born Scared - Kevin Brooks - Страница 14

10 A DEAD BLACK LINE

ОглавлениеME: Do you think I’m mad?

DOC: Do you?

ME: I don’t know . . . sometimes, maybe. I’m definitely not normal, am I?

DOC: None of us are normal. We all have things wrong with us. It’s just that some of those things have a much bigger effect on our lives than others.

ME: Do you think something could have gone wrong in my head when I was a baby?

DOC: Do you mean when your heart stopped?

ME: Yeah. Maybe my brain stopped too, or it got damaged or something.

DOC: Well, that can happen, yes. If you’re starved of oxygen at birth it can lead to irreversible brain damage. But in all the instances I’ve ever come across, the oxygen supply has been stopped for at least two or three minutes, usually quite a bit longer. But that wasn’t the case with you, Elliot. Your heart stopped beating for less than a minute.

ME: Yeah, but what if –?

DOC: There’s absolutely nothing wrong with your mind, Elliot. Trust me. If you’d suffered any brain damage I’d know.

ME: So are you saying it’s perfectly all right for me to be terrified of everything?

DOC: No, of course not.

ME: So there is something wrong with my brain then.

Sometimes I have no sense of the present. All I can feel is a sense of the past and a sense of the future – the ‘then’ and the ‘when’. I can look back and remember things – things that happened, things that I did – and I can look forward to things that haven’t happened yet. I can imagine things happening in the future – the next half hour, the next day, next Monday afternoon, next year. I can do all that. But the present . . . the present seems to pass me by. I can’t get hold of it. It’s like a shapeless and senseless void that moves, like a cursor, between the past and the future. A dead black line, forever moving, forever being . . . but never actually there.

ME: I know you think I’m weird.

DOC: What makes you say that?

ME: I heard you talking to Mum once. You told her it was really weird how sometimes I sound really grown up, almost like an adult, but other times I seem almost babyish.

DOC: I didn’t say it was ‘really weird’, I just said I’d noticed it, that’s all. And I didn’t say ‘babyish’ either. All I said was that sometimes the way you talk makes you sound older than you are, and sometimes you come across as being younger than you are. I didn’t say it was ‘weird’. And I wouldn’t use that word anyway.

ME: What word would you use?

DOC: I don’t know . . . ‘different’, perhaps.

‘Unusual’. There’s nothing wrong with being unusual.

I’ve never met my father. According to Mum, she met him at a party, they spent the night together, and that was that. They never saw each other again.

‘It was all perfectly amiable,’ she told me once. ‘He was a lovely man, and we had a very nice time together. But neither of us wanted to take it any further, and we were both quite happy to go our separate ways.’

‘What was his name?’ I asked her.

‘Martyn.’

‘Martyn what?’

‘I honestly don’t know. He introduced himself as Martyn, and I told him I was Grace, and that’s all we needed to know.’

Even if she had known his surname, she still wouldn’t have made any effort to contact him when she found out she was pregnant.

‘It would only have complicated things,’ she explained. ‘And besides, apart from his name, the only other thing I knew about Martyn was that he lived in Los Angeles and he was a writer, but he didn’t write under his real name. So I couldn’t have tracked him down even if I’d wanted to, which I didn’t.’

I don’t miss having a father – you can’t miss what you’ve never had, can you? – and on the rare occasions when I do wonder what it would be like to have a dad, the mere thought of it makes me shudder. A man living in my house? A monkem? A man I’d have to share Mum with . . .?

No.

I wouldn’t like that one bit.

DOC: We might not know the precise cause of your problem, Elliot, but we know how it affects you, and it might be possible to lessen those effects to some degree.

ME: How?

DOC: There are anti-anxiety medications that might help. They’re obviously not intended for treating the level of fear that afflicts you, and normally I’d never even consider this type of medication for a child, but you’re a far from normal case, Elliot.

ME: Thanks a lot.

The Doc looks totally different when he smiles, which isn’t very often. But when he does smile, it lightens his face, makes him look younger. It lifts his mask of sombre gravity and reveals a twinkle of the child in him.

DOC: Anyway, I’ve talked to your mum about it, and although she hates the idea of putting you on medication as much as I do, she agrees that it’s worth giving it a go. But only if you want to try it.

ME: Will the drugs stop me being afraid?

DOC: No, but they might lessen the severity of your fears.

ME: So I’ll still be scared of things, but not so much.

DOC: Possibly, yes. It’s also possible that medication won’t help you at all. In fact, it could actually make you feel worse. But the only way to find out is by trying it. You also need to bear in mind that there are dozens of different types of anti-anxiety medication, and it could easily take months, or even years, to find out which of them – if any – is best for you. Now I know this is a lot to think about, but at the moment that’s all I want you to do – just think about it, okay? There’s no rush, you can take as much time as you want. And if there’s anything you’re not sure about, anything you want to ask, just let me know, okay?

ME: Yeah.

DOC: We can do this, Elliot. We can do everything possible to make you better. But we have to do it together. We have to do it between the three of us – you, your mum, and me.

And Ellamay, I added silently.

Thank you, she said.

You’re welcome.